1.1 Defining Marketing

Marketing is defined by the American Marketing Association as; the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large (American Marketing Association, n.d.).

Marketing is more than just banner ads, television commercials, and people standing on roadsides dressed up like the Statue of Liberty during tax time. It’s a complex set of activities and strategies that influences where we live, what we wear, how we conduct business, and how we spend our time and money. Marketing activities are conducted in an environment that changes quickly both in terms of customer demand and the methods by which consumers obtain information and make purchases. In the golf industry, loyalty is worth every dollar spent in an effort to achieve; therefore, building relationships is the first step to realizing profits. The following video has some working definitions of marketing.

What Is Marketing?

Video: “What is Marketing? Two Answers To This One Question” [3:44] by Mirasee is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Captions and transcripts are available on YouTube.

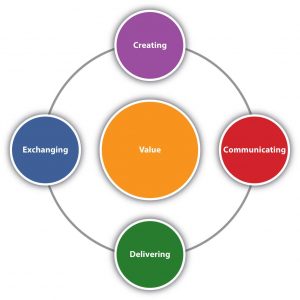

There are four activities, or components, of marketing:

- Creating. The process of collaborating with suppliers and customers to create value offerings.

- Communicating. Broadly, describing those offerings, as well as learning from customers.

- Delivering. Getting those offerings to the consumer in a way that optimizes value.

- Exchanging. Trading value for those offerings.

The traditional way of viewing the components of marketing is via the four Ps:

- Product. Goods and services (creating offerings).

- Promotion. Communication.

- Place. Getting the product to a point at which the customer can purchase it (delivering).

- Price. The monetary amount charged for the product (exchanging).

Introduced in the early 1950s, the four Ps were called the marketing mix, meaning that a marketing plan is a mix of these four components.

If the four Ps are the same as creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging, then you might be wondering why there was a change. The answer is that they are not exactly the same. Product, price, place, and promotion are nouns. As such, these words fail to capture all the activities of marketing. For example, exchanging requires mechanisms for a transaction, which consist of more than simply a price or place. Exchanging requires, among other things, the transfer of ownership. For example, when you buy a car, you sign documents that transfer the car’s title from the seller to you. That’s part of the exchange process.

Even the term product, which seems pretty obvious, is limited. Does the golf membership include services at the golf club (such as a free locker or club storage for a certain period of time)? Or does the product mean only the use of the golf facilities only?

None of the four Ps describes particularly well what marketing people do. However, one of the goals of this book is to focus on exactly what it is that marketing professionals do specifically for the golf industry to maximize customer value and loyalty while cashing in.

Value

Value is at the centre of everything marketing does (Figure 1.1.1). What does value mean? When we use the term value, we mean the benefits buyers receive that meet their needs. In other words, value is what the customer gets by purchasing and consuming a company’s offering.

So, although the company creates the offering, the value is determined by the customer.

Furthermore, as marketers, we aim to create a profitable exchange for consumers. By profitable, we mean the consumer’s personal value equation is positive. The personal value equation is:

Hassle is the time and effort the consumer puts into the shopping process. The equation is a personal one because how each consumer judges the benefits of a product will vary, as will the time and effort he or she puts into shopping. Value, then, varies for each consumer.

One way to think of value is to think of a meal in a restaurant. If you and three friends go to a restaurant and order the same dish, each of you will like it more or less, depending on your tastes. Yet the dish was exactly the same, priced the same, and served exactly the same way. Because your tastes vary, the benefits you receive vary. Therefore, the value varied for each of you. That’s why we call it a personal value equation.

Value varies from customer to customer based on each customer’s needs. The marketing concept, a philosophy underlying all that marketers do, requires that marketers seek to satisfy customer wants and needs. Firms operating with that philosophy are said to be market-oriented. At the same time, market-oriented firms recognize that exchange must be profitable for the company to be successful. A marketing orientation is not an excuse to fail to make a profit.

Firms don’t always embrace the marketing concept and a market orientation. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s, companies were production-orientated. They believed that the best way to compete was by reducing production costs. In other words, companies thought that good products would sell themselves. Perhaps the best example of such a product was Henry Ford’s Model A automobile, the first product of his production line innovation. Ford’s production line made the automobile cheap and affordable for everyone.

From the 1920s until after World War II, companies tended to be selling-orientated, meaning they believed pushing their products by heavily emphasizing advertising and selling was necessary. Consumers during the Great Depression and World War II did not have as much money, so the competition for their available dollars was stiff. The result was this push approach during the selling era. Companies like the Fuller Brush Company and Hoover Vacuum began selling door-to-door, and the vacuum cleaner salesman (who were always men) was created. Just as with production, some companies still operate with a push focus.

In the post–World War II environment, demand for goods increased as the economy soared. Some products, limited in supply during World War II, were now plentiful to the point of surplus. Companies believed that a way to compete was to create products that were different from the competition, so many focused on product innovation. This focus on product innovation is called product orientation. Companies like Procter & Gamble created many products that served the same basic function but with a slight twist or difference in order to appeal to a different consumer, and as a result, products proliferated. However, as consumers had many choices available to them, companies had to find new ways to compete. Which products were best to create? Why create them? The answer was to create what customers wanted, leading to the development of the marketing concept. During this time, the marketing concept was developed, and from about 1950 to 1990, businesses operated in the marketing era.

So, what era would you say we’re in now? Some call it the value era: a time when companies emphasize creating value for customers. Is that really different from the marketing era, in which the emphasis was on fulfilling the marketing concept? Maybe not. Others call today’s business environment the one-to-one era, meaning that the way to compete is to build relationships with customers one at a time and seek to serve each customer’s needs individually.

For example, the longer you are a customer of Amazon, the more detail they gain in your purchasing habits and the better they can target you with offers of new products. With the advent of social media, AI, and the empowerment of consumers through ubiquitous information that includes consumer reviews, there is clearly greater emphasis on meeting customer needs.

Still, others argue that this is the time of service-dominant logic and that we are in the service-dominant logic era. Service-dominant logic is an approach to business that recognizes that consumers want value no matter how it is delivered, whether it’s via a product, a service, or a combination of the two. Although there is merit in this belief, there is also merit to the value approach and the one-to-one approach. As you will see throughout this book, all three are intertwined. Perhaps, then, the name for this era has yet to be devised.

Creating Offerings That Have Value

Marketing creates those goods and services that the company offers at a price to its customers or clients. That entire bundle consists of the tangible good, the intangible service, and the price, which is the company’s offering. When you compare one golf club or set of clubs to another, for example, you can separately evaluate each of these dimensions—the tangible, the intangible, and the price. However, you can’t buy one manufacturer’s golf clubs, another manufacturer’s service, and a third manufacturer’s price when you actually make a choice. Together, the three make up a single firm’s offer.

Marketing people do not create the offering alone. For example, Apple engineers were also involved in the design of the iPad. Apple’s financial personnel had to review the costs of producing the offering and provide input on how it should be priced. Apple’s operations group needed to evaluate the manufacturing requirements the iPad would need. The company’s logistics managers had to evaluate the cost and timing of getting the offering to retailers and consumers. Apple’s dealers also likely provided input regarding the iPad’s service policies and warranty structure. Marketing, however, has the biggest responsibility because it is marketing’s responsibility to ensure that the new product delivers value.

Golf Example

Video: “The Experts’ Take | Episode 5 | The Value Proposition in Golf” by Play Golf Myrtle Beach [10:43] is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Captions and transcripts are available on YouTube.

Communicating Offerings

Communicating is a broad term in marketing that means describing the offering and its value to your potential and current customers, as well as learning from customers what it is they want and like. Understanding market segments and their unique desires is necessary for effective communication.

Sometimes, communicating means educating potential customers about the value of an offering, and sometimes, it means simply making customers aware of where they can find a product. Communicating also means that customers get a chance to tell the company what they think. Today, companies are finding that to be successful, they need to have a more interactive dialogue with their customers. For example, Comcast customer service representatives monitor Twitter. When they observe consumers tweeting problems with Comcast, the customer service reps will post resolutions to their problems. Similarly, JCPenney has created consumer groups that talk among themselves on JCPenney-monitored websites. The company might post questions, send samples, or engage in other activities designed to solicit feedback from customers.

Mobile devices, like iPads and Droid smartphones, make mobile marketing possible, too. For example, if consumers check in at a shopping mall on Foursquare or Facebook, stores in the mall can send coupons and other offers directly to their phones and pad computers.

Companies use many forms of communication, including advertising on the web or television, on billboards or in magazines, through product placements in movies, and through salespeople.

Delivering Offerings

Marketing can’t just promise value; it also has to deliver value. Delivering an offering that has value is much more than simply getting the product into the hands of the user; it is also making sure that the user understands how to get the most out of the product and is taken care of if he or she requires service later.

Value is delivered in part through a company’s supply chain. The supply chain includes a number of organizations and functions that mine, make, assemble, or deliver materials and products from a manufacturer to consumers. The actual group of organizations can vary greatly from industry to industry, including wholesalers, transportation companies, and retailers. Logistics, or the actual transportation and storage of materials and products, is the primary component of supply chain management.

Exchanging Offerings

In addition to creating an offering, communicating its benefits to consumers, and delivering the offering, there is the actual transaction, or exchange, that has to occur. In most instances, we consider the exchange to be cash for products and services. However, if you were to fly to Louisville, Kentucky, for the Kentucky Derby, you could “pay” for your airline tickets using frequent-flier miles. You could also use Hilton Honors points to “pay” for your hotel and cashback points on your Discover card to pay for meals. None of these transactions would actually require cash, but loyalty or long-term residual business is required. Other exchanges, such as information about your preferences gathered through surveys, might not involve cash.

When consumers acquire, consume, and dispose of products and services, exchange occurs, including during the consumption phase. For example, via Apple’s “One-to-One” program, you can pay a yearly fee in exchange for additional periodic product training sessions with an Apple professional. So, each time a training session occurs, another transaction takes place. A transaction also occurs when you are finished with a product. For example, you might sell your old iPhone to a friend, trade in a car, or ask the Salvation Army to pick up your old refrigerator.

Stores like Dick’s Sporting Good’s and Golf Town offer trade-in programs along with most private golf clubs, which allow the customer to recycle old equipment, earn value toward new equipment, and add value to the purchasing cycle for a loyal golfer.

Key Takeaways

The focus of marketing has changed from emphasizing the product, price, place, and promotion mix to one that emphasizes creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging value. Value is a function of the benefits an individual receives and consists of the price the consumer paid and the time and effort the person expended making the purchase.

“1.1 Defining Marketing” from Principles of Marketing by [Author removed at the request of original publisher] is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.