5 A Beautiful Messy Process: Outdoor Education in Canada

Morten Asfeldt

Author’s Note: This chapter is an edited and updated version of Asfeldt, M. (2021). A beautiful messy process: Outdoor education in Canada. Pathways: The Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education, 33(2), 4–17.

Outdoor education saved my life. Ok, that is an overstatement. However, saying that outdoor education (OE) changed and inspired my life is accurate. My first OE course was a month-long course in May 1981. I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I needed 3 credits to finish high-school and at the time I was attending Camrose Lutheran College which offered Grade 12 and the first two years of university. Physical Education 30 and university OE courses were taught by Dr. Garry “Gibber” Gibson and he offered me Physical Education 30 credits for completing this month-long university OE course. This sounded like a great deal to me and, as they say, the rest is history. By the end of May 1981–inspired by a remarkable group experience, new insights and perspectives on the natural world, and a great sense of confidence–my personal and professional OE journey had begun. In the past 40 years I have seen and felt the many benefits of OE as both a student and instructor.

During my nearly 30-year academic career, I have watched as universities have “discovered” active, hands-on, and group-and place-based teaching where students are more directly involved in the learning process and where instructors make connections between course content course and students’ everyday lives. As I have watched the trend for improved teaching and learning in universities unfold, I have often wondered how it could be that universities and colleges are only now “discovering” that an active classroom or outdoor space where students are interacting and engaged is a new and innovative idea? For outdoor educators, and many other educators, active engaged learning has always been our modus operandi and my guess is that most outdoor educators have never considered their practice new or innovative. Rather, I imagine most have known deep in their teaching souls that the traditions and practices of OE are just plain-old-good-teaching (Raffan, 1996).

This observation coupled with my ongoing professional struggle of justifying my OE teaching practices and wrestling for resources to support my OE courses–which, ironically, are well aligned with the emerging priorities and stated goals of universities and colleges in terms of these new active and innovative pedagogical practices and learning outcomes–led a colleague and I to conduct a nation-wide study of OE in Canada. The goals of this study were to identify the guiding philosophies, central goals, and distinguishing characteristics of OE in Canada with the hope of providing a foundation for a deeper understanding of Canadian OE in order to enhance the delivery of OE. We have published findings from our study in Purc-Stephenson, et al., (2019), Asfeldt et al., (2020), Asfeldt et al., (2022a), and Asfeldt et al., (2022b).

In short, the findings of our larger study demonstrate that outdoor educators are a committed and passionate group who are educating and inspiring students guided by well-grounded pedagogical practices. In Asfeldt et al., 2020 we write: “OE in Canada is grounded in experiential learning outdoors that link academic disciplines, and includes the added benefit of helping students make connections with the land, its people, and our past” (p. 11). In Asfeldt et al., (2022a) we state that “the holistic and integrated nature of OE is well suited to prepare children and youth for the challenges of living well in the 21st century that are well aligned with the purpose and mission of K-12 education in Canada” (p. 15). And finally, in Asfeldt et al., (2022b), we claim that “OE commonly provides the type of engaged, innovative, active, and experiential group-and place-based learning that facilitates a wide range of learning objectives that colleges and universities identify as priorities” (p. 306). In many ways, OE is ahead of emerging pedagogical trends that promotes active and innovative learning.

In this chapter, I will share our findings and hope the findings affirm the good work that outdoor educators are doing and have been doing for decades, as have talented and committed educators across many disciplines. In addition, I hope these findings well serve as evidence to assist in promoting a deeper understanding of the value of outdoor education to colleagues, administrators, governments, and other stakeholders in order to help camps, K-12 schools, and colleges and universities achieve their educational visions while preparing students to live purposeful and ethical lives.

Overview of the Study

If you are interested in the details of our methodology and research process, please read Asfeldt et al., (2020), Asfeldt et al., (2022a), and Asfeldt et al., (2022b). Here, I will provide the basics. First, we wanted to sample programs from across Canada. One of our goals was to see if a distinctly “Canadian Way” or “Ways” of OE might emerge. Second, we knew we had to limit our study or it would have become unmanageable. Therefore, we choose to focus on programs in summer camps, K-12, and post-secondary OE sectors. Third, we wanted to include some site-visits and in-person interviews knowing these would provide rich data that a survey just can’t provide. Fourth, while we wanted to include site-visits and interviews, we also wanted much broader participation than site-visits and interviews allowed. Therefore, after a thorough literature review of the Canadian OE literature (Purc-Stephenson, et al., 2019) we conducted 22 site visits and interviews (six summer camps, ten K-12 programs, five post-secondary programs, and one College of General and Professional Teaching [CEGEP] in Quebec) (see Asfeldt et al., 2020). Based on these interviews, we created an online survey that resulted in 93 responses from summer camps, 100 responses from K-12 programs, and 22 responses from post-secondary programs for a total of 215 completed surveys. The site-visits and interviews as well as the surveys focused on three specific aspects of each program: (1) the underlying program values and philosophies, (2) the central goals of the program, and (3) the common activities included in each program.

Site Visits and Interview Findings

The findings from our site visits and interviews point to OE being a method of teaching that addresses important educational, environmental, and social challenges and issues that Canada and the world face today. In 1972, John Passmore conducted a nation-wide study of OE in Canada and he concluded that:

Outdoor environmental education is certainly not the answer to all our educational problems. But there is growing recognition that it is a method of teaching that can add that other important “R” to every subject on the curriculum – relevance in what we teach about the world in which our young people live (p. 61).

Our findings point to Passmore’s insights being as true today as they were in 1972: OE continues to be a sound educational practice that is guided by robust pedagogical philosophies and results in valuable and relevant learning outcomes.

Philosophies

Based on our site visits and interviews, we identified five themes that represent the most common philosophies that drive OE programs in Canada. We titled these themes:

- Influential Founders,

- Hands-On Experiential Learning,

- Holistic and Integrated Learning,

- Journey through the Land, and

- Religion and Spirituality.

OE programs in Canada are often initiated by influential founders such as an inspired and passionate teacher (or group of teachers) who have experienced the benefits of OE and recognized that many of those benefits aren’t being realized within the limits of traditional disciplines, classrooms, and school schedules. Now, having said that, I want to be clear that there are many inspired and passionate teachers that are doing great work within these limits and in no way are we suggesting that OE is the only solution to the challenges of education. Nevertheless, OE does address many challenges of education and the influential founders that people described during the interviews used their experience and visions for OE to make a unique contribution to lighting a learning fire in their students. Often, the people we interviewed spoke of how an influential founder was once their teacher or mentor and that they were so inspired by their work that they have now devoted their teaching life to carrying on that founder’s vision. Sadly, in many cases, once a founder retired, OE programs were often discontinued because there was no one in place to carry on the program. This points to a difference between OE programs and those of traditional disciplines such as math, biology, or English, which are well-established in schools and universities and when a teacher or faculty member retires, it is relatively easy to hire a replacement. However, because OE sits on the margins of many school and post-secondary curricula, without a passionate and inspired advocate, OE is more likely to be set adrift. Interestingly, during our site visits, we consistently observed that most OE programs at K-12 and post-secondary institutions worked from basement rooms, repurposed closets, and old garages and sheds in far corners of school property. Not once did we observe a purpose-built OE space. This lack of dedicated space suggests that OE continues to exist on the margins of Canadian K-12 and post-secondary education.

Not surprisingly, the theme of hands-on experiential learning was one of the dominant themes describing the underlying philosophies of OE programs. Just about all the people we interviewed talked about the importance of hands-on experiential learning which they described as getting students out of the classroom and engaged in an active form of learning. In addition, those we interviewed spoke of their strong belief that hands-on learning was central to their program because it promoted deeper understanding of the course content and aided in making the content interesting and relevant. A notable observation was that not very many teachers or OE leaders connected hands-on experiential learning to any particular educational philosopher or theoretical foundation such as that of John Dewey (Experiential Education) or Jack Mezirow (Transformational Learning). Generally, we came away from our interviews with the impression that teachers and leaders knew intuitively that hands-on experiential learning just made sense; it was an obvious way of teaching that didn’t require an identifiable or articulated academic educational philosophy or theoretical foundation to implement. This was a bit surprising and makes us wonder what OE and other educational practices might look like if teachers and leaders had a greater understanding of some of the philosophies and theories that are often linked with OE?

The notion of OE as a means of facilitating holistic and integrated learning was also a well-defined theme. In essence, teachers and leaders believe that one of the strengths of OE is that it blurs the boundaries of traditional academic disciplines and helps students recognize the interconnected nature of life and the world. For example, OE programs can help students link knowledge from physics and physical education by using knowledge from both disciplines as they learn to paddle a canoe. Students can also link knowledge from history and literature to enrich a river or snowshoe journey by bringing the stories of the past and present alive in the land, the trees, and the water. And, the knowledge of biology, chemistry, and environmental studies can be linked with social studies as students study the impact of pollution and environmental reclamation by visiting local spaces as well as during remote travel experiences. One of our interviewees said it eloquently when they described their program as a process “where academics matter, relationships matter, the environment matters, and it’s all tied together in this beautiful experience”.

Journeying through the land emerged as an important element of many programs. That is, teachers and leaders believed that self-propelled small group travel experiences provide rich learning. It is easy to see that a travel experience in remote or even local space, is a natural form of hands-on experiential holistic integrated learning. It is a beautiful synergy. Further, teachers and leaders felt that just spending time in nature was itself an important experience that in some ways needed no further structure or facilitation by the teacher: nature itself is a great teacher. However, the travel experience was linked to facilitating many of the learning outcomes that I will describe later but include personal and social development and as a means for learning about Canadian history and culture and particularly about Indigenous people. Some felt that the self-propelled travel experience is a quintessential Canadian experience.

Philosophies and values rooted in religious and spiritual traditions also shape OE in Canada. For some, traditional Christian values drive programs yet for most programs, the term “spirituality” was used to describe the idea of the world and life having a mysterious element that isn’t rooted in a defined religious tradition. Regardless, this again points to OE being a form of holistic integrated learning where many forms of knowing are encouraged. In contrast, traditional education is too often siloed into distinct disciplines in a manner that doesn’t reflect the complex (yet sometimes simple) and messy (but also beautiful) interconnections and realities of a student’s life and the world as they experience it.

Learning Goals

It is no surprise that OE programs have a variety of learning goals. OE is more than learning to paddle a canoe or light a fire or identify a specific bird song. These can all be important skills to learn but for the most part, they are not important on their own or in isolation. Rather, they are important activities that reflect the philosophies that guide OE programs and are a means of achieving specific program learning goals. Again, there is a purpose to what might appear to be messy madness or aimless recreational learning. After considering all the learning goals described by our interviewees, we boiled them down into five themes:

- Building Community,

- Personal Growth,

- People and Place Consciousness,

- Environmental Stewardship, and

- Employability and Skill Development.

Here again we see the diverse interwoven nature of OE. Building community emerged as one of the primary goals of OE. The people we interviewed spoke passionately about the goal of promoting teamwork and fostering relationships within the groups they work with. Often, teachers and leaders expressed that they sense students today lack opportunities for genuine experiences of teamwork and honest relationships and that OE is one avenue for sharing the joy of community with students. It is easy to imagine a clear link between building community and the practice of self-propelled remote travel. That is, remote travel facilitates a sense of community as students are required to work collaboratively in most aspects of the travel experience as they work towards a common goal or in many cases, a variety of shared goals as reflected in the diverse range of learning goals linked to OE.

Using OE as a means for promoting personal growth is just as common as building community and there is a natural relationship between personal growth and being a part of a genuine community. Awareness of personal strengths and shortcomings often bubble to the surface when we are engaged in relevant and interesting mental and physical group challenges. This link between building community and personal growth through OE was acknowledged by many interviewees and point to some common roots of Canadian OE such as the Ontario summer camp tradition (Wall, 2009) which aimed to develop character as did the British tradition of Scouting and Outward Bound which have also both influenced OE in Canada. These early influences reflect the notion that “education is essentially a social process” (Dewey, 1938, p. 58) which is revealed today in the themes of building community and personal growth.

Enhancing people and place consciousness reflects the goal of teaching about a specific location, people, and their historical significance. As Henderson (2005) has so often said: “Every trail has a story.” Henderson’s point is that when we paddle a river or hike a trail, we are paddling a particular river and hiking a particular trail. These are not just anonymous undiscovered rivers and trails. Rather, these rivers and trails have unique and particular pasts and stories. Central to Henderson’s idea of “every trail has a story” is that to know these pasts and stories provides a much richer river and trail experience which presents an opportunity to understand Canadian history and culture, which is sometimes deeply troubling. However, understanding our troubled past that has resulted in generations of harm and broken relationships with Indigenous Canadians and resulted in many environmental abuses is an opportunity for deep learning. As Meerts-Brandsma et al., (2020) point out, OE is well positioned to address many such issues of privilege that need urgent attention.

Environmental stewardship also emerged as an important learning goal. Interviewees spoke particularly about the importance of educating students for sustainable futures and giving students the knowledge and skills for implementing sustainable practices in their daily lives. During expeditions, sustainable environmental camping and travel practices were commonly taught. The environmental concerns of the 1960s and 70s were a significant influence on the emergence of OE in Canada. OE continues to be a means for educating students about lingering concerns of the 1960s and 70s but also current issues particularly as we wrestle with accelerating climate change.

The final learning goal addressed issues related to preparing students for employability in outdoor related fields. This generally included a focus on skill development leading to certification in outdoor skills such as canoeing as well as safety training such as first-aid.

Activities

As a part of our interviews and site visits, we were interested in getting a sense of activities that are commonly included in OE programs. There is a long list. After combining all the activities that are included in summer camps, K-12, and post-secondary programs, we composed a list of 33 different activities. To better understand these activities, we funneled these 33 activities into seven broad categories: outdoor-living skills (e.g., cooking and fire-building); sport and recreation activities (e.g., canoeing and kayaking); work experience and certification (e.g., job shadowing and first aid training); environmental education activities (e.g., nature walks and birdwatching); games (e.g., group games for fun and to promote personal and social development); reflection (e.g., journaling and group discussions); and arts and crafts (e.g., paddle and moccasin making). On average, programs offer 14 different activities. The most common activities were those from the outdoor-living skills and sport and recreation categories.

Survey Findings

As mentioned earlier, once we completed the literature review and interview stages of this project, we created three unique surveys, one for each sector: summer camps, K-12 programs, and post-secondary programs. The goal of the surveys was to see how well our findings and themes from the interview stage mapped across Canada and across our three target sectors. While each survey collected data specific to each sector, they also collected data regarding guiding philosophies, central goals, and distinguishing activities. This allowed us to present data specific for each sector. Here I will present an overview. More in-depth research findings for K-12 programs can be found in Asfeldt et al., (2022a) and for post-secondary programs in Asfeldt et al., (2022b).

Philosophies

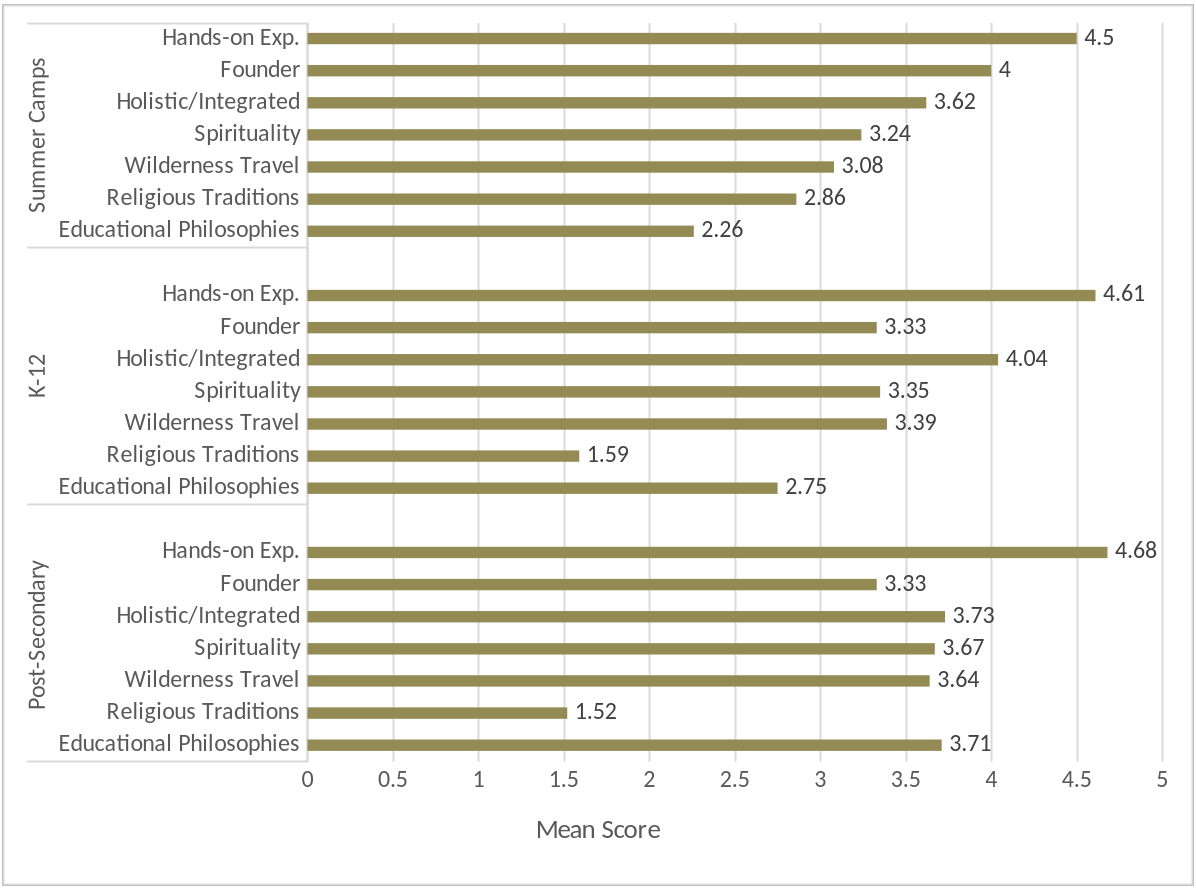

Figure 1 displays how summer camps, K-12, and post-secondary programs rated the influence of seven underlying philosophies and values. You will notice there are seven themes here rather than five as in the interviews. This is because we subdivided some of the original five themes in order to obtain a more nuanced understanding (i.e., we added educational philosophy, renamed journey through the land to self-propelled wilderness travel and split religion and spirituality into two distinct themes). Respondents were asked to rate how much they agreed or disagreed that a specific philosophy or value influences their programs. That is, the higher the mean rating of a particular philosophy or value, the more that philosophy shapes a program. For example, given our findings, a reasonable division would be low influence (0.00 to 2.5), neutral influence (2.6-3.5), and strong influence (3.6-5.0).

Overall, the pattern of influence remained much the same as that revealed through the interview study. For example, hands-on experiential learning, holistic integrated learning, and the impact of influential founders remained dominant. However, some sector differences exist. For example, summer camps are the least influenced by educational philosophies and have the strongest religious tradition influence. Given that many summer camps are supported by churches and other religious organizations, this finding makes sense.

Religious traditions have just about no influence in K-12 and post-secondary programs, yet spirituality does influence K-12 and post-secondary programs. This finding likely points to the fact that K-12 and post-secondary are often publicly funded and therefore have a broader approach to spirituality versus a specific denominational approach. Holistic integrated learning has the strongest influence in K-12 programs which supports the notion that OE is a common means for blurring the boundaries of traditional academic disciplines. The influence of ideas directly linked to specific educational philosophies is greatest in post-secondary programs. This is not surprising given that academics are typically more immersed in the academic literature where educational philosophies are more commonly discussed and examined.

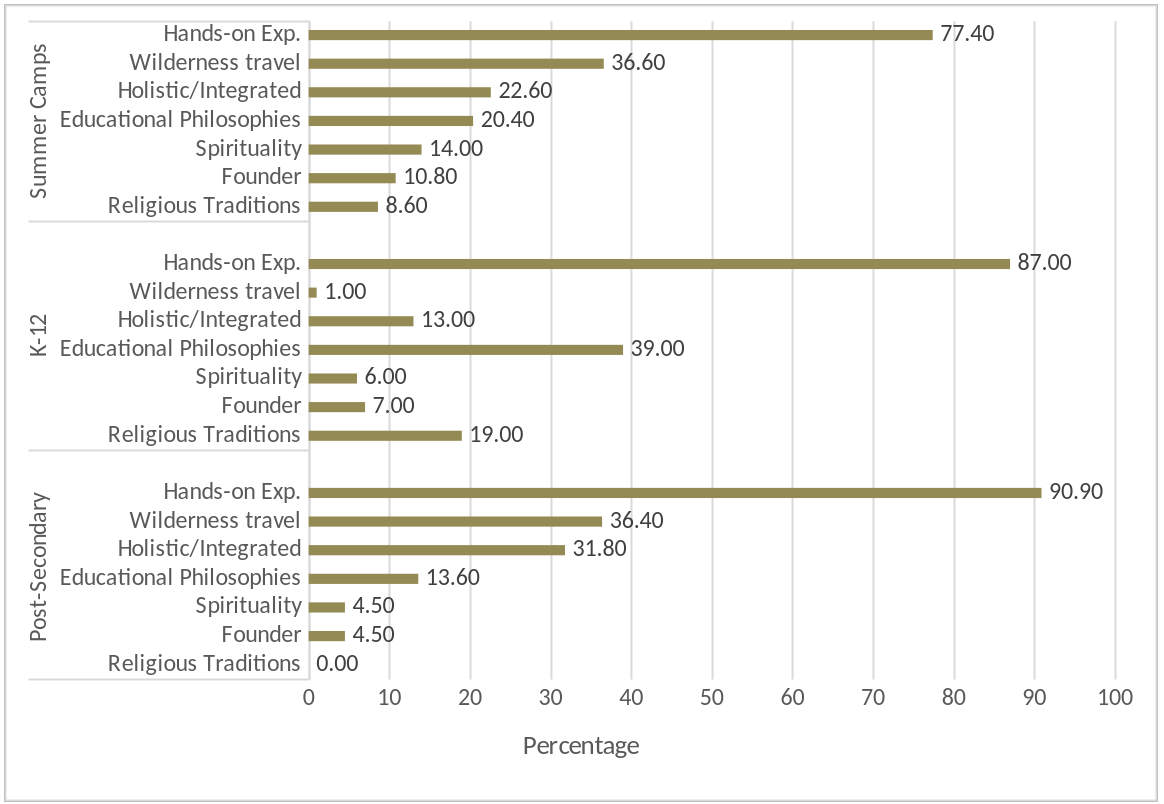

After asking respondents to rate the influence of these seven philosophies and values on their programs, we asked them to identify which two philosophies are most essential to their program philosophy (Figure 2). Greater variation among sectors was found for these data. However, hands-on experiential learning is clearly the most influential philosophy that drives programs across all three sectors. Given the recent push for more experiential learning in K-12 and particularly post-secondary education in Canada, this finding points to OE being ahead of emerging pedagogical trends; OE is a leader of the pack, one might say. Other notable findings include affirmation of the strong influence of religious traditions in summer camps and holistic integrated learning in K-12 programs. Self-propelled travel was most influential in post-secondary programs where influential founders had the least influence.

Learning Goals

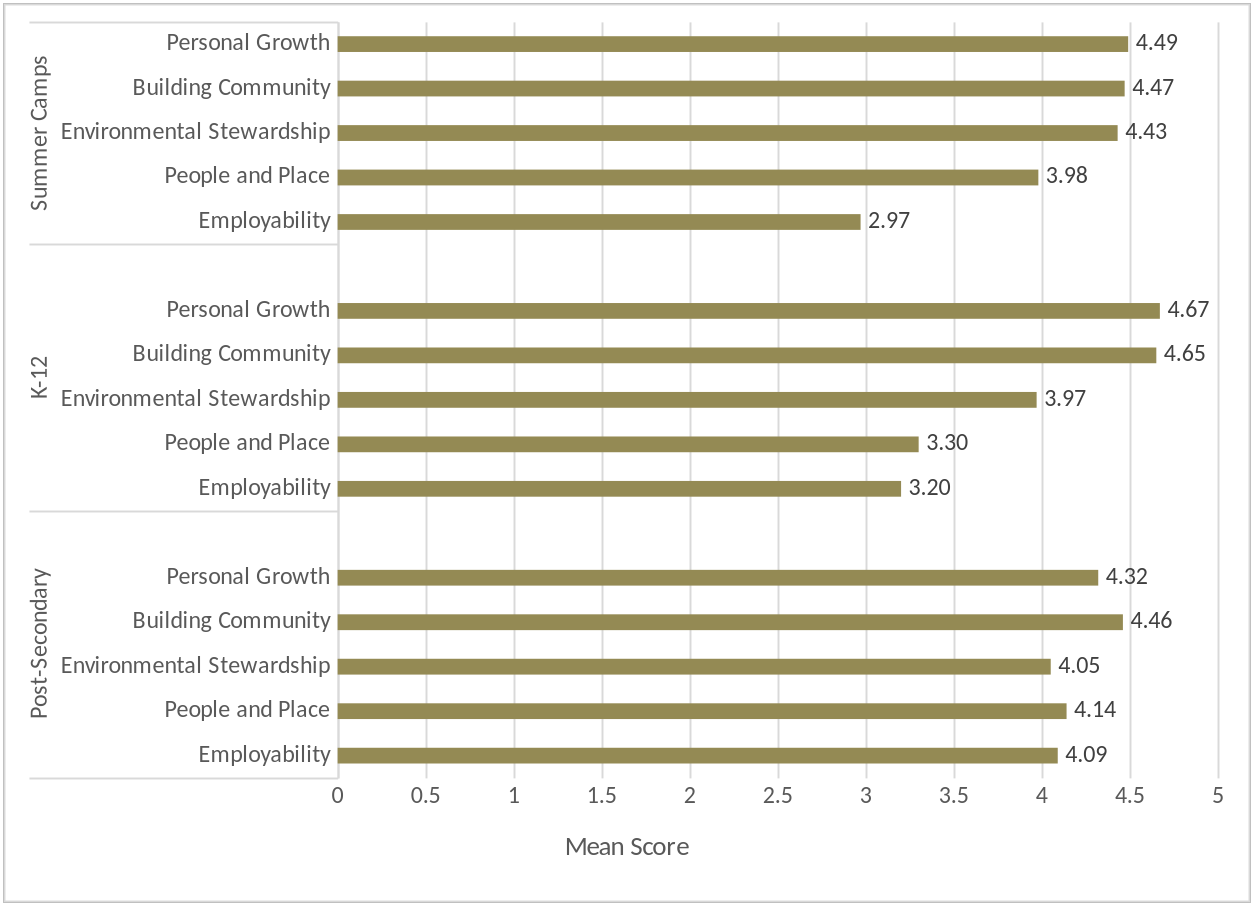

The data regarding learning goals reveal that OE programs generally include a number of important goals. The inclusion of a range of learning goals makes sense given the importance of OE as a holistic integrated form of learning (Figure 3) where the boundaries of traditional disciplines are blurred in order to enable connections between these disciplines that reflect the reality of life as students experience it. This is well aligned with the Deweyian idea that “education, […], is a process of living and not preparation for future living” (Dewey, 1981, p. 445) which is one of Dewey’s key ideas that shapes his educational philosophy of experiential education. Dewey was a leader of progressive education movement in North America in the early 20th century and, in the academic world, is often seen as one of the founders of experiential education which has shaped modern day outdoor and adventure education.

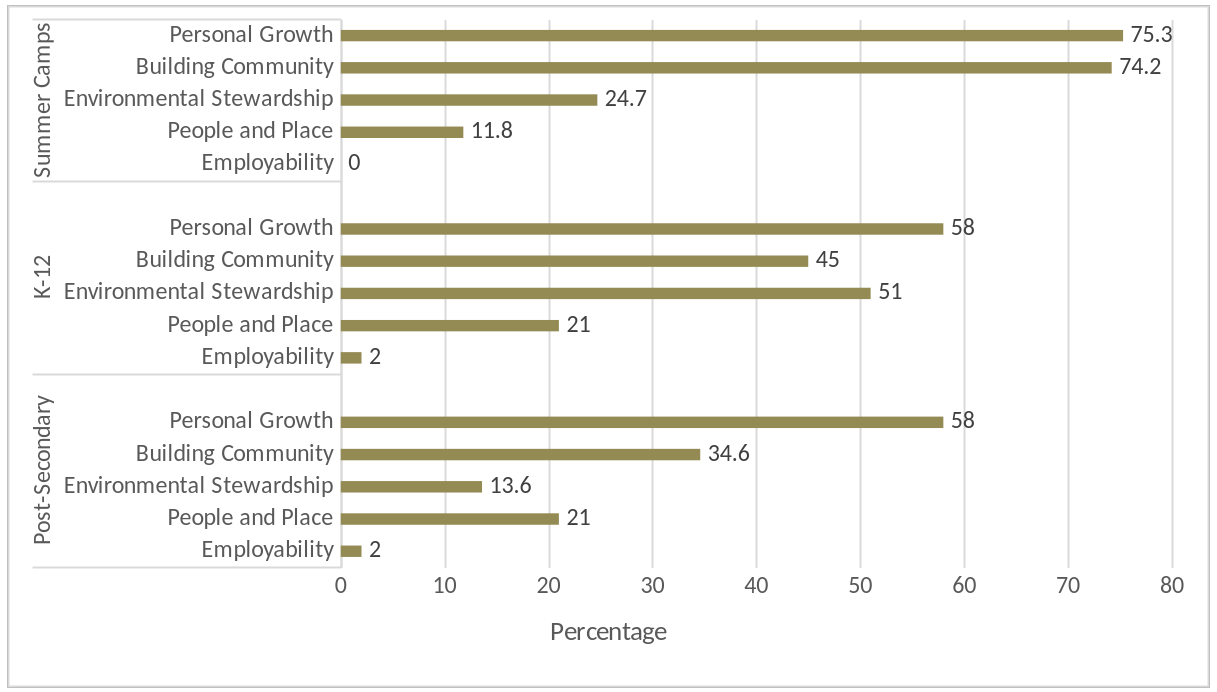

As with philosophies and values, we asked respondents to identify the two most important learning goals from our list (Figure 4). Again, some variance among sectors was found, but overall, the two most important OE learning goals are personal growth and building community. This may point to outdoor educators recognizing that the social process of learning is critical to effective education. That is, as my mentor Gibson often said: “You aren’t teaching outdoor education; you are teaching people” (personal communication, 1992). From this perspective, these findings may point to outdoor educators recognizing that a critical role of education is to help students learn about themselves and that creating a safe and affirming community setting facilitates not only learning about themselves but also provides a foundation for learning about, in this case, environmental stewardship and people and place consciousness. For certain, it appears that outdoor educators are more likely to see education as a transformational process versus a transactional process of knowledge transfer. A transactional process of knowledge transfer is one where the primary goal is to have students learn specific disciplinary content (e.g., numerical literacy) and little attention is paid to how that knowledge might impact, or transform, the students. In contrast, a transformational perspective aims to not only have students learn specific disciplinary knowledge but equally, to have the process of learning disciplinary knowledge change, or transform, the students’ understanding and perspective of themselves, others, and the world they live in. One might say that a transactional approach is a clean and neat efficient process while a transformational approach embraces the messy and unpredictable nature of learning that values effectiveness over efficiency (Asfeldt & Beames, 2017). From this perspective, OE is a beautiful messy process.

|

RANGE |

Summer Camps n=93 |

K-12 n=100 |

Post-Secondary n=22 |

|||

|

80-100% |

n=86, (92.5%) n=82, (88.2%) |

Campfires Games |

|

No activities reported. |

n=20 (90.9%) n=19 (86.4%) n=19 (86.4%) n=19 (86.4%) |

Camping Campfires Canoeing Hiking |

|

60-79% |

n=76, (81.7%) n=70, (75.3%) n=69, (74.2%) n=67, (72.0%) n=66, (71.0%) n=66, (71.0%) n=66, (71.0%) |

Canoeing Camping Archery Hiking Nature Studies Orienteering Swimming |

n=79 (79.0%) n=77 (77.0%) n=77 (77.0%) n=70 (70.0%) n=70 (70.0%) n=69 (69.0%) n=65 (65.0%) n=62 (62.0%) n=61 (61.0%) |

Camping Games Campfires Nature Studies Orienteering Hiking Cooking Snowshoeing Canoeing |

n=17 (77.3%) n=16 (72.7%) n=16 (72.7%) n=16 (72.7%) n=15 (68.2%) n=15 (68.2%) n=14 (63.6%) n=13 (59.1%) n=13 (59.1%) |

Journal Writing Safety Training Orienteering Nature Studies Cooking Snowshoeing Certification Climbing Skiing |

|

40-59% |

n=59, (63.4%) n=57, (61.3%) n=54, (58.1%) n=48, (51.6%) n=42, (45.2%) |

Climbing Ropes Service Learn Kayaking Cooking |

n=52 (52.0%) n=50 (50.0%) n=43 (43.0%) |

Journal Writing Skiing Climbing |

n=12 (54.5%) n=11 (50.0%) n=11 (50.0%) n=10 (45.5%) n=10 (45.5%) n=10 (45.5%) |

Kayaking Games Biking Solos Service Learn Work Exp |

|

20-39% |

n=36, (38.7%) n=35, (37.6%) n=35, (37.6%) n=32, (34.4%) n=28, (30.1%) n=25, (26.9%) n=23, (24.7%) n=19, (20.4%) n=19, (20.4%) |

Journal Writing Biking Work Exp. Safety Training Snowshoeing Certification Fishing Gardening Horse Riding |

n=37 (37.0%) n=36 (36.0%) n=36 (36.0%) n=35 (35.0%) n=32 (32.0%) n=31 (31.0%) n=30 (30.0%) n=29 (29.0%) n=24 (24.0%) n=24 (24.0%) n=21 (21.0%) n=20 (20.0%) |

Archery Safety Training Certification Service Learn Biking Swimming Ropes Fishing Kayaking Gardening Skating Winter Tenting |

n=8 (31.8%) n=6 (27.3%) n=5 (22.7%) |

Ropes Winter Tenting Fishing |

|

0-19% |

n=17, (18.3%) n=14, (15.1%) n=14, (15.1%) n=13, (14.0%) n=8, (8.6%) n=6, (6.5%) n=2, (2.2%) n=1, (1.1%) n=1, (1.1%) n=0, (0%) |

Skiing Skating Yoga Solos Rafting Caving Winter Tenting Dogsledding Hunting Indigenous Act. |

n=19 (19.0%) n=17 (17.0%) n=13 (13.0%) n=8 (8.0%) n=8 (8.0%) n=7 (7.0%) n=6 (6.0%) n=5 (5.0%) n=0 (0%) |

Work Exp. Yoga Solos Horse Riding Hunting Rafting Dogsledding Caving Indigenous Act. |

n=4 (18.2%) n=4 (18.2%) n=3 (13.6%) n=3 (13.6%) n=2 (9.1%) n=1 (4.5%) n=1 (4.5%) n=0 (0%) n=0 (0%) n=0 (0%) n=0 (0%) |

Rafting Swimming Dogsledding Gardening Hunting Skating Yoga Horse Riding Caving Archery Indigenous Act. |

Activities

In order to understand the breadth and frequency of activities offered as a part of OE programs, we asked two questions. First, we asked respondents to identify all the activities that are offered in their programs. Second, we asked them to identify the three most common activities in their programs. Table 1 shows the number of programs and percentage of the sector that offer each of the 33 activities from our list which was developed based on the interviews and site visits. A total of 86 out of 93 (92.5%) summer camps included campfires, 79 of 100 (79%) K-12 programs involved camping, and 20 of 22 (90.9%) post-secondary programs offered camping.

|

SECTOR |

n (%) |

ACTIVITY |

|

Summer Camps n=93 |

n=27 (29.0) |

Ropes Course |

|

n=25 (26.9) |

Canoeing |

|

|

n=24 (25.8) |

Swimming |

|

|

n=20 (21.5) |

Climbing |

|

|

n=18 (19.4) |

Archery |

|

|

K-12 n=100 |

n=40 (40.0) |

Hiking |

|

n=27 (27.0) |

Canoeing |

|

|

n=24 (24.0) |

Camping |

|

|

n=23 (23.0) |

Nature Studies |

|

|

n=18 (18.0) |

Games |

|

|

Post-Secondary n=22 |

n=10 (45.5) |

Canoeing |

|

n=7 (31.8) |

Camping |

|

|

n=5 (22.7) |

Hiking |

|

|

n=4 (18.5) |

Skiing |

|

|

n=3 (13.6) |

Kayaking |

Table 2 identifies the most common activities offered by programs in each sector. Ropes courses were identified as one of the three most common summer camp activities by 27 of 93 (29%) summer camp respondents. Similarly, hiking was identified by 40 of 100 (40%) of K-12 programs as one of the three most common activities. And, 10 of 22 (45.5%) post-secondary programs identified canoeing as one of the three most common activities in their programs.

One particularly interesting finding regarding activities is that no respondents identified including Indigenous activities in their programs. This needs further investigation to better understand. We added Indigenous activities to our list of activities because many programs identified Indigenous learning as a program learning goal in the interview stage. One explanation for this finding may be that Indigenous learning is an emerging learning goal and not yet tied to a particular activity. Alternatively, it could be that our expectation that Indigenous learning goals would be directly tied to an activity is incorrect. Rather, it could be that the Indigenous learning goal is woven throughout all aspects of the program and therefore not linked to a particular activity.

Key Takeaways

While these findings regarding philosophies, learning goals, and activities are interesting on their own, our primary goal for this project is to deepen the understanding of OE in Canada so that we might enhance the delivery of OE. Therefore, here are some key takeaways that we hope are helpful in achieving that goal. Those of you from different sectors and unique political and cultural settings may have additional and perhaps different takeaways. If you do, I encourage you to share them in order to continue the development and understanding of OE in Canada.

Undervalued and Misunderstood

Dyment and Potter (2021), writing about post-secondary OE internationally, claim that one reason OE programs are often abandoned and poorly supported is because OE is frequently undervalued and misunderstood. In addition, the authors suggest OE is often seen as lacking pedagogic rigor by non-OE colleagues and administrators. One of our interviewees described the educational philosophy of their program as “a mess of stuff!” Their point was that OE is not just one philosophy or one value or aimed at achieving one learning goal. Rather, OE is more akin to a synthesizing discipline and method that provides a more organic form of education that is messy and difficult to neatly describe and define but at the same time beautiful. As K-12 and post-secondary institutions continue the never-ending quest to improve student learning, the messy integrated interdisciplinary hands-on nature of OE that makes it so difficult to describe, define, and neatly package may, ironically, be one of OE’s primary strengths.

This strength can be an important model for how to educate our children and youth. However, it is much easier for administrators and governments to neatly package education into tidy disciplinary units with precisely identified learning outcomes that present well in vision and funding documents but perhaps don’t reflect the reality of how students learn best or how to prepare students for the challenges and complexities of the lives they are living. Therefore, one utility of this research is that it provides evidence of OE having well-grounded pedagogic roots in hands-on experiential learning that is holistic and integrated in nature and highlights that many OE programs are designed to achieve a variety of interdisciplinary learning goals. These philosophies and goals are well aligned with emerging pedagogies that aim to be more experiential and interdisciplinary, to develop social and emotional skills, and prepare students to creatively address pressing environmental and social issues. One suggestion for outdoor educators is to review the goals and missions of your provincial education ministries, local school boards, and individual colleges and universities and use this data to provide evidence for how OE can help these bodies achieve their stated goals and missions.

It is easy to imagine that some colleagues and administrators might perceive OE as pedagogically adrift because of the recreational nature of the primary activities associated with OE such as outdoor-living skills and sport and recreational activities. This perception is likely heightened because OE is not a well-established discipline such as English or History or other core disciplines. However, this research demonstrates that OE activities are more than enjoyable recreational activities. Rather, the activities of OE are intentionally used to achieve specific and important learning goals using active methods that enhance student engagement.

Discipline or Method

A debate has been going on in some OE circles about whether OE is a discipline or a method of teaching (Dyment and Potter, 2015; Potter and Dyment, 2016). On the one hand, it doesn’t matter. On the other hand, maybe it is critical. My sense is that outdoor educators have been trying for decades to distinguish OE as a discipline similar to traditional well-established disciplines. If the most important outcome of this debate is to provide children and youth with the types of learning opportunities that OE affords, perhaps we should consider framing OE as a method of teaching where we can achieve the goals of a wide variety of emerging and traditional disciplines. In this way, we are promoting an active innovative pedagogy that aligns with emerging trends, rather than continuing the battle to establish OE as a stand-alone discipline. This strategy has and is working in some places such as integrated high-school programs and a number of university programs.

As these findings reveal, Canada has no single template for OE. While there are similarities and common philosophies, learning goals, and activities, there is also great diversity. The notion of OE as a synthesizing method that is molded to each unique camp, K-12, and post-secondary setting (e.g., geographical, cultural, historical) may be a “Canadian Way.” In other words, a “Canadian Way” that is guided by the philosophies, learning goals and activities identified in the study, but at the same time, this “Canadian Way” is shaped and molded to local geographies, histories, and cultures which results in not one specific “Canadian Way” of OE but many “Canadian Ways.” From this perspective, to the untrained eye, OE might look like a messy process, while to the trained eye, it is a “beautiful messy process” with purpose. Therefore, it may be more accurate to situate OE as a method rather than a discipline as Passmore did in 1972.

Reconciliation, Racism, and Privilege

Canada and Canadians have made a commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians as reflected in the recent Truth and Reconciliation Report (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015). Considering the philosophies and values that drive OE coupled with OE’s common learning goals, OE is well positioned to address reconciliation as well as racism and privilege more generally. For example, having students work together in diverse groups during self-propelled remote travel experiences on traditional lands while learning about the history and culture of the travel route or local spaces is already contributing to the process of reconciliation. Engaging students in such hands-on experiences of diverse people and places can be a powerful learning experience. While this can be intimidating and challenging work, there are increasing resources being developed and available to assist us in this task. Here are some resources that have been helpful for me (Erickson & Wylie Krotz, 2021; Henderson & Blenkinsop, 2022; Lowen-Trudeau, 2014; Lowen-Trudeau, 2019; Meerts-Brandsma et al., 2020).

Revisiting Humility

Dyment and Potter (2021) encourage outdoor educators to be less humble. We need to believe in what we do and we need to be willing to advocate for support of our OE programs. This can be exhausting work. However, one clear observation from our interviews and site visits is that outdoor educators are a committed and passionate group of teachers and leaders who are providing profoundly meaningful experiences for students and campers. And, as we all know, there are easier ways to keep our jobs as teachers and faculty members than taking students on off-campus learning journeys. Furthermore, as I hope you have recognized, while some colleagues and administrators may undervalue our work and question the pedagogical substance of OE, this data tells a very different story. Outdoor educators are doing great work as many K-12 schools and universities are playing pedagogical catch-up as they aim to implement more experiential integrated learning that achieve interdisciplinary learning objectives. Of course, there is room for OE to improve, but we have been and continue to be on a good path!

Finally, I encourage you all to support your local, regional, national, and international OE and educational organizations in order to continue the development of an informed and united voice for OE. It is important that we are able to articulate the many benefits of OE and to demonstrate how OE can contribute to the achievement of the goals and missions of our camps, K-12 schools, and colleges and universities. There are many benefits beyond those revealed in this study. However, this research does provide additional words and evidence to support your program, inspire your teaching, and encourage you to remember that you are doing important work. OE is not the magic bullet that will solve all our educational challenges or address all our environmental or social issues. However, it has many strengths and benefits that can make an important contribution towards those goals.

References

Asfeldt, M., Purc-Stephenson, R., & Zimmerman, T. (2022a). Outdoor education in Canadian public schools: Connecting children and youth to people, place, and environment. Environment Education Research. 28(10), 1510-1526.

Asfeldt, M., Purc-Stephenson, R., & Zimmerman, T. (2022b). Outdoor Education in Canadian Post-Secondary Education: Common Philosophies, Goals, and Activities. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. 25(3), 311-312.

Asfeldt, M., Purc-Stephenson, R., Rawleigh, M., & Thackeray, S. (2020). Outdoor education in Canada: a qualitative investigation. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 21(4), 297-310.

Asfeldt, M. & Beames, S. (2017). Trusting the journey: Embracing the unpredictable and difficult to measure nature of wilderness educational expeditions. Journal of Experiential Education, 40(1), 72-86.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. MacMillan.

Dewey, J. (1981). My pedagogic creed. In McDermott, J. (Ed.), The philosophy of John Dewey (pp. 442-453). University of Chicago Press.

Dyment, J. E., & Potter, T. G. (2021). Overboard! The turbulent waters of outdoor education in neoliberal post-secondary contexts. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 24(1), 1–17.

Dyment, J. E., & Potter, T. G. (2015). Is outdoor education a discipline? Provocations and possibilities. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 15(3), 193–208.

Erickson, B. & Wylie Krotz, S. (Eds.). (2021). The politics of the canoe. University of Manitoba Press.

Henderson, B. (2005). Every trail has a story: Heritage travel in Canada. Dundurn.

Henderson, B. & Blenkinsop, S. (2022). Paddling pathways: Reflections from a changing landscape. Your Nickel’s Worth Publishing.

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2014). Considering ecological métissage: To blend or not to blend? Journal of Experiential Education, 37(4), 351-366.

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2019). From reticence to resistance: Understanding educators’ engagement with indigenous environmental issues in Canada. Environmental Education Research, 25(1), 62-64.

Meerts-Brandsma, L., Lackey, N. Q., & Warner, R. P. (2020). Unpacking Systems of Privilege: The Opportunity of Critical Reflection in Outdoor Adventure Education. Education Sciences, 10(11), 318.

Passmore, J. (1972). Outdoor education in Canada–1972. Canadian Education Association.

Potter, T. G., & Dyment, J. E. (2016). Is outdoor education a discipline? Insights, gaps and future directions. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1–14.

Purc-Stephenson, R. J., Rawleigh, M., Kemp, H., & Asfeldt, M. (2019). We are wilderness explorers: A review of outdoor education in Canada. Journal of Experiential Education, 42(4), 364–381.

Raffan, J. (1996). About boundaries: a personal reflection on 25 years of C.O.E.O. and outdoor education. Pathways: The Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education. 8(3). 4-11

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Canada’s Residential Schools: Reconciliation: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 6. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Wall, S. (2009). The nurture of nature: Childhood, antimodernism, and Ontario summer camps, 1920-55. University of British Columbia Press.