16.2 – Anatomy (Structures) of the Nervous System

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

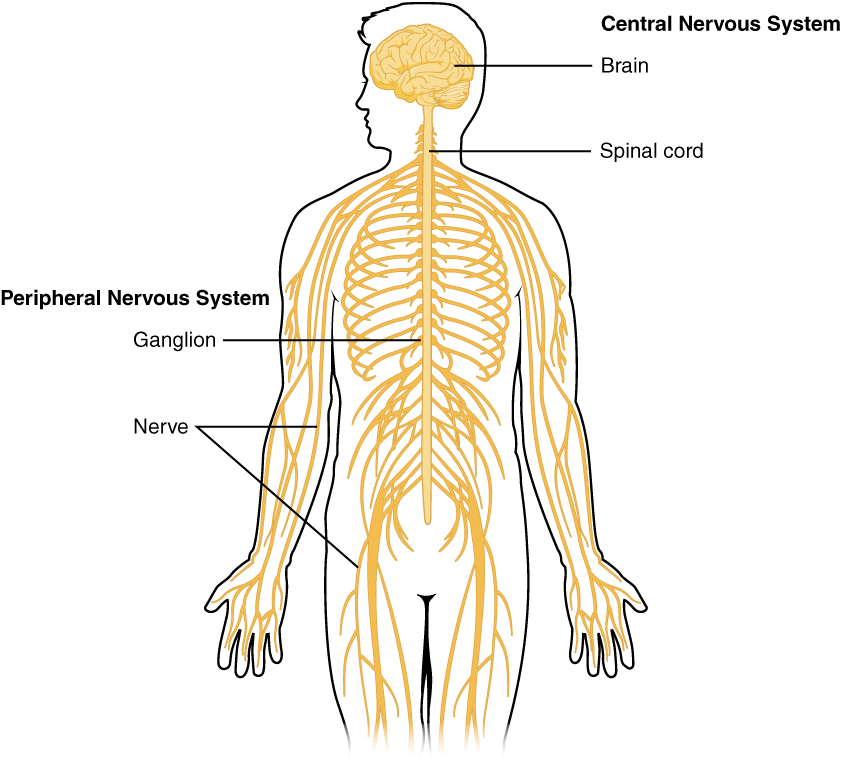

The nervous system can be divided into two major regions: the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) is the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is everything else (see Figure 16.1). The brain is contained within the cranial cavity of the skull, and the spinal cord is contained within the vertebral cavity of the vertebral column. It is a bit of an oversimplification to say that the CNS is what is inside these two cavities and the peripheral nervous system is outside of them, but that is one way to start to think about it. In actuality, there are some elements of the peripheral nervous system that are within the cranial or vertebral cavities. The peripheral nervous system is so named because it is on the periphery—meaning beyond the brain and spinal cord. Depending on different aspects of the nervous system, the dividing line between central and peripheral is not necessarily universal.

Nervous tissue, present in both the CNS and PNS, contains two basic types of cells: neurons and glial cells. Neurons are the primary type of cell that most anyone associates with the nervous system. They are responsible for the computation and communication that the nervous system provides. They are electrically active and release chemical signals to target cells. Glial cells, or glia, are known to play a supporting role for nervous tissue. Ongoing research pursues an expanded role that glial cells might play in signaling, but neurons are still considered the basis of this function. Neurons are important, but without glial support they would not be able to perform their function. A glial cell is one of a variety of cells that provide a framework of tissue that supports the neurons and their activities. The neuron is the more functionally important of the two, in terms of the communicative function of the nervous system. To describe the functional divisions of the nervous system, it is important to understand the structure of a neuron.

Did You Know 1?

The brain has over 100 billion neurons.

Neurons are cells and therefore have a soma, or cell body, but they also have extensions of the cell; each extension is generally referred to as a process. There is one important process that every neuron has called an axon, which is the fiber that connects a neuron with its target. Another type of process that branches off from the soma is the dendrite. Dendrites are responsible for receiving most of the input from other neurons.

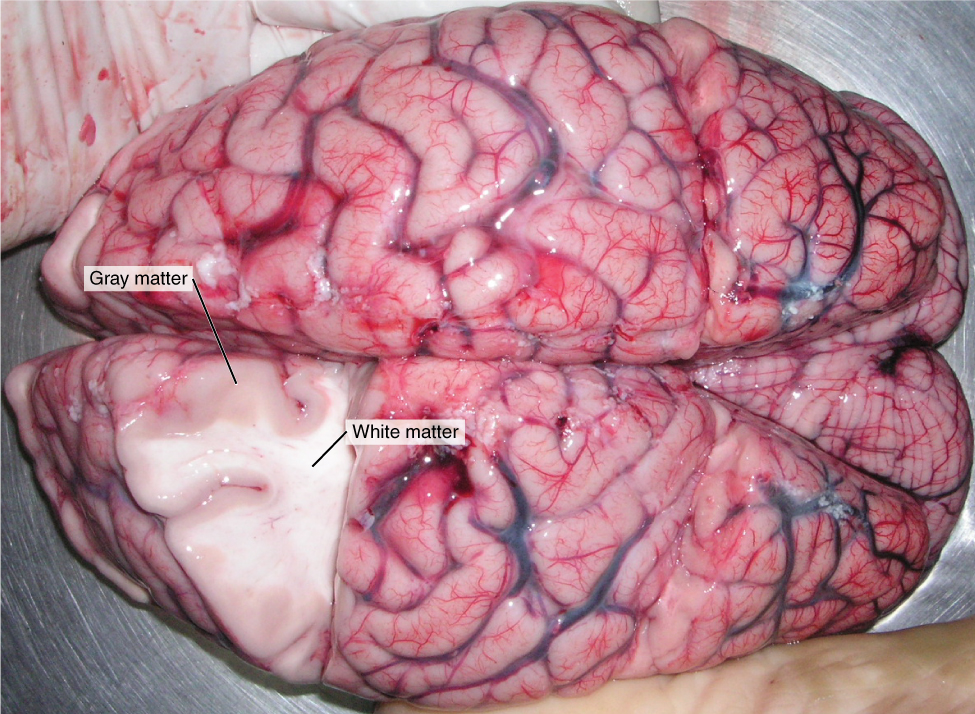

Looking at nervous tissue, there are regions that predominantly contain cell bodies and regions that are largely composed of just axons. These two regions within nervous system structures are often referred to as gray matter (the regions with many cell bodies and dendrites) or white matter (the regions with many axons). Figure 16.2 demonstrates the appearance of these regions in the brain and spinal cord. The colours ascribed to these regions are what would be seen in “fresh,” or unstained, nervous tissue. Gray matter is not necessarily gray. It can be pinkish because of blood content, or even slightly tan, depending on how long the tissue has been preserved. White matter is white because axons are insulated by a lipid-rich substance called myelin. Lipids can appear as white (“fatty”) material, much like the fat on a raw piece of chicken or beef. Actually, gray matter may have that colour ascribed to it because next to the white matter, it is just darker—hence, gray.

The distinction between gray matter and white matter is most often applied to central nervous tissue, which has large regions that can be seen with the unaided eye. When looking at peripheral structures, often a microscope is used and the tissue is stained with artificial colours. That is not to say that central nervous tissue cannot be stained and viewed under a microscope, but unstained tissue is most likely from the CNS—for example, a frontal section of the brain or cross section of the spinal cord.

The Adult Brain

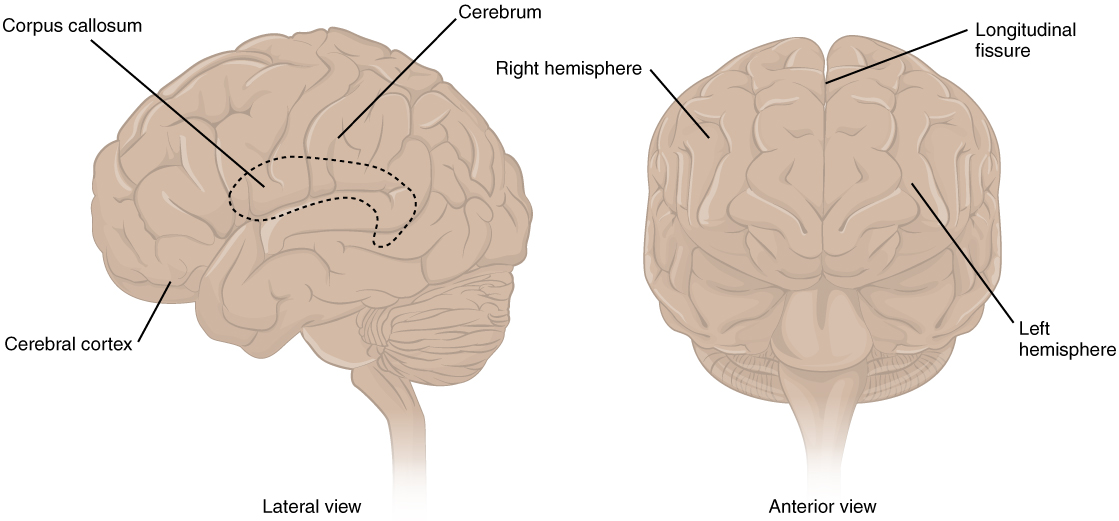

The adult brain is separated into four major regions: the cerebrum, the diencephalon, the brain stem, and the cerebellum. The cerebrum is the largest portion and contains the cerebral cortex and subcortical nuclei. It is divided into two halves by the longitudinal fissure.

The Cerebrum

The iconic gray mantle of the human brain, which appears to make up most of the mass of the brain, is the cerebrum (see Figure 16.3). The wrinkled portion is the cerebral cortex, and the rest of the structure is beneath that outer covering. There is a large separation between the two sides of the cerebrum called the longitudinal fissure. It separates the cerebrum into two distinct halves, a right and left cerebral hemisphere. Deep within the cerebrum, the white matter of the corpus callosum provides the major pathway for communication between the two hemispheres of the cerebral cortex.

Did You Know 2?

The brain is about 75% water and is the fattest organ in the body.

Many of the higher neurological functions, such as memory, emotion, and consciousness, are the result of cerebral function. The complexity of the cerebrum is different across vertebrate species. The cerebrum of the most primitive vertebrates is not much more than the connection for the sense of smell. In mammals, the cerebrum comprises the outer gray matter that is the cortex (from the Latin word meaning “bark of a tree”) and several deep nuclei that belong to three important functional groups. The basal nuclei are responsible for cognitive processing, the most important function being that associated with planning movements. The basal forebrain contains nuclei that are important in learning and memory. The limbic cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex that part of the limbic system, a collection of structures involved in emotion, memory, and behavior.

Cerebral Cortex

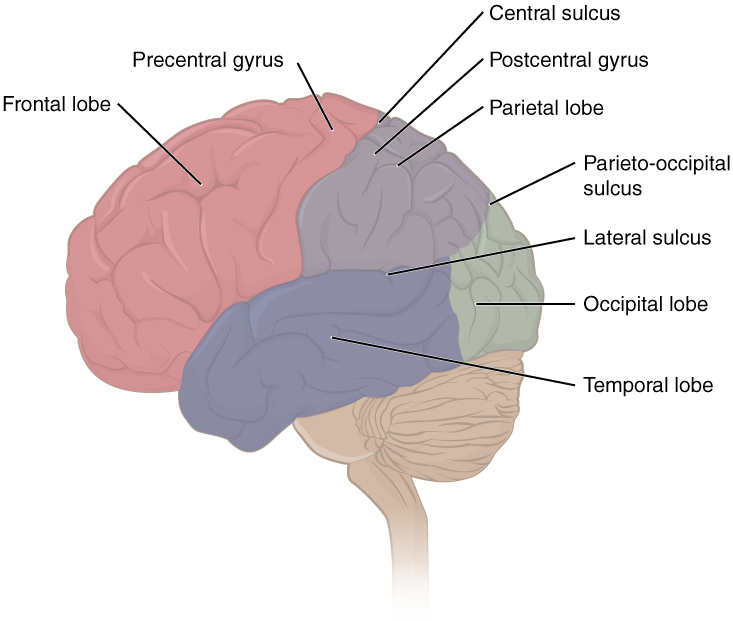

The cerebrum is covered by a continuous layer of gray matter that wraps around either side of the forebrain—the cerebral cortex. This thin, extensive region of wrinkled gray matter is responsible for the higher functions of the nervous system. A gyrus (plural = gyri) is the ridge of one of those wrinkles, and a sulcus (plural = sulci) is the groove between two gyri. The pattern of these folds of tissue indicates specific regions of the cerebral cortex.

The head is limited by the size of the birth canal, and the brain must fit inside the cranial cavity of the skull. Extensive folding in the cerebral cortex enables more gray matter to fit into this limited space. If the gray matter of the cortex were peeled off of the cerebrum and laid out flat, its surface area would be roughly equal to one square meter.

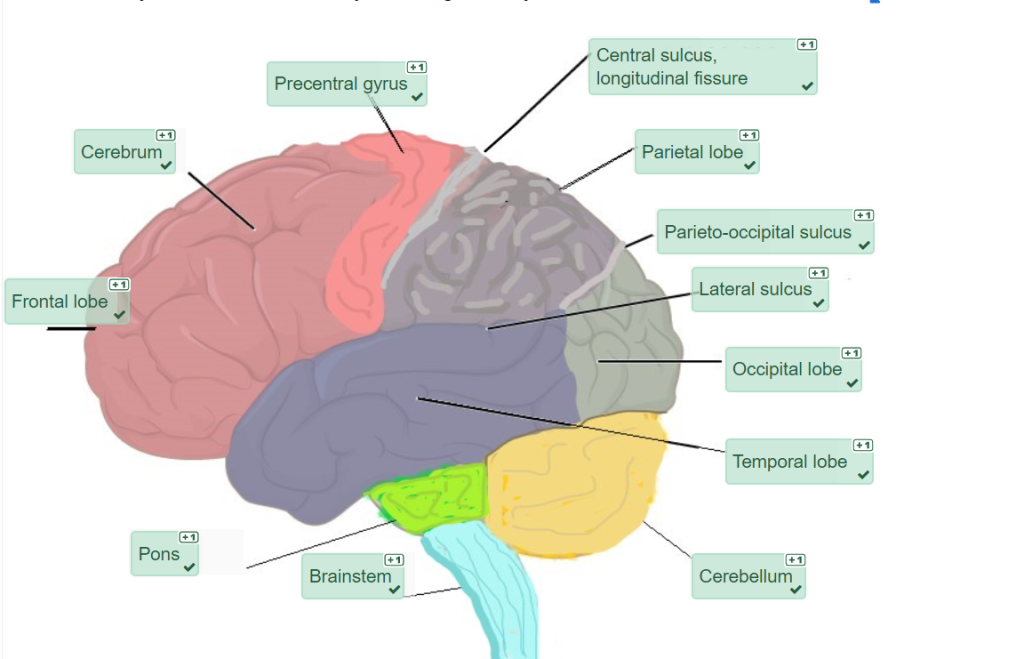

The folding of the cortex maximizes the amount of gray matter in the cranial cavity. During embryonic development, as the telencephalon expands within the skull, the brain goes through a regular course of growth that results in everyone’s brain having a similar pattern of folds. The surface of the brain can be mapped on the basis of the locations of large gyri and sulci. Using these landmarks, the cortex can be separated into four major regions, or lobes (see Figure 16.4). The lateral sulcus that separates the temporal lobe from the other regions is one such landmark. Superior to the lateral sulcus are the parietal lobe and frontal lobe, which are separated from each other by the central sulcus. The posterior region of the cortex is the occipital lobe, which has no obvious anatomical border between it and the parietal or temporal lobes on the lateral surface of the brain. From the medial surface, an obvious landmark separating the parietal and occipital lobes is called the parieto-occipital sulcus. The fact that there is no obvious anatomical border between these lobes is consistent with the functions of these regions being interrelated.

Concept Check 1

- Identify the two major divisions of the nervous system.

- Describe the cerebral cortex.

- What are the halves of the cerebrum know as?

The Diencephalon

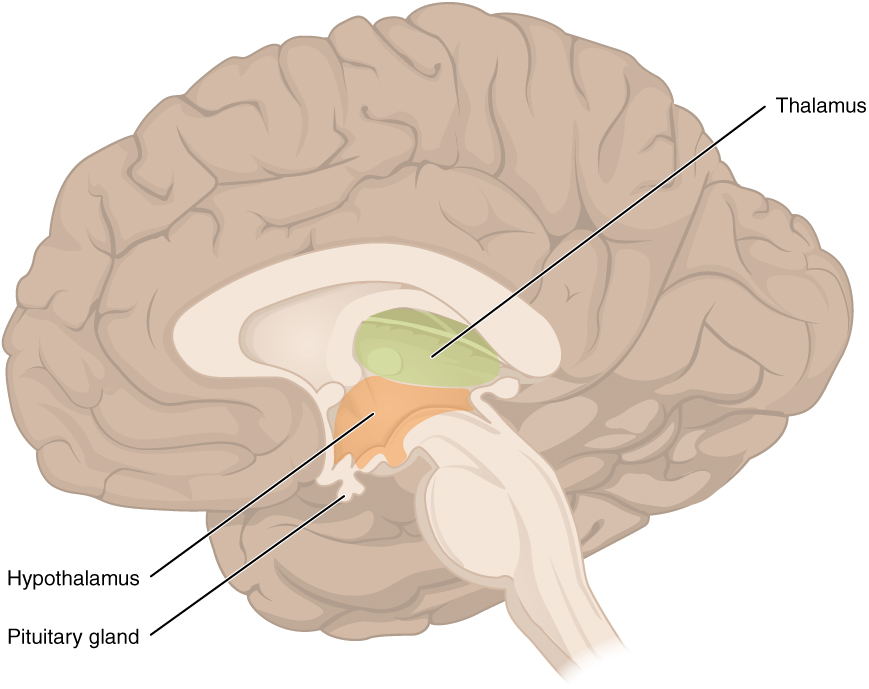

The diencephalon is deep beneath the cerebrum and constitutes the walls of the third ventricle. The diencephalon can be described as any region of the brain with “thalamus” in its name. The two major regions of the diencephalon are the thalamus itself and the hypothalamus (see Figure 16.5). There are other structures, such as the epithalamus, which contains the pineal gland, or the subthalamus, which includes the subthalamic nucleus that is part of the basal nuclei.

Thalamus

The thalamus is a collection of nuclei that relay information between the cerebral cortex and the periphery, spinal cord, or brain stem. All sensory information, except for the sense of smell, passes through the thalamus before processing by the cortex. For example, the portion of the thalamus that receives visual information will influence what visual stimuli are important, or what receives attention.

The cerebrum also sends information down to the thalamus, which usually communicates motor commands. This involves interactions with the cerebellum and other nuclei in the brain stem. The cerebrum interacts with the basal nuclei, which involves connections with the thalamus. The primary output of the basal nuclei is to the thalamus, which relays that output to the cerebral cortex. The cortex also sends information to the thalamus that will then influence the effects of the basal nuclei.

Hypothalamus

Inferior and slightly anterior to the thalamus is the hypothalamus, the other major region of the diencephalon. The hypothalamus is a collection of nuclei that are largely involved in regulating homeostasis. The hypothalamus is the executive region in charge of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system through its regulation of the anterior pituitary gland. Other parts of the hypothalamus are involved in memory and emotion as part of the limbic system.

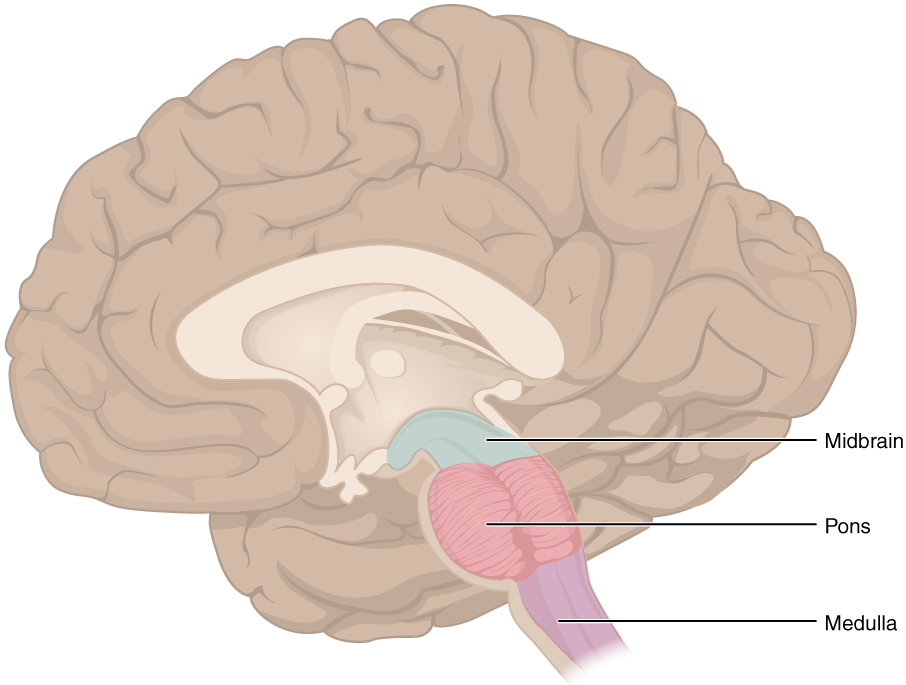

Brain Stem

The midbrain and hindbrain (composed of the pons and the medulla) are collectively referred to as the brain stem (see Figure 16.6). The structure emerges from the ventral surface of the forebrain as a tapering cone that connects the brain to the spinal cord. Attached to the brain stem, but considered a separate region of the adult brain, is the cerebellum. The midbrain coordinates sensory representations of the visual, auditory, and somatosensory perceptual spaces. The pons is the main connection with the cerebellum. The pons and the medulla regulate several crucial functions, including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and rates.

The cranial nerves connect through the brain stem and provide the brain with the sensory input and motor output associated with the head and neck, including most of the special senses. The major ascending and descending pathways between the spinal cord and brain, specifically the cerebrum, pass through the brain stem.

Midbrain

One of the original regions of the embryonic brain, the midbrain is a small region between the thalamus and pons. It is separated into the tectum and tegmentum, from the Latin words for roof and floor, respectively. The cerebral aqueduct passes through the center of the midbrain, such that these regions are the roof and floor of that canal.

Pons

The word pons comes from the Latin word for bridge. It is visible on the anterior surface of the brain stem as the thick bundle of white matter attached to the cerebellum. The pons is the main connection between the cerebellum and the brain stem. The bridge-like white matter is only the anterior surface of the pons; the gray matter beneath that is a continuation of the tegmentum from the midbrain. Gray matter in the tegmentum region of the pons contains neurons receiving descending input from the forebrain that is sent to the cerebellum.

Medulla

The medulla is the region known as the myelencephalon in the embryonic brain. The initial portion of the name, “myel,” refers to the significant white matter found in this region—especially on its exterior, which is continuous with the white matter of the spinal cord. The tegmentum of the midbrain and pons continues into the medulla because this gray matter is responsible for processing cranial nerve information. A diffuse region of gray matter throughout the brain stem, known as the reticular formation, is related to sleep and wakefulness, such as general brain activity and attention.

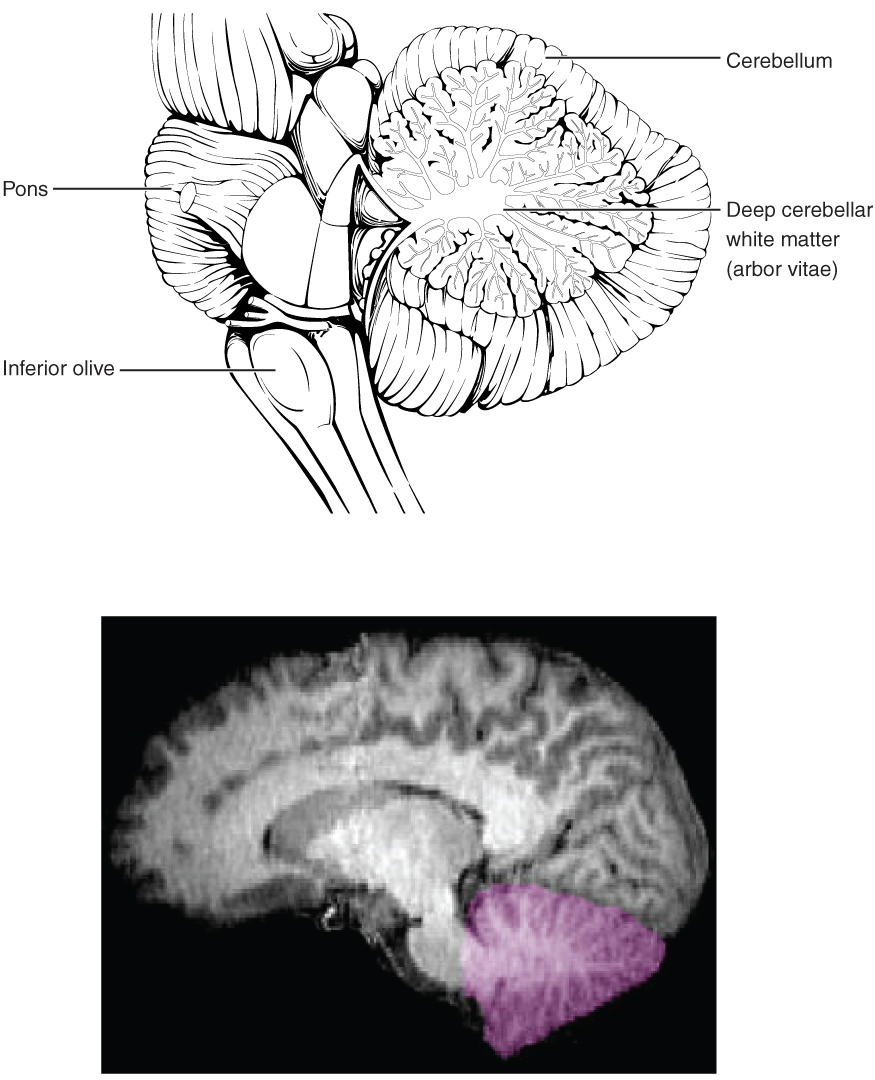

The Cerebellum

The cerebellum, as the name suggests, is the “little brain.” It is covered in gyri and sulci like the cerebrum, and looks like a miniature version of that part of the brain (see Figure 16.7). The cerebellum is largely responsible for comparing information from the cerebrum with sensory feedback from the periphery through the spinal cord. It accounts for approximately 10 percent of the mass of the brain.

Concept Check 2

- What is the primary processing purpose of the medulla?

- Identify the structure in the brain responsible for sensory feedback through the spinal cord. Suggest what may happen if this function failed.

The Spinal Cord

The description of the CNS is concentrated on the structures of the brain, but the spinal cord is another major organ of the system. Whereas the brain develops out of expansions of the neural tube into primary and then secondary vesicles, the spinal cord maintains the tube structure and is only specialized into certain regions. As the spinal cord continues to develop in the newborn, anatomical features mark its surface. The anterior midline is marked by the anterior median fissure, and the posterior midline is marked by the posterior median sulcus. Axons enter the posterior side through the dorsal (posterior) nerve root, which marks the posterolateral sulcus on either side. The axons emerging from the anterior side do so through the ventral (anterior) nerve root. Note that it is common to see the terms dorsal (dorsal = “back”) and ventral (ventral = “belly”) used interchangeably with posterior and anterior, particularly in reference to nerves and the structures of the spinal cord. You should learn to be comfortable with both.

On the whole, the posterior regions are responsible for sensory functions and the anterior regions are associated with motor functions. This comes from the initial development of the spinal cord, which is divided into the basal plate and the alar plate. The basal plate is closest to the ventral midline of the neural tube, which will become the anterior face of the spinal cord and gives rise to motor neurons. The alar plate is on the dorsal side of the neural tube and gives rise to neurons that will receive sensory input from the periphery.

The length of the spinal cord is divided into regions that correspond to the regions of the vertebral column. The name of a spinal cord region corresponds to the level at which spinal nerves pass through the intervertebral foramina. Immediately adjacent to the brain stem is the following divisions of the spinal cord:

- cervical region

- thoracic region

- lumbar region

- sacral region

Did You Know 3?

The bundle of nerve fibers making up the spinal cord is no thicker than the human thumb.

The spinal cord is not the full length of the vertebral column because the spinal cord does not grow significantly longer after the first or second year, but the skeleton continues to grow. The nerves that emerge from the spinal cord pass through the intervertebral formina at the respective levels. As the vertebral column grows, these nerves grow with it and result in a long bundle of nerves that resembles a horse’s tail and is named the cauda equina. The sacral spinal cord is at the level of the upper lumbar vertebral bones. The spinal nerves extend from their various levels to the proper level of the vertebral column.

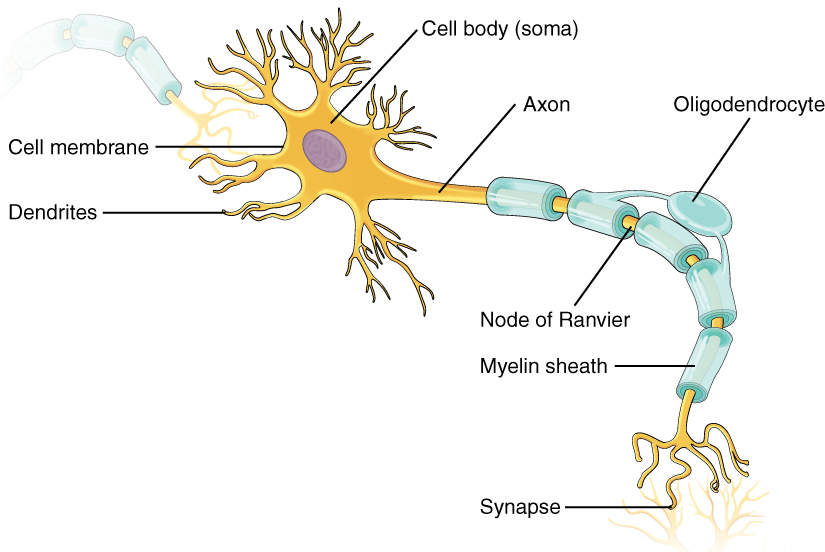

Neurons

Neurons are the cells considered to be the basis of nervous tissue. They are responsible for the electrical signals that communicate information about sensations, and that produce movements in response to those stimuli, along with inducing thought processes within the brain. An important part of the function of neurons is in their structure, or shape. The three-dimensional shape of these cells makes the immense numbers of connections within the nervous system possible.

Parts of a Neuron

As you learned in the first section, the main part of a neuron is the cell body, which is also known as the soma (soma = “body”). The cell body contains the nucleus and most of the major organelles. But what makes neurons special is that they have many extensions of their cell membranes, which are generally referred to as processes. Neurons are usually described as having one, and only one, axon—a fiber that emerges from the cell body and projects to target cells. That single axon can branch repeatedly to communicate with many target cells. It is the axon that propagates the nerve impulse, which is communicated to one or more cells. The other processes of the neuron are dendrites, which receive information from other neurons at specialized areas of contact called synapses. The dendrites are usually highly branched processes, providing locations for other neurons to communicate with the cell body. Information flows through a neuron from the dendrites, across the cell body, and down the axon. This gives the neuron a polarity—meaning that information flows in this one direction. Figure 16.8 shows the relationship of these parts to one another.

Where the axon emerges from the cell body, there is a special region referred to as the axon hillock. This is a tapering of the cell body toward the axon fiber. Within the axon hillock, the cytoplasm changes to a solution of limited components called axoplasm. Because the axon hillock represents the beginning of the axon, it is also referred to as the initial segment.

Many axons are wrapped by an insulating substance called myelin, which is actually made from glial cells. Myelin acts as insulation much like the plastic or rubber that is used to insulate electrical wires. A key difference between myelin and the insulation on a wire is that there are gaps in the myelin covering of an axon. Each gap is called a node of Ranvier and is important to the way that electrical signals travel down the axon. The length of the axon between each gap, which is wrapped in myelin, is referred to as an axon segment. At the end of the axon is the axon terminal, where there are usually several branches extending toward the target cell, each of which ends in an enlargement called a synaptic end bulb. These bulbs are what make the connection with the target cell at the synapse.

Types of Neurons

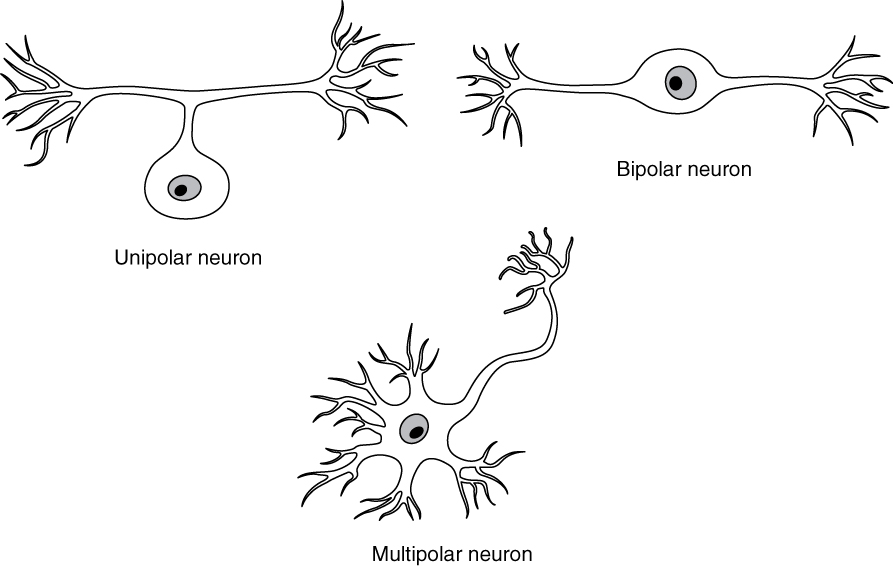

There are many neurons in the nervous system—a number in the trillions. And there are many different types of neurons. They can be classified by many different criteria. The first way to classify them is by the number of processes attached to the cell body. Using the standard model of neurons, one of these processes is the axon, and the rest are dendrites. Because information flows through the neuron from dendrites or cell bodies toward the axon, these names are based on the neuron’s polarity (see Figure 16.9).

Unipolar cells have only one process emerging from the cell. True unipolar cells are only found in invertebrate animals, so the unipolar cells in humans are more appropriately called “pseudo-unipolar” cells. Invertebrate unipolar cells do not have dendrites.

Bipolar cells have two processes, which extend from each end of the cell body, opposite to each other. One is the axon and one the dendrite. Bipolar cells are not very common. They are found mainly in the olfactory epithelium (where smell stimuli are sensed), and as part of the retina.

Multipolar neurons are all of the neurons that are not unipolar or bipolar. They have one axon and two or more dendrites (usually many more). With the exception of the unipolar sensory ganglion cells, and the two specific bipolar cells mentioned above, all other neurons are multipolar.

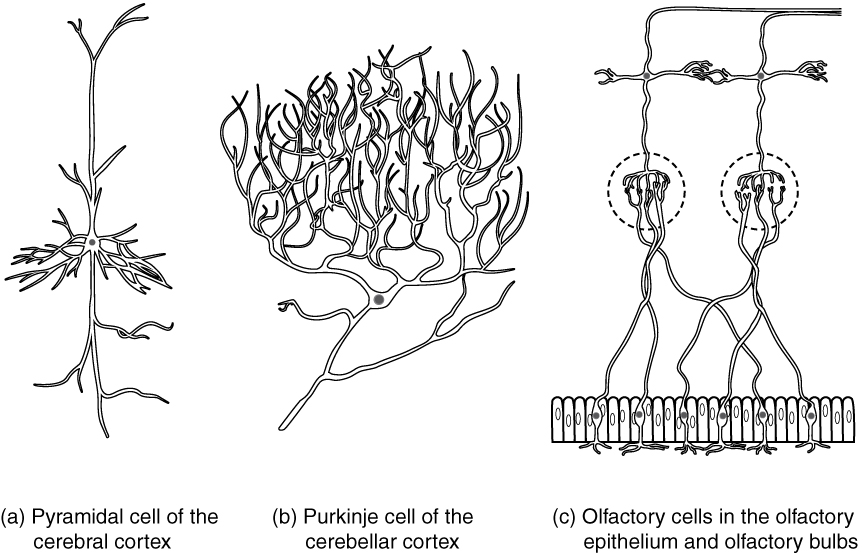

Neurons can also be classified on the basis of where they are found, who found them, what they do, or even what chemicals they use to communicate with each other. Some neurons referred to in this section on the nervous system are named on the basis of those sorts of classifications (see Figure 16.10). For example, a multipolar neuron that has a very important role to play in a part of the brain called the cerebellum is known as a Purkinje (commonly pronounced per-KIN-gee) cell. It is named after the anatomist who discovered it (Jan Evangilista Purkinje, 1787–1869).

Glial Cells

Glial cells, or neuroglia or simply glia, are the other type of cell found in nervous tissue. They are considered to be supporting cells, and many functions are directed at helping neurons complete their function for communication. The name glia comes from the Greek word that means “glue,” and was coined by the German pathologist Rudolph Virchow, who wrote in 1856: “This connective substance, which is in the brain, the spinal cord, and the special sense nerves, is a kind of glue (neuroglia) in which the nervous elements are planted.” Today, research into nervous tissue has shown that there are many deeper roles that these cells play. And research may find much more about them in the future.

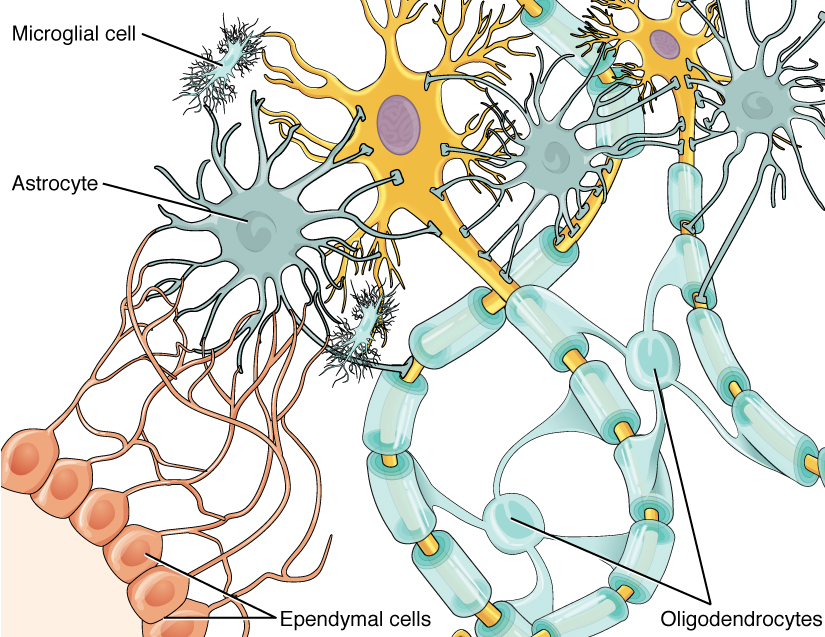

There are six types of glial cells. Four of them are found in the CNS and two are found in the PNS. Table 16.1 outlines some common characteristics and functions.

| CNS Glia | PNS Glia | Basic Function |

|---|---|---|

| Astrocyte | Satellite cell | Support |

| Oligodendrocyte | Schwann cell | Insulation, myelination |

| Microglia | – | Immune surveillance and phagocytosis |

| Ependymal cell | – | Creating CSF |

Glial Cells of the CNS

One cell providing support to neurons of the CNS is the astrocyte, so named because it appears to be star-shaped under the microscope (astro- = “star”). Astrocytes have many processes extending from their main cell body (not axons or dendrites like neurons, just cell extensions). Those processes extend to interact with neurons, blood vessels, or the connective tissue covering the CNS that is called the pia mater (see Figure 16.11). Generally, they are supporting cells for the neurons in the central nervous system. Some ways in which they support neurons in the central nervous system are by maintaining the concentration of chemicals in the extracellular space, removing excess signaling molecules, reacting to tissue damage, and contributing to the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The blood-brain barrier is a physiological barrier that keeps many substances that circulate in the rest of the body from getting into the central nervous system, restricting what can cross from circulating blood into the CNS. Nutrient molecules, such as glucose or amino acids, can pass through the BBB, but other molecules cannot. This actually causes problems with drug delivery to the CNS. Pharmaceutical companies are challenged to design drugs that can cross the BBB as well as have an effect on the nervous system.

Like a few other parts of the body, the brain has a privileged blood supply. Very little can pass through by diffusion. Most substances that cross the wall of a blood vessel into the CNS must do so through an active transport process. Because of this, only specific types of molecules can enter the CNS. Glucose—the primary energy source—is allowed, as are amino acids. Water and some other small particles, like gases and ions, can enter. But most everything else cannot, including white blood cells, which are one of the body’s main lines of defense. While this barrier protects the CNS from exposure to toxic or pathogenic substances, it also keeps out the cells that could protect the brain and spinal cord from disease and damage. The BBB also makes it harder for pharmaceuticals to be developed that can affect the nervous system. Aside from finding efficacious substances, the means of delivery is also crucial.

Oligodendrocyte, sometimes called just “oligo,” which is the glial cell type that insulates axons in the CNS. The name means “cell of a few branches” (oligo- = “few”; dendro- = “branches”; -cyte = “cell”). There are a few processes that extend from the cell body. Each one reaches out and surrounds an axon to insulate it in myelin.

Microglia are, as the name implies, smaller than most of the other glial cells. Ongoing research into these cells, although not entirely conclusive, suggests that they may originate as white blood cells, called macrophages, that become part of the CNS during early development. While their origin is not conclusively determined, their function is related to what macrophages do in the rest of the body. When macrophages encounter diseased or damaged cells in the rest of the body, they ingest and digest those cells or the pathogens that cause disease. Microglia are the cells in the CNS that can do this in normal, healthy tissue, and they are therefore also referred to as CNS-resident macrophages.

The ependymal cell is a glial cell that filters blood to make cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the fluid that circulates through the CNS. Because of the privileged blood supply inherent in the BBB, the extracellular space in nervous tissue does not easily exchange components with the blood. Ependymal cells line each ventricle, one of four central cavities that are remnants of the hollow center of the neural tube formed during the embryonic development of the brain. They also have cilia on their apical surface to help move the CSF through the ventricular space. The relationship of these glial cells to the structure of the CNS is seen in Figure 16.11.

Glial Cells of the PNS

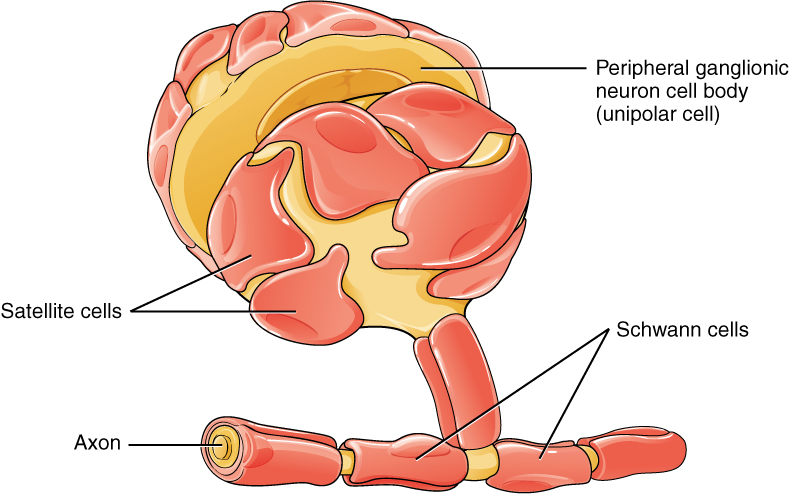

One of the two types of glial cells found in the PNS is the satellite cell. Satellite cells are found in sensory and autonomic ganglia, where they surround the cell bodies of neurons. This accounts for the name, based on their appearance under the microscope. They provide support, performing similar functions in the periphery as astrocytes do in the CNS—except, of course, for establishing the BBB.

The second type of glial cell is the Schwann cell, which insulate axons with myelin in the periphery. Schwann cells are different than oligodendrocytes, in that a Schwann cell wraps around a portion of only one axon segment and no others. Oligodendrocytes have processes that reach out to multiple axon segments, whereas the entire Schwann cell surrounds just one axon segment. The nucleus and cytoplasm of the Schwann cell are on the edge of the myelin sheath. The relationship of these two types of glial cells to ganglia and nerves in the PNS is seen in Figure 16.12.

Myelin

The appearance of the myelin sheath can be thought of as similar to the pastry wrapped around a hot dog for “pigs in a blanket” or a similar food. The glial cell is wrapped around the axon several times with little to no cytoplasm between the glial cell layers. For oligodendrocytes, the rest of the cell is separate from the myelin sheath as a cell process extends back toward the cell body. A few other processes provide the same insulation for other axon segments in the area. For Schwann cells, the outermost layer of the cell membrane contains cytoplasm and the nucleus of the cell as a bulge on one side of the myelin sheath. During development, the glial cell is loosely or incompletely wrapped around the axon. The edges of this loose enclosure extend toward each other, and one end tucks under the other. The inner edge wraps around the axon, creating several layers, and the other edge closes around the outside so that the axon is completely enclosed.

Check Your Knowledge of the Nervous System Brain Anatomy

Nervous System Brain Anatomy Labeling Activity

Nervous System Brain Anatomy Labeling Activity (Text Version)

Label the diagram with correct words listed below:

- Central sulcus, longitudinal fissure

- Pons

- Precentral gyrus

- Frontal Lobe

- Occipital lobe

- Cerebrum

- Cerebellum

- Lateral Sulcus

- Brainstem

- Parietal lobe

- Temporal lobe

- parieto-occipital sulcus

Nervous System Brain Anatomy Labeling Activity Diagram (Text Version)

This diagram shows the lateral view of the brain and the major lobes which are labeled. From the front of the brain (left): ______[Blank 1} is responsible for thought processes, followed by a raised surface area known as ______[Blank 2], a deep groove known as the ______[Blank 3], and another raised area knowns as ______[Blank 4]. The ______[Blank 5] is responsible for processes senses such as the sense of touch, followed by the _____[Blank 6] which is another deep groove on the surface of the brain. The _____[Blank 7] processes visual fields and the _______[Blank 8], which is responsible for memory capacity. The ____ [Blank 9] is responsible for balance, followed by the _____[Blank 10], which is often referred to as the medulla oblongata, and finally is the ____,[Blank 11] which is known as the bridge connecting the cerebrum to the cerebellum. The _______ [Blank 12] is a deep groove on the surface of the cerebrum.

Check your answers [1]

Activity source: Nervous System Brain Anatomy labeling activity by Sheila Bellefeuille from Building a Medical Terminology Foundation, illustration from Anatomy and Physiology (OpenStax), licensed under CC BY 4.0./ Text version added.

Image Descriptions

Figure 16.1 image description: This diagram shows a silhouette of a human highlighting the nervous system. The central nervous system is composed of the brain and spinal cord. The brain is a large mass of ridged and striated tissue within the head. The spinal cord extends down from the brain and travels through the torso, ending in the pelvis. Pairs of enlarged nervous tissue, labeled ganglia, flank the spinal cord as it travels through the rib area. The ganglia are part of the peripheral nervous system, along with the many thread-like nerves that radiate from the spinal cord and ganglia through the arms, abdomen and legs. [Return to Figure 16.1].

Figure 16.2 image description: This photo shows an enlarged view of the dorsal side of a human brain. The right side of the occipital lobe has been shaved to reveal the white and gray matter beneath the surface blood vessels. The white matter branches though the shaved section like the limbs of a tree. The gray matter branches and curves on outside of the white matter, creating a buffer between the outer edges of the occipital lobe and the internal white matter. [Return to Figure 16.2].

Figure 16.3 image description: This figure shows the lateral view on the left panel and anterior view on the right panel of the brain. The major parts including the cerebrum are labeled. Lateral view labels (clockwise from top) read: cerebrum, cerebral cortex, corpus callosum (located on the interior of the brain). Anterior view labels indicate the right and left hemispheres, and the longitudinal fissure between them. [Return to Figure 16.3].

Figure 16.4 image description: This figure shows the lateral view of the brain and the major lobes are labeled. From the front of the brain (left) labels read: frontal lobe, precentral gyrus, central sulcus, postcentral gyrus, parietal lobe, lateral sulcus, occipital lobe, temporal lobe. [Return to Figure 16.4].

Figure 16.5 image description: This figure shows the location of the thalamus, hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain. Each part is labelled respectively. The thalamus is located in the midsection of the brain. The hypothalamus is located below the thalamus, and the pituitary gland below that. [Return to Figure 16.5].

Figure 16.6 image description: This figure shows the location of the midbrain, pons and the medulla in the brain that make up the brain stem. The midbrain is located at the top, the pons is located beneath that, and the medulla is the lowest most point of the brain stem. [Return to Figure 16.6].

Figure 16.7 image description: This figure shows the location of the cerebellum in the brain which is located on the posterior surface of the brain stem. Labels read (top, left): pons, inferior olive, (top, right) cerebellum, deep cerebellar white matter (arbor vitae). In the top panel, a lateral view labels the location of the cerebellum and the deep cerebellar white matter. In the bottom panel, a photograph of a brain, with the cerebellum in pink is shown. [Return to Figure 16.7].

Figure 16.8 image description: This illustration shows the anatomy of a neuron. The neuron has a very irregular cell body (soma) containing a purple nucleus. There are six projections protruding from the top, bottom and left side of the cell body. Each of the projections branches many times, forming small, tree-shaped structures protruding from the cell body. The right side of the cell body tapers into a long cord called the axon. The axon is insulated by segments of myelin sheath, which resemble a semitransparent toilet paper roll wound around the axon. The myelin sheath is not continuous, but is separated into equally spaced segments. The bare axon segments between the sheath segments are called nodes of Ranvier. An oligodendrocyte is reaching its two arm like projections onto two myelin sheath segments. The axon branches many times at its end, where it connects to the dendrites of another neuron. Each connection between an axon branch and a dendrite is called a synapse. The cell membrane completely surrounds the cell body, dendrites, and its axon. The axon of another nerve is seen in the upper left of the diagram connecting with the dendrites of the central neuron. [Return to Figure 16.8].

Figure 16.9 image description: Three illustrations show some of the possible shapes that neurons can take. In the unipolar neuron, the dendrite enters from the left and merges with the axon into a common pathway, which is connected to the cell body. The axon leaves the cell body through the common pathway, the branches off to the right, in the opposite direction as the dendrite. Therefore, this neuron is T shaped. In the bipolar neuron, the dendrite enters into the left side of the cell body while the axon emerges from the opposite (right) side. In a multipolar neuron, multiple dendrites enter into the cell body. The only part of the cell body that does not have dendrites is the part that elongates into the axon. [Return to Figure 16.9].

Figure 16.10 image description: This diagram contains three black and white drawings of more specialized nerve cells. Part A shows a pyramidal cell of the cerebral cortex, which has two, long, nerve tracts attached to the top and bottom of the cell body. However, the cell body also has many shorter dendrites projecting out a short distance from the cell body. Part B shows a Purkinje cell of the cerebellar cortex. This cell has a single, long, nerve tract entering the bottom of the cell body. Two large nerve tracts leave the top of the cell body but immediately branch many times to form a large web of nerve fibers. Therefore, the purkinje cell somewhat resembles a shrub or coral in shape. Part C shows the olfactory cells in the olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulbs. It contains several cell groups linked together. At the bottom, there is a row of olfactory epithelial cells that are tightly packed, side-by-side, somewhat resembling the slats on a fence. There are six neurons embedded in this epithelium. Each neuron connects to the epithelium through branching nerve fibers projecting from the bottom of their cell bodies. A single nerve fiber projects from the top of each neuron and synapses with nerve fibers from the neurons above. These upper neurons are cross shaped, with one nerve fiber projecting from the bottom, top, right and left sides. The upper cells synapse with the epithelial nerve cells using the nerve tract projecting from the bottom of their cell body. The nerve tract projecting from the top continues the pathway, making a ninety degree turn to the right and continuing to the right border of the image. [Return to Figure 16.10].

Figure 16.11 image description: This diagram shows several types of nervous system cells associated with two multipolar neurons. Astrocytes are star shaped-cells with many dendrite like projections but no axon. They are connected with the multipolar neurons and other cells in the diagram through their dendrite like projections. Ependymal cells have a teardrop shaped cell body and a long tail that branches several times before connecting with astrocytes and the multipolar neuron. Microglial cells are small cells with rectangular bodies and many dendrite like projections stemming from their shorter sides. The projections are so extensive that they give the microglial cell a fuzzy appearance. The oligodendrocytes have circular cell bodies with four dendrite like projections. Each projection is connected to a segment of myelin sheath on the axons of the multipolar neurons. The oligodendrocytes are the same color as the myelin sheath segment and are adding layers to the sheath using their projections. [Return to Figure 16.11].

Figure 16.12 image description: This diagram shows a collection of PNS glial cells. The largest cell is a unipolar peripheral ganglionic neuron which has a common nerve tract projecting from the bottom of its cell body. The common nerve tract then splits into the axon, going off to the left, and the dendrite, going off to the right. The cell body of the neuron is covered with several satellite cells that are irregular, flattened, and take on the appearance of fried eggs. Schwann cells wrap around each myelin sheath segment on the axon, with their nucleus creating a small bump on each segment. [Return to Figure 16.12].

Attribution

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Nervous System” in Building a Medical Terminology Foundation by Kimberlee Carter and Marie Rutherford, licensed under CC BY 4.0. / A derivative of Betts et al., which can be accessed for free from Anatomy and Physiology (OpenStax). Adaptations: dividing Nervous System chapter content into sub-chapters.

-

↵

Check your answers: Nervous System Brain Anatomy labeling activity Diagram (Text Version)

This diagram shows the lateral view of the brain and the major lobes which are labeled. From the front of the brain (left): frontal lobe is responsible for thought processes and is part of the cerebrum, followed by a raised surface area known as precentral gyrus, a deep groove known as the central sulcus, and another raised area knowns as postcentral gyrus. The parietal lobe is responsible for processes senses such as the sense of touch, followed by the lateral sulcus which is another deep groove on the surface of the brain. The occipital lobe processes visual fields and the temporal lobe, which is responsible for memory capacity. The cerebellum is responsible for balance, followed by the brainstem which is often referred to as the medulla oblongata, and finally is the pons, which is known as the bridge connecting the cerebrum to the cerebellum. The parieto-occipital sulcus is a deep groove on the surface of the cerebrum.

includes the brain and spinal cord

all nervous tissue that is outside of the brain and spinal cord

region of the adult brain that is responsible for higher neurological functions such as memory, emotion, and consciousness

a collection of nucleic nerve tissue - has function in both the autonomic and endocrine systems - regulates homeostasis