15 A New Holistic Model of Ecohealth Promotion

Stephen D. Ritchie; Jonah D’Angelo; Ginette Michel; Jim Little; and Sebastien Nault

Outdoor Learning (OL) in Canada is a broad umbrella term that reflects many diverse contexts and practices that ranges from recreation (including camping and tourism), through education and development, to therapy or therapeutic programs (Priest, 2023). According to Berman and Davis-Berman (2000), these OL designations reflect a continuum from low sophistication in programming leading to incidental outcomes (e.g., camping/recreation) to highly sophisticated programming leading to intentional outcomes (therapy).

In most contexts, OL involves a person’s mind, body, and emotions in a complex relationship with other people and nature in either a planned (intentional) or unexpected (incidental) manner. Other relationships would also include a connection with the cosmos (God, Creator, or higher power), especially when OL involves organizations with religious affiliations or Indigenous land-based programs. It is self-evident that OL reflects a positive, educational, developmental, or healing process, depending on the context. In other words, OL is helping people have fun and/or improve their lives in and with nature. Thus, it is not difficult to view OL through an ecohealth lens. This chapter aims to present a new Holistic Model of Ecohealth Promotion as a framework that can be used as a resource for OL programs, practitioners, and health promoters.

What Is Ecohealth?

A practice that adopts systems approaches to promote the health of people, animals, and ecosystems in the context of social and ecological interactions. Health is seen as encompassing social, mental, spiritual, and physical well-being and not merely the absence of disease. As a contraction of ecosystem approaches to health, ecohealth emphasizes human agency and systemic thinking to promote well-being and quality of life (Parkes et al., 2014, p. 1770).

This definition is broader and more holistic than the World Health Organization’s (WHO, 1948) definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (p. 1). Rather than the health of a person, ecohealth is concerned with developing and maintaining healthy reciprocal relationships between humans and the entire ecosystem within which they live, work, play, or learn.

The concept of ecohealth is similar to other concepts, such as one medicine and one health (Zinsstag et al., 2011); and global health and planetary health (Parsons, 2020). However, further comparisons of the similarities and differences are beyond the scope of this chapter, and they have been addressed elsewhere (Harrison et al., 2019). Ecohealth also has some similarities to approaches such as ecopsychology (Roszak et al., 1995), ecotherapy (Jordan & Hinds, 2016), and nature-based therapy (Harper et al., 2019). However, each of these disciplines has its unique literature base, and exploring the similarities and differences is also beyond the scope of this chapter.

What Is the Evidence for Holistic Health Benefits From OL in Nature?

Increasing evidence has been accumulating for the holistic health benefits that accrue through contact with nature and participation in various outdoor activities and programs. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are research designs that compile and summarize the strength of evidence from all the published studies related to the same research question or topic. Systematic reviews can use either qualitative or quantitative analyses to synthesize this evidence.

Qualitative analyses typically involve pooling outcomes as common themes across studies, and a meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis that pools all the numerical outcomes across studies together and then usually calculates an effect size (ES). An ES is a statistical way to calculate the magnitude of a change or improvement, and Cohen’s (1988) commonly accepted interpretation is that <0.2 is small, 0.5 is medium, and >0.8 is large. A positive ES indicates a positive change, and a negative ES indicates a negative change (1988). It should be noted that a small ES is not necessarily trivial, especially if the pooled outcomes from the included studies were statistically significant.

Many researchers consider systematic reviews and meta-analyses to be the most credible forms of evidence. Thus, drawing on the evidence from over one hundred diverse systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the following sections summarize some of this evidence related to the various holistic health benefits from varied OL contexts.

Camping/Recreation Systematic Review Evidence

In 1994, Cason and Gillis completed a meta-analysis of outdoor adventure with adolescents. Based on analysis of the 43 included studies, the mean effect size was 0.31, related to several different outcomes (self-concept, behaviour improvement, locus of control, clinical improvement, grades, school attendance). Marsh (1999) completed a meta-analysis on the organized camping experience for youth, and 22 studies were included for analysis yielding strong evidence that participation in camp enhanced self-construct, a broad term referring to self-development.

Walker and Pearman (2009) surveyed four independent systematic reviews on therapeutic camps for children and young people with chronic illnesses. They claimed that these camps enhance self-esteem, disease knowledge, emotional well-being, adaptation to illness, and symptom control (Pearman, 2009). According to Holland et al. (2018), participating in wildland recreation can lead to personal development, pro-social behaviours, mental restoration, and environmental stewardship; and Pierskalla et al. (2004) found that participation in outdoor recreation led to physical fitness, feeling healthier, skill acquisition, confidence, independence, and strengthened spirituality.

For students participating in campus outdoor recreation programs, the “benefits include[d] increased academic success, smoother transitions to college, better mental and physical health, lower levels of stress and anxiety, better and more numerous social connections, better intra- and interpersonal skills, increased environmental sensitivity, and better connectedness to nature” (Andre et al., 2017, p. 15).

Two meta-analyses related to challenge courses concluded that there was a statistically significant increase in self-awareness (Ferrell, 2017) and group effectiveness (Gillis & Speelman, 2008). Not surprisingly, the effect size (ES) was higher for therapeutic (0.67) and developmental (0.47) groups compared to educational (0.17) groups (Gillis & Speelman, 2008).

There were two systematic reviews summarizing the health benefits for children completed by the same research group from Canada. They concluded that: (1) spending increased time outdoors was related to increased physical activity, decreased sedentary behaviour, and improved cardiorespiratory fitness (Gray et al., 2015); and (2) risky outdoor play leads to increased physical activity and social health and decreased injuries and aggression (Brussoni et al., 2015). Pre-schoolers (2 – 5 years) were also found to be more physically active during outdoor play sessions (Truelove et al., 2018).

Education/Development Systematic Review Evidence

From an education and personal development perspective, a meta-analysis by Hattie et al. (1997) on adventure education compiled outcomes from 96 studies and reported an ES of 0.34 and a remarkable increase of 0.17 when follow-up assessments were completed. The outcomes in this study were diverse and included health-related categories such as self-concept, academic, personality, and interpersonal. Building on this earlier work, Laidlaw’s (2000) meta-analysis of outdoor education studies revealed that outcomes related to program goals had a higher ES (0.77) than those that were distally related (0.40). Fang et al. (2021) found a mean ES of 0.60 for enhanced self-efficacy for students in outdoor education programs.

Hans (2000) calculated an ES of 0.38 for a shift of locus of control from external to internal through participation in adventure programs. Ardoin et al. (2018) reported 121 unique outcomes (many health-related) in their systematic review of environmental education involving K-12 students. In a more recent systematic review, children ages 2-7 years participating in nature-based early childhood education programs seemed to improve their self-regulation, social skills, emotional development, nature relatedness, awareness of nature, and play interaction, although study authors warned that the evidence was low certainty (Johnstone et al., 2022).

A Cochrane Review, a special systemic review specifically focused on the health and well-being of adults related to their participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities, yielded inconclusive quantitative results (Husk et al., 2016). However, the qualitative results indicated that study participants reported high perceived benefits (Husk et al., 2016). Two environmental meta-analyses found that (1) human connection to nature influenced pro-environmental behaviour (Bamberg & Möser, 2007; Whitburn et al., 2020), and (2) an analysis involving structural equation modelling identified behavioural intention and morality as the social determinants most likely to predict pro-environmental behaviour (Bamberg & Möser, 2007).

Therapeutic/Therapy Systematic Review Evidence

In a meta-analysis of wilderness challenge programs for delinquent youth, Wilson and Lipsey (2000) calculated a small ES improvement of 0.18 for delinquency outcomes. Bedard et al. (2003) reported a moderate ES (although no overall ES was calculated) for wilderness therapy compared to traditional treatment for enhancing self-esteem/self-concept, improving interpersonal skills, and promoting positive behaviour change. In 2011, George completed a meta-analysis of outdoor behavioural healthcare (OBH) programs for adolescents. He calculated an ES of 0.45 from the 25 included studies adhering to OBH criteria (George, 2011), and Baker (2011) included 16 studies that met his inclusion criteria related to adventure and wilderness therapy and identified six main outcome areas: behavioural conduct, self-concept, self-esteem, mental health, locus of control and interpersonal skills.

Likely the most extensive systematic review and meta-analysis of adventure outcomes and moderators, Bowen and Neill (2013) included 197 studies in their analysis, calculated an overall ES of 0.47, and then suggested an ES of 0.5 as a benchmark for adventure therapy programs. They concluded “that adventure therapy programs are moderately effective in facilitating positive short-term change in psychological, behavioural, emotional, and interpersonal domains and that these changes appear to be maintained in the longer-term” (Bowen & Neill, 2013, p. 42).

Beyond these earlier studies related to therapeutic OL contexts, there have been systematic reviews reporting positive health benefits related to wilderness therapy for private pay clients (Bettmann et al., 2016), wilderness therapy compared to non-wilderness treatment programs (Gillis et al., 2016), adventure therapy impacts related to locus of control, self-efficacy, and self-esteem (Fleischer et al., 2017), talk therapy on natural outdoor spaces (Cooley et al., 2020), and the effects of forest bathing and nature therapy on mental health (Kotera et al., 2022).

Other Related Systematic Review Evidence

Beyond the systematic review evidence related to health benefits and OL in terms of camping/recreation, education/development, and therapeutic/therapy contexts cited above, there is a burgeoning evidence base of systematic reviews highlighting holistic health benefits from interactions with nature that do not necessarily fit directly within the OL paradigm. The following list of systematic reviews summarize diverse health benefits related to nature:

- Exposure to natural environments leads to modest improvements in emotional well-being (McMahan & Estes, 2015).

- Nature connectedness is related to positive affect (emotions), vitality, and life satisfaction (Capaldi et al., 2014).

- Nature-based outdoor activities improve depressive mood and positive affect (emotions); and reduce anxiety and negative affect (Coventry et al., 2021).

- Nature connectedness is positively correlated with eudaimonic (psychological) well-being (Pritchard et al., 2020).

- Exposure to natural environments improves working memory, cognitive flexibility, and attention control (Stevenson et al., 2018).

- Natural environments are more restorative than urban environments (Menardo et al., 2021).

- Exposure to the natural environment can lead to stress reduction (Yao et al., 2021).

- Interactions with nature for children and teenagers leads to improved mental well-being (Tillmann et al., 2018).

- Nature activities for children and young people improves their self-esteem, confidence, positive and negative affect, stress reduction and restoration, social abilities, and resilience (Roberts et al., 2020).

- Nature exposure improves children’s physical and mental health (Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2021).

- Early life nature experiences benefits mental health later in life (Li et al., 2021).

- Nature access for people with mobility impairments can benefit their physical, mental, and social well-being (Zhang et al., 2017).

- Nature-based interventions in institutional and organizational health settings provide diverse benefits for participants, although authors did not make specific health related claims (Moeller et al., 2018).

- Enhancing human–nature connectedness improves human health and environmental sustainability (Barragan-Jason et al., 2022).

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that many diverse health outcomes can accrue from simply being outside in nature without necessarily acting or behaving in a particularly prescribed manner. There are also an increasing number of systematic reviews emerging in recent years describing the health benefits related to living, working, and playing near green (land) space (Callaghan et al., 2021; Houlden et al., 2018; Jabbar et al., 2021; McCormick, 2017; Rahimi-Ardabili et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020) (Yuan et al., 2021). Two other systematic reviews describe the health benefits of blue (water) spaces (Georgiou et al., 2021) and blue care interventions (Britton et al., 2020). Exercising outside, often referred to as green or blue exercise in the United Kingdom, also seems to provide more health benefits compared to exercising inside (Brito et al., 2022; Hanson & Jones, 2015; Li et al., 2022; Thompson Coon et al., 2011; Yen et al., 2021).

Although the health and well-being benefits reported from these systematic reviews were positive, some of the study authors did indicate that the quality of evidence was low to medium in some of the included studies; however, taken together, the overwhelming number of studies and systematic reviews related to the holistic health benefits related to OL cannot be ignored. Since the benefits described here were from pooled results reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, it is beyond the scope of this chapter to provide specific details of individual studies, such as the description of the population, ages, sex, and type of program or experience. It is also beyond the scope of this chapter to explore all the accumulating evidence for the health specific benefits related to contact with nature; however, some of it is summarized further in the Nature Rx Chapter (Langelier et al., 2023). It is clear that there are many holistic health benefits associated with OL, and this is why the Holistic Model of Ecohealth Promotion was developed to further recognize, strengthen, and deepen that association.

Holistic Model of Ecohealth Promotion (HMEHP)

Ecohealth promotion is the intentional process of helping people to use their volition (will) and agency (action) to make personal decisions and think systemically about improving both their own health and that of the surrounding ecosystem or environment (Ritchie et al., 2022). To enhance personal and planetary health, people can be encouraged to embrace wellness practices in harmonious interactions with nature to aspire to a state of mutually beneficial relationships across six interwoven dimensions of well-being: physical, mental, emotional, social, spiritual, and ecological.

The critical difference between ecohealth and ecohealth promotion is intentionality, volition, and agency; ecohealth describes something, and ecohealth promotion intentionally does something. Thus, in promoting ecohealth, one is encouraging or teaching people to use their choices and behaviours to purposefully practice wellness in specific ways to achieve holistic health outcomes across the six interconnected dimensions of well-being.

Within the Holistic Model of Ecohealth Promotion (HMEHP), we define ecohealth as more than the absence of disease, illness, injury, and disability but as a state of complete physical, mental, emotional, social, spiritual, and ecological well-being that can be achieved through immersive interactions with nature. Although the terms well-being and wellness are often undefined or utilized interchangeably in the literature, in the HMEHP, the term well-being is used intentionally to refer to each of the six dimensions of ecohealth, and wellness refers to the pathway or promotion practice leading to holistic ecohealth (Ritchie et al., 2022).

In other words, ecohealth consists of six interconnected dimensions of well-being. Wellness practices are the evidence-based choices and behaviours that are the tools used on the journey or pathway towards holistic ecohealth. We use the term endohealth to refer to the three internal dimensions of physical, mental, and emotional well-being and the term ectohealth to refer to the three external dimensions of spiritual, social, and ecological well-being (Ritchie et al., 2022).

Since every person on earth will eventually experience diminished health, leading to death, it is essential to help people to thrive no matter where they are on the health continuum, from languishing (low psychological, emotional, and social well-being) to flourishing (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being).

It is important to note that the definitions of both physical and mental well-being include the absence of something (illness/injury/disorder/disability) and the optimization of something, or in the case of mental well-being, a state of flourishing or high psychological, emotional, and social well-being (Keyes, 2010). Thus, ecohealth promotion can intentionally help a person with or without a physical disability or chronic illness to flourish using available resources. For instance, a person with a disability that prevents them from walking or using their legs can still participate in OL (perhaps with equipment modifications or trained personnel to help) and implement many wellness practices, such as simply being physically active outdoors, to optimize their physical well-being. Similarly, ecohealth promotion can intentionally help a person with or without a mental illness to flourish (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being) using natural resources and wellness practices. Keyes (2010) tested this empirically and found that helping a person to flourish was both a prevention and promotion practice related to mental health. From a prevention perspective, a person already flourishing (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being) who then declined to a moderate level of flourishing was 3.7 times more likely to develop a diagnosable mental illness ten years later (Keyes, 2010). From a promotion perspective, a person who was languishing (low psychological, emotional, and social well-being) and who improved to a moderate level of flourishing reduced the risk by 50% of developing a diagnosable mental illness ten years later (Keyes, 2010).

By helping people to implement wellness practices in nature, ecohealth promotion can also provide a prevention or protection function from declining states of well-being. The concept of helping people to flourish also helps us understand how ecohealth promotion can be used by any OL practitioner regardless of their level of training. For instance, an OL practitioner can help a person to be physically well or flourish without being a physician. They can also help a person to be mentally well without being a psychologist or clinician by helping them flourish (rather than diagnosing and treating a mental illness). This is a crucial point differentiating the HMEHP and other approaches, such as those who contend that you must be a trained and licensed therapist to practice adventure therapy. Within the HMEHP framework, almost anyone can help people achieve holistic health benefits regardless of their level of training or type of credential (or lack thereof). In other words, OL practitioners should consider incorporating the HMEHP into their educational curriculum since anyone in society can help people achieve ecohealth outcomes regardless of their professional credentials.

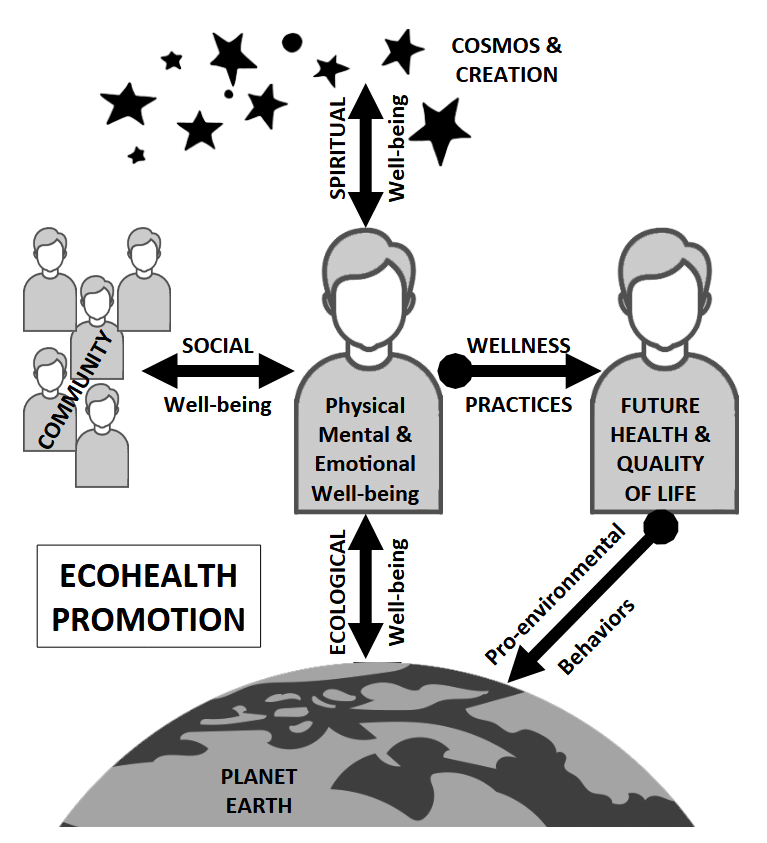

Figure 1 is a simple graphic portrayal of the HMEHP. It shows the relationships among the various dimensions. Table 1 contains pertinent definitions used in the remainder of this chapter.

Principles of Ecohealth Promotion

Ecohealth promotion has five foundational principles that interact and overlap in many healthy and synergistic ways:

- Natural Environment: It occurs when a person can continuously interact, connect, and develop holistic relationships within the ecosystem where they live, travel, or apply wellness practices. In other words, ecohealth promotion differs from other approaches to health promotion primarily because it focuses on applying wellness practices in nature and with nature (and in other outdoor contexts).

- Intentional: Evidence-based wellness practices are recommended or prescribed explicitly or designed implicitly (within a broader program design), so a person is encouraged to use their volition and agency to spend time in nature and to behave or act in ecohealthy ways.

- Homeostatic and Relational: The development process between a person and their interwoven well-being dimensions is a pursuit of complete internal homeostasis (endohealth) and positive external relationships (ectohealth) achieved through applying wellness practices.

- Harmonious and Balanced: This simply reflects systems theory and an inclusive view of striving to live a healthy life within a healthy ecosystem.

- Interrelated and Integrated: This reflects how all the dimensions of well-being are connected; many elements overlap and interconnect in reciprocal and mutually beneficial ways.

|

ENDOHEALTH is focused on homeostasis (an effort to maintain equilibrium); it consists of the three internal well-being dimensions (physical, mental, and emotional) reflected as interconnected and harmonious interrelationships within a person’s body and brain. |

ECTOHEALTH is characterized by relationships; it consists of the three external dimensions of well-being (social, spiritual, and ecological) reflected as interconnected and harmonious relationships with other people, the cosmos, and the planet. |

|

Physical well-being (PWB) is more than the absence of illness, injury, pain, or disability. It consists of a state of optimal functioning of the human body, and it includes various aspects such as cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, endurance, flexibility, balance, and body composition (Capio et al., 2014; Sharma-Brymer & Brymer, 2020) |

Social well-being (SoWB) is a state of optimal functioning in relationships, and it is characterized by having a sense of coherence and integration with other people, feeling acceptance and actualization in the presence of others, and contributing positively within a family and community (Cicognani, 2014; Keyes, 1998). |

|

Mental well-being (MWB), also known as cognitive, eudaimonic (Sharma-Brymer & Brymer, 2020), or psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995), is more than the absence of illness or disorder and consists of a state of optimal functioning characterized by self-acceptance, autonomy, personal growth, a sense of purpose in life, and environmental mastery (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). It also includes an intellectual element of engaging the brain in continual lifelong learning, including the application and sharing of knowledge (Mazurek Melynyk & Neale, 2018; Montoya & Summers, 2021; Stoewen, 2017; Swarbick, 2015), and it is the realization of one’s abilities, capacity to cope with life stressors, work productively, and make positive contributions to the community (World Health Organization, 2022). |

Spiritual well-being (SpWB), also sometimes described as religiosity (Peterson & Vann, 2014) and inclusive of cultural well-being (Manning & Fleming, 2019), is a state of optimal functioning that is characterized by having moral and ethical guidelines, accepting and embracing cultural and ancestral heritage, having a clear reason or purpose for life, feeling self-actualized and accepting of personal identity, believing in a higher power (God/Creator/ cosmos/universal consciousness/nature), and aligning personal behaviours with beliefs (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2009; Peterson & Vann, 2014; Shek, 2014). |

|

Emotional well-being (EWB), also known as affective (emotions, moods, and feelings), subjective (Diener, 2009), and hedonic well-being (Joshanloo, 2016), is a state of functioning characterized by maximized positive affect, minimized negative affect, and overall happiness, contentment, and satisfaction with life (Diener, 2009; Diener et al., 1999). |

Ecological well-being (EcWB), also described as environmental health (Bailey-McHale et al., 2020) or Indigenous well-being and the good life (Ritchie et al., 2015; Yadeun-Antuñano, 2020), is a reciprocal relationship between a person and their ecological system that is characterized by harmoniously and sustainably living, managing, harvesting, preserving, and distributing environmental resources for current needs while ensuring their availability for future generations and mitigating ecosystem degradation, pollution, and disease development (Grouzet & Lee, 2014). |

|

ENDOHEALTH PROMOTION is the process of using immersive interactions within nature to help people to improve their endohealth by focusing on homeostasis to maximize their physical, mental, and emotional well-being and, when necessary, managing, minimizing, or even curing their physical or mental illnesses. |

ECTOHEALTH PROMOTION is the process of using immersive interactions within nature to help people to improve their ectohealth by focusing on relationships to maximize their social, spiritual, and ecological well-being. |

Because every person on earth will eventually experience diminished health, leading to death, it is essential to help people to thrive no matter where they are on the health continuum from languishing (low psychological, emotional, and social well-being) to flourishing (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being).

The definitions of both physical and mental well-being include the absence of something (illness/injury/disorder/disability) and the optimization of something, or in the case of mental well-being, a state of flourishing or high psychological, emotional, and social well-being (Keyes, 2010). Thus, ecohealth promotion can intentionally help a person with or without a physical disability or chronic illness to flourish using available resources. For instance, a person with a disability that prevents them from walking or using their legs can still participate in OL (perhaps with equipment modifications or trained personnel to help) and implement many wellness practices, such as simply being physically active outdoors, to optimize their physical well-being. Similarly, ecohealth promotion can intentionally help a person with or without a mental illness to flourish (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being) using natural resources and wellness practices. Keyes (2010) tested this empirically and found that helping a person to flourish was both a prevention and promotion practice related to mental health.

From a prevention perspective, a person already flourishing (high psychological, emotional, and social well-being) who then declined to a moderate level of flourishing was 3.7 times more likely to develop a diagnosable mental illness ten years later (Keyes, 2010). From a promotion perspective, a person who was languishing (low psychological, emotional, and social well-being) and who improved to a moderate level of flourishing reduced the risk by 50% of developing a diagnosable mental illness ten years later (Keyes, 2010).

By helping people to implement wellness practices in nature, ecohealth promotion can also provide a prevention or protection function from declining states of well-being. The concept of helping people to flourish also helps us understand how ecohealth promotion can be used by any OL practitioner regardless of their level of training. For instance, an OL practitioner can help a person to be physically well or flourish without being a physician. They can also help a person to be mentally well without being a psychologist or clinician by helping them flourish (rather than diagnosing and treating a mental illness). This is a crucial point differentiating the HMEHP and other approaches, such as those who contend that you must be a trained and licensed therapist to practice adventure therapy. Within the HMEHP framework, almost anyone can help people achieve holistic health benefits regardless of their level of training or type of credential (or lack thereof). In other words, OL practitioners should consider incorporating the HMEHP into their educational curriculum since anyone in society can help people achieve ecohealth outcomes regardless of their professional credentials.

Wellness Practices

Wellness practices are evidence-based and characterized by intentional choices and behaviours people make taking steps to improve their holistic ecohealth. More specifically, within the HMEHP, wellness practices are defined as the pathway or journey, outdoors in nature, towards holistic ecohealth in all six dimensions of well-being (physical, mental, emotional, social, spiritual, and ecological). Thus, a wellness practice may promote one or several interrelated and integrated (Principle 5) dimensions of well-being. This section provides a few examples of wellness practices and how they contribute to helping a person improve one or more dimensions of well-being through interactions in nature or through a more intentional OL program element. In other words, a wellness practice can be simple and passive or more intentional, challenging, and complex; the key is that it is evidence-based. Creating a definitive list of all the evidence-based wellness practices related to promoting ecohealth is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, the vast majority of those profiled here were simply extracted from the systematic reviews cited earlier. Perhaps the first and most important wellness practice that is supported by the evidence, summarized from more than a dozen systematic reviews, is to interact outside within nature.

- Interact and connect with gardens (Gonzalez & Kirkevold, 2014; Nicholas et al., 2019; Ohly et al., 2016; Whear et al., 2014; Yeo et al., 2020)

- Walk though forests (Kotera et al., 2022; Mathias et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2020)

- Participate in activities on water (Britton et al., 2020)

- Use all senses in connection with other people (Barragan-Jason et al., 2022; Bowler et al., 2010; Browning et al., 2020; Capaldi et al., 2014; Coventry et al., 2021) (Gagliardi & Piccinini, 2019; Li et al., 2021; McMahan & Estes, 2015; Menardo et al., 2021; Orr et al., 2016; Oswald et al., 2020; Pritchard et al., 2020; Rahimi-Ardabili et al., 2021; Stevenson et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2021; Trøstrup et al., 2019; van den Bosch & Ode Sang, 2017; Yao et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2017)

- Reduce barriers (van den Berg et al., 2020) and inequities (Schüle et al., 2019) related to access

- Be physically active in nature each day or week, ideally for a minimum of two hours per week; peak health benefits accrue when spending at least three to five hours per week (Barton & Pretty, 2010; Coventry et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2019; Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011; Park et al., 2010; White et al., 2019)

- Engage in outdoor activities (Holland et al., 2018; Pierskalla et al., 2004; van den Bosch & Ode Sang, 2017; Yen et al., 2021), sports (Eigenschenk et al., 2019), and/or physical exercise outside on land or in water (Bowler et al., 2010; Brito et al., 2022; Coventry et al., 2021; Gagliardi & Piccinini, 2019) and with other people whenever possible (Hanson & Jones, 2015; Jansson et al., 2019; Lahart et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022; Thompson Coon et al., 2011)

- Encourage growing children to engage in self-directed, unsupervised, and risky outdoor play in nature (Brussoni et al., 2015; Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2021; Gray et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021; Marsh, 1999; Oswald et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2020; Tillmann et al., 2018; Tremblay et al., 2015; Truelove et al., 2018)

- Acquire knowledge about the environment and ecosystem health (Ardoin et al., 2018)

- Develop pro-environmental attitudes, behaviours, and habits (Holland et al., 2018; Mackay & Schmitt, 2019; Osbaldiston, 2004; Whitburn et al., 2020)

- Pray, meditate, and/or be mindful when engaged in nature and outdoor experiences (Barragan-Jason et al., 2022; Pritchard et al., 2020; Schutte & Malouff, 2018)

- Incorporate challenge course activities into your program where feasible or participate in challenge course activities where possible (Ferrell, 2017; Gillis & Speelman, 2008; Gillis et al., 2016)

- Increase the intentionality of achieving targeted goals (e.g. therapeutic outcomes) in your outdoor program (Bowen & Neill, 2013; Cooley et al., 2020; Gillis et al., 2016; Hattie et al., 1997; Marsh, 1999; Wilson & Lipsey, 2000)

- Lengthen the time you participate in or develop and deliver a nature-based immersive outdoor program (Coventry et al., 2021; Hattie et al., 1997)

- Live, work and play either within or as close to green and blue spaces as you can (Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2021; Gascon et al., 2017; Gianfredi et al., 2021; Green Analytics, 2020; Holland et al., 2018; Houlden et al., 2018; Jabbar et al., 2021; Kabisch et al., 2017; Kua & Lee, 2021; Lambert et al., 2019; McCormick, 2017; Peng et al., 2021; Rahimi-Ardabili et al., 2021; Rautio et al., 2018; Rojas-Rueda et al., 2021; Schüle et al., 2019; Taheri et al., 2021; Twohig-Bennett & Jones, 2018; Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018; Wendelboe-Nelson et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020)

- Teach and learn outdoors (Ayotte-Beaudet et al., 2017; Becker et al., 2017; Fang et al., 2021; Hattie et al., 1997; Laidlaw, 2000)

Readers may find that some (or all) of the wellness practice summarized here are very general or self-evident, and that is precisely one of the reasons we listed them here in this chapter. It highlights the remarkable synergy between ecohealth promotion and OL. In other words, many OL practitioners have been practicing ecohealth promotion for years, and one of the main reasons for introducing the HMEHP is to help provide rigor and credibility to OL, which can hopefully provide help with program development, funding requests, policy development, or simply obtaining permission to take students outside the classroom.

The other reason these wellness practice may appear general is related to the fact that the evidence is primarily from systematic reviews and meta-analyses where details from specific studies are lacking. More detailed and specific wellness practices can be synthesized from individual studies or studies related to a specific practice. For instance, although there is no systematic review (that we could find) related to the potential wellness practice of earthing or grounding, there is a relatively small body of evidence developing that the practice of earthing (connecting directly with the earth, such as walking barefoot or lying on the ground) can lead to improvements in several dimensions of well-being. A recent triple-blind (participant, tester, and data analyst) randomized control trial provided conclusive evidence that grounded sleeping reduced muscle damage and inflammation and improved recovery time for the experimental group compared to the control group after 20 minutes of intensive downhill running on a treadmill (Müller et al., 2019). Another double-blinded RCT reported improved mood in the experimental group after only one hour of being grounded while relaxing compared to the experimental group who were not grounded while relaxing (Chevalier, 2015). Neither of these studies were conducted outdoors.

However, although only singular studies, this type of research in outdoor contexts may lead to wellness practices in the future related to (1) sleeping or lying down outside on the ground after intense physical activity (e.g. climbing a mountain) to improve recovery, and (2) intentionally relaxing while being directly connected to the ground (e.g. sitting on a beach with bare feet buried in the sand or in a field with feet in the grass) to improve mood. There is still much work for future researchers to synthesize current research into evidence-based wellness practices and conduct future research studies to develop more wellness practices.

Contraindications

Although the evidence for the holistic health benefits related to OL is extensive, several contraindications need to be acknowledged. In other words, ecohealth promotion is not necessarily appropriate for all people, at all times, in all outdoor and natural contexts. Priest (2020) summarized the contraindications for participants related to outdoor therapy, and many of these likely apply to ecohealth promotion as well. Many of these are summarized in Table 2 (Priest, 2020) and the challenge and nature contraindications listed relate to different types of phobias or fears that may counteract or prevent someone from participating or benefiting from a particular wellness practice or ecohealth promotion activity.

The list of contraindications in Table 2 are primarily related to endohealth dimensions and social well-being (anthropophobia). Contraindications related to ectohealth could include misaligned spiritual values or beliefs related to OL programming (participant’s values or beliefs not aligned with the OL program); extreme environments that are excessively hot (Bruce-Low, Coterrell & Jones, 2006) or cold (Farrace et al., 1999; Farrace et al., 2003); excessively risky activities or risky activities with no effective risk management plan (Jackson & Heshka, 2011); certain seasons and weather conditions in particular geographies (Tucker & Gilliland, 2007); and other objective hazards such as, but not limited to, lightning, avalanches, floods, and steep terrain. Fortunately, many OL practitioners are aware and trained in risk management processes and practices, so addressing many of these contraindicators is not an insurmountable task. It should also be noted that these contraindications do not reflect the diverse array of nature contexts and participant preferences or aversions that could impact the benefits that accrue from a particular wellness practice or program. For instance, Gatersleben and Andrews (2013) found that outdoor environments with low levels of prospect (obscured field of vision) and high levels of refuge (places to hide) were not restorative and more likely to lead to increased stress and directed attention fatigue, and Bixler and Floyd (1997) found that 8th grade boys with high fear expectancy and disgust sensitivity preferred urban rather than wild environments.

|

CHALLENGE CONTRAINDICATIONS

|

NATURE CONTRAINDICATIONS

|

|

GENERALLY CONTRAINDICATED FOR:

|

|

Conclusion

There is now overwhelming evidence for the holistic ecohealth benefits related to OL and contact with nature. This chapter presents a new HMEHP that we hope will be helpful for OL practitioners and health promoters to use and apply in their leadership roles related to taking people outside and/or promoting health. The HMEHP can be used as a theoretical framework to inform OL or health promotion programs and program development where wellness practices are: (1) directly incorporated into the program as a primary modality; or (2) indirectly incorporated into a program as an adjunctive modality to support other targeted program goals. In other words, ecohealth promotion can occur through intentional programming or incidentally by focusing on other targeted goals and simply being active outdoors while incorporating wellness practices when convenient and synergistic with other program priorities.

References

Andre, E. K., Williams, N., Schwartz, F., & Bullard, C. (2017). Benefits of Campus Outdoor Recreation Programs: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 9(1), 15-25.

Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., Roth, N. W., & Holthuis, N. (2018). Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and analysis of research. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(1), 1-17.

Bailey-McHale, R., Ebrahimi, V., & Bailey-McHale, J. (2020). Environmental Determinants of Health. In W. Leal Filho, T. Wall, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, & P. G. Özuyar (Eds.), Good Health and Well-Being. Springer International Publishing. 171-179.

Baker, D. (2011). The Effects of Adventure and Wilderness Therapy: A Meta-Analytic Review [MPsy, James Cook University]. Townsville, Australia.

Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14-25.

Barragan-Jason, G., De Mazancourt, C., Parmesan, C., Singer, M. C., & Loreau, M. (2022). Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta-analysis. Conservation Letters, 15(1), 1-7.

Bedard, R. M., Rosen, L., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2003). Wilderness Therapy Programs for Juvenile Delinquents: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Therapeutic Wilderness Camping, 3(1), 7-13.

Berman, D. S., & Davis-Berman, J. (2000). Therapeutic uses of outdoor education. ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools, (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED448011), 1-6. Retrieved from http://www.ericdigests.org/2001-3/outdoor.htm

Bettmann, J. E., Gillis, H. L., Speelman, E. A., Parry, K. J., & Case, J. M. (2016). A Meta-analysis of Wilderness Therapy Outcomes for Private Pay Clients. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2659-2673.

Bixler, R., & Floyd, M. (1997). Nature is Scary, Disgusting, and Uncomfortable. Environment and Behavior, 29(4), 443-467.

Bowen, D., & Neill, J. (2013). A meta-analysis of adventure therapy outcomes and moderators. The Open Psychology Journal, 6, 28-53.

Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. (2010). A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health, 10(456), 1-10.

Brito, H. S., Carraça, E. V., Palmeira, A. L., Ferreira, J. P., Vleck, V., & Araújo, D. (2022). Benefits to Performance and Well-Being of Nature-Based Exercise: A Critical Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ Sci Technol, 56(1), 62-77.

Britton, E., Kindermann, G., Domegan, C., & Carlin, C. (2020). Blue care: a systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promotion International, 35(1), 50-69.

Brussoni, M., Gibbons, R., Gray, C., Ishikawa, T., Sandseter, E., Bienenstock, A., Chabot, G., Fuselli, P., Herrington, S., Janssen, I., Pickett, W., Power, M., Stanger, N., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. (2015). What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6423-6454.

Callaghan, A., McCombe, G., Harrold, A., McMeel, C., Mills, G., Moore-Cherry, N., & Cullen, W. (2021). The impact of green spaces on mental health in urban settings: a scoping review. Journal of mental health (Abingdon, England), 30(2), 179-193.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2009). Improving the health of Canadians: Exploring Positive Mental health. Author.

Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L., & Zelenski, J. M. (2014). The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1-15, Article 976.

Capio, C. M., Sit, C. H. P., & Abernethy, B. (2014). Physical Well-Being. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer Netherlands. 4805-4807.

Chevalier, G. (2015). The Effect of Grounding the Human Body on Mood. Psychological Reports, 116(2), 534-542.

Cicognani, E. (2014). Social Well-Being. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer Netherlands. 6193-6197.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cooley, S. J., Jones, C. R., Kurtz, A., & Robertson, N. (2020). ‘Into the Wild’: A meta-synthesis of talking therapy in natural outdoor spaces. Clinical psychology review, 77, 101841-101841.

Coventry, P. A., Brown, J. E., Pervin, J., Brabyn, S., Pateman, R., Breedvelt, J., Gilbody, S., Stancliffe, R., McEachan, R., & White, P. L. (2021). Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine – Population Health, 16, 1-15, Article 100934.

Diener, E. (2009). Subjective Well-Being. In E. Diener (Ed.), The Science of Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener (Vol. 37 – Social Indicators of Research Series). Springer. 11-58.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276-302.

Fang, B.-B., Lu, F. J. H., Gill, D. L., Liu, S. H., Chyi, T., & Chen, B. (2021). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Outdoor Education Programs on Adolescents’ Self-Efficacy. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 128(5), 1932-1958.

Farrace, S., Cenni, G., Casagrande, B., Barbarito, B., & Peri, A. (1999). Endocrine and Psychophysiological Aspects of Human Adaptation to the Extreme. Physiology and Behavior, 66(4), 613-620.

Farrace, S., Ferrara, M., De Angelis, C., Trezza, R., Cenni, P., Peri, A., Casagrande, M., & De Gennaro, L. (2003). Reduced sympathetic outflow and adrenal secretory activity during a 40-day stay in the Antarctic. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 49(1), 17-27.

Ferrell, A. D. (2017). A Meta-Analysis of Social Emotional Learning Outcomes in Challenge Course Programs (Publication Number 10269688) [PhD, University of Colorado]. Boulder, CO.

Fleischer, C., Doebler, P., Bürkner, P. C., & Holling, H. (2017). Adventure Therapy Effects on Self-Concept: A Meta-Analysis. PsyArXiv (preprint), 1-53.

Fyfe-Johnson, A. L., Hazlehurst, M. F., Perrins, S. P., Bratman, G. N., Thomas, R., Garrett, K. A., Hafferty, K. R., Cullaz, T. M., Marcuse, E. K., & Tandon, P. S. (2021). Nature and Children’s Health: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics, 148(4), 72-94.

Gatersleben, B., & Andrews, M. (2013). When walking in nature is not restorative—The role of prospect and refuge. Health and Place, 20(1), 91-101.

George, J. T. (2011). Efficacy of Outdoor Behaviour Healthcare (OBH) for adolescent populations: A meta-analysis [PhD, University of Indianapolis]. Indianapolis, IN.

Georgiou, M., Morison, G., Smith, N., Tieges, Z., & Chastin, S. (2021). Mechanisms of impact of blue spaces on human health: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 1-41.

Gillis, H. L., & Speelman, E. (2008). Are challenge (ropes) courses an effective tool? A meta-analysis. Journal of Experiential Education, 31(2), 111-135.

Gillis, H. L., Speelman, E., Linville, N., Bailey, E., Kalle, A., Oglesbee, N., Sandlin, J., Thompson, L., & Jensen, J. (2016). Meta-analysis of Treatment Outcomes Measured by the Y-OQ and Y-OQ-SR Comparing Wilderness and Non-wilderness Treatment Programs. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(6), 851-863.

Gray, C., Gibbons, R., Larouche, R., Sandseter, E., Bienenstock, A., Brussoni, M., Chabot, G., Herrington, S., Janssen, I., Pickett, W., Power, M., Stanger, N., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. (2015). What Is the Relationship between Outdoor Time and Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Physical Fitness in Children? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6455-6474.

Grouzet, F. M. E., & Lee, E. S. (2014). Ecological Well-Being. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer Netherlands. 1784-1787.

Hans, T. A. (2000). A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Adventure Programming on Locus of Control. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 30(1), 33-60.

Hanson, S., & Jones, A. (2015). Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 0, 1-7.

Harper, N., Rose, K., & Segal, D. (2019). Nature-based therapy: A practitioner’s guide to working outdoors with children, youth, and families. New Society Publishers.

Harrison, S., Kivuti-Bitok, L., Macmillan, A., & Priest, P. (2019). EcoHealth and One Health: A theory-focused review in response to calls for convergence. Environment International, 132, 1-15.

Hattie, J. M., Marsh, H. W., Neill, J. T., & Richards, G. E. (1997). Adventure education and Outward Bound: Out-of-class experiences that make a lasting difference. Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 43-87.

Holland, W. H., Powell, R. B., Thomsen, J. M., & Monz, C. A. (2018). A Systematic Review of the Psychological, Social, and Educational Outcomes Associated with Participation in Wildland Recreational Activities. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 10(3), 197-225.

Houlden, V., Weich, S., Porto De Albuquerque, J., Jarvis, S., & Rees, K. (2018). The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 13(9, e0203000), 1-35.

Husk, K., Lovell, R., Cooper, C., Stahl-Timmins, W., & Garside, R. (2016). Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: a review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(5), 1-256, Article Cd010351.

Jabbar, M., Yusoff, M. M., & Shafie, A. (2021). Assessing the role of urban green spaces for human well-being: a systematic review. GeoJournal, 87. 1-19.

Jackson, J., & Heshka, J. (2011). Managing risk: Systems planning for outdoor adventure programs. Direct Bearing Inc.

Johnstone, A., Martin, A., Cordovil, R., Fjørtoft, I., Iivonen, S., Jidovtseff, B., Lopes, F., Reilly, J. J., Thomson, H., Wells, V., & McCrorie, P. (2022). Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Social, Emotional and Cognitive Development: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 1-30.

Jordan, M., & Hinds, J. (2016). Ecotherapy: Theory, research and practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Joshanloo, M. (2016). Revisiting the Empirical Distinction Between Hedonic and Eudaimonic Aspects of Well-Being Using Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 2023-2036.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social Well-Being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(2), 121-140.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2010). The next steps in the promotion and protection of positive mental health. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 42(3), 17-28.

Kotera, Y., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2022). Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 337-361.

Laidlaw, J. S. (2000). A meta-analysis of outdoor education programs [DEd, University of Northern Colorado]. Greeley, CO.

Langelier, M.-È., Pétrin-Derosiers, C., & Bradette, I. (2023). Nature Rx. In S. Priest, S. D. Ritchie, & H. Ghadry (Eds.), Outdoor Learning in Canada. Open Resource Textbook. Retrieved from http://olic.ca

Li, D., Menotti, T., Ding, Y., & Wells, N. M. (2021). Life course nature exposure and mental health outcomes: a systematic review and future directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 1-28.

Li, H., Zhang, X., Bi, S., Cao, Y., & Zhang, G. (2022). Psychological benefits of green exercise in wild or urban greenspaces: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 68, 1-8.

Manning, M., & Fleming, C. (2019). The complexity of measuring Indigenous wellbeing. In Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Wellbeing. Routledge. 1-2.

Marsh, P. E. (1999). What Does Camp Do for Kids? A Meta-Analysis of the Influence of organized Camping Experience on the Self Constructs of Youth [MSc, Indiana University]. Bloomington, IN.

Mazurek Melynyk, B., & Neale, S. (Eds.). (2018). 9 Dimensions of Wellness: Evidence-Based Tactics for Optimizing your Health and Well-being. The Ohio State University.

McCormick, R. (2017). Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-being of Children: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 37, 3-7.

McMahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2015). The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 507-519.

Menardo, E., Brondino, M., Hall, R., & Pasini, M. (2021). Restorativeness in Natural and Urban Environments: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Reports, 124(2), 417-437.

Moeller, C., King, N., Burr, V., Gibbs, G. R., & Gomersall, T. (2018). Nature-based interventions in institutional and organisational settings: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 28(3), 293-305.

Montoya, A. L., & Summers, L. L. (2021). 8 dimensions of wellness for educators. The Learning Professional, 42(1), 49-62.

Müller, E., Pröller, P., Ferreira-Briza, F., Aglas, L., & Stöggl, T. (2019). Effectiveness of Grounded Sleeping on Recovery After Intensive Eccentric Muscle Loading. Frontiers in Physiology, 10. 534-542.

Parkes, M., Waltner-Toews, D., & Horwitz, P. (2014). Ecohealth. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer Netherlands. 1770-1774.

Parsons, J. (2020). Global and Planetary Health. In W. Leal Filho, T. Wall, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, & P. G. Özuyar (Eds.), Good Health and Well-Being. Springer International Publishing. 225-236.

Peterson, M., & Vann, R. J. (2014). Spirituality, Religiosity, and QOL. In A. C. Micholas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research.

Pierskalla, C. D., Lee, M. E., Stein, T. V., Anderson, D. H., & Nickerson, R. (2004). Understanding Relationships Among Recreation Opportunities: A Meta-Analysis of Nine Studies. Leisure Sciences, 26(2), 163-180.

Priest, S. (2020). Toward Establishing Indications and Contraindications in Outdoor Therapies. Canadian Outdoor Therapy and Healthcare. Retrieved from http://coth.ca/

Priest, S. (2023). Introduction: What is Outdoor Learning? In S. Priest, S. D. Ritchie, & D. Scott (Eds.), Outdoor Learning in Canada. Open Resource Textbook. Retrieved from http://olic.ca

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3), 1145-1167.

Rahimi-Ardabili, H., Astell-Burt, T., Nguyen, P.-Y., Zhang, J., Jiang, Y., Dong, G.-H., & Feng, X. (2021). Green space and health in mainland China: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 1-22.

Ritchie, S. D., D’Angelo, J., & Priest, S. (2022). How to Promote Ecohealth. Assoociation of Experiential Education. AEE CHIP-7. https://www.aee.org/chip

Ritchie, S. D., Wabano, M. J., Corbiere, R. G., Restoule, B., Russell, K., & Young, N. L. (2015). Connecting to the Good Life through Outdoor Adventure Leadership Experiences. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1-21.

Roberts, A., Hinds, J., & Camic, P. M. (2020). Nature activities and wellbeing in children and young people: A systematic literature review. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(4), 298-318.

Roszak, T., Gomes, M. E., & Kanner, A. D. (1995). Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind. Sierra Club Books.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727.

Sharma-Brymer, V., & Brymer, E. (2020). Flourishing and Eudaimonic Well-Being. In W. Leal Filho, T. Wall, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, & P. G. Özuyar (Eds.), Good Health and Well-Being. Springer International Publishing. 205-214.

Shek, D. T. L. (2014). Spirituality, Overview. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 6289-6295). Springer Netherlands. 6289-6294.

Stevenson, M. P., Schilhab, T., & Bentsen, P. (2018). Attention Restoration Theory II: a systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part B, Critical Reviews, 21(4), 227-268.

Stoewen, D. L. (2017). Dimensions of wellness: Change your habits, change your life. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne, 58(8), 861-862.

Swarbick, P. (2015). Wellness in 8 Dimensions. I. Collaborative Support Programs of NJ. Retrieved from https://cspnj.org/wellness-resource/

Thompson Coon, J., Boddy, K., Stein, K., Whear, R., Barton, J., & Depledge, M. H. (2011). Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(5), 1761-1772.

Tillmann, S., Tobin, D., Avison, W., & Gilliland, J. (2018). Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(10), 958-966.

Truelove, S., Bruijns, B. A., Vanderloo, L. M., O’Brien, K. T., Johnson, A. M., & Tucker, P. (2018). Physical activity and sedentary time during childcare outdoor play sessions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive medicine, 108, 74-85.

Walker, D. A., & Pearman, D. (2009). Therapeutic recreation camps: an effective intervention for children and young people with chronic illness? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94(5), 401-406.

Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., & Abrahamse, W. (2020). Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conservation Biology, 34(1), 180-193.

Wilson, S. J., & Lipsey, M. W. (2000). Wilderness Challenge Programs for Delinquent Youth: A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Evaluations. Evaluation and Program Planning, 23(1), 1-12.

Wolf, K. L., Lam, S. T., McKeen, J. K., Richardson, G. R. A., van den Bosch, M., & Bardekjian, A. C. (2020). Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 1-30.

World Health Organization. (2022). Mental Health. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

World Health Organization. (1948). Definition of Health. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution

Yadeun-Antuñano, M. (2020). Indigenous Perspectives of Wellbeing: Living a Good Life. In W. Leal Filho, T. Wall, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, & P. G. Özuyar (Eds.), Good Health and Well-Being (pp. 436-448). Springer International Publishing.

Yao, W., Zhang, X., & Gong, Q. (2021). The Effect of Exposure to The Natural Environment on Stress Reduction: A Meta-Analysis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 57, 1-12.

Yen, H.-Y., Chiu, H.-L., & Huang, H.-Y. (2021). Green and Blue Physical Activity for Quality Of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Landscape and Urban Planning, 212, 1-9.

Yuan, Y., Huang, F., Lin, F., Zhu, P., & Zhu, P. (2021). Green space exposure on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(7), 1783-1797.

Zhang, Y., Mavoa, S., Zhao, J., Raphael, D., & Smith, M. (2020). The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 1-26.

Zhang, G., Poulsen, D. V., Lygum, V. L., Corazon, S. S., Gramkow, M. C., & Stigsdotter, U. K. (2017). Health-Promoting Nature Access for People with Mobility Impairments: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 1-19.

Zinsstag, J., Schelling, E., Waltner-Toews, D., & Tanner, M. (2011). From “one medicine” to “one health” and systemic approaches to health and well-being. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 101(3), 148-156.