7 Accessible, Adaptive, and Inclusive Outdoor Recreation

Carinna Kenigsberg and Jason Cole

A person’s life can change in an instant. An avid explorer can acquire an injury that prevents them from hiking; a parent with a neurodiverse child may need to become aware of sensory supports while camping; a child could develop an illness that requires them to only engage in supervised activities. To move forward and continually evolve, our profession needs to understand that anyone at any time may require support to connect to nature and be active in the outdoors. Practitioners need to stay relevant in their skills and be ready to support all types of people in a way that suits them best and creates optimal experiences.

I could have never gone on the camping trip by myself. I slept outside and heard the sound of the river. Staying in nature was a whole new level of connection: (more) than just a few hours that I was used to experiencing – Power To Be Participant.

Developing and delivering outdoor programs for people with diverse abilities requires a blend of person-centered and interpersonal approaches with technical skills and competencies. To design and deliver a quality outdoor experience, one must consider multiple perspectives, including how to best engage participants while keeping everyone safe: this is where practitioners look to and learn from those with lived experiences along with the outdoor sector’s industry standards.

Introduction

Our organization, Power To Be, believes that access to nature is a fundamental right. We believe that everyone belongs in nature and “nature belongs in everyone” (Child, 2022). Power To Be works with community members and partners in different sectors, including people with many different lived experiences. Our goal is to change outdated narratives surrounding inclusion and accessibility so that we can connect more people to the beauty of our natural surroundings through attitudinal, behavioural, and organizational change. This chapter covers our overarching views, approaches, and perspectives around accessible and adaptive outdoor programs.

Championing inclusion is everyone’s responsibility, and all outdoor program professionals should see each participant as the expert of their own experience. Using their guidance will help ensure that offered adaptations are authentic. We also share experiences, observations, and insights from other like-minded partners who run inclusive and accessible outdoor programs in Canada.

At Power To Be, we believe that developing and delivering outdoor programs for people with diverse abilities is mutually rewarding. We know nature adapts all the time and humans can too. The guidelines we share in this chapter have helped position Power To Be as a leader in the outdoor industry, helping us maintain standards of excellence while upholding our philosophy and approaches to facilitating adaptive recreation experiences. We know that when you can create opportunities for people to develop relationships with themselves and others, there is a significant ripple effect of change.

For example, we have seen participants with autism develop their social skills and outdoor knowledge through our programs and subsequently heard that this also helped these individuals in school settings, at other camps, and in their family dynamics. We witnessed an individual with a fresh spinal cord injury go paddling on the lake with his family, and he shared that he hadn’t imagined they would be able to do something together like this again.

Doing this type of work (going beyond the activity and looking at the person holistically) requires an approach that blends interpersonal, person-centered, and technical skills and competencies. We look at outdoor-sector industry standards, but we also cross-reference those standards of practice with different social sectors and partners. The Executive Director of Rocky Mountain Adaptive, Jamie McCulloch, follows similar standards of practice and philosophies to Power To Be. Jamie states that Rocky Mountain Adaptive’s philosophy is about “No Limits”:

…we see limitless possibilities, not limitations. This philosophy propels us to do all we can to provide access and inclusive settings to our outdoor natural environments through sport and recreation. By working with individuals’ unique abilities and strengths, and providing specialized adaptive equipment, certified instructors, and trained volunteer support, we try to remove the barriers to participation.

We welcome everyone to join the movement, and together creating a future where all individuals have access to outdoor sport and recreation, in the many incredible natural environments our country has to offer, from coast to coast to coast (McCulloch, 2022).

Power To Be uses the guidelines below to maintain high standards and procedures while implementing a variety of inclusive outdoor experiences. The following chapter will break down how to run inclusive programs through four principles: Approaches, Attitudes, Accesses, and Adaptations.

Approaches and Attitudes: Principles to Expand Practices Around Adaptive and Accessible Programs

Inclusive and adaptive programs start with the first point of contact: how people are treated when they arrive at a location, how they envision themselves when they are researching a program, and how they are supported to register for a program. These considerations are part of the initial stages of running inclusive, adaptive, and responsive programs. You can add systems and protocols to organizational standards, but those standards need to be matched with a service approach that welcomes people in an authentic way by focusing on their interests, strengths and lived experiences. This can include:

- Having clear, essential eligibility requirements that view the person holistically, and identify their need, fit, and desire to be in the program before the registration begins.

- Having referral options for people who may want or need a different type of support than your organization can offer.

- Creating goal-oriented registration packages and processes that consider the physical, social, and emotional goals and abilities of the individual joining the program.

The ACE philosophy is one of the first concepts we teach our groups, regardless of age and ability. ACE is helpful because it is broken down into three different components and is often used in conjunction with a group contract, goals, or expectations to set everyone up for success.

- Accept All Abilities: This means encouraging participants to respect and accept the differences in all of us. For example, understanding and respecting that someone may fear heights or may need to hike at a slow pace.

- Challenge Yourself: We want our programs to be a safe space – where participants feel supported and cared for – so they can reach outside their comfort zone. Whether that is making a new friend or trying a new activity, we want our programs to be a place where participants are learning and growing.

- Encourage Others: Participants should be free of negativity when joining programs. We want staff and participants to bring a culture of care and support to programs. We are building community together, so we want it to be inclusive and supportive.

We feel that ACE is an important way to frame a group and to set the stage for positive and inclusive interactions. We like to say that “everyone carries an ACE card” and we help metaphorically bring it out and use it. We believe that everyone should have access to nature. To create this access, there needs to be an approach that views people as people and focuses on their abilities first. It is through this perspective that we can form authentic connections and be creative, adapt, and offer an optimal experience. Designing programs that focus on people’s abilities, strengths, and experiences includes more than physical access. Ability-centered programs must include:

- Sense of inclusion: This is key in order to support the independence, comfort, and self-esteem of people with diverse needs and create deeper connections to places, people, and spaces.

- Equal participation: People with diverse needs should have equal access to opportunities, and programs should adapt as needed based on the varying supports.

- Universal language: e.g. clear, concise language and activity classification and clear visuals on signage.

When you meet a person where they are at by putting aside your own expectations, respecting the other person’s perspective, amd focusing on the things they enjoy doing, you can find moments within programs to co-create that sense of satisfaction, independence, and love for being out in nature.

Kayaking with Power To Be allowed my husband and I to go kayaking with our son. Kayaking gives him the freedom to enjoy being on the water while leaving his wheelchair on the dock. –Power To Be Participant

This is a shift in mindset and practice, and it’s easier said than done. Our society naturally gravitates toward assessing challenges and deficits instead of meeting people with authentic curiosity and respect. An ability-centered perspective should be carried out in all areas of an organization: in this way, there is shared leadership and practice, and individuals engaging with you will feel a sense of consistency, which builds trust.

Here is an example of this mindset and practice in action. In Power To Be kayaking programs, we typically incorporate all ages and abilities into all groups. Upon first contact, we greet everyone and begin assessing their ability, comfort, and experience with kayaking. We have many different paddle aids, pontoons, seats, and gloves. We discuss with each person what they would need to feel comfortable by building on their experiences, and we try to respond to their unique abilities and passions. For example, when one of the adults with a visual impairment expressed how he loves the sounds of the paddle hitting the water and the way the voices echo on the water as he paddles, we thought about how we could enhance that experience. We knew that in previous sessions when he was in the kayak, he was a very strong paddler, so we decided we would place him in the front of a double kayak with someone who was skilled at navigation but had less upper body strength. That way, he could be in control of his speed, and it would give him a chance to enjoy the sounds and rhythms of his paddling. Similarly, when a youth with autism was asking many questions about where we were paddling, we saw this as an opportunity for education and engagement rather than a hindrance, so we showed him the route chart and invited him into the navigation conversations. These examples of specific pairings by strengths and abilities allowed us to remove day-to-day barriers people face and create tailored experiences that leave lasting impressions.

The Challenge by Choice philosophy (Rohnke, 1989) strives to give each participant the opportunity and choice to challenge themselves to the limit of their personal comfort level. All programming is designed to be participant-centered and respects individual choices by placing value on safety, comfort, and participation to maximize learning and connection. Participants are encouraged to take part in all activities but always reserve the right to pass or choose another role within the activity.

When creating programs for people who are new to an activity, offering clear choices about what they “can” do vs what they “cannot” do is helpful. For example, when facilitating a rock-climbing program for a group of youths with autism, one of the participants was very cautious. He was nonverbally (through sounds and gestures) expressing worry about climbing and putting the harness on. We showed him two harnesses and asked which one he wanted to put on. Rather than asking him if he wanted to put on a harness, we showed him two and asked him which one he preferred: this tactic empowered his leadership, made him feel in control, and ensured he was wearing the safety equipment. Over the session, he became more comfortable with the activity and wearing the harness, and by the following session, he understood the steps he needed to do to go rock climbing. Both of his climbing sessions were successful in their own way and empowered participation through choice. By meeting people where they are at in the beginning of every program, we can help build trust and develop the structure of the program in ways that develop skill progression over time.

Being prepared is a guiding principle to achieving quality programs. It involves checking in with yourself, your co-staff, and participants. It also involves facilitating the intake and registration of the people who are part of the program, reviewing the pre-program checklist, and making sure the appropriate steps are followed to run the activity. Being present in the program allows staff to fully engage with participants and focus on the success and safety of the program. Being playful with the program contributes to the overall success of the program, and playfulness is often what is most remembered by participants. Here are some questions to consider:

- What is outside of your control that you will need to understand and manage to ensure the experience is optimal? These are referred to as precipitating factors, and they include weather, sleep, food, experiences that are happening personally, medication people are on, how overcrowded a location is, the moon cycle, crisis in the community, etc.

- What is the state that people are in emotionally? How does everyone process socializing and respond to stimulus? This can affect group cohesion and the type of facilitation techniques needed. It is useful to assess where people are at through engaging with the individual and/or their caregivers ahead of time, and through experiential questions in the moment such as “What is your weather report?” (i.e. encouraging people to share if they’re feeling metaphorically “sunny” or “stormy”). In this way, we can learn what state people are in so we can adapt the activity as necessary.

- What are the expected and unexpected outcomes of the program? How will things be adapted in the moment?

- What is the best way to create an inclusive experience from the first point of contact to the moment people arrive, both from an individual and group perspective?

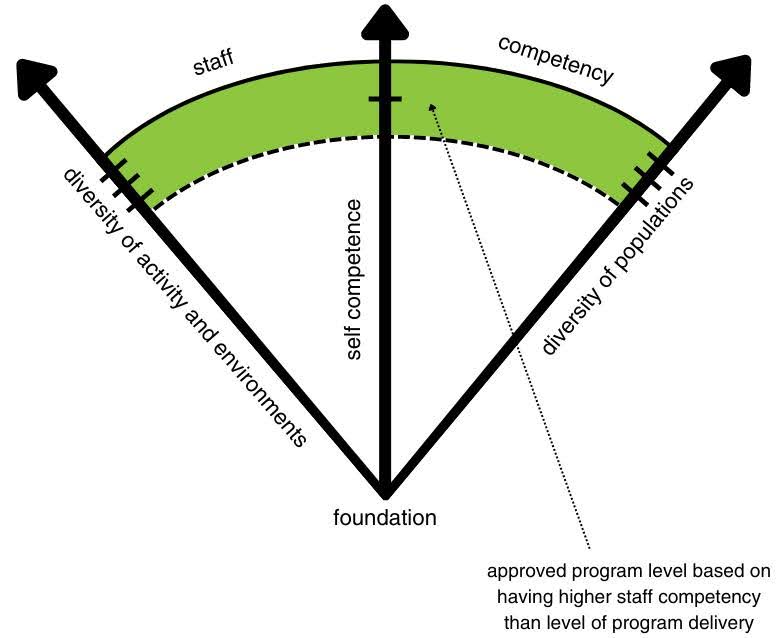

We have a model, shown in Figure 1, that is part of our pre-program process: to be Prepared, Present and Playful. As staff, we ask ourselves what our own comfort with the activity is, assess the group and the terrain, and then we ask what the comfort and experience of the group is. We aim to plan a program that is not beyond the skillset of our staff so that we can manage the expected and unexpected circumstances that may occur. This model assists with understanding where an individual’s scope of practice is and how much room there is to adequately manage the unexpected.

An example of a time when we adapted to unexpected circumstances was on a Power To Be kayaking expedition. A newer guide was leading the trip, and the weather and conditions had changed quickly. The staff member was not experienced in larger swells and strong winds, so as a result, they focused more on group safety than creating a unique kayak experience, as they had to guide more conservatively than originally planned.

In addition to assessing the staff and scope of the program, it is also important to have a baseline understanding of people’s behaviours. At Power To Be, we follow The Mandt System. Mandt is an interpersonal training system that illustrates how to manage dynamic behaviour by understanding the root cause, like what a person needs or is trying to communicate.

One of the Mandt models Power To Be uses regularly to be Prepared, Present, and Playful is RADAR. Radar stands for: Recognize, Assess, Decide, Act, and Review Results. The RADAR model, shown in Figure 2, helps staff develop situational awareness and make good decisions in situations that can sometimes be risky (The Mandt System, 2017).

There is so much complexity in our work and conditions are always evolving. RADAR gives staff the ability to recognize that things are changing and make the appropriate adaptations. Further, by understanding where the staff competency lies within the activity, and by understanding staff comfort and experience in supporting different abilities and learning styles, the activity can be tailored so that the staff are prepared to manage the unexpected and feel ready, willing, and able to modify as needed.

To be ability-centred is to view a person and their potential, not their limitations. Keeping the experience fair for everyone may include the need for adaptations based on participant needs. This results in full participation. To effectively deliver fun, fair, and authentic program experiences for participants, facilitators need to consider the following (Kunc, 2012):

- A person needs to be treated like a person and viewed as the expert of their own experience.

- A person who lives with a barrier is likely more innovative than their able-bodied support staff.

- Participants know best and can tell you how they can best be supported.

- Be curious, suspend judgment, and ask questions.

- Be flexible.

- Avoid over-adapting, which takes away the authentic experience for the individual.

At Power To Be, we aim for a balance of enjoyment, healthy risk, and safe procedures, and we keep authenticity at the forefront. For example, if the goal of canoeing is to feel the sensation of being on the water and we have too many ways to adapt the activity, then participants may miss out on the benefits of the experience. At times in the past, we have used too many adaptive devices to make people feel safe, and in the end, they felt too secure and did not enjoy the experience. Now, we set people up initially with adaptive supports and bring a few items with us in the canoe so we can check in along the journey and make sure to adapt and adjust as needed.

Merging the skills of outdoor leaders and therapeutic professionals invites an opportunity to look at individuals through a holistic perspective. This helps practitioners understand how the experience and the activity can also play a larger role in improving ability, knowledge, skill, and increase independence.

Accesses: Removing Barriers, Inviting Opportunity, and Creating Deeper Connections to the Outdoors

Before we can fully create access, we need to understand the barriers that participants are facing when engaging in outdoor programs and activities. As professionals, we must recognize that programs are one way to connect to nature, but to fully create access, we have to work in partnership with other sectors that are also trying to connect people to the outdoors. For example, Power To Be works closely with the local parks sector to provide workshops on how to work with people with diverse needs. We have offered suggestions for equipment and technology to use, infrastructure upgrades, specific signage that works for people with different abilities, and have reviewed sites and spaces and offered modifications to create more universal spaces.

For example, with some of our parks sector partners, we have suggested practices like ‘quiet hours’ and collaborated on projects like a welcome sign that BC Parks created to ensure that, upon first arrival to the parks, people of all backgrounds, cultures, and abilities feel welcome. We have partnered with outdoor tourism organizations to look at their service approach, imagery, signage, and activities to provide feedback and examples of how they can be more adaptive and expand their reach to people who otherwise would not be able to visit that tourist attraction. We have worked with municipalities on understanding their community goals to support people with disabilities and underrepresented populations and provided guidance to increase access to participation in recreation and access green spaces.

To remove barriers, we need to listen to the people who are facing barriers and see them as the expert of their experience. Table 1 is a list of barriers that participants with different lived experiences have encountered as they go about their lives, which they shared with Power To Be as part of consultancy sessions. When reading these, ponder whether the participants in your programs are facing similar barriers. Are there opportunities you can collaborate with other partners on and sectors to remove any barriers and create more access collectively?

There may be many barriers that people are facing in your community. It is innate for humans to jump toward quick and reactive solutions that try and solve many issues at once. However, by focusing on one aspect at time, you can look at options that could become long-term solutions instead of performing continuous reactive problem-solving.

Social

|

Economic

|

Physical

|

Emotional

|

For example, Power To Be was working with a regional park partner who was trying to create more access to their parks and increase opportunity for people with physical access challenges. When they began considering how they were going to fix some of the challenges, they first bought a piece of adaptive equipment and identified two trails that would be suitable for different physical abilities. We supported them in a discussion to identify the assets, resources, and staff expertise they had so we could understand how to broaden the park use to those with varying abilities. Then we categorized the list of ideas into four concepts, shown in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 2, called the four P’s of Access and Inclusion: Purpose, People, Place and Practice. Power To Be was working with parks-sector staff who wanted to purchase some adaptive equipment to enhance access to their trails. Before we recommended certain types of equipment, we asked which people would be interested in using the adaptive equipment. They explained that there were some local community organizations working with people who had experienced spinal cord injuries who would love to access the trails, and there were a few places that they wanted to take participants they felt would be suitable to increase park access. When we discussed the expertise among the regional parks staff, we identified areas of practice and skills they had internally, and expertise they would need to outsource. For example, their search and rescue team knew the trail back routes and had cabins that could house extra adaptive equipment and tools for repairs and modifications. We also spent time with park rangers to explore how their flora and fauna education could be taught in different ways, including hands-on visuals, sensory activities, discussion of infographics, wayfinding visuals, and symbols. We also discovered there is a volunteer group who cares for trail maintenance and hiking sessions.

Purpose

|

People

|

Place

|

Practice

|

The staff were thrilled with the idea of sharing the trails with more people. We explored all the aspects above separately with their staff, and then we tied all the pieces together so they could see how to move their practice as a team and perpetuate their purpose and goals within their region.

The following are some activities you can consider starting to engage with Purpose, People, Place, and Practice and gain a deeper understanding of emerging needs and opportunities. Consider these activities to increase access and inclusion:

- Research: Explore what other organizations are doing and learn about what is being created and provided in other regions.

- Accessibility audit: Invite consultants in who have different lived experiences (e.g. a wheelchair user, someone with low vision, neurodivergent people, etc.) to guide you through your facility and identify areas of opportunity to increase inclusion. Always honour their time and expertise.

- Speakers’ Series: Invite representatives from community organizations to give a talk on issues of importance to the community, ways to partner to reduce isolation, and hear what the current emerging needs are.

- Directory of Services (or Referral Services): Ensure that staff and volunteers have up-to-date information about the range of agencies and organizations within the community.

- Partnership Programs: Collaborate with local partners who have experience working with people with diverse needs and knowledge around emotional and physical adaptations and modifications, adaptive equipment, and mental health considerations. For example, you could plan an inclusive hike, facilitated in partnership with other organizations offering the use of a TrailRider for participants who may require one.

- Brainstorm: Find possible community partners and develop strategies for building relationships to enhance knowledge around places to explore, people to work with, and the practices and skills needed to create safe and enjoyable outdoor adventures.

Adaptations: Equipment Technology, Program Modifications, and Attitudinal Adjustments to Influence Change

Adaptations begin in the pre-program planning stages. This includes learning about the group’s makeup and what the individual and group goals are. What are the aspects of the program that are fixed and cannot change, and what are the aspects that can be altered? Being able to adequately adapt means that you have lots of options, choices, different gear, and backup plans. It means having a team that is in tune with their surroundings, has experience managing and developing groups, and is competent at facilitating the activities.

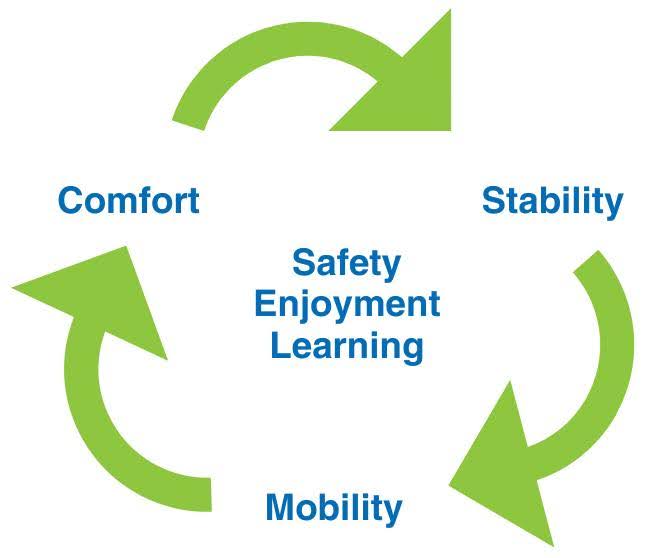

When you are using adaptive equipment, it is important to look at the emotional and physical safety of the participants. We break this down into three areas: comfort, mobility and stability, as shown in Figure 4. For example, is the device being used comfortable for the individual using it? Do they feel restricted, or can they move around? Do they feel stable and secure? Then there is the emotional side: Do they trust the staff to help them use the equipment? Do they feel safe, and are they being checked in with? If modifications need to be made, is this done by viewing the participants as the expert of their experience? When does technology assist with accessing natural spaces, and when does it hinder connection to natural spaces?

An example of technology that can help is assisted communication devices, which can be used to support wayfinding and learning about flora and fauna. Assisted communication devices create access for someone who communicates non-verbally or through sound or images. Some people may always need adaptive equipment that is managed by others, and some people may want to work towards more independence. This involves trying a variety of options. By being willing to adjust, adapt, and modify, you can support others to build competency and confidence, whether they are looking for a supported social experience or an independent experience.

Tips and tricks with technology and equipment

- Don’t assume one technology is going to work for everyone.

- Progression and developing competency may involve multiple types of equipment.

- Participants need options.

- Outdoor equipment is also an adaptive tool (e.g. maps, walking sticks, compass, charts etc.)

- When supporting someone transferring from one type of equipment (e.g. their wheelchair) to the outdoor equipment (e.g. a kayak with pontoons on it), ensure a proper lift and transfer can be facilitated.

- Adaptations and modifications can involve trying things several times.

- Ensure adaptations do not impact the safety of the participant or support staff for the sake of participation.

Some types of adaptive equipment:

- TrailRiders and other All-terrain devices (BowHead, It’s Not A Wheelchair, Mountain Trike, Action Trackchair, Beach Chair etc.)

- Access Tracks and/or Mobi Mats to create access on trails and beaches

- Items like noise-cancelling headphones, iPads, and communication boards

- Geocaching Tools like maps, charts, examples of things they will find, and examples of different containers for the geocache

- Cushions, mats, foamies

- Extra clothing, blankets, rain gear

- Gloves for different grip strength

- Repair kits and spare parts

- Information about the local history, flora, and fauna through stories, images, and tactile objects

- Walking sticks

- Wayfinding mapping technology like apps, picture or sensory boards, or landmarks

- Pontoons, adaptive seats, specialized cushions, devices that can be operated with a single arm

- Transfer benches

- Sensory activities like gardens, touch stations, spaces that change seasonally

Adaptations have the potential to remove a level of isolation and dependence, offering people a chance to feel in control and a part of their holistic experience.

You think some activities are just [in] your past life, but to be empowered to be able to do what I used to enjoy is amazing. –Power To Be Participant

Conclusion

All of us can naturally connect to the benefits of time spent in the great outdoors. Nature has been a co-facilitator for experiences in everyone’s lives. However, those living with barriers or disabilities have limitations to access some wild and natural places. When we work to remove those barriers and bring people with disabilities into nature, there is the opportunity to develop personal skills that improve health, aid in stress management, and gain socialization skills. “Many outdoor education programs focus on the development of personal skills, such as building self-esteem, personal fitness, and stress reduction,” (The Social Planning and Research Council of B.C., n.d.) which is why it is valuable to develop practices and approaches that broaden the notion of inclusion and access in the outdoors.

Inclusion begins in the first stages of any program or event. It starts through exploring the concept of welcoming approaches, creating access, and involving adaptations. These concepts can help to create more inclusive nature-based programs and opportunities and influence organizational strategies, approaches, and procedures and in a purposeful way these concepts can achieve social change.

Nature adapts all of the time, and humans can too. Adaptations should be fun, fair, and authentic and should always see the person as the expert of their own experience. Inclusion is everyone’s responsibility, and together, we shift the narrative in the outdoor sector and promote access for all.

References

Child, K. (2022, 09). Personal communication. Victoria, BC.

Cole, J. (2013, April 22-26). Program divergence model (Conference presentation). Power To Be Staff Training, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Cole, J. (2016, November 24-25). Program divergence model (Conference presentation). Risk Management Conference, Independent Schools Association of British Columbia, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Kunc, N. (2012). Personal communication. Victoria, BC.

McCulloch, J. (2022). Personal communication. Executive Director, Rocky Mountain Adaptive, Canmore, AB.

Rohnke, K. (1989). Cowstails and cobras II: A guide to games, initiatives, ropes courses, and adventure curriculum. Kendall Hunt.

The Mandt System. (2017). Using Your RADAR. Retrieved from https://www.mandtsystem.com/2017/07/06/using-your-radar/

The Social Planning and Research Council of B.C. (n.d.). SPARC BC. Retrieved from https://www.sparc.bc.ca/

Graphics used with permission of Power To Be