13 Explaining Key Features in Outdoor Therapy

Virginie Gargano; Justine Pellerin; and Roxanne Létourneau

Editors’ note: This chapter focuses on the more researched field of outdoor learning known as outdoor therapy (OT) that includes nature therapy, adventure therapy, wilderness therapy, and other modalities.

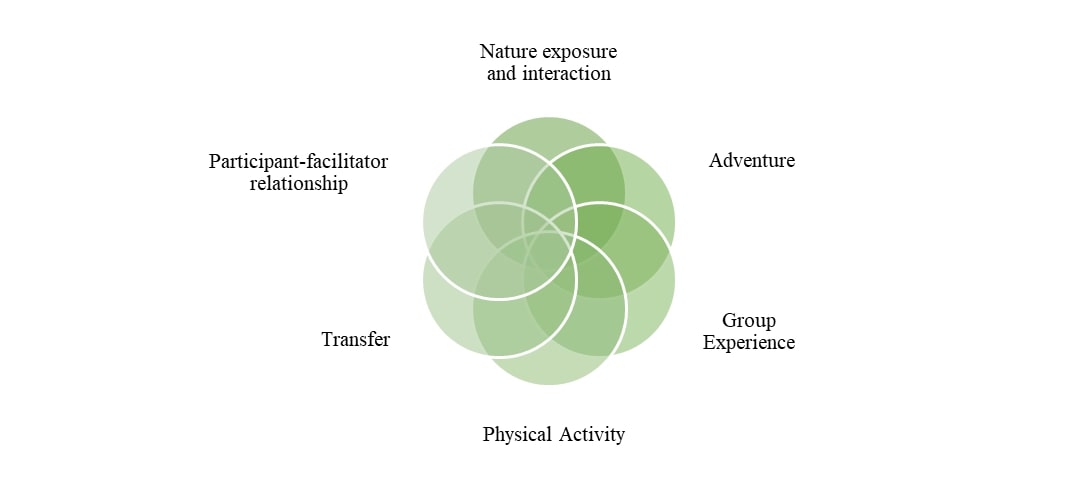

Over the last fifty years, outdoor therapies (OTs) have been the subject of extensive research, which has revealed their positive influence on multiple facets of general well-being (e.g., self esteem, self-efficacy, leadership), as well as social, academic, and family functioning (Gargano, 2022; Harper & Dobud, 2021). Only recently, researchers have begun investigating the factors contributing to these effects. Today, nature exposure, adventure, group experience, physical activity, transfer, and the relationship between facilitators and the participants are recognized for their importance in OTs (Priest, 2023; Russell et al., 2017; Sheffield & Lumber, 2019; Van den Berg et al., 2019). However, research is limited on how to implement these features within OT programs, which diminishes their application efficacy in existing OT practice.

This chapter aims to address this situation by discussing the definition of OTs, identifying the key features, and considering the implementation of each. The impact of key element and their sub-dimensions are further examined and theoretically explained for their contributions to beneficial outcomes. The elements required to operationalize each feature and the challenges associated with incorporating these into professional practice are highlighted. Finally, a reflection tool is presented to assist facilitators in planning OT programs.

Various synonyms have been offered to describe programs taking place in an OT context. For example, these include “wilderness therapy” (Davis-Berman & Berman, 1994), “bush adventure therapy” (Pryor et al., 2005), or “adventure therapy” (Gass et al., 2020). This chapter uses the term outdoor therapies (OTs) to maintain a broad perspective of nature and adventure as an intervention modality, as proposed by Harper and Dobud (2021). This term covers a range of psychosocial practices conducted in natural settings, with or without adventure, aimed at promoting overall health and conducted from an egalitarian perspective emphasizing equality between humans and nature.

Key Features

Since 2000, the lack of scientific understanding about the processes at work in OTs, known as the “black box phenomenon,” has sparked the interest of various groups of authors (Fernee et al., 2019; Gargano, 2020; McKenzie, 2000; Newman et al., 2023; Norton et al., 2014; Russell et al., 2017). Different labels were attached to important program elements, described as “key components” (Norton, 2010), “key factors” (Norton et al., 2014), “key features” (Gargano, 2020), “process factors” (Russell et al., 2017), and “facilitative practices” (Newman et al., 2023). The term “key-features” will be used here to encompass nature exposure, adventure, group experience, physical activity, transfer, and the participant-facilitator relationship as listed in Figure 1.

Before examining the impact of each key element in OTs, it is important to consider two steps in program planning: determining the purpose to be achieved and recognizing the characteristics of the participants. These steps will have a direct influence on the implementation of key features.

Regarding the targeted objectives, these must be broken down into a single purpose (Turcotte & Lindsay, 2019), since this will guide the intervention process, both in design and during delivery. As for participant characteristics, these considerations are central to program success. Learning about their physical, psychological, emotional, and social abilities, as well as their strengths and needs, are critical to establishing guidelines to select group members and define inclusion and exclusion criteria. Although these considerations come from the literature on group intervention (Turcotte & Lindsay, 2019), each is just as relevant with respect to OTs (Gargano, 2021).

Nature

Several definitions for nature have been developed in the literature. In this chapter, nature refers to all elements and phenomena originating from the land, water, or biodiversity, including fire, weather, and geology, influenced by humans or not, from a potted plant to untouched wilderness, as suggested by Bratman and colleagues (2012).

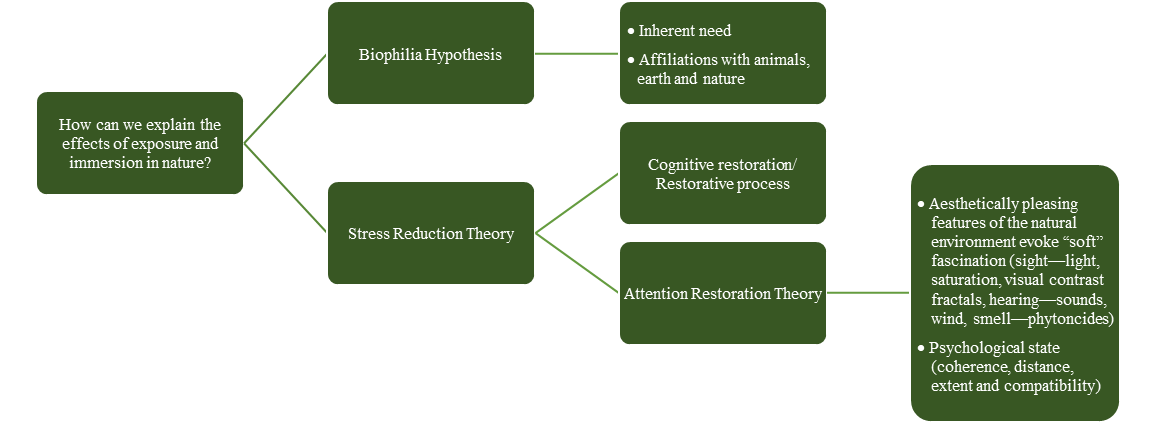

Whether resulting from human intervention or not, natural environments have the potential to promote and support overall health (Hartig et al., 2014). Different hypotheses and theories have been proposed to explain how these effects occur, including the Biophilia Hypothesis, Stress Reduction Theory, and Attention Restoration Theory. The sensory experience is an important piece of nature immersion and can be added to all of these theories, since the use of human senses transversally extends across various interpretations of nature as in Figure 2.

Biophilia is defined by the innate human instinct to connect with everything related to nature (e.g., animals, Earth). Used for the first time in 1964 by the psychoanalyst Fromm (1964), this term was developed in opposition to the term “necrophilia” or the “love of life in contrast to love of death. [It] represents a total orientation, an entire way of being. It is manifested in a person’s bodily processes, in his emotions, in his thoughts, in his gestures” (p. 45).

In the 80s, sociobiologist Wilson (1984) put forward the biophilia hypothesis, which states the belief that humans are genetically predisposed to be attracted to nature and “the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes” (Wilson, 1984, p. 1). To date, some studies have suggested that a lack of connection with nature induced by modern lifestyles leads to a sense of disconnection in humans, resulting in a stress response (Darcy et al., 2019). Despite the abundant literature on this concept, the hypothesis has not yet been validated and remains the subject of much criticism (Gaekwad et al., 2022; Joye & De Block, 2011; Scopelliti et al., 2018). While research has yet to support the biophilia hypothesis, the idea does carry considerable public interest and highlights the benefits of nature on human health.

Stress Reduction Theory states that in the absence of a genuine threat (e.g., animal attack, storm), nature promotes the reduction of stress and favors cognitive restoration (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Rogerson et al., 2019; Ulrich, 1981). This is defined as: “The process of renewing, recovering, or reestablishing physical, psychological, and social resources or capabilities diminished in ongoing efforts to meet adaptive demands” (Hartig, 2004, p. 273).

Attention Restoration Theory suggests that the ability to direct voluntary awareness decreases with use, particularly because it requires cognitive effort to ignore distractions. Finding oneself in a situation that does not require voluntary attention would then promote the recovery of cognitive resources (Staats, 2012). To achieve this, different parameters come into play (Calogiuri et al., 2019; Kaplan, 1995; Menardo et al., 2019; Schertz & Berman, 2019), including the state of soft fascination. According to Kaplan & Kaplan (1989), this state is favored by the natural environment, as it requires minimal cognitive resources, particularly when it focuses on the natural elements present in the environment. Three psychological components influence this state: the feeling of being in the right place, the degree of coherence with the environment, and the distance from the obligations of daily life (Calogiuri et al., 2019).

Sensory Experience

In the literature, the term “kinesthetic experience,” the conscious perception of the body’s position and movements in space (Larousse, 2022), is commonly used to describe the sensory experience related to OTs. However, a more accurate terminology is “sensory experience” to represent all the senses involved in OTs and not just the body. Closely linked to the theory of soft fascination, sensory experience, the mobilization of the senses such as sight, hearing, smell, touch, taste, also plays a role when experiencing nature and is thought to promote cognitive restoration and general well-being (Shin et al., 2022).

With respect to eyesight: the high degree of brightness, contrast, light saturation points (Beckmann et al., 2019), the luminous colors found in nature, such as green (Lohr, 2010). Fractals or complex shapes found naturally in clouds, waves, leaves, or flowers, favor these benefits (Taylor, 2021; Zosimov & Lyamshev, 1995). According to Seuront (2010, p. 1): “A fractal set tends to fill the whole space in which it is embedded and has a highly irregular structure, while it possesses a certain degree of self-similarity [and] appears to be the union of many ever-smaller copies of itself.”

As for hearing, the singing of birds, the wind, the sound of water flowing down a river are just a few examples that promote states of calm and general well-being when in contact with nature (Ratcliffe, 2021; Van Hedger et al., 2019). On the olfactory level, volatile organic derivatives emanating from many plant species, called phytoncides, are also considered to positively influence physiological and psychological health (Li et al., 2006; Rogerson et al., 2019).

To summarize, despite studies inventorying the relationships between Stress Reduction Theory, Attention Restoration Theory, and the involvement of the senses in OT outcomes, recent work emphasizes methodological limitations associated with these. Therefore, a further deepening of understanding and a better comprehension of cognitive phenomena that occur during human contact with nature is necessary (Menardo et al., 2019; Ohly et al., 2016; Schertz & Berman, 2019).

The level of immersion in nature is certainly one of the most complex parameters for facilitators to configure among other reasons because this depends on the personal conceptions and previous experiences of each individual. Whether deliberate or circumstantial, experiences in nature can be tainted by people’s life trajectories and their sociocultural, economic, and geographic contexts (Bratman et al., 2019; Keniger et al., 2013). In addition, considering the personal characteristics of the participants, certain parameters inherent to OTs can guide the facilitator’s choices, such as quality of contact, duration, frequency, and type of environment, such as being in the forest or on the open ocean (Shanahan et al., 2015).

Adventure

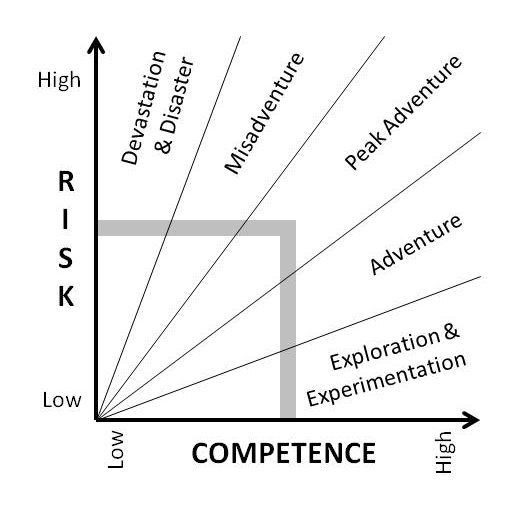

An adventure situation is generally defined as a new experience marked by uncertainty and novelty. It is influenced by the state of mind, attitude, and perceived competence to undertake a challenge (Priest & Gass, 2018). In OTs, for some, adventure comes from experiencing the group, while for others, it comes through experiencing nature or being active outdoors. To configure this, two sub-dimensions can guide the facilitator’s decisions regarding the activities to select: the level of adventure and the amount of dissonance induced by the experience.

In the context of OT programs, the interaction between differing amounts of risk and competence creates various challenges (Priest & Gass, 2018). As proposed by Martin and Priest (1986), the balance between these two variables will allow different levels of adventure to be experienced as in Figure 3. For a challenge to be experienced positively, it must represent a certain level of technical difficulty adapted to the physical and psychological skills of the participants (Martin & Priest, 1986; Priest & Gass, 2018). In this way, they will be more inclined to face and overcome the challenge, which will then allow them to better perceive their strengths and limits (Priest & Gass, 2018; Prouty et al., 2007). However, this sub-dimension of adventure cannot be configured without considering the level of dissonance experienced by individuals.

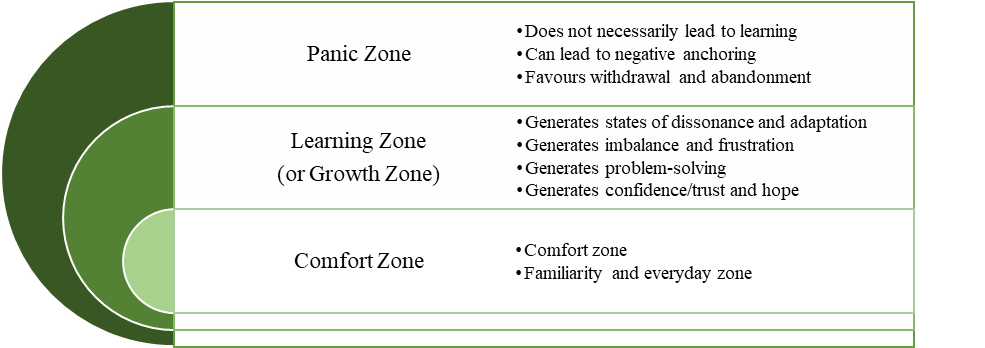

Dissonance is related to the gap between a person’s everyday environment and the new conditions in which they find themselves (Festinger, 1957). Adapting Vygotsky’s learning theory (1985), various works from the 1980s approached dissonance from the concept of proximal zone of growth as in Figure 4. When the degree of dissonance is slightly higher than the usual degree of physical, emotional, psychological, or social comfort, the person must mobilize their strengths and coping strategies or develop new ones in order to learn or grow (Festinger, 1957). This leaning and growth promotes intrapersonal and interpersonal relational benefits.

The complexity of configuring the adventure level in OTs arises from the various destabilizing factors inherent in adventure. The key to proper use requires a comprehensive understanding of participants’ characteristics. On one hand, different types of activities can be used to achieve this. In fact, beyond the use of technical activities, all kinds of generic activities, i.e. tasks related to living in the natural environment (e.g. setting up tents, building a fire), as well as experiential activities can help to meet these objectives. On the other hand, adventure can be experienced through physical, emotional, psychological, or social aspects, either individually or in a group.

Choosing which aspect to focus on is therefore important, especially with respect to activity choice and sequencing. In this manner, participants will be able to minimally regain the external boundaries of their habitus or the way they perceive and respond to the adventure. If the level of discomfort with the risks surpasses their abilities, the experience could have a negative outcome (Gargano, 2020). Therefore, assessing the adventure dimensions based on the purpose set by the OT program is crucial to success.

Group Experience

On the one hand, while OTs are not limited to group settings, their history has been shaped by classic adventure programs (e.g., Outward Bound schools) and holiday camps (White, 2020) that have influenced the role of groups in OTs. On the other hand, socially engaged adventures have existed for millennia in ancient and Indigenous societies, where groups were formed naturally in order to meet life challenges (Leclerc, 1999). No alternatives existed, other than being in the community one was born to and contributing through work to survive and provide for one’s family necessities (Anzieu & Martin, 1982). This vision of the group has gradually evolved with the needs of modern societies and cultures.

Today, group experience responds to needs for affiliation, affection, and recognition, which are fundamental to all human beings (Leclerc, 1999; Turcotte & Lindsay, 2019). The context of nature and adventure, to a certain extent, naturally provides opportunities to meet these needs. However, the group can have both favorable effects, like a sense of belonging, and adverse effects, like a feeling of rejection.

Several factors related to the context of intervention are likely to influence the quality of relationships. For instance, factors such as uncertainty and destabilization in the experience, the harshness of the context, the quantity and complexity of technical tasks, such as navigating a river in a canoe or climbing a mountain while roped together, and skills related to living in nature, such as setting up a camp, cooking, or building a shelter, foster interdependence among group members. These factors contribute to explaining the role of interdependence in generating benefits (Dimmock, 2009; Gargano, 2020).

The group is strongly connected to other pivotal factors, particularly the dissonance concept, which alters interpersonal relationships. On the one hand, outdoor tasks promote interaction. On the other hand, the context facilitates unlocking individuals’ strengths (Gargano & Turcotte, 2017). Consequently, this fosters collaborative relationships based on the interdependence of the tasks at hand (Gargano & Turcotte, 2017). OT facilitators must convey values of respect and inclusion in order to address the needs for belonging, acceptance, and affection that may emerge in group settings. These values must be reflected in their interventions to ensure meaningful and productive experiences for all of the participants (Mirkin & Middleton, 2014; Shooter et al., 2009). Finally, facilitators must be attentive to the group dynamics that are inherent in any group experience so as to intervene appropriately (Turcotte & Lindsay, 2019).

Physical Activity

Between the years 470 and 324 BC, Aristotle, Socrates, and other philosophers emphasized the importance of uniting body and mind and having experiences fostering this union for the benefit of holistic development (Ewert & Sibthorp, 2014). Although this recognition is not new, it is only in the past two decades that OT research has increasingly focused physical activity’s impact on health (Donnelly & MacIntyre, 2019; Hartig and al., 2014). Several authors have highlighted that engaging in physical activities in a natural environment can have positive effects on psychological health, such as reducing anxiety, physical health by increasing fitness, and social health, including promoting cohesion and support (Lawton et al., 2017; Perry, 2009; Shanahan et al., 2016). The intensity and duration of the activity are factors that influence these benefits.

In addition, the environment in which physical activity occurs, including blue and green spaces, are acknowledged for their potential to predict physical activity behavior (Donnelly & MacIntyre, 2019). Certain studies highlighted the impact of living near green spaces and its influence on the frequency of physical activity (Flowers et al., 2016). In addition to the activity setting, emphasizing that physical activity engagement in natural environments essentially acts to mediate the effects on social health (Home et al., 2012).

While physical activity does stimulate the release of hormones like endorphins, dopamine, and adrenaline that are associated with improved overall well-being (Legrand et al., 2023), its level must still be adapted to the capacity and level of each participant’s physical fitness. As with other key features, the level of exercise must be modulated according to the desired purpose and the abilities of individuals. If properly adjusted, participants can maintain their availability for the intervention, whereas a malignment may hinder the fulfillment of the desired objectives. Factors to be considered include the perception of being immersed in natural surroundings (Mackay & Neill, 2010), duration (Perry, 2009), intensity, and frequency (Shanahan et al., 2015).

Transfer

The aim of transfer is to consolidate the learning. It is a process that facilitates the retention of learning and its integration into individuals’ lives (Gass, 1999). Having received extensive attention for several years, the concept of transference stems from the principles of experiential learning (Priest & Gass, 2018). It is a key feature and must be configured prior to the implementation of OTs in terms of planned periods to promote transfer and retention (e.g., before, during, and after the activities). Different schools of thought have influenced the way transfer occurs in OTs. According to Priest and Gass (1999), their integration has changed over the decades, initially starting from an educational perspective.

First, in the 1940s, participants were given the freedom to reflect and learn from their own experience without external influence. This philosophy was based on the idea that learning is initiated by the natural environment itself. This perspective evolved in the 1950s to focus on a transfer method that included feedback from the activity instructor at the end of the activity. The 1960s marked a paradigm shift, inviting participants to reflect on the relationships between lived experiences and to articulate them in terms of the program purpose. The decade that followed was characterized by transfer methods that incorporated them in advance of the experience, with the aim of directing the learning achieved during the activity. In the 1980s, facilitators began to introduce activities by structured metaphors or isomorph, in order to facilitate a more direct learning experience. Finally, during the ’90s, techniques were intentionally used prior to the experience to reduce resistance to change.

Although transfer is among the key features to configure, various studies emphasized the complexity associated with integration, surpassing the mere implementation of these techniques (Brown, 2010; Gass & Seaman, 2012; Sibthorp, 2003). Furthermore, central to reflection on this key feature are the planned promotional periods (e.g., before, during, and after), the preferred techniques, and the means, such as metaphors, impact techniques, logbooks, solo contemplation, and group discussions. Indeed, the techniques selected should align with the pursued objectives during program planning. Among all the key features, this aspect remains one of the most concrete to orchestrate.

| Decade | Generation | Explanation |

| 1940s | Letting the experience speak for itself | Learning and doing |

| 1950s | Speaking on behalf of the experience | Learning by telling |

| 1960s | Funneling or debriefing the experience | Learning through reflection |

| 1970s | Frontloading (by direct method) the experience | Direction with reflection |

| 1980s | Framing (by isomorphic method) the experience | Reinforcement in reflection |

| 1990s | Frontloading (by indirect method) the experience | Redirection before reflection |

Relationship Between Facilitator and Participants

In the context of nature and adventure, various conditions contribute to the quality of the relationship between the facilitator and the participants (Ewert & Sibthorp, 2014; Gass et al., 2020). First, the nature of OT activities tends to stimulate the facilitator involvement, which alters the authoritative dynamic (Russell & Phillips-Miller, 2002). The diverse climatic conditions and the nature of challenges provide facilitators with unique opportunities for modeling and promoting collective values such as cooperation and mutual aid (Gass et al., 2020; Mirkin & Middleton, 2014). Moreover, these conditions also give them the opportunity to observe the participants from different angles and to intervene as need in particular situations (Bandoroff & Newes, 2004; Gass et al., 2020).

Certain qualities are required to intervene adequately in OTs and foster the quality of this relationship. These include integrity, benevolence, demonstration of technical proficiency, and interpersonal skills (McKenzie, 2000; Shooter et al., 2009). However, different groups of authors recognize the complexity of the knowledge required to perform this task (Gass et al., 2020; Priest & Gass, 2018; Schumann et al., 2009). They highlight the importance of technical skills in this type of intervention, as well as the need to establish work teams with diverse skills to ensure the success of the program. This includes proficiency in technical skills, related natural environment, and group dynamics (Bunce, 1997; Priest & Gass, 2018). One solution is to create multidisciplinary teams (Priest & Gillis, 2023).

Proposal for a Planning Tool

In this chapter, we delineated the key features necessary to plan OTs. To further understand them, we explained their sub-dimensions and suggested ways to integrate them in practice. Ultimately, this knowledge can be converted into practice to optimize the impact on participants. However, despite this knowledge, a certain complexity remains.

In fact, guidelines to plan OTs beyond the recognition of the theoretical foundations to derive and define key features are unavailable. According to the literature, the mere incorporation of knowledge is not sufficient to guarantee the success of the intervention (Gargano, 2021). Combining the key features of OTs requires judgment and skill on the part of the facilitators. To assist in the planning of OTs and to enable the practical integration of key features, an OT planning tool is offered for consideration. This tool is designed to serve anyone seeking to explain the OT plans, whether to students or novice or experienced facilitators.

To create this exploratory planning tool, the following mehodology was used but has not yet been validated. It involved the first author generating a list of questions based on the descriptions of the five key features. These questions stemmed from a blend of theoretical expertise and extensive observational and pragmatic knowledge in establishing and conducting OTs. Two co-authors analyzed these questions, enabling them to sort and rephrase the list into a questionnaire. A final version of the planning tool resulted in Table 2.

| Support Grid for the Planning of Outdoor Therapy

Gargano, Pellerin, & Létourneau (2023) |

| Answer each of the statements. |

| Initial Questions |

| What is the purpose of the program? |

| What are the needs of participants? |

| What are the strengths of the participants? |

What are the characteristics of the participants at the:

|

| Are there exclusion criteria to consider depending on the intended purpose? |

| Nature Immersion |

| Where to perform the program? What means of transportation and accommodation are available? |

| At what time of year and season should this program be offered? |

| What is the average level of comfort in nature for these people? |

| What degree of immersion is desirable to achieve the objectives? |

| Which activities make sense with the objectives and will allow participants to experience sufficient sensory contact with nature? |

| Is this sensory contact desirable for these people or not? If so, how can we engage the senses in the experience? |

| Adventure |

| What is the most relevant technical activity for achieving the targeted objectives? |

| If we can’t achieve our objectives by implementing technical activities, what generic and experiential activities could we put in place? |

| What is the average level of competence (physical, emotional, psychological, and social) of people towards the activities selected? |

| What aspect (physical, emotional, psychological, and social) and degree of dissonance is desirable to achieve the objectives? What adventure activities could help to achieve these objectives? |

| How to scale the level of challenge before, during, and after the program (e.g., technical preparation before departure)? |

| If environmental conditions are moderate or difficult, will this influence the level of challenges associated with the activity? |

| What resources are necessary to implement so that participants can regain a certain zone of stability after having met the planned challenges (e.g., cabin, heat source, camp, alone time, free time)? |

| Group |

| How will the group experience achieve the desired objectives? |

| What is the group’s contribution to the process? |

| What is the ideal group size? |

| What is the usual level of social skills and comfort of these people when in groups? |

| What are the challenges related to the group experience and what means will be implemented to address them? |

| How will participants enjoy individual moments and is this desirable? |

| Physical Activity |

| What is the total duration of the program? |

| What are the physical and psychological capacities of these people? Is the duration of the program and its intensity sustainable for the people taking part? |

| How can the level of physical activity in the program be graduated to support the achievement of objectives? |

| Would it be necessary to physically prepare the participants to perform the activities (e.g., prior meetings)? |

| If the environmental conditions are favourable or challenging, will they impact the level of physical effort required and the achievement of goals? |

| Will participants be psychologically available for discussions or exchanges if this is planned and desired in the program in addition to physically demanding activities? |

| Transfer |

| What activities will be used to facilitate the transfer? |

| Are the program objectives clearly stated to the group? |

| What will be the preferred transfer technique? Should the relationship between objectives and activities be explicit or not in order to achieve the intended objectives? |

| Who will be responsible for this aspect of the program and for which activities? |

| What tools are recommended to make the planned transfers a reality (e.g., logbooks)? |

| Are the techniques consistent and realistic with the context of the program? |

| What are the targeted times (before, during, after) to perform the transfer? Was the schedule designed based on this aspect (e.g., distance to be covered based on planned transfer activities)? |

| What are the target locations for transfer activities (e.g., promoting attention, ensuring privacy or confidentiality)? |

| Relationship Between the Facilitator and the Participants |

| What are the five core values of the team of facilitators regarding the program? |

| What are the means and times planned to convey these values within the group? |

| What are the strengths and skills of the team members (e.g., knowledge of the population, comfort in a natural environment, technical skills and risk management, comfort in group intervention) and how will they be used? |

| What are the roles of each team member? What are the areas of overlap? |

| What is the supervision ratio needed for each activity to support participants in achieving their objectives? |

Conclusion

This chapter aimed to expose the key features that influence the impacts identified within OTs, first by explaining them theoretically and then by discussing the ways to configure them. These were the key features: immersion in nature, adventure, group experience, levels of physical activity, type of transfer, and the relationship between facilitator and participants. An OT planning tool was proposed to ease the implementation of key features in practical settings.

In future studies, testing this preliminary tool to determine its strengths and limitations would be beneficial. Stressing that the key features apparently serve as both mechanisms of change and effects, and their interrelation poses a challenge in evaluation is essential to consider. Further studies on this perspective would be appropriate. A more thorough comprehension of the processes involved in OTs could enable the optimization of the impact on the participating populations. Furthermore, ongoing research suggests that underlying theories for achieving benefits may surface and require further study.

References

Bandoroff, S., & Newes, S. (2004). Coming of age: The evolving field of adventure therapy. Association for Experiential Education.

Beckmann, J., Igou, E. R., & Klinger, E. (2019). Meaning, nature and well-being. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical activity in natural settings: Green and blue exercise (pp. 95-112). Routledge.

Bratman, G. N., Anderson, C. B., Berman, M. G., Cochran, B., de Vries, S., Flanders, J., Folke, C., Frumkin, H., Gross, J. J., Hartig, T., Kahn, P. H. J., Kuo, M., Lawler, J. J., Levin, P. S., Lindahl, T., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Mitchell, R., Ouyang, Z., Roe, J., Scarlett, L., Smith, J. R., van den Bosch, M., Wheeler, B. W., White, M. P., Zheng, H., & Daily, G. C. (2019). Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Science Advances, 5(7), 2375-2548.

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The Impacts of Nature Experience on Human Cognitive Function and Mental Health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249(1), 118-136.

Brown, M. (2010). Transfer: Outdoor Adventure Education’s Achilles Heel? Changing Participation as a Viable Option. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 14(1), 13-22.

Bunce, J. (1997). Sustaining the Wilderness Therapist. In C. M. Itin (Ed.), Exploring the Boundaries of Adventure Therapy: International Perspectives (pp.178-188). Association for Experiential Education.

Calogiuri, G., Litleskare, S., & MacIntyre, T. E. (2019). Future-Thinking Through Technological Nature: Connecting or Disconnecting. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise (pp. 279-298). Routledge.

Darcy, P. M., Jones, M., & Gidlow, C. (2019). Affective Responses to Natural Environments: From Everyday Engagement to Therapeutic Impact. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise (pp. 128-151). Routledge.

Davis-Berman, J., & Berman, D. (1994). Wilderness Therapy: Foundations, Theory, and Research. Kendall Hunt.

Dimmock, K. (2009). Finding Comfort in Adventure: Experiences of Recreational SCUBA Divers. Leisure Studies, 28(3), 279-295.

Donnelly, A. A., & MacIntyre, T. E. (2019). Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise. Routledge.

Ewert, A. W., & Sibthorp, J. (2014). Outdoor Adventure Education: Foundations, Theory, and Research. Human Kinetics.

Fernee, C. R., Mesel, T., Andersen, A. J. W., & Gabrielsen, L. E. (2019). Therapy the Natural Way: A Realist Exploration of the Wilderness Therapy Treatment Process in Adolescent Mental Health Care in Norway. Qualitative Health Research, 29(9), 1358-1377.

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Flowers, E. P., Freeman, P., & Gladwell, V. (2016). A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Predictors of Visit Frequency to Local Green Space and the Impact this Has on Physical Activity Levels. BMC Public Health, 16(420), 3050-3059.

Fromm, E. (1964). The Heart of Man, its Genius for Good and Evil. Harper & Row.

Gaekwad, J. S., Sal Moslehian, A., Roos, P. B., & Walker, A. (2022). A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Evidence for the Biophilia Hypothesis and Implications for Biophilic Design. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1-20.

Gargano, V. (2020). Les facteurs d’aide: Pour une meilleure compréhension des éléments-clés de l’intervention en contexte de nature et d’aventure. Groupwork, 29(1), 87-107.

Gargano, V. (2021). L’intervention en contexte de nature et d’aventure [vidéo]. Retrieved from https://virginiegargano.wixsite.com/recherche/medias

Gargano, V. (2022). Les pratiques centrées sur la nature et l’aventure et le travail social : Perspectives disciplinaires et théoriques. Intervention, 155, 151-165.

Gargano, V., & Turcotte, D. (2017). L’intervention en contexte de nature et d’aventure: Une application de l’approche centrée sur les forces. Canadian Social Work Review, 34(2), 187-206.

Gass, M. (1999). Transfer of learning in adventure programming. In J. C. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.), Adventure programming (pp. 227-234). Venture.

Gass, M., Gillis, H. L., & Russell, K. C. (2020). Adventure Therapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 2 ed. Routledge.

Gass, M., & Seaman, J. (2012). Programming the Transfer of Learning in Adventure Education: An Update. In B. Martin & M. Wagstaff (Eds.), Controversial Issues in Adventure Programming (pp. 29-46). Human Kinetics.

Harper, N., & Dobud, W. (2021). Outdoor Therapies: An Introduction to Practices, Possibilities and Critical Perspectives. Routledge.

Hartig, T. (2004). Restorative Environments. Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology, 3, 274-279.

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 207-208.

Home, R., Hunziker, M., & Bauer, N. (2012). Psychosocial Outcomes as Motivations for Visiting Nearby Urban Green Spaces. Leisure Sciences, 34(4), 350-365.

Joye, Y., & De Block, A. (2011). ‘Nature and I Are Two’: A Critical Examination of the Biophilia Hypothesis. Environmental Values, 20(2), 189-215.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169-182.

Keniger, L. E., Gaston, K. J., Irvine, K. N., & Fuller, R. A. (2013). What Are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(3), 913-935.

Larousse. (2022). Kinesthésie. In Dictionnaire Larousse en ligne. Retrieved from https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/kinesth%C3%A9sie/45561

Lawton, E., Brymer, E., Clough, P., & Denovan, A. (2017). The Relationship Between the Physical Activity Environment, Nature Relatedness, Anxiety, and the Psychological Well-Being Benefits of Regular Exercisers. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1058), 1-11.

Leclerc, C. (1999). Comprendre et construire les groupes. Presses de l’Université Laval.

Legrand, F. D., Chaouloff, F., Ginoux, C., Ninot, G., Polidori, G., Beaumont, F., Murer, S., Jeandet, P., & Pelissolo, A. (2023). Exercise for the Promotion of Mental Health: Putative Mechanisms, Recommendations, and Scientific Challenges. Encephale, 49(3), 296-303.

Li, Q., Nakadai, A., Matsushima, H., Miyazaki, Y., Krensky, A. M., Kawada, T., & Morimoto, K. (2006). Phytoncides (Wood Essential Oils) Induce Human Natural Killer Cell Activity. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 28(2), 319-333.

Lohr, V. I. (2010). What Are the Benefits of Plants Indoors and Why Do We Respond Positively to Them ? Acta Horticulturae, 881(2), 675-682.

Mackay, G. J., & Neill, J. T. (2010). The Effect of Green Exercise on State Anxiety and the Role of Exercise Duration, Intensity, and Greenness: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(3), 238-245.

Martin, P., & Priest, S. (1986). Understanding the Adventure Experience. Journal of Adventure Education, 3(1), 18–21.

McKenzie, M. (2000). How Are Adventure Education Program Outcomes Achieved?: A Review of the Literature. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 5(1), 19-28.

Menardo, E., Brondino, M., Hall, R., & Pasini, M. (2019). Restorativeness in Natural and Urban Environments: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Reports, 1-21.

Mirkin, B. J., & Middleton, M. J. (2014). The Social Climate and Peer Interaction on Outdoor Courses. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(3), 232-247.

Newman, T. J., Jefka, B., Brennan, N., Lee, L., Bostick, K., Tucker, A. R., Figueroa, I. S., & Alvarez, A. G. (2023). Intentional Practices of Adventure Therapy Facilitators: Shinning Light Into the Black Box. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00933-0

Norton, C. L. (2010). Exploring the Process of a Therapeutic Wilderness Experience: Key Components in the Treatment of Adolescent Depression and Psychosocial Development. Journal of Therapeutics Schools and programs, 4(1), 24-46.

Norton, C. L., Tucker, A., Russell, K. C., Bettmann, J. E., Gass, M. A., Gillis, H. L., & Behrens, E. (2014). Adventure Therapy with Youth. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(1), 46-59.

Ohly, H., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Bethel, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Nikolaou, V., & Garside, R. (2016). Attention Restoration Theory: A Systematic Review of the Attention Restoration Potential of Exposure to Natural Environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B, 19(7), 305-343.

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining Child Maltreatment Through a Neurodevelopmental Lens: Clinical Applications of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(4), 240-255.

Priest, S. (2023). Six elements of adventure therapy: A step toward building the “Black Box” process of adventure. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 15(1), 12-33.

Priest, S., & Gass, M. (1999). Six Generations of Facilitation Skills. In J. C. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.), Adventure programming (pp. 215-218). Venture.

Priest, S., & Gass, M. (2018). Effective Leadership in Adventure Programming, 3rd ed. Human Kinetics.

Priest, S. & Gillis, H.L. (2023). The tri-competent adventure therapist compared with the certified clinical adventure therapist. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 15(1), 105-118.

Prouty, D., Panicucci, J., & Collinson, R. (2007). Adventure Education: Theory and Applications. Human Kinetics.

Pryor, A., Carpenter, C., & Townsend, M. (2005). Outdoor Education and Bush Adventure Therapy: A Socio-Ecological Approach to Health and Wellbeing. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 9(1), 3-13.

Ratcliffe, E. (2021). Sound and Soundscape in Restorative Natural Environments: A Narrative Literature Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(570563), 1-8.

Rogerson, M., Barton, J., Pretty, J., & Gladwell, V. (2019). The Green Concept: Two Interwining Pathways to Health and Well-Being. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise (pp. 75-94). Routledge.

Rogerson, M., Kelly, S., Coetzee, S., Barton, J., & Pretty, J. (2019). Doing Adventure: The Mental Health Benefits of Using Occupational Therapy Approaches in Adventure Therapy Settings. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise (pp. 241-255). Routledge.

Russell, K. C., Gillis, H. L., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2017). Process Factors Explaining Psycho-Social Outcomes in Adventure Therapy. Psychotherapy, 54(3), 273-280.

Russell, K. C., & Phillips-Miller, D. (2002). Perspectives on the Wilderness Therapy Process and its Relation to Outcome. Child and Youth Care Forum, 31(6), 415-437.

Schertz, K. E., & Berman, M. G. (2019). Understanding Nature and its Cognitive Benefits. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(5), 496-502.

Schumann, S. A., Paisley, K., Sibthorp, J., & Gookin, J. (2009). Instructor Influences on Student Learning at NOLS. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 1(1), 15-37.

Scopelliti, M., Carrus, G., & Bonaiuto, M. (2018). Is it Really Nature that Restores People? A Comparison with Historical Sites with High Restorative Potential. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1-12.

Seuront, L. (2010). Fractals and Multifractals in Ecology and Aquatic Science. CRC Press.

Shanahan, D. F., Franco, L., Lin, B. B., Gaston, K. J., & Fuller, R. A. (2016). The Benefits of Natural Environments for Physical Activity. Sports Medicine, 46(7), 989-995.

Shanahan, D. F., Fuller, R. A., Bush, R., Lin, B. B., & Gaston, K. J. (2015). The Health Benefits of Urban Nature: How Much Do We Need? BioScience, 65(5), 476-485.

Sheffield, D., & Lumber, R. (2019). Friend or Foe: Salutogenic Possibilities of the Environment. In A. A. Donnelly & T. E. MacIntyre (Eds.), Physical Activity in Natural Settings: Green and Blue Exercise (pp. 3-14). Routledge.

Shin, S., Browning, M. H. E. M., & Dzhambov, A. M. (2022). Window Access to Nature Restores: A Virtual Reality Experiment with Greenspace Views, Sounds, and Smells. Ecopsychology, 14(4), 253-265.

Shooter, W., Paisley, K., & Sibthorp, J. (2009). The Effect of Leader Attributes, Situational Context, and Participant Optimism onTrust in Outdoor Leaders. Journal of Experiential Education, 31(3), 395-399.

Sibthorp, J. (2003). Learning Transferable Skills Through Adventure Education: The Role of an Authentic Process. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 3(2), 145-157.

Staats, H. (2012). Restorative environments. In S. D. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology (pp. 445–458). Oxford University Press.

Taylor, R. P. (2021). The Potential of Biophilic Fractal Designs to Promote Health and Performance: A Review of Experiments and Applications. Sustainability, 13(2), 1-24.

Turcotte, D., & Lindsay, J. (2019). L’intervention sociale auprès des groupes (4 ed.). Gaetan Morin.

Ulrich, R. S. (1981). Nature Versus Urban Scenes: Some Psychophysiological Effects. Environment and Behavior, 13(5), 523-556.

Van den Berg, M. M., Van Poppel, M., Van Kamp, I., Ruijsbroek, A., Triguero-Mas, M., Gidlow, C., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Grazuleviciene, R., van Mechelen, W., Kruize, H., & Maas, J. (2019). Do Physical Activity, Social Cohesion, and Loneliness Mediate the Association Between Time Spent Visiting Green Space and Mental Health? Environment and Behavior, 51(2), 144-166.

Van Hedger, S. C., Nusbaum, H. C., Clohisy, L., Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., & Berman, M. G. (2019). Of Cricket Chirps and Car Horns: The Effect of Nature Sounds on Cognitive Performance. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26(2), 522-530.

Vygotski, L. S. (1985). Pensées et langage. Éditions sociales.

White, W. (2020). A History of Adventure Therapy. In M. Gass, H. L. Gillis, & K. C. Russell (Eds.), Adventure therapy: Theory, research and practice (pp. 22-62). Routledge.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia, the human bond with other species. Harvard University Press.

Zosimov, V. V., & Lyamshev, L. M. (1995). Fractals in Wave Processes. Physics-Uspekhi, 38(4), 347-384.