12.2 – Anatomy (Structures) of the Digestive System

The Mouth

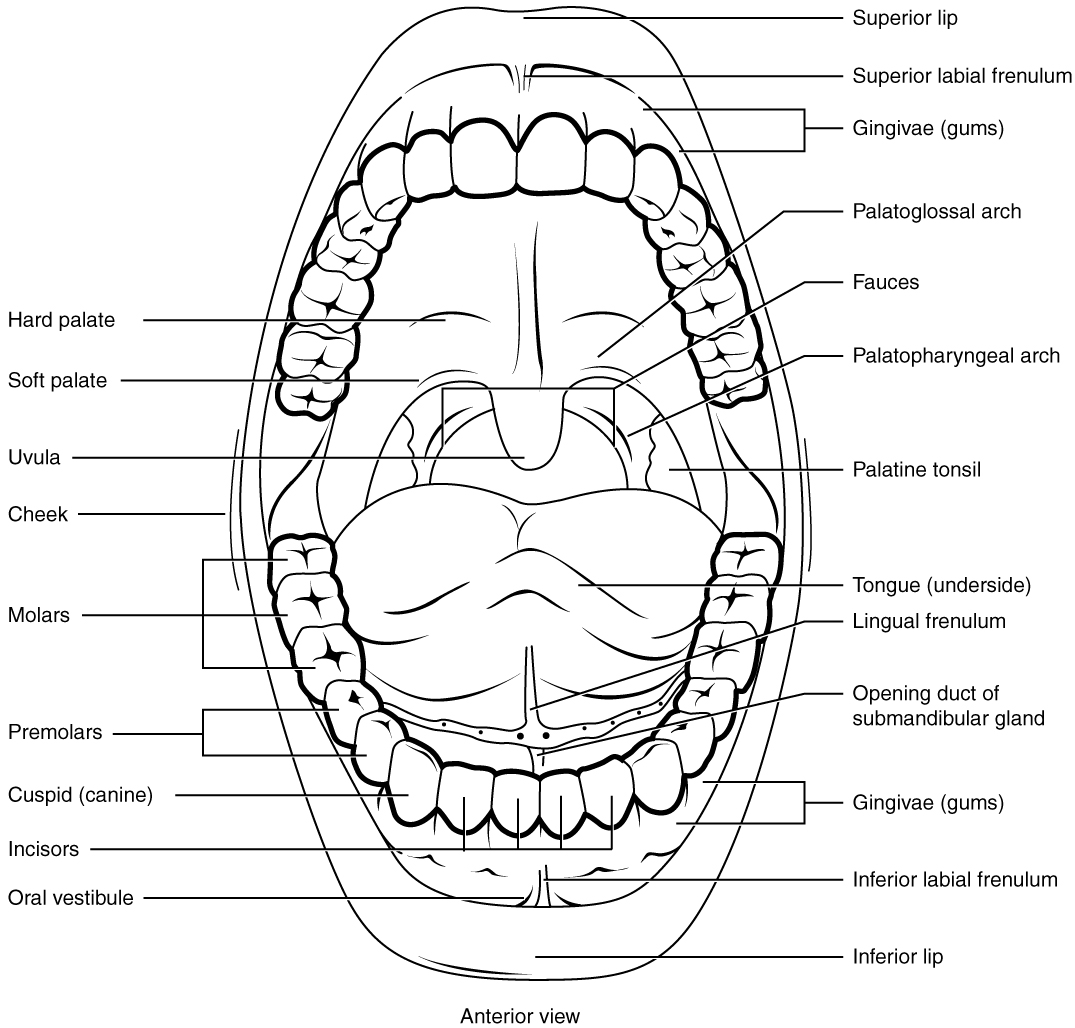

The cheeks, tongue, and palate frame the mouth, which is also called the oral cavity (or buccal cavity). The structures of the mouth are illustrated in Figure 12.2.

At the entrance to the mouth are the lips, or labia (singular = labium). Their outer covering is skin, which transitions to a mucous membrane in the mouth proper. Lips are very vascular with a thin layer of keratin, hence the reason they are red.

The pocket-like part of the mouth that is framed on the inside by the gums and teeth and on the outside by the cheeks and lips is called the oral vestibule. Moving farther into the mouth, the opening between the oral cavity and throat (oropharynx) is called the fauces (like the kitchen “faucet”). The main open area of the mouth, or oral cavity proper, runs from the gums and teeth to the fauces.

When you are chewing, you do not find it difficult to breathe simultaneously. The next time you have food in your mouth, notice how the arched shape of the roof of your mouth allows you to handle both digestion and respiration at the same time. This arch is called the palate. The anterior region of the palate serves as a wall (or septum) between the oral and nasal cavities as well as a rigid shelf against which the tongue can push food. It is created by the maxillary and palatine bones of the skull and, given its bony structure, is known as the hard palate. If you run your tongue along the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice that the hard palate ends in the posterior oral cavity, and the tissue becomes fleshier. This part of the palate, known as the soft palate, is composed mainly of skeletal muscle. You can therefore manipulate, subconsciously, the soft palate—for instance, to yawn, swallow, or sing (see Figure 12.2).

Did You Know 1?

A fleshy bead of tissue called the uvula drops down from the center of the posterior edge of the soft palate. Although some have suggested that the uvula is a vestigial organ, it serves an important purpose. When you swallow, the soft palate and uvula move upward, helping to keep foods and liquid from entering the nasal cavity. Unfortunately, it can also contribute to the sound produced by snoring. Two muscular folds extend downward from the soft palate, on either side of the uvula. Toward the front, the palatoglossal arch lies next to the base of the tongue; behind it, the palatopharyngeal arch forms the superior and lateral margins of the fauces. Between these two arches are the palatine tonsils, clusters of lymphoid tissue that protect the pharynx. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.

Tongue

Perhaps you have heard it said that the tongue is the strongest muscle in the body. Those who stake this claim cite its strength proportionate to its size. Although it is difficult to quantify the relative strength of different muscles, it remains indisputable that the tongue is a workhorse, facilitating ingestion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion (lingual lipase), sensation (of taste, texture, and temperature of food), swallowing, and vocalization.

The tongue is attached to the mandible, the styloid processes of the temporal bones, and the hyoid bone. The hyoid is unique in that it only distantly/indirectly articulates with other bones. The tongue is positioned over the floor of the oral cavity. A medial septum extends the entire length of the tongue, dividing it into symmetrical halves.

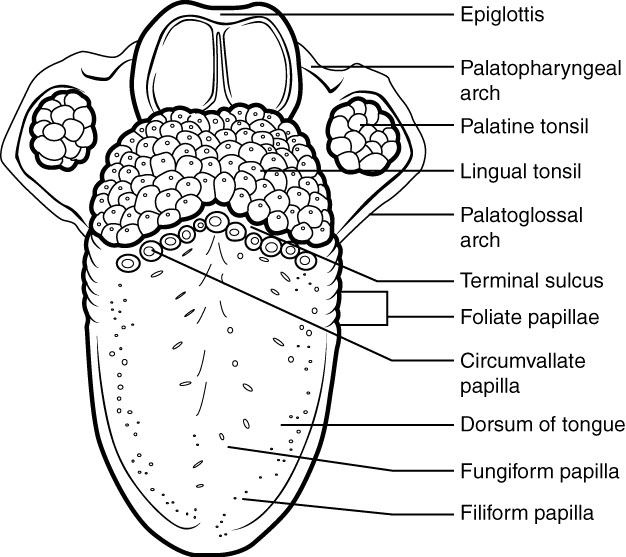

The top and sides of the tongue are studded with papillae, extensions of lamina propria of the mucosa, which are covered in stratified squamous epithelium (see Figure 12.3).

Salivary Glands

Many small salivary glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue. These minor exocrine glands are constantly secreting saliva, either directly into the oral cavity or indirectly through ducts, even while you sleep. In fact, an average of 1 to 1.5 liters of saliva is secreted each day. Usually, just enough saliva is present to moisten the mouth and teeth. Secretion increases when you eat, because saliva is essential to moisten food and initiate the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates. Small amounts of saliva are also secreted by the labial glands in the lips. In addition, the buccal glands in the cheeks, palatal glands in the palate, and lingual glands in the tongue help ensure that all areas of the mouth are supplied with adequate saliva.

Concept Check 1

- Describe how the anatomy of the mouth permits breathing and chewing at the same time

- Explain the role saliva performs in the digestive system

Pharynx

The pharynx (throat) is involved in both digestion and respiration. It receives food and air from the mouth, and air from the nasal cavities. When food enters the pharynx, involuntary muscle contractions close off the air passageways. A short tube of skeletal muscle lined with a mucous membrane, the pharynx runs from the posterior oral and nasal cavities to the opening of the esophagus and larynx. It has three subdivisions. The most superior, the nasopharynx, is involved only in breathing and speech. The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both breathing and digestion. The oropharynx begins inferior to the nasopharynx and is continuous below with the laryngopharynx. The inferior border of the laryngopharynx connects to the esophagus, whereas the anterior portion connects to the larynx, allowing air to flow into the bronchial tree.

Esophagus

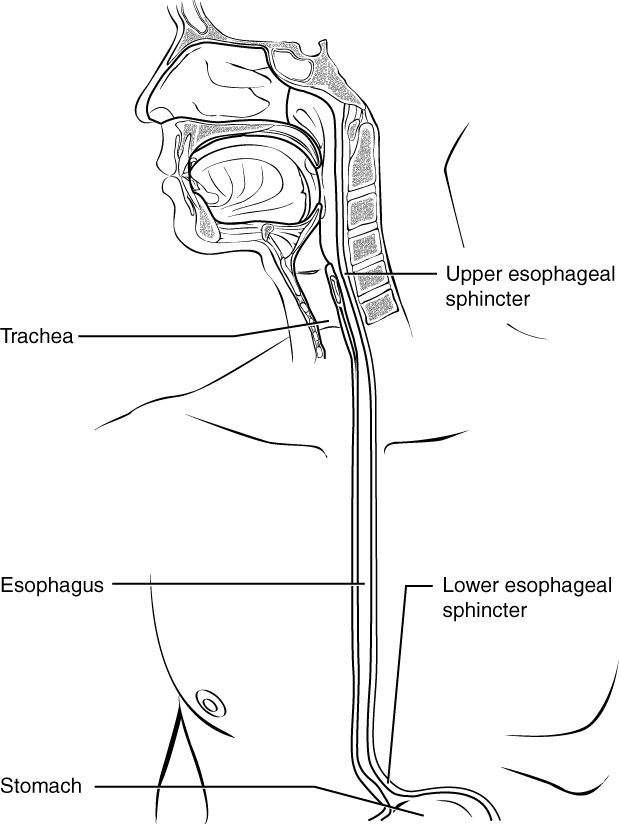

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It is approximately 25.4 cm (10 in) in length, located posterior to the trachea, and remains in a collapsed form when not engaged in swallowing. As you can see in Figure 12.4, the esophagus runs a mainly straight route through the mediastinum of the thorax. To enter the abdomen, the esophagus penetrates the diaphragm through an opening called the esophageal hiatus.

Passage of Food Through the Esophagus

The upper esophageal sphincter, which is continuous with the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, controls the movement of food from the pharynx into the esophagus. The upper two-thirds of the esophagus consists of both smooth and skeletal muscle fibers, with the latter fading out in the bottom third of the esophagus. Rhythmic waves of peristalsis, which begin in the upper esophagus, propel the bolus of food toward the stomach. Meanwhile, secretions from the esophageal mucosa lubricate the esophagus and food. Food passes from the esophagus into the stomach at the lower esophageal sphincter (also called the gastroesophageal or cardiac sphincter). Recall that sphincters are muscles that surround tubes and serve as valves, closing the tube when the sphincters contract and opening it when they relax.

Stomach

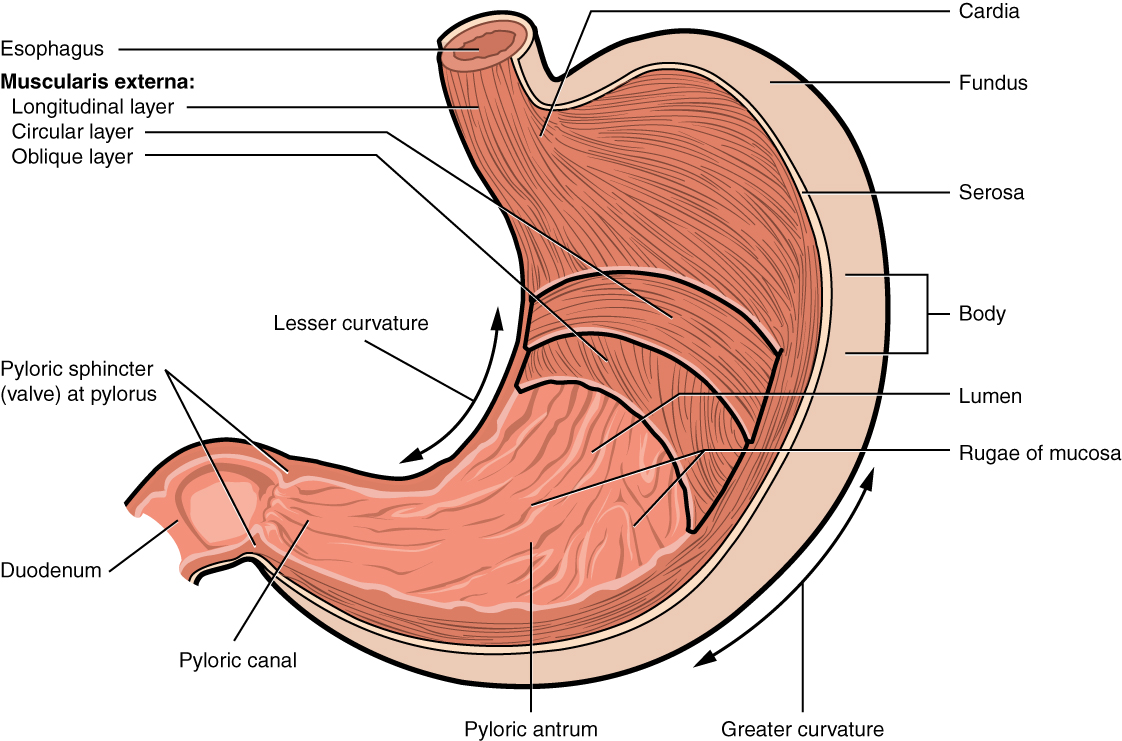

There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus (see Figure 12.5). The cardia (or cardiac region) is the point where the esophagus connects to the stomach and through which food passes into the stomach. Located inferior to the diaphragm, above and to the left of the cardia is the dome-shaped fundus. Below the fundus is the body, the main part of the stomach. The funnel-shaped pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum. The wider end of the funnel, the pyloric antrum, connects to the body of the stomach. The narrower end is called the pyloric canal, which connects to the duodenum. The smooth muscle pyloric sphincter is located at this latter point of connection and controls stomach emptying. In the absence of food, the stomach deflates inward, and its mucosa and submucosa fall into a large fold called a ruga.

The convex lateral surface of the stomach is called the greater curvature; the concave medial border is the lesser curvature. The stomach is held in place by the lesser omentum, which extends from the liver to the lesser curvature, and the greater omentum, which runs from the greater curvature to the posterior abdominal wall. Partially digested food mixed with digestive juices of the stomach becomes known as chyme.

Small Intestines

Chyme released from the stomach enters the small intestine, which is the primary digestive organ in the body. Not only is this where most digestion occurs, it is also where practically all absorption occurs. The longest part of the alimentary canal, the small intestine is about 3.05 meters (10 feet) long in a living person (but about twice as long in a cadaver due to the loss of muscle tone). Since this makes it about five times longer than the large intestine, you might wonder why it is called “small.” In fact, its name derives from its relatively smaller diameter of only about 2.54 cm (1 in), compared with 7.62 cm (3 in) for the large intestine. As we’ll see shortly, in addition to its length, the folds and projections of the lining of the small intestine work to give it an enormous surface area, which is approximately 200 m2, more than 100 times the surface area of your skin. This large surface area is necessary for complex processes of digestion and absorption that occur within it.

Did You Know 2?

Your body absorbs 90 per cent of our nutrients through the small intestine, into your blood.

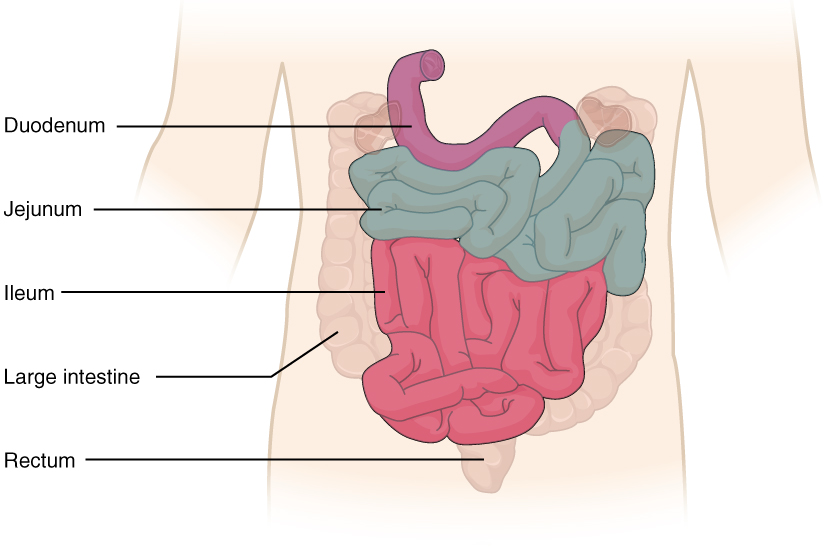

The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three regions. From proximal (at the stomach) to distal, these are the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum (see Figure 12.6).

Large Intestines

The large intestine is the terminal part of the alimentary canal. The primary function of this organ is to finish the absorption of nutrients and water, synthesize certain vitamins, form feces, and eliminate feces from the body.

The large intestine runs from the appendix to the anus. It frames the small intestine on three sides. Despite being about one-half as long as the small intestine, it is called large because it is more than twice the diameter of the small intestine, about 3 inches.

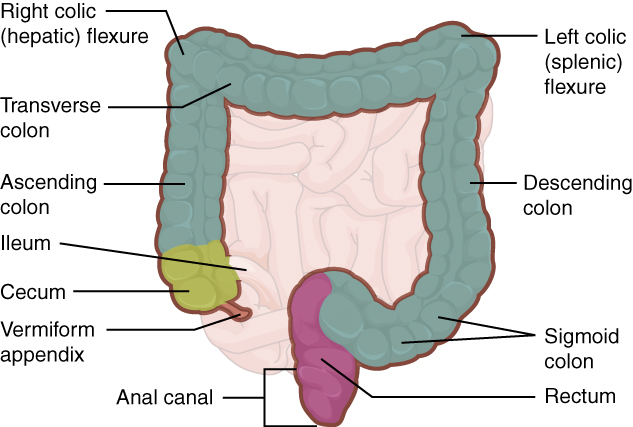

The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anus. The ileocecal valve, located at the opening between the ileum and the large intestine, controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.

Cecum

The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a sac-like structure that is suspended inferior to the ileocecal valve. It is about 6 cm (2.4 in) long, receives the contents of the ileum, and continues the absorption of water and salts. The appendix (or vermiform appendix) is a winding tube that attaches to the cecum. Although the 7.6-cm (3-in) long appendix contains lymphoid tissue, suggesting an immunologic function, this organ is generally considered vestigial. However, at least one recent report assumes a survival advantage conferred by the appendix: in diarrheal illness, the appendix may serve as a bacterial reservoir to repopulate the enteric bacteria for those surviving the initial phases of the illness. Moreover, its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria. The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the mesentery of the ileum.

Colon

The cecum blends seamlessly with the colon. Upon entering the colon, the food residue first travels up the ascending colon on the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to form the right colic flexure (hepatic flexure) and becomes the transverse colon. The region defined as hindgut begins with the last third of the transverse colon and continues on. Food residue passing through the transverse colon travels across to the left side of the abdomen, where the colon angles sharply immediately inferior to the spleen, at the left colic flexure (splenic flexure). From there, food residue passes through the descending colon, which runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall. After entering the pelvis inferiorly, it becomes the s-shaped sigmoid colon, which extends medially to the midline (see Figure 12.7). The ascending and descending colon and the rectum (discussed next) are located in the retroperitoneum. The transverse and sigmoid colon are tethered to the posterior abdominal wall by the mesocolon.

Accessory Organs of Digestion

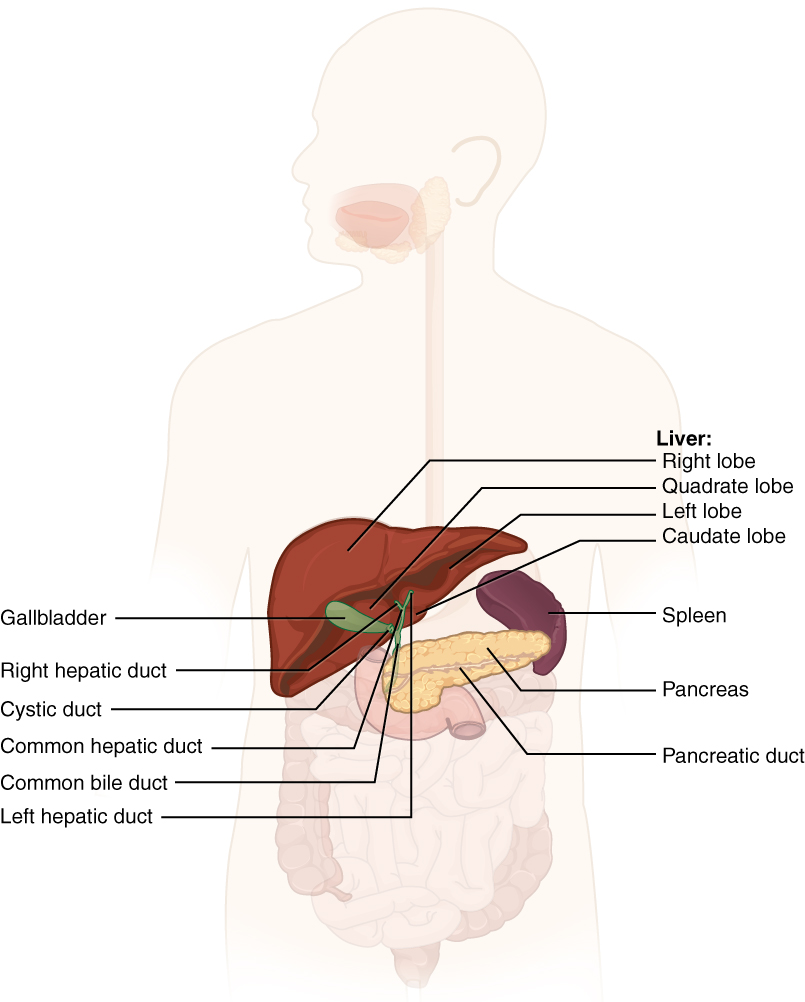

Chemical digestion in the small intestine relies on the activities of three accessory digestive organs: the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder (see Figure 12.8). The digestive role of the liver is to produce bile and export it to the duodenum. The gallbladder primarily stores, concentrates, and releases bile. The pancreas produces pancreatic juice, which contains digestive enzymes and bicarbonate ions, and delivers it to the duodenum.

Concept Check 2

On the Figure 6 diagram, locate the following anatomical organs and consider how these organs support the digestive process:

- Liver

- Pancreas

- Gallbladder

Liver

The liver is the largest gland in the body, weighing about three pounds in an adult. It is also one of the most important organs. In addition to being an accessory digestive organ, it plays a number of roles in metabolism and regulation. The liver lies inferior to the diaphragm in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity and receives protection from the surrounding ribs.

The liver is divided into two primary lobes: a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe. In the right lobe, some anatomists also identify an inferior quadrate lobe and a posterior caudate lobe, which are defined by internal features. The liver is connected to the abdominal wall and diaphragm by five peritoneal folds referred to as ligaments.

The porta hepatis (“gate to the liver”) is where the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein enter the liver. These two vessels, along with the common hepatic duct, run behind the lateral border of the lesser omentum on the way to their destinations. The hepatic portal vein delivers partially deoxygenated blood containing nutrients absorbed from the small intestine and actually supplies more oxygen to the liver than do the much smaller hepatic arteries. In addition to nutrients, drugs and toxins are also absorbed. After processing the bloodborne nutrients and toxins, the liver releases nutrients needed by other cells back into the blood, which drains into the central vein and then through the hepatic vein to the inferior vena cava. With this hepatic portal circulation, all blood from the alimentary canal passes through the liver. This largely explains why the liver is the most common site for the metastasis of cancers that originate in the alimentary canal.

Bile produced by the liver is a mixture secreted by the liver to accomplish the emulsification of lipids in the small intestine.

Bilirubin, the main bile pigment, is a waste product produced when the spleen removes old or damaged red blood cells from circulation. These breakdown products, including proteins, iron, and toxic bilirubin, are transported to the liver via the splenic vein of the hepatic portal system. In the liver, proteins and iron are recycled, whereas bilirubin is excreted in the bile. It accounts for the green color of bile. Bilirubin is eventually transformed by intestinal bacteria into stercobilin, a brown pigment that gives your stool its characteristic color! In some disease states, bile does not enter the intestine, resulting in white (‘acholic’) stool with a high fat content, since virtually no fats are broken down or absorbed.

Between meals, bile is produced but conserved. The valve-like hepatopancreatic ampulla closes, allowing bile to divert to the gallbladder, where it is concentrated and stored until the next meal.

Pancreas

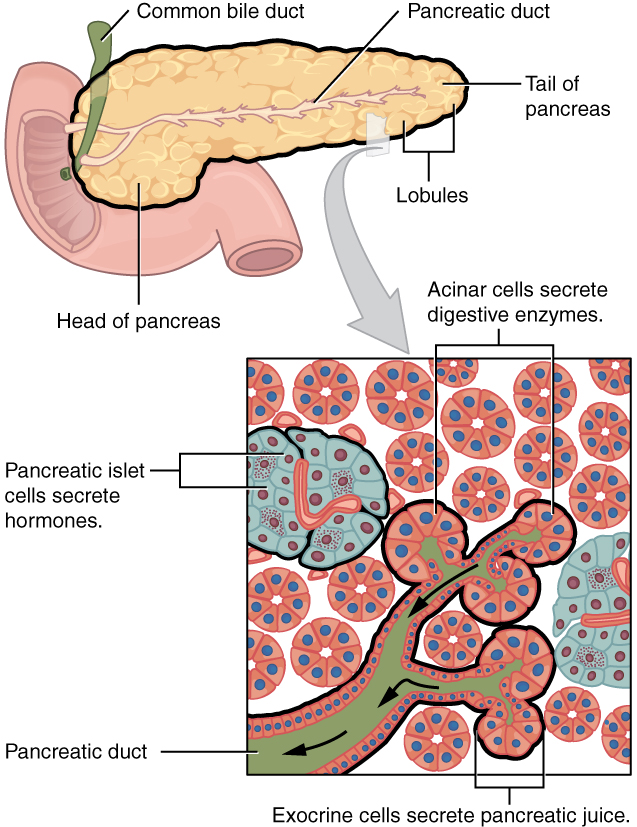

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas lies transversely in the retroperitoneum behind the stomach. Its head is nestled into the “c-shaped” curvature of the duodenum with the body extending to the left about 15.2 cm (6 in) and ending as a tapering tail in the hilum of the spleen. It is a curious mix of exocrine (secreting digestive enzymes) and endocrine (releasing hormones into the blood) functions (Figure 12.9).

The exocrine part of the pancreas arises as little grape-like cell clusters, each called an acinus (plural = acini), located at the terminal ends of pancreatic ducts. These acinar cells secrete enzyme-rich pancreatic juice into tiny merging ducts that form two dominant ducts. The larger duct fuses with the common bile duct (carrying bile from the liver and gallbladder) just before entering the duodenum via a common opening (the hepatopancreatic ampulla). The smooth muscle sphincter of the hepatopancreatic ampulla controls the release of pancreatic juice and bile into the small intestine. The second and smaller pancreatic duct, the accessory duct (duct of Santorini), runs from the pancreas directly into the duodenum, approximately 1 inch above the hepatopancreatic ampulla. When present, it is a persistent remnant of pancreatic development.

Scattered through the sea of exocrine acini are small islands of endocrine cells, the islets of Langerhans. These vital cells produce the hormones pancreatic polypeptide, insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin.

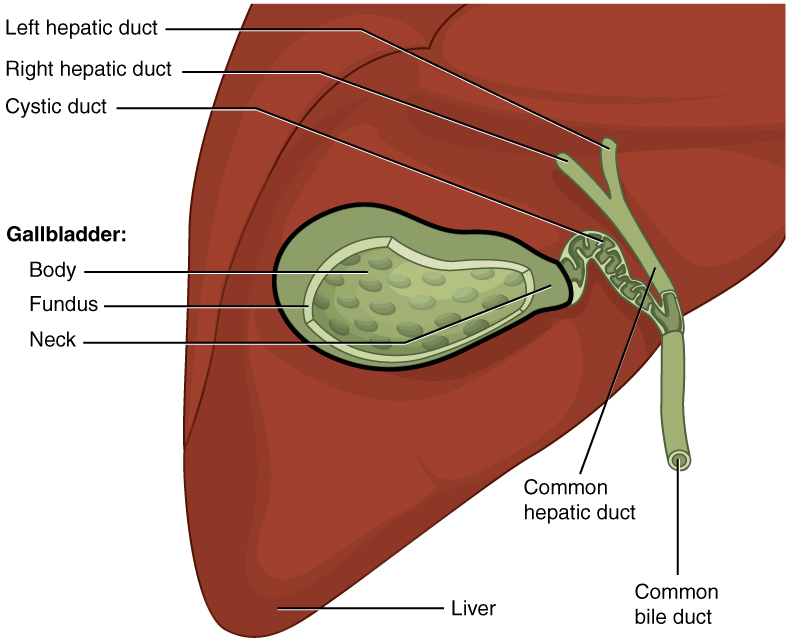

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is 8–10 cm (~3–4 in) long and is nested in a shallow area on the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver. This muscular sac stores, concentrates, and, when stimulated, propels the bile into the duodenum via the common bile duct. It is divided into three regions. The fundus is the widest portion and tapers medially into the body, which in turn narrows to become the neck. The neck angles slightly superiorly as it approaches the hepatic duct. The cystic duct is 1–2 cm (less than 1 in) long and turns inferiorly as it bridges the neck and hepatic duct.

The simple columnar epithelium of the gallbladder mucosa is organized in rugae, similar to those of the stomach. There is no submucosa in the gallbladder wall. The wall’s middle, muscular coat is made of smooth muscle fibers. When these fibers contract, the gallbladder’s contents are ejected through the cystic duct and into the bile duct (Figure 12.10). Visceral peritoneum reflected from the liver capsule holds the gallbladder against the liver and forms the outer coat of the gallbladder. The gallbladder’s mucosa absorbs water and ions from bile, concentrating it by up to 10-fold (Betts et al., 2013).

Concept Check 3

- Locate the cystic duct on the diagram shown.

- Consider what complications could arise if this duct was blocked or obstructed.

Watch the following video to see the structure of the liver and how this structure supports the functions of the liver, including the processing of nutrients, toxins, and wastes. At rest, about 1500 mL of blood per minute flow through the liver. What percentage of this blood flow comes from the hepatic portal system? (Betts et al., 2013).

Watch How the Body Works: The Architecture of the Liver (1 min) on YouTube

Media 12.2: Izzo, D. [Daniel Izzo]. (2007, August 3). How the body works : The architecture of the liver [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Gn-ibhGE7PI

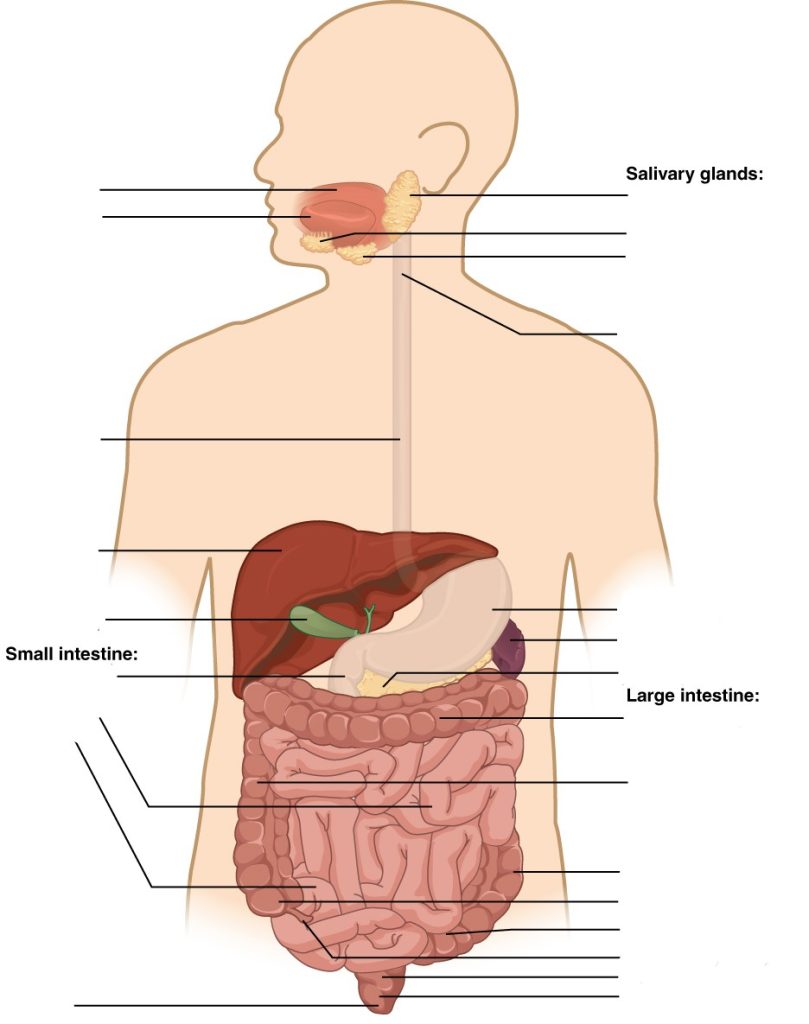

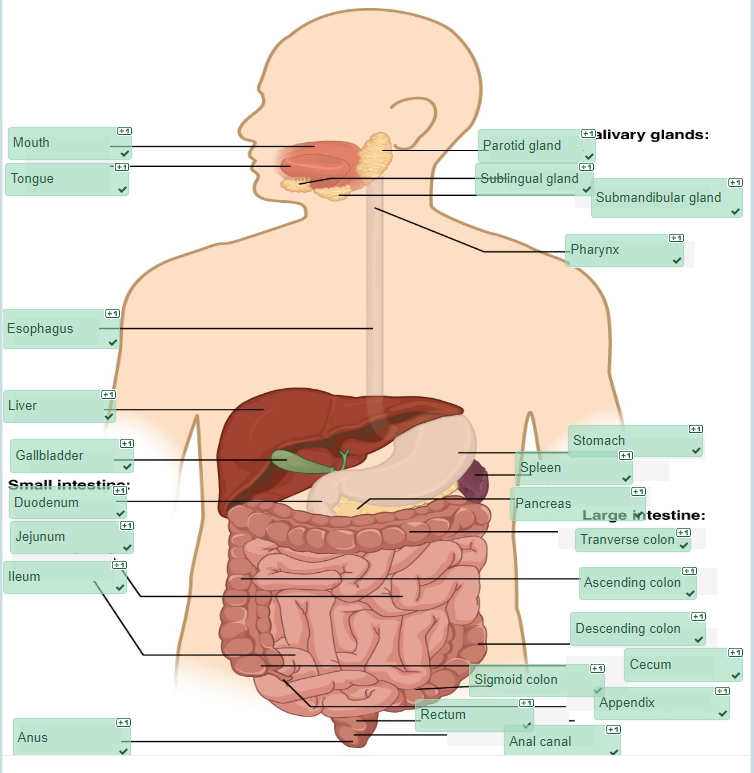

Check Your Knowledge of the Digestive System

Anatomy Labeling Activity

Digestive System Anatomy (Text Version)

Label the diagram with correct words listed below:

- Gallbladder

- Mouth

- Jejunum

- Tongue

- Ileum

- Sigmoid colon

- Liver

- Submandibular gland

- Anal canal

- Parotid gland

- Descending colon

- Duodenum

- Esophagus

- Tranverse colon

- Pharynx

- Anus

- Sublingual gland

- Ascending colon

- Cecum

- Stomach

- Spleen

- Rectum

- Appendix

- Pancreas

Digestive System Anatomy Diagram (Text Version)

This diagram shows an anterior view of the head and torso of the human body with the anatomical organs and structures comprising the digestive system identified. From the top working clockwise. Located in the mouth or oral cavity are three glands which secrete saliva containing enzymes to aid in digestion these include: _______[Blank 1], ______[Blank 2], and the _________[Blank 3]. When the ingested food is ready to leave the mouth, it is transferred to the throat to swallow, the throat is also known as the ________[Blank 4]. The ________[Blank 5] is a muscular hollow organ which aids in the digestive process by breaking down food for digestion. While the _______[Blank 6] located under the left portion of the diaphragm, helps to filter blood. The ______[Blank 7] is an accessory organ responsible for producing a hormone known as insulin and insulin is critical in the metabolism of sugars. The large intestines have many structural components ________[Blank 8],_________[Blank 9], ________[Blank 10], ________[Blank 11], and _______[Blank 12] with these structures responsible for the final stage of digestion known as elimination. A small finger-like projections hangs from the cecum known as the ________[Blank 13] and this structure has a role in the development of the immune system in early human development. As a continuation of the sigmoid colon a hollow structure known as the _________[Blank 14] is identified. Next, is the final segment of the digestive system and is a structure measuring about 3 to 4 cm long known as the _______[Blank 15]. Fecal matter is expelled through the terminal opening in the digestive system called the ______[Blank 16]. The small intestines divided into three distinct parts; the is the third part ______[Blank 17], the _______[Blank 18] is the second part, and the _______[Blank 19] is the first part. The _______[Blank 20] is an accessory organ of digestion and is responsible for storing bile for when it is needed to breakdown fats in the process of digestion. The _______[Blank 21] located in the upper right side of the abdomen is responsible for producing the bile to send to the gallbladder for storage until it the bile is released. The _______[Blank 22] connects the pharynx to the stomach it is responsible for gently moving the food from the pharynx to the stomach. The _______[Blank 23] located in the mouth is responsible for moving the food around in the mouth during the chewing or mastication process. The _______[Blank 24] also known as the oral cavity contains the saliva glands, the teeth and tongue and begins the process of digestion.

Check your answers [1]

Activity source: Digestive System Anatomy by Gisele Tuzon, from Building a Medical Terminology Foundation, illustration from Anatomy and Physiology (OpenStax), licensed under CC BY 4.0./ Text version added.

Image Descriptions

Figure 12.2 image description: This diagram shows an anterior view of the structure of the mouth. The teeth, lips, tongue, gums and many other parts are labeled. Labels read (clockwise from top): superior lip, superior labial frenulum, gingivae, palatoglossal arch, fauces, palatopharyngeal arch, palatine tonsil, tongue, lingual frenulum, opening duct of submandibular gland, gingivae, inferior labial frenulum, inferior lip, oral vestibule, incisors, cuspid, premolars, molars, cheek, uvula, soft palate, hard palate. [Return to Figure 12.2].

Figure 12.3 image description: This diagram shows the structures of the tongue and lingual papillae. Labels read (from top): epiglottis, palatopharyngeal arch, palatine tonsil, lingual tonsil, palatoglossal arch, terminal sulcus, foliate papillae, circumvallate papilla, dorsum of tongue, fungiform papilla, filiform papilla. [Return to Figure 12.3].

Figure 12.4 image description: This diagram shows the esophagus, going from the mouth to the stomach. The upper and the lower esophageal sphincter are labeled. Labels read (from top): upper esophageal sphincter, trachea, esophagus, lower esophageal sphincter, stomach. [Return to Figure 12.4].

Figure 12.5 image description: This image shows a cross-section of the stomach, and the major parts: the cardia, fundus, body and pylorus are labeled. Labels read (from top of stomach): esophagus, muscular externa (longitudinal layer, circular layer, oblique layer), cardia, fundus, serosa, lesser and greater curvatures, lumen, rugae of mucosa, pyloric antrum, pyloric canal, pyloric sphincter valve at pylorus, duodenum. [Return to Figure 12.5].

Figure 12.6 image description: This diagram shows the small intestine. The different parts of the small intestine are labeled. Labels read (from top of small intestine): duodenum, jejunum, ileum, large intestine, rectum. [Return to Figure 12.6].

Figure 12.7 image description: This image shows the large intestine; the major parts of the large intestine are labeled. Labels read (from start of large intestinal tract): vermiform complex, cecum, ileum, ascending colon, transverse colon, right colic hepatic flexure, left colic splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, anal canal. [Return to Figure 12.7].

Figure 12.8 image description: This diagram shows the accessory organs of the digestive system. The liver, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder and their major parts are shown. Labels read: liver (right lobe, quadrate lobe, left lobe, caudate lobe), spleen, pancreas, pancreatic duct, gall bladder right hepatic duct, cystic duct, common hepatic duct, common bile duct, left hepatic duct. [Return to Figure 12.8].

Figure 12.9 image description: This figure shows the pancreas and its major parts Labels read (from left to right): common bile duct, head of pancreas, pancreatic duct, lobules, tail of pancreas. A magnified view of a small region of the pancreas shows the pancreatic islet cells, the acinar cells, exocrine cells, and the pancreatic duct. [Return to Figure 12.9].

Figure 12.10 image description: This figure shows the gallbladder and its major parts are labeled. Labels read (starting in gallbladder): body, fundus, neck, cystic duct, common hepatic duct, common bile duct, left and right hepatic ducts, liver. [Return to Figure 12.10].

Attribution

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Digestive System” In Building a Medical Terminology Foundation by Kimberlee Carter and Marie Rutherford, licensed under CC BY 4.0. / A derivative of Betts et al., which can be accessed for free from Anatomy and Physiology (OpenStax). Adaptations: dividing Digestive System chapter content into sub-chapters.

-

↵

Check your answers: Digestive System Anatomy Diagram (Text Version)

This diagram shows an anterior vies of the head and torso of the human body with the anatomical organs and structures comprising the digestive system identified. From the top working clockwise Located in the mouth or oral cavity are three glands which secrete saliva containing enzymes to aid in digestion these include: parotid gland, sublingual gland, and the submandibular gland. When the ingested food is ready to leave the mouth, it is transferred to the throat to swallow, the throat is also known as the pharynx. The stomach is a muscular hollow organ which aids in the digestive process by breaking down food for digestion. While the spleen located under the left portion of the diaphragm, helps to filter blood. The pancreas is an accessory organ responsible for producing a hormone known as insulin and insulin is critical in the metabolism of sugars. The large intestines have many structural components transverse colon, ascending colon, descending colon, cecum, and sigmoid colon with these structures responsible for the final stage of digestion known as elimination. A small finger-like projections hangs from the cecum known as the appendix and this structure has a role in the development of the immune system in early human development. As a continuation of the sigmoid colon a hollow structure known as the rectum is identified. Next, is the final segment of the digestive system and is a structure measuring about 3 to 4 cm long known as the anal canal. Fecal matter is expelled through the terminal opening in the digestive system called the anus. The small intestines divided into three distinct parts; the is the third part ileum, the jejunum is the second part, and the duodenum is the first part. The gall bladder is an accessory organ of digestion and is responsible for storing bile for when it is needed to breakdown fats in the process of digestion. The liver located in the upper right side of the abdomen is responsible for producing the bile to send to the gallbladder for storage until it the bile is released. The esophagus connects the pharynx to the stomach it is responsible for gently moving the food from the pharynx to the stomach. The tongue located in the mouth is responsible for moving the food around in the mouth during the chewing or mastication process. The mouth also known as the oral cavity contains the saliva glands, the teeth and tongue and begins the process of digestion.

lips of the mouth

The inside of your nose.

a pair of soft tissue masses located at the rear of the throat (pharynx)

collection of lymphatic tissue located in the lamina propria of the root of the tongue

Cells arranged in layers upon a basal membrane

to secrete externally, directly or through a duct

The sugars, starches and fibers found in fruits, grains, vegetables and milk products.

A band of smooth muscle at the junction between the pylorus of the stomach and the duodenum of the small intestine

Curved outwards

Fatty tissue that stretches over the abdomen, plays a role in immune response and the growth of certain cancers

situated nearer to the center of the body or the point of attachment

Away from the center of the body or from the point of attachment

Resembling lymph or lymphatic tissues

A by-product of the body's metabolism

A square or rectangular.

The process of breaking down the fat into smaller blood cells which makes it easy for enzymes to function and digest food.

A concave region where blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves also enter the lungs

A sac-like enlargement of a canal or duct

A part of a hollow organ