1.4 Typical Marketing Channels

The Alignment of B2B Marketing and the Game of Golf

Read the golf analogy about B2B Marketing at 6 Ways B2B Marketing & Golf Disciplines Coincide (barkb2b.com)

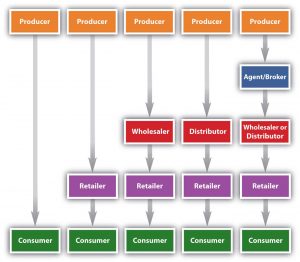

Figure 1.4.1 shows the typical channels in business-to-consumer (B2C) markets. As we explained, the shortest marketing channel consists of just two parties—a producer and a consumer. A channel such as this is a direct channel. By contrast, a channel that includes one or more intermediaries—say, a wholesaler, distributor, broker or agent—is an indirect channel. In an indirect channel, the product passes through one or more intermediaries. That doesn’t mean the producer will do no marketing directly to consumers. Levi’s runs ads on TV that are designed to appeal directly to consumers. The makers of food products run coupon ads. However, the seller must also focus its selling efforts on these intermediaries because the intermediary can help with the selling effort. Not everyone wants to buy Levi’s online.

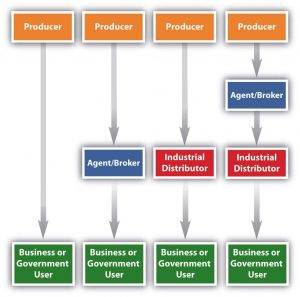

Figure 1.4.2 shows the marketing channels common in business-to-business (B2B) markets. Notice how the channels resemble those in B2C markets, except that the products are sold to businesses and governments instead of consumers like you. The industrial distributors shown in Figure 1.4.2 are firms that supply products that businesses or government departments and agencies use but don’t resell. Grainger Industrial Supply, which sells tens of thousands of products, is one of the world’s largest industrial distributors. Nearly two million businesses and institutions in 150 countries buy products from the company, ranging from padlocks to painkillers.

Disintermediation

You might be tempted to think middlemen or intermediaries are bad. If you can cut them out of the deal—a process marketing professionals call disintermediation—products can be sold more cheaply, can’t they? Large retailers, including Target and Walmart, sometimes bypass middlemen. Instead, they buy their products directly from manufacturers and then store and distribute them to their own retail outlets. Walmart is increasingly doing so and even purchasing produce directly from farmers around the world (Birchall, 2010). However, sometimes cutting out the middleman is desirable, but not always. A wholesaler with buying power and excellent warehousing capabilities might be able to purchase, store, and deliver a product to a seller more cheaply than its producer could, acting alone. Walmart doesn’t need a wholesaler’s buying power, but your local In ‘n Out convenience store does. Likewise, hiring a distributor will cost a producer money. However, if the distributor can help the producer sell greater quantities of a product, it can increase the producer’s profits.

Moreover, when you cut out the middlemen you work with, you have to perform the functions they once did. Maybe it’s storing the product or dealing with hundreds of retailers. More than one producer has ditched its intermediaries and only rehired them later because of the hassles involved.

The trend today is toward disintermediation. The Internet has facilitated a certain amount of disintermediation by making it easier for consumers and businesses to contact one another without going through any middlemen. The Internet has also made it easier for buyers to shop for the lowest prices on products. Today, most people book trips online without going through travel agents. People also shop for homes online rather than using real estate agents. To remain in business, resellers need to find new ways to add value to products.

However, disintermediation via the Internet doesn’t work so well for some products. Insurance is an example. You can buy it online directly from companies, but many people want to buy through an agent they can talk to for advice.

Sometimes, it’s simply impossible to cut out middlemen. Would the Coca-Cola Company want to take the time and trouble to personally sell you an individual can of Coke? No. Coke is no more capable of selling individual Cokes to people than Santa is capable of delivering toys to children around the globe. Even Dell, which initially made its mark by selling computers straight to users, now sells its products through retailers such as Best Buy as well. Dell found that to compete effectively, its products needed to be placed in stores alongside Hewlett-Packard, Acer, and other computer brands (Kraemeer & Dedrick, 2008).

Multiple Channels and Alternate Channels

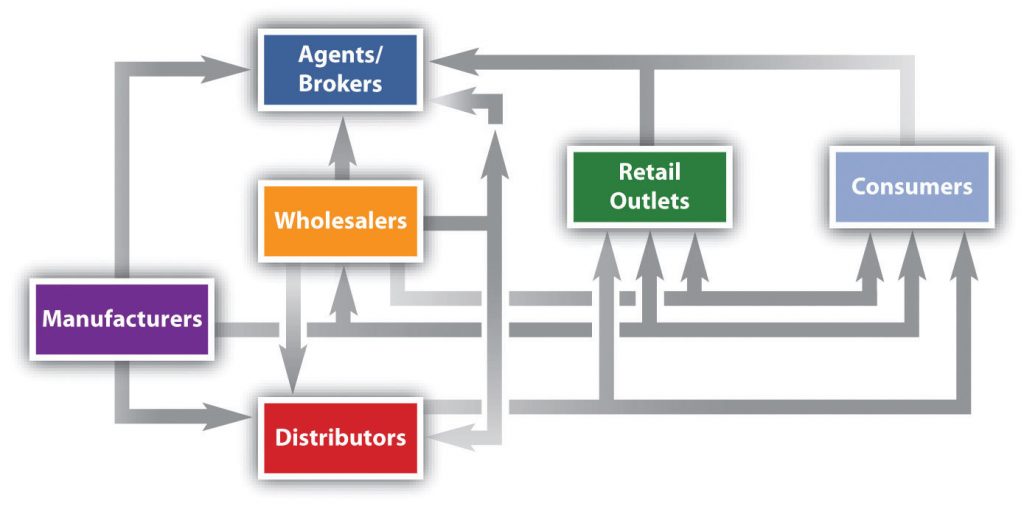

Marketing channels can get a lot more complex than the channels shown in Figure 1.4.1 and Figure 1.4.2 though. Look at the channels in Figure 1.4.3. Notice how, in some situations, a wholesaler will sell to brokers, who then sell to retailers and consumers. In other situations, a wholesaler will sell straight to retailers or straight to consumers. Manufacturers also sell straight to consumers and, as we explained, sell straight to large retailers like Target.

The point is that firms can and do utilize multiple channels. Take Levi’s, for example. You can buy a pair of Levi’s from a retailer such as Kohl’s, or you can buy a pair directly from Levi’s at one of the outlet stores it owns around the country. You can also buy a pair from the Levi’s website.

The key is understanding the different target markets for your product and designing the best channel to meet the needs of customers in each. Is there a group of buyers who would purchase your product if they could shop online from the convenience of their homes? Perhaps there is a group of customers interested in your product, but they do not want to pay full price. The ideal way to reach these people might be through an outlet store with low prices. Each group then needs to be marketed accordingly. Many people regularly interact with companies via numerous channels before making buying decisions.

Segmentation in B2B Markets

Many of the same bases used to segment consumer markets are also used to segment B2B markets. For example, Goya Foods is a U.S. food company that sells different ethnic products to grocery stores, depending on the demographic groups the stores serve—Hispanic, Mexican, or Spanish. Likewise, B2B sellers often divide their customers by geographic areas and tailor their products to them accordingly. Segmenting by behaviour is common as well. B2B sellers frequently divide their customers based on their product usage rates. Customers who order many goods and services from a seller often receive special deals and are served by salespeople who call on them in person. By contrast, smaller customers are more likely to have to rely on a firm’s website, customer service people, and salespeople who call on them by telephone.

Researchers Matthew Harrison, Paul Hague, and Nick Hague have theorized that there are fewer behavioural and needs-based segments in B2B markets than in business-to-consumer (B2C) markets for two reasons: (1) business markets are made up of a few hundred customers, whereas consumer markets can be made up of hundreds of thousands of customers, and (2) businesses aren’t as fickle as consumers. Unlike consumers, they aren’t concerned about their social standing or influenced by their families and peers. Instead, businesses are concerned solely with buying products that will ultimately increase their profits. According to Harrison, Hague, and Hague, the behavioural, or needs-based, segments in B2B markets include the following:

- A price-focused segment is composed of small companies that have low profit margins and regard the good or service being sold as not being strategically important to their operations.

- A quality and brand-focused segment is composed of firms that want the best possible products and are prepared to pay for them.

- A service-focused segment is composed of firms that demand high-quality products and have top-notch delivery and service requirements.

- A partnership-focused segment is composed of firms that seek trust and reliability on the part of their suppliers and see them as strategic partners (Harrison & Hague, 2010).

B2B sellers, like B2C sellers, are exploring new ways to reach their target markets. Trade shows and direct mail campaigns are two traditional ways of reaching B2B markets. However, firms find they can target their B2B customers more cost-effectively via e-mail campaigns, search engine marketing, and “fan pages” on social networking sites.

International Marketing Channels

Consumer and business markets in the United States are well-developed and are slowly growing. However, the growth opportunities abound in other countries. Coca-Cola, in fact, earns most of its income abroad—not in the United States. The company’s latest push is into China, where the per-person consumption of ready-to-drink beverages is only about a third of the global average (Waldmeir, 2009).

The question is how to enter these markets. Via what marketing channels? Some third-world countries lack good intermediary systems. In these countries, firms are on their own in selling and distributing products downstream to users. Other countries have elaborate marketing channels that must be navigated. Consider Japan, for example. Japan has an extensive, complicated system of intermediaries, each of which demands a cut of a company’s profits. Carrefour, a global chain of hypermarkets, tried to expand there but eventually left the country because its marketing channel system was so complicated.

Walmart managed to develop a presence in Japan only after acquiring the Japanese supermarket operator Seiyu (Boyle, 2009). Acquiring part or all of a foreign company is a common strategy for companies. It is referred to as making a direct foreign investment. However, as you learned, some nations don’t allow foreign companies to do business within their borders or buy local companies. The Chinese government blocked Coca-Cola from buying Huiyuan Juice, the country’s largest beverage maker.

Corruption and unstable governments also make it difficult to do business in some countries. The banana company Chiquita found itself in the bad position of having to pay off rebels in Colombia to prevent them from seizing the banana plantations of one of its subsidiaries.

A joint venture is one of the easier ways of utilizing intermediaries to expand abroad. A joint venture is an entity created when two parties agree to share their profits, losses, and control with one another in an economic activity they jointly undertake. The German automaker Volkswagen has struggled to penetrate Asian markets. It recently signed an agreement with Suzuki, the Japanese company, in an effort to challenge Toyota’s dominance in Asia. Will it work? Time will tell. Many joint ventures fail, particularly when they involve companies from different countries. Daimler-Chrysler, the union between the German car company and U.S. automaker Chrysler, is one of many joint ventures that fell by the wayside (Shafer & Reed, 2009). However, in some countries, such as India, it is the only way companies are allowed to do business within their borders.

“Louvre” by Juan Salmoral, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

An even easier way to enter markets is to simply export your products. Microsoft hasn’t done well with its Zune MP3 player in the United States. It subsequently redesigned the product and launched it in other countries (Bradshaw, 2009). Companies can sell their products directly to other firms abroad, or they can hire intermediaries such as brokers and agents who specialize in international exporting to help them find potential buyers for their products.

Recall that many companies, particularly those in the United States, have expanded their operations via franchising. Franchising grants an independent operator the right to use a company’s business model, name, techniques, and trademarks for a fee. McDonald’s is the classic example of a franchise. Unlike Walmart, McDonald’s has had no trouble making headway in Japan. It has done so by selling thousands of franchises there. Japan is McDonald’s second-largest market after the United States. The company also has thousands of franchises in Europe and other countries. There is even a McDonald’s franchise in the Louvre, the prestigious museum in Paris that houses the Mona Lisa. Licensing is similar to franchising. For a fee, a firm can buy the right to use another firm’s manufacturing processes, trade secrets, patents, and trademarks for a certain period.

Key Takeaways

A direct marketing channel consists of just two parties—a producer and a consumer. By contrast, a channel that includes one or more intermediaries (wholesaler, distributor, broker or agent) is an indirect channel. Firms often utilize multiple channels to reach more customers and increase their effectiveness. Some companies find ways to increase their sales by forming strategic channel alliances with one another. Other companies look for ways to cut out the middlemen from the channel, a process known as disintermediation. Direct foreign investment, joint ventures, exporting, franchising, and licensing are some of the channels by which firms attempt to enter foreign markets.

“8.2 Typical Marketing Channels” from Principles of Marketing by [Author removed at the request of original publisher] is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.