6 Meat Colour

The post mortem colour development of meat varies greatly from one species to another, with variations in fresh beef being very prominent. Beef shows a range of colour from first being cut to the end of its shelf life (about three days).

Typical meat colour for different species is shown in Table 3.

| Species | Colour |

| Beef | Bright cherry red |

| Fish | Pure white to grey-white or pink to dark red |

| Horse | Dark red |

| Lamb and mutton | Light red to brick red |

| Pork | Greyish pink |

| Poultry | Grey-white to dull red |

| Veal | Brownish pink |

Table 3 Typical colour of meat from different species

Meat colour is significant to consumer acceptance of products. The bright red colour of good quality beef, sockeye salmon, and young lamb are naturally appealing, whereas the paler colours of veal and other fish species are less appealing to many (although more sought after by some ethnic groups). Dark meats such as horse are more popular in Quebec and European countries. Mutton (sheep over 12 months of age with darker flesh) appeals to an even smaller range of customers.

Factors Affecting Colour

Use of Muscles

Poultry provides a good opportunity to see and learn about the differences in meat colour. Meat cutters and cooks may often be asked why different parts of a chicken have white meat and other parts have dark meat, or why duck or game birds have mostly dark meat.

The colour of the meat is determined by how the muscle is used. Upland game birds, such as partridge and grouse, that fly only for short bursts have white breast meat. In contrast, ducks and geese and most other game birds that fly long distances have exclusively dark meat. In domestic poultry (chickens and turkeys), there is a difference between breasts (white meat) and thighs and drumsticks (dark meat).

Note: Chicken thighs, even when fully cooked, may have a reddish tinge and blood seepage from the thigh bone. This is normal; however, inexperienced customers may interpret this as a sign of not being cooked properly.

Proteins

Meat colour is associated with two proteins: myoglobin (in the muscle) and hemoglobin (in the blood). When animals are no longer alive and air comes in contact with the meat, myoglobin reacts with oxygen in an attempt to reach a state of equilibrium, at which point no further changes occur. As this process happens, the meat colour goes through three stages and three colours that are easy to see, especially on freshly cut beef meats.

- Purplish red (myoglobin): occurs immediately after a steak is sliced.

- Cherry red (oxymyoglobin): occurs several minutes after cutting and after exposure to oxygen.

- Brown (metmyoglobin): occurs when the iron in the myoglobin is oxidized, which usually takes about three days after cutting. (You may see steaks with this colour in the discount bin at a supermarket. The brown colour doesn’t mean there is anything wrong with the product; in fact, purchasing meat at this stage is a great way to stock up on cheaper steaks for the freezer.)

Oxygen

Oxygen plays two important roles, which affect the colour in opposite ways. As soon as meat is cut, oxygen reacts with the myoglobin and creates the bright red colour associated with oxymyoglobin. This will continue to develop until the iron in the myoglobin oxidizes to the point of the metmyoglobin stage.

Oxidation can also occur when iron in the meat binds with oxygen in the muscle. This can often occur during the processing of round steak from the hip primal and can be identified by the rainbow-like colours that appear from the reflection of light off the meat surface. The condition will remain after the product is cooked and can often be seen on sliced roast beef used in sandwich making. This condition does not alter the quality of the meat; however, it is generally less attractive to consumers.

Age

The pale muscles of veal carcasses indicate an immature animal, which has a lower myoglobin count than those of more mature animals. Young cattle are fed primarily milk products to keep their flesh light in colour. However once a calf is weaned and begins to eat grass, its flesh begins to darken. Intact males such as breeding bulls have muscle that contains more myoglobin than females (heifers) or steers (castrated males) at a comparable age.

Generally, beef and lamb have more myoglobin in their muscles than pork, veal, fish, and poultry. Game animals have muscles that are darker than those of domestic animals, in part due to the higher level of physical activity, and therefore they also have higher myoglobin.

Preventing Discolouration

Maintaining the temperature of fresh meat near the freezing point (0°C/32°F) helps maintain the bright red colour (bloom) of beef meats for much longer and prevents discolouration.

Meat should be allowed to bloom completely (the bloom usually reaches its peak about three or four days after cutting) or be wrapped on a meat tray with a permeable wrapping film as in supermarket meat displays. If portioned steaks are to be vacuum packed, doing so immediately after cutting (but before the bloom has started) will allow the steaks to bloom naturally when removed from the vacuum packaging.

Certain phases of meat processing can also trigger discolouration. Oxidation browning (metmyoglobin) can develop more rapidly than normal if something occurs to restrict the flow of oxygen once the bloom has started but has not been allowed to run its full course. The two most common examples are:

- Cut meat surfaces stay in contact too long with flat surfaces such as cutting tables, cutting boards, or trays.

- Meat is wrapped in paper (which means there is no further exposure to air and therefore no oxygen, which speeds up the browning effect).

The browning effect will occur naturally once the meat is exposed to oxygen.

There are two other types of discolouration that commonly occur with beef and pig meat. Although the cause of both types occurs before death (ante mortem), the actual change does not show up until after death (post mortem). The discolouration is a result of chemical reactions in the animal’s body due to stresses, known as pre-slaughter stress syndrome (PSS).

PSS can result in two different types of discolouration: PSE and DFD.

PSE (pale, soft, and exudative) occurs mainly in pigs (and in some cases has been found to be genetic). PSE is brought about by a sudden increase of lactic acid due to the depletion of glycogen before slaughter, which in turn causes a rapid decline in the pH post slaughter. The visible signs of PSE can be detected by the trained eye in the pork loin primal, where the flesh appears much paler than normal. The muscle meat is softer and may be very sloppy and wet to the touch and leaking meat juices, a result of a high proportion of free water in the tissues.

Although product with PSE is safe to eat, its shelf life is limited and it may become tougher sooner if overcooked. Products with PSE have limited use as fresh products but are used to manufacture cooked products such as formed ham and certain sausage varieties with a recommended limit of 10% (i.e., one part PSE to nine parts of regular meat), due to the high water content.

DFD (dark, firm, and dry) occurs mainly in beef carcasses but sometimes in lamb and turkey. In the meat industry, these carcasses are referred to as dark cutters. Unlike PSE meat, DFD meat shows little or no drop in the pH after slaughter. Instead, there may be an increase of stress hormones, such as adrenaline, released into the bloodstream. Consequently, glycogen (muscle sugar) is depleted before slaughter due to stresses. This decreases the lactic acid, which in turn affects the pH, causing it to not drop fast enough after slaughter. Therefore, the muscle meat, typically in the hip area of the carcass, may become very dry and dark.

Even after the carcass is aged and the meat has been processed and displayed, the dark appearance remains and bloom will not occur. In addition, the meat may also feel sticky to the touch, which limits shelf life. DFD meat is generally considered unattractive to the consumer; however, the meat remains edible and is still suitable for use in cooked products and sausage emulsions but should be limited to 10% (one part DFD to nine parts of regular meat).

Listed below are some causes of DFD that should be avoided:

- Transferring animals to strange surroundings (kill plant) and holding them for too long

- Treating animals roughly prior to and during transport (e.g., using cattle prods)

- Overcrowding cattle during shipping

- Mixing cattle with other animals they are not used to

- Preventing animals from having sufficient rest at the slaughterhouse prior to harvesting

- Dehydrating animals (not giving them enough water) prior to slaughter

- Causing over-excitement, pain, hunger, excessive noise, smell of blood

- Exposing animals to temperature extremes during transportation

- Shipping stress-susceptible animals, such as intact males (bulls), during severe weather

Note: DFD can occur anywhere between 12 and 48 hours prior to an animal’s slaughter.

Imperfections and Abnormalities in Meat

Even though meats arriving at their final destination (point of sale) have usually been approved and inspected, the product still requires further checks prior to sale and eating in case abnormal meat inconsistencies were missed in the inspection process. Some of these are caused by injuries or disease that occurred while the animal was alive, while others are naturally occurring parts of the animal’s body (glands in particular) that are removed prior to or during the cutting process.

Some examples are given here.

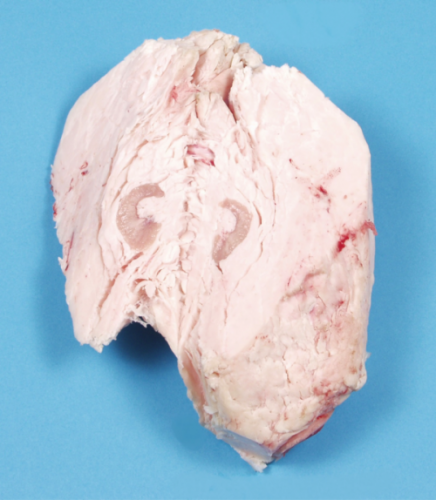

- Abscesses and cysts: infected or non-infected tumours from old injuries that are imbedded in muscles and sometimes close to bones (Figure 9).

- Blood spots and clots: usually from more recent injuries and also found imbedded in muscles or between muscle seams or on or near bone joints.

- Fibrous tissue: scar tissue, usually from very old injuries, with the appearance of white fatty seams or thin strands tightly bound together, making the muscle tough and unsightly.

- Lymph nodes and glands: lymph nodes are glands in the throat and back of the tongue that give a good indication of the general health of the animal; these are inspected on the animal carcass at the harvesting plant prior to being sold, but internal or intermuscular glands are not examined unless further inspection is recommended by a veterinarian. Consequently, three major glands are removed from beef, pork, and lamb during processing to ensure the public do not see them. They are the prescapular gland, located in the neck and blade sub-primals below the junction of the fifth cervical vertebra (Figure 10); the prefemoral gland, located at 90 degrees to the round bone on the hip on the exterior of the sirloin tip imbedded in the cod fat pocket (Figure 11); and the popliteal gland, located in the outside round sub-primal in the hip primal between the eye of the round and the outside round flat under the heel of round, imbedded in a fat pocket (Figure 12).