16.3 – Physiology (Function) of the Nervous System

The nervous system is involved in receiving information about the environment around us (sensation) and generating responses to that information (motor responses). The nervous system can be divided into regions that are responsible for sensation (sensory functions) and for the response (motor functions). But there is a third function that needs to be included. Sensory input needs to be integrated with other sensations, as well as with memories, emotional state, or learning (cognition). Some regions of the nervous system are termed integration or association areas. The process of integration combines sensory perceptions and higher cognitive functions such as memories, learning, and emotion to produce a response.

Sensation

The first major function of the nervous system is sensation—receiving information about the environment to gain input about what is happening outside the body (or, sometimes, within the body). The sensory functions of the nervous system register the presence of a change from homeostasis or a particular event in the environment, known as a stimulus. The senses we think of most are the “big five”: taste, smell, touch, sight, and hearing. The stimuli for taste and smell are both chemical substances (molecules, compounds, ions, etc.), touch is physical or mechanical stimuli that interact with the skin, sight is light stimuli, and hearing is the perception of sound, which is a physical stimulus similar to some aspects of touch. There are actually more senses than just those, but that list represents the major senses. Those five are all senses that receive stimuli from the outside world, and of which there is conscious perception. Additional sensory stimuli might be from the internal environment (inside the body), such as the stretch of an organ wall or the concentration of certain ions in the blood.

Response

The nervous system produces a response on the basis of the stimuli perceived by sensory structures. An obvious response would be the movement of muscles, such as withdrawing a hand from a hot stove, but there are broader uses of the term. The nervous system can cause the contraction of all three types of muscle tissue. For example, skeletal muscle contracts to move the skeleton, cardiac muscle is influenced as heart rate increases during exercise, and smooth muscle contracts as the digestive system moves food along the digestive tract. Responses also include the neural control of glands in the body as well, such as the production and secretion of sweat by the eccrine and merocrine sweat glands found in the skin to lower body temperature.

Responses can be divided into those that are voluntary or conscious (contraction of skeletal muscle) and those that are involuntary (contraction of smooth muscles, regulation of cardiac muscle, activation of glands). Voluntary responses are governed by the somatic nervous system and involuntary responses are governed by the autonomic nervous system, which are discussed in the next section.

Integration

Stimuli that are received by sensory structures are communicated to the nervous system where that information is processed. This is called integration. Stimuli are compared with, or integrated with, other stimuli, memories of previous stimuli, or the state of a person at a particular time. This leads to the specific response that will be generated. Seeing a baseball pitched to a batter will not automatically cause the batter to swing. The trajectory of the ball and its speed will need to be considered. Maybe the count is three balls and one strike, and the batter wants to let this pitch go by in the hope of getting a walk to first base. Or maybe the batter’s team is so far ahead, it would be fun to just swing away.

Controlling the Body

The nervous system can be divided into two parts mostly on the basis of a functional difference in responses. The somatic nervous system (SNS) is responsible for conscious perception and voluntary motor responses. Voluntary motor response means the contraction of skeletal muscle, but those contractions are not always voluntary in the sense that you have to want to perform them. Some somatic motor responses are reflexes, and often happen without a conscious decision to perform them. If your friend jumps out from behind a corner and yells “Boo!” you will be startled and you might scream or leap back. You didn’t decide to do that, and you may not have wanted to give your friend a reason to laugh at your expense, but it is a reflex involving skeletal muscle contractions. Other motor responses become automatic (in other words, unconscious) as a person learns motor skills (referred to as “habit learning” or “procedural memory”).

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for involuntary control of the body, usually for the sake of homeostasis (regulation of the internal environment). Sensory input for autonomic functions can be from sensory structures tuned to external or internal environmental stimuli. The motor output extends to smooth and cardiac muscle as well as glandular tissue. The role of the autonomic system is to regulate the organ systems of the body, which usually means to control homeostasis. Sweat glands, for example, are controlled by the autonomic system. When you are hot, sweating helps cool your body down. That is a homeostatic mechanism. But when you are nervous, you might start sweating also. That is not homeostatic, it is the physiological response to an emotional state.

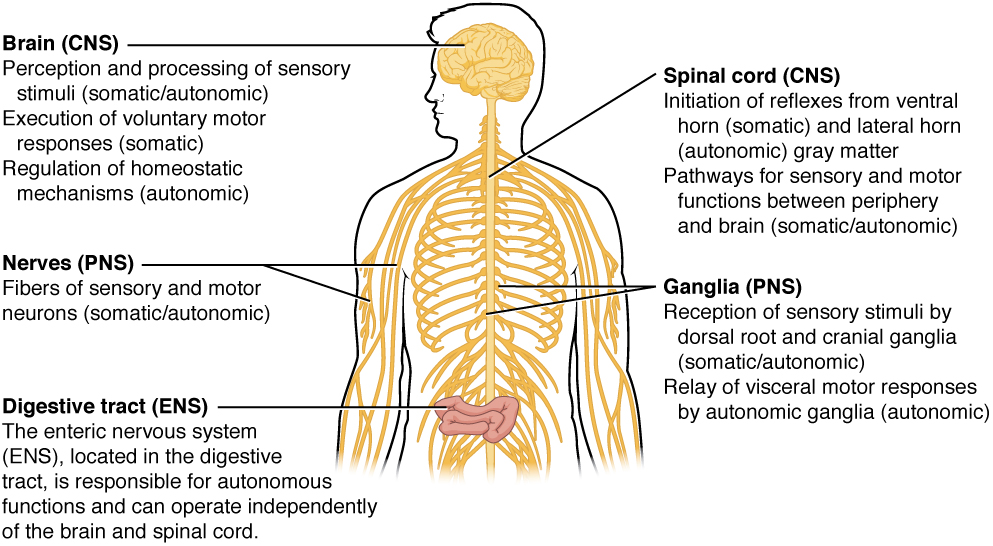

There is another division of the nervous system that describes functional responses. The enteric nervous system (ENS) is responsible for controlling the smooth muscle and glandular tissue in your digestive system. It is a large part of the PNS, and is not dependent on the CNS. It is sometimes valid, however, to consider the enteric system to be a part of the autonomic system because the neural structures that make up the enteric system are a component of the autonomic output that regulates digestion. There are some differences between the two, but for our purposes here there will be a good bit of overlap. See Figure 16.13 for examples of where these divisions of the nervous system can be found.

Functions of the Cerebral Cortex

The cerebrum is the seat of many of the higher mental functions, such as memory and learning, language, and conscious perception, which are the subjects of subtests of the mental status exam. The cerebral cortex is the thin layer of gray matter on the outside of the cerebrum. It is approximately a millimeter thick in most regions and highly folded to fit within the limited space of the cranial vault. These higher functions are distributed across various regions of the cortex, and specific locations can be said to be responsible for particular functions. There is a limited set of regions, for example, that are involved in language function, and they can be subdivided on the basis of the particular part of language function that each governs.

Cognitive Abilities

Assessment of cerebral functions is directed at cognitive abilities. The abilities assessed through the mental status exam can be separated into four groups: orientation and memory, language and speech, sensorium, and judgment and abstract reasoning.

Orientation and Memory

Orientation is the patient’s awareness of his or her immediate circumstances. It is awareness of time, not in terms of the clock, but of the date and what is occurring around the patient. It is awareness of place, such that a patient should know where he or she is and why. It is also awareness of who the patient is—recognizing personal identity and being able to relate that to the examiner. The initial tests of orientation are based on the questions, “Do you know what the date is?” or “Do you know where you are?” or “What is your name?” Further understanding of a patient’s awareness of orientation can come from questions that address remote memory, such as “Who is the President of the United States?”, or asking what happened on a specific date.

Memory is largely a function of the temporal lobe, along with structures beneath the cerebral cortex such as the hippocampus and the amygdala. The storage of memory requires these structures of the medial temporal lobe. A famous case of a man who had both medial temporal lobes removed to treat intractable epilepsy provided insight into the relationship between the structures of the brain and the function of memory.

The prefrontal cortex can also be tested for the ability to organize information. In one subtest of the mental status exam called set generation, the patient is asked to generate a list of words that all start with the same letter, but not to include proper nouns or names. The expectation is that a person can generate such a list of at least 10 words within 1 minute. Many people can likely do this much more quickly, but the standard separates the accepted normal from those with compromised prefrontal cortices.

Read the New York Times Magazine article Forgetting Everything [New Tab] to learn about a young man who texts his fiancée in a panic as he finds that he is having trouble remembering things. At the hospital, a neurologist administers the mental status exam, which is mostly normal except for the three-word recall test. The young man could not recall them even 30 seconds after hearing them and repeating them back to the doctor. An undiscovered mass in the mediastinum region was found to be Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a type of cancer that affects the immune system and likely caused antibodies to attack the nervous system. The patient eventually regained his ability to remember, though the events in the hospital were always elusive. Considering that the effects on memory were temporary, but resulted in the loss of the specific events of the hospital stay, what regions of the brain were likely to have been affected by the antibodies and what type of memory does that represent?

Language and Speech

Language is, arguably, a very human aspect of neurological function. There are certainly strides being made in understanding communication in other species, but much of what makes the human experience seemingly unique is its basis in language. Any understanding of our species is necessarily reflective, as suggested by the question “What am I?” and the fundamental answer to this question is suggested by the famous quote by René Descartes: “Cogito Ergo Sum” (translated from Latin as “I think, therefore I am”). Formulating an understanding of yourself is largely describing who you are to yourself. It is a confusing topic to delve into, but language is certainly at the core of what it means to be self-aware.

The neurological exam has two specific subtests that address language. One measures the ability of the patient to understand language by asking them to follow a set of instructions to perform an action, such as “touch your right finger to your left elbow and then to your right knee.” Another subtest assesses the fluency and coherency of language by having the patient generate descriptions of objects or scenes depicted in drawings, and by reciting sentences or explaining a written passage.

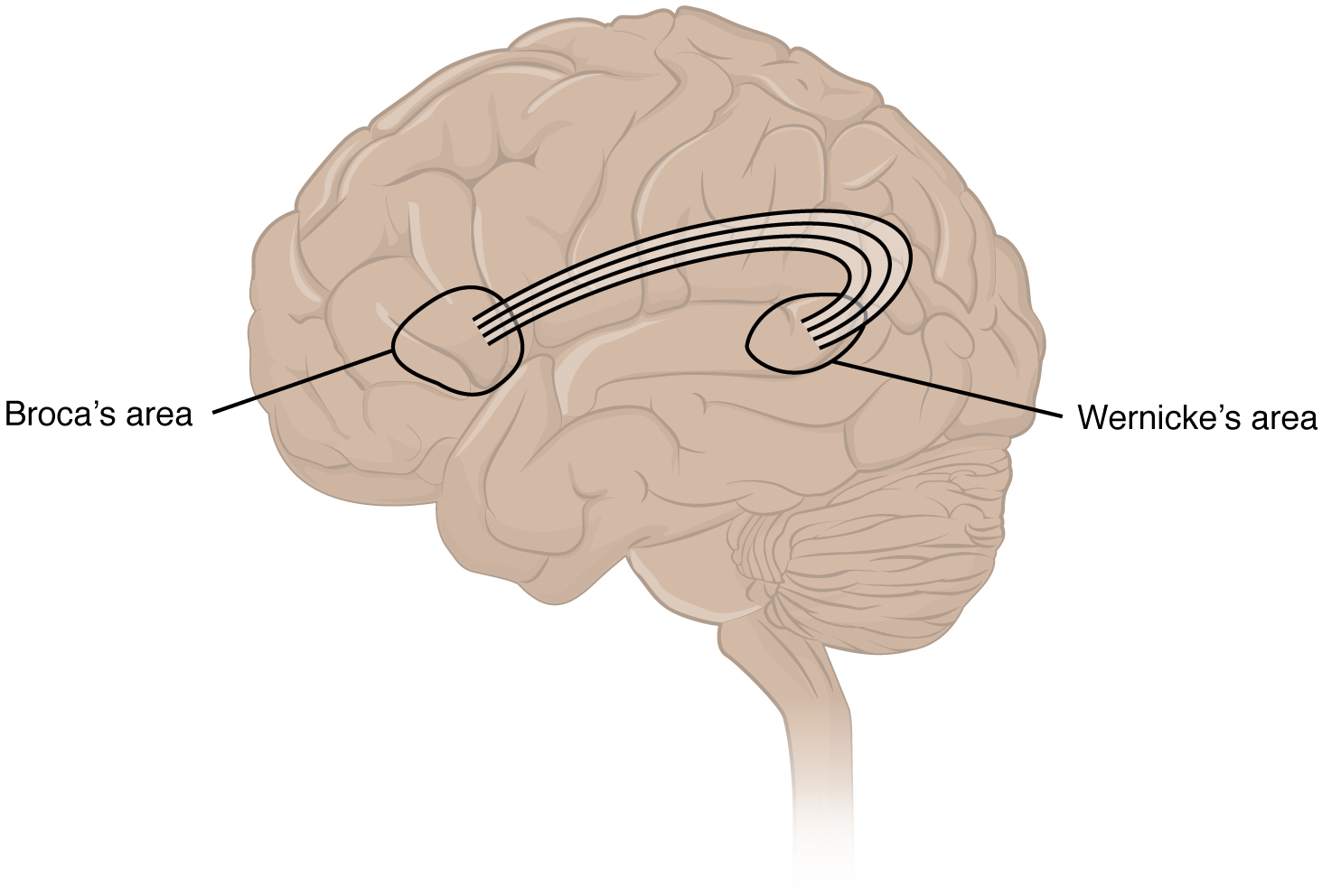

An important example of multimodal integrative areas is associated with language function (see Figure 16.14). Adjacent to the auditory association cortex, at the end of the lateral sulcus just anterior to the visual cortex, is Wernicke’s area. In the lateral aspect of the frontal lobe, just anterior to the region of the motor cortex associated with the head and neck, is Broca’s area. Both regions were originally described on the basis of losses of speech and language, which is called aphasia. The aphasia associated with Broca’s area is known as an expressive aphasia, which means that speech production is compromised. This type of aphasia is often described as non-fluency because the ability to say some words leads to broken or halting speech. Grammar can also appear to be lost. The aphasia associated with Wernicke’s area is known as a receptive aphasia, which is not a loss of speech production, but a loss of understanding of content. Patients, after recovering from acute forms of this aphasia, report not being able to understand what is said to them or what they are saying themselves, but they often cannot keep from talking.

The two regions are connected by white matter tracts that run between the posterior temporal lobe and the lateral aspect of the frontal lobe. Conduction aphasia associated with damage to this connection refers to the problem of connecting the understanding of language to the production of speech. This is a very rare condition, but is likely to present as an inability to faithfully repeat spoken language.

Sensorium

Those parts of the brain involved in the reception and interpretation of sensory stimuli are referred to collectively as the sensorium. The cerebral cortex has several regions that are necessary for sensory perception. Several of the subtests can reveal activity associated with these sensory modalities, such as being able to hear a question or see a picture. Two subtests assess specific functions of these cortical areas.

The first is praxis, a practical exercise in which the patient performs a task completely on the basis of verbal description without any demonstration from the examiner. The second subtest for sensory perception is gnosis, which involves two tasks. The first task, known as stereognosis, involves the naming of objects strictly on the basis of the somatosensory information that comes from manipulating them. The patient keeps their eyes closed and is given a common object, such as a coin, that they have to identify. The patient should be able to indicate the particular type of coin, such as a dime versus a penny, or a nickel versus a quarter, on the basis of the sensory cues involved. For example, the size, thickness, or weight of the coin may be an indication, or to differentiate the pairs of coins suggested here, the smooth or corrugated edge of the coin will correspond to the particular denomination. The second task, graphesthesia, is to recognize numbers or letters written on the palm of the hand with a dull pointer, such as a pen cap.

Judgment and Abstract Reasoning

Planning and producing responses requires an ability to make sense of the world around us. Making judgments and reasoning in the abstract are necessary to produce movements as part of larger responses. For example, when your alarm goes off, do you hit the snooze button or jump out of bed? Is 10 extra minutes in bed worth the extra rush to get ready for your day? Will hitting the snooze button multiple times lead to feeling more rested or result in a panic as you run late? How you mentally process these questions can affect your whole day.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for the functions responsible for planning and making decisions. In the mental status exam, the subtest that assesses judgment and reasoning is directed at three aspects of frontal lobe function. First, the examiner asks questions about problem solving, such as “if you see a house on fire, what would you do?” The patient is also asked to interpret common proverbs, such as “don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.” Additionally, pairs of words are compared for similarities, such as apple and orange, or lamp and cabinet.

Everyday Connections

Left Brain, Right Brain

Popular media often refer to right-brained and left-brained people, as if the brain were two independent halves that work differently for different people. This is a popular misinterpretation of an important neurological phenomenon. As an extreme measure to deal with a debilitating condition, the corpus callosum may be sectioned to overcome intractable epilepsy. When the connections between the two cerebral hemispheres are cut, interesting effects can be observed.

The reason for this is that the language functions of the cerebral cortex are localized to the left hemisphere in 95 percent of the population. Additionally, the left hemisphere is connected to the right side of the body through the corticospinal tract and the ascending tracts of the spinal cord. Motor commands from the precentral gyrus control the opposite side of the body, whereas sensory information processed by the postcentral gyrus is received from the opposite side of the body. For a verbal command to initiate movement of the right arm and hand, the left side of the brain needs to be connected by the corpus callosum. Language is processed in the left side of the brain and directly influences the left brain and right arm motor functions, but is sent to influence the right brain and left arm motor functions through the corpus callosum. Likewise, the left-handed sensory perception of what is in the left pocket travels across the corpus callosum from the right brain, so no verbal report on those contents would be possible if the hand happened to be in the pocket.

People who have had their corpus callosum cut can perform two independent tasks at the same time because the lines of communication between the right and left sides of his brain have been removed. Whereas a person with an intact corpus callosum cannot overcome the dominance of one hemisphere over the other, this patient can. If the left cerebral hemisphere is dominant in the majority of people, why would right-handedness be most common?

Common Nervous System Abbreviations

Common Nervous System Abbreviations

- AD (Alzheimer’s disease)

- ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

- ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)

- CNS (central nervous system)

- CP (cerebral palsy)

- CSF (cerebrospinal fluid)

- CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy)

- CVA (cerebrovascular accident)

- EEG (electroencephalogram)

- EP studies (evoked potential studies)

- LP (lumbar puncture)

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

- MS (multiple sclerosis)

- OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder)

- PD (Parkison’s disease)

- PET (positron emission tomography)

- PNS (peripheral nervous system)

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

- SAH (subarachnoid hemorrhage)

- TIA (transient ischemic attack)

Activity Source: Nervous System Abbreviations by Kim Carter, from Building a Medical Terminology Foundation by Kimberlee Carter and Marie Rutherford, licensed under CC BY 4.0. /Text version added.

Image Descriptions

Figure 16.13 image description: A silhouette of a human with only the brain, spinal cord, PNS ganglia, nerves and a section of the digestive tract visible. The brain, which is part of the CNS, is the area of perception and processing of sensory stimuli (somatic/autonomic), the execution of voluntary motor responses (somatic), and the regulation of homeostatic mechanisms (autonomic). The spinal cord, which is part of the CNS, is the area where reflexes are initiated. The gray matter of the ventral horn initiates somatic reflexes while the gray matter of the lateral horn initiates autonomic reflexes. The spinal cord is also the somatic and autonomic pathway for sensory and motor functions between the PNS and the brain. The nerves, which are part of the PNS, are the fibers of sensory and motor neurons, which can be either somatic or autonomic. The ganglia, which are part of the PNS, are the areas for the reception of somatic and autonomic sensory stimuli. These are received by the dorsal root ganglia and cranial ganglia. The autonomic ganglia are also the relay for visceral motor responses. The digestive tract is part of the enteric nervous system, the ENS, which is located in the digestive tract and is responsible for autonomous function. The ENS can operate independent of the brain and spinal cord. [Return to Figure 16.13].

Attribution

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Nervous System” in Building a Medical Terminology Foundation by Kimberlee Carter and Marie Rutherford, licensed under CC BY 4.0. / A derivative of Betts et al., which can be accessed for free from Anatomy and Physiology (OpenStax). Adaptations: dividing Nervous System chapter content into sub-chapters.