Chapter 1 – The Role of Logistics in Supply Chains

1.1 Introduction

A supply chain is a network that creates products and services and delivers those products and services to customers. Supply chains include marketing, sales, financing, procurement, processing operations, maintenance, service, and logistics. The focus of this Open Educational Resources (OER) digital textbook is logistics. Logistics refers to the processes and networks used to move and store materials within supply chains and move products to their final destination. Logistics is considered a subset or part of a supply chain.

The coffee sitting on your desk and the food in your home arrived via a product supply chain. The computer you are using to access the information in this OER came via a product supply chain. The digital information you are reading (in the form of electrons and signals) is available for use thanks to an information supply chain. A haircut appointment or a lawyer’s appointment are examples of activities that provide services to you as part of a service supply chain. In this chapter, we will explore the role of logistics in supply chains.

Figure 1.1

Coffee Cup on Desk

Note: From Scott, 2021. CC BY 2.0

1.2 Chapter Learning Objectives

- Explain the role of logistics in supply chains.

- List the factors considered when designing the logistics in a supply chain.

- Explain the elements that make up a logistics network.

- Examine the importance of logistics to the economy.

- Review supply chain professional organizations and associations.

1.3 Pre-Assessment

1.4 The Role of Logistics in Varying Types of Supply Chains

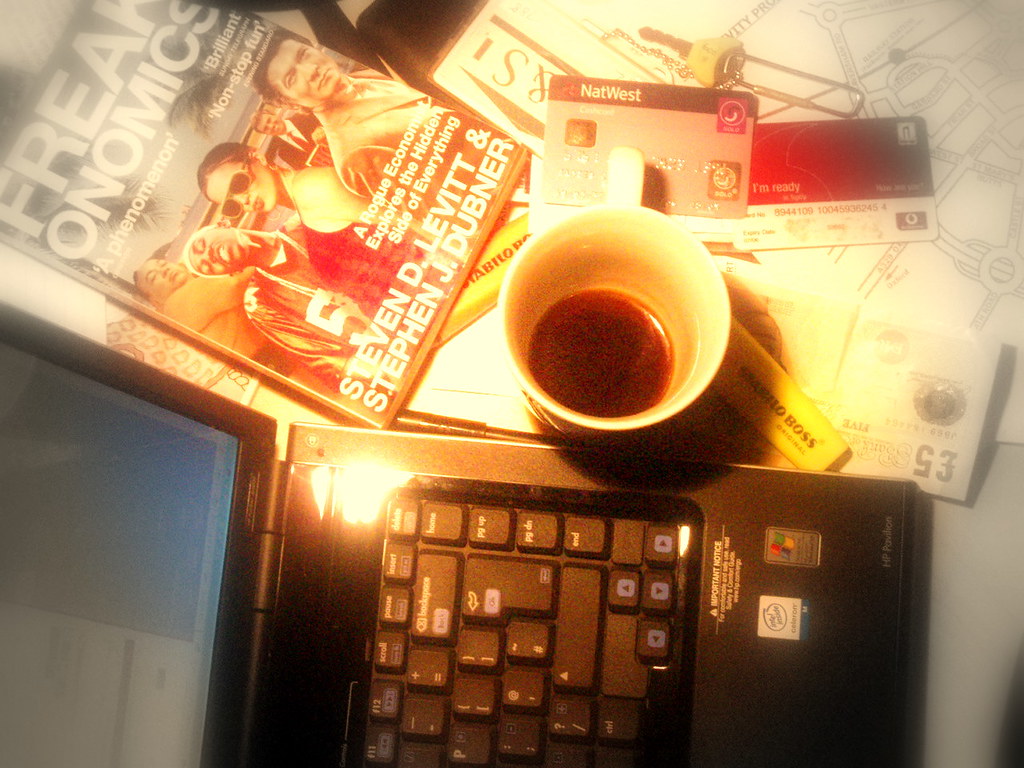

Product Supply Chains

Product supply chains start with the demand from a customer for a product. Products begin in the form of raw materials that must be sourced, gathered, converted, and manufactured into the required products. Then, the product is transported to end-users. Products will often stop at warehouses as they move through the product supply chain. There are many steps to convert and transform raw materials into final products that will be delivered to a consumer. Logistics supports the transportation steps in supply chains. Logistics can be categorized as :

- Internal logistics

- The logistics of moving materials, parts, and products inside a facility or single location

- External Logistics

- The logistics of moving materials, parts, and products between multiple locations, such as:

- suppliers

- factories

- distributions centres

- receiving/ shipping docks (inbound and outbound logistics)

- customers

- The logistics of moving materials, parts, and products between multiple locations, such as:

Figure 1.2

Note. From co-author, 2021. [Image Description]

Information Supply Chain

The information generated by each process in a supply chain supports the supply chain’s logistics networks and operations. This information is itself a supply chain. Consider that similar to products, information is comprised of raw materials such as data and artifacts, that are processed into information such as knowledge, documents like bills of lading, certificates such as health and safety certificates, approvals, and reports. Logistical activity is required to move that information and then store it. In contrast to the physical movement of products, information is moved or transmitted through information systems and electronic data interchange (EDI). Information can be found in reports that need to be distributed in hardcopy, digital, and electronic formats. Storage then takes place in databases, servers, and data warehouses.

Service Supply Chain

Services like haircuts, accounting services or legal advice also have a supply chain. Services unlike products are typically intangible and require supply chain processes that acquire products, knowledge, and develop talent that will be used in the provision of services to customers. Logistics for services depends on producing and supplying products like scissors for barbers, computers for accountants, and cyber-secure information systems to ensure confidentiality of electronic documents for paralegal services.

Reverse Supply Chain

Whilst downstream logistics refers to the forward movement of raw materials through multiple steps of production, storage, and transportation of final products, upstream logistics refers to the reverse direction movement of products from the customer back through one or more steps of the forward logistics process.

Reverse Supply Chains, therefore, refer to the backward flow of products from downstream to upstream in a supply chain. This process may occur if an item is returned to the manufacturer due to damage, for example, reverse logistics would move these products back to their point of origin or another destination, such as a repair center, upstream in the process.

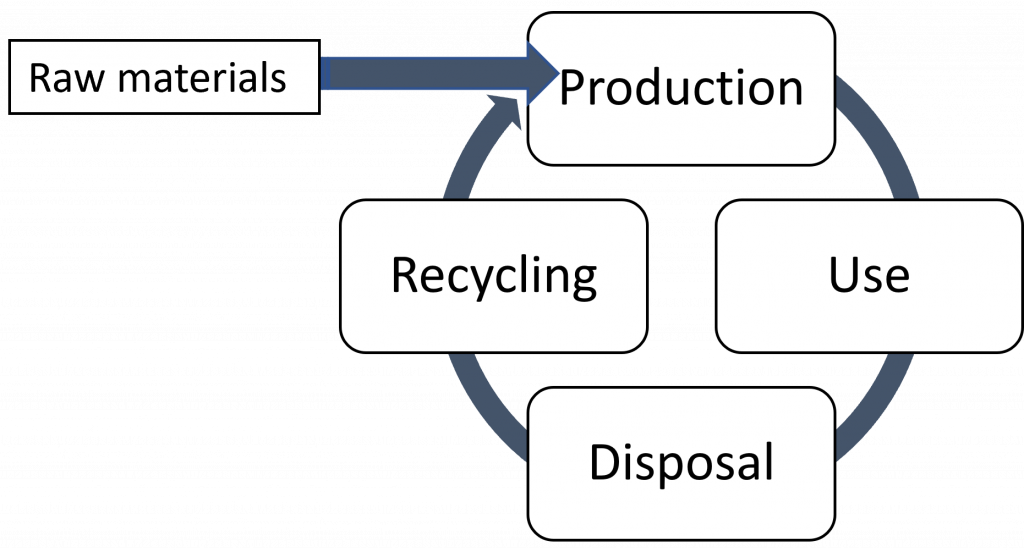

Circular Supply Chain

Circular Supply Chains are a development from the traditional linear product supply chain. They start with raw materials, convert them to products, and then back to the raw materials from whence they started. These types of supply chains emphasize reusing waste materials and returned or old products. Sustainability, social, and economic responsibility are integral to circular supply chains.

Logistics in supply chains considers the total system cost in planning and managing the transportation and storage of products. Starting from the extraction point of the raw materials back to the re-entry of these same raw materials after their initial product life has expired, back into the beginning of a new supply chain in the next life cycle they will experience.

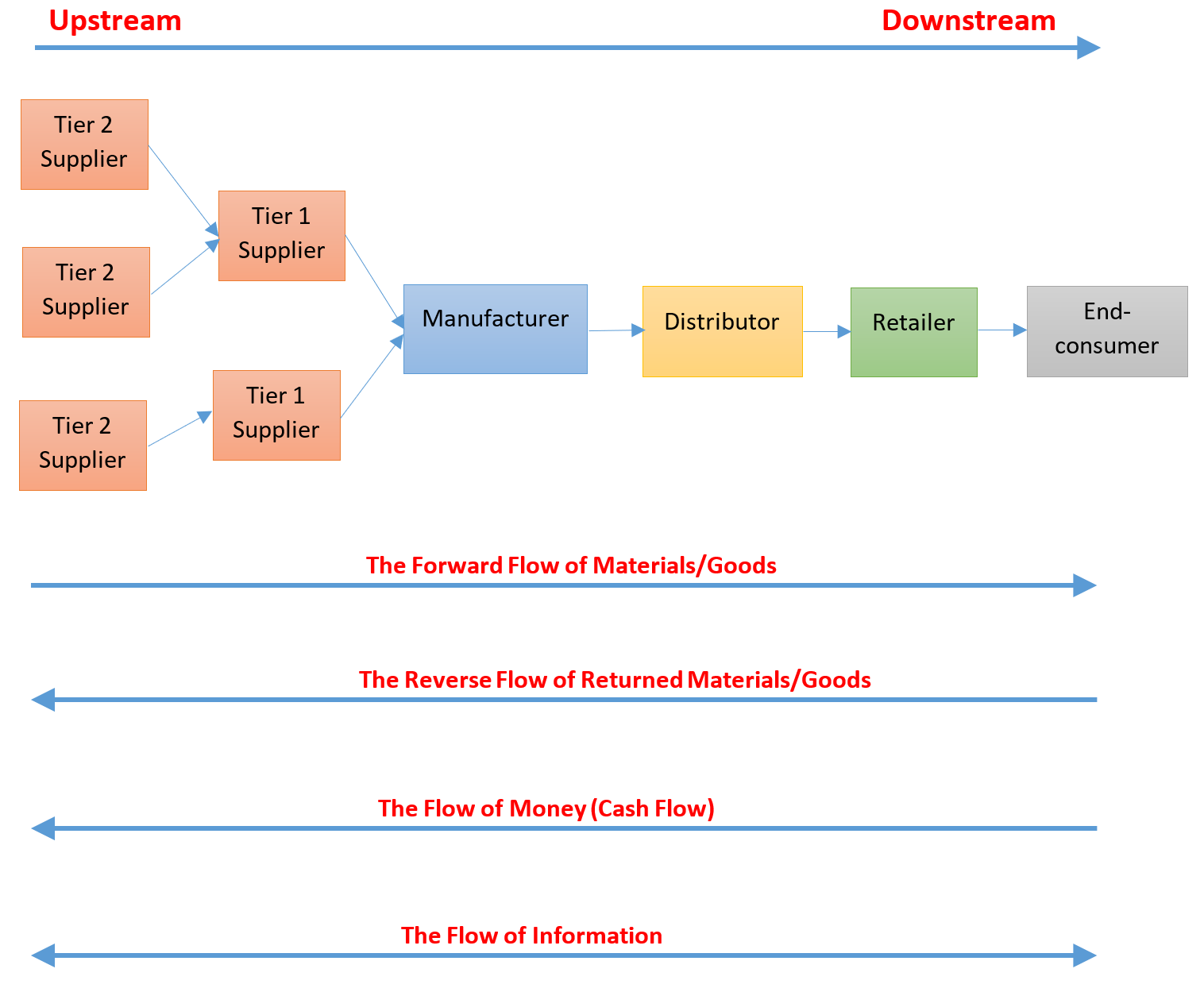

Flow in Supply Chains

Figure 1.3 shows a simple linear supply chain. In the supply chain, Tier 2 represents raw materials suppliers. Tier 1 represents the sub-assembly parts made from those raw materials. They are then manufactured into products and distributed to retailers where customers, the end-consumer or user, acquire them. This progression represents the forward flow of materials/goods. Other “flows” include the flow of information that runs up and downstream, the flow of money which runs from downstream to upstream, and the reverse flow of materials when a product is returned to the manufacturer (for example, if a product is damaged). Logistics, represented by the blue arrows that connect each tier and each step in the supply chain, are required to manage all of the flows and movement in a supply chain.

Figure 1.3

Upstream and Downstream of a Supply Chain and its Flows

Note: From Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 [Figure Description]

1.5 Variations for Consideration when Designing Logistics in Supply Chains

The following is a list of common variations to a linear supply chain:

- There can be many sub-tiers in a supply chain.

- Many different modes of transport and steps may be used to move products from a distribution center to a customer. For example, a large truck may handoff to a smaller vehicle with a driver to walk to the final delivery point. A person might even then wrap the product as a gift and send it back into the logistics network for yet another journey to a new final destination (gift recipient).

- There might be fewer steps than this in a local, self-sufficient environment.

- The online shopping world can see products bypass some of these steps.

- There is a reverse flow from downstream to upstream for products returned to the manufacturer or an alternate destination for refund, scrap, repair, rework or upgrade.

- The terms supply chain and value chain have slightly different meanings, but for this OER, they will be considered to mean the same thing.

- Supply chains for information flow move:

- back and forth (upstream and downstream)

- manual (paper) and digital forms

- synchronously and asynchronously

- with established protocols and security in place for accessing data and information

- Information is generated from data collected throughout the supply chain.

- Data integrity, timeliness, and accuracy are vital to this information.

Example: A Bottle of Water Moves Through A Supply Chain

This video demonstrates a product supply chain for bottled water. The logistics component of this supply chain is made up of the trucks that transport the bottled water and the forklifts that load and unload the inventory. Consider the cost of a bottle of water, typically $1.50 or $2.00. How much of that cost goes toward the water, processing, packaging, and the cost of logistics that is spent moving and storing the bottle of water?

W.P. Carey School of Business. (2010, April 6). Module 1: What is supply chain management? (ASU-WPC-SCM) – ASU’s W. P. Carey School [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Mi1QBxVjZAw

1.6 Supply Chain Management

Supply Chain Management is often abbreviated as SCM. Supply chain management is the management of goods and services from the initial idea to the end-users and back to their origin. Supply Chain Management includes procurement (or purchasing) demand planning, sales and operations planning (S&OP), execution and management of supply chain activities, strategic sourcing, transportation management, warehouse management and inventory management. According to APICS Dictionary, 13th edition, it involves the design, planning, execution, control, and monitoring of all supply chain activities. SCM includes:

- Demand planning

- Purchasing

- Sales and Operations Planning

- Operations / execution

- Distribution

1.7 Managing Elements in Logistic Networks

This video offers definitions and explains the role of managing logistics in a supply chain.

Aims Education, UK. (2016, July 21). What is logistics management? Definition & importance in supply chain [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/4-QU7WiVxh8

External Logistics

Materials and products also need to be moved and stored when they are inside a manufacturer’s facility, inside a distribution centre and when you bring them home. This OER will focus on the logistics between Suppliers and Manufacturers, between Manufacturers and Distribution Centres, between Distribution Centres and Retail stores and between Distribution Centres and Customers, in other words, before and after the manufacturing/assembly process.

Forward Logistics

Logistics occur at every step and help the product move through the supply chain from origin to end-user. This is known as Forward Logistics which means product moving forward or downstream from the point of origin (e.g. supplier, manufacturer) to point of consumption (e.g. end-user, customer), or expressed differently, from raw materials to the final product destination. Forward logistics can take place between:

- Suppliers and Manufacturers

- Manufacturers and Distribution Centres

- Distribution Centres and Retail stores

- Distribution Centres and Customers

Reverse Logistics

Product moving backward or upstream from the customer back to the supplier or manufacturer is called reverse logistics.

Reasons for using reverse logistics:

- The defective product needs to be returned for replacement or repair.

- The product needs servicing.

- The product needs to be disposed of or scrapped.

- The product is returned for upgrading or refurbishment.

- The product is repurposed.

Figure 1.4

Nespresso Expands Aluminum Recycling and Reuse

Note. From Nestlé, 2008. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Further Reading: Reverse Logistics Examples

“Reverse logistics has been a part of retailing for over 100 years when retailers like Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward began delivering goods by railroad. In the past few years, e-commerce has led to an explosion of reverse logistics — or, shipping goods from the consumer back to the retailer. Consumers have come to expect no-fuss return policies; that’s why returns on e-commerce orders are three to four times higher than brick and mortar purchases, according to the Reverse Logistics Association. That means reverse logistics is a fact of life for most companies.” (Syverson, 2021, paras. 1-2).

“Reverse logistics are a very important part of a circular supply chain that finds new uses and/or ensures proper disposal of products that are at the end of their life cycle. Recycling bottles, plastics, batteries and other materials are part of the reverse supply chain.” (Guest Blogger, 2017). Reverse Logistics 101 discusses several successful examples of manufacturers like Apple, H&M, and Dasani using reverse logistics in their processes.

1.8 The Role of Logistics in Inventory in the Supply Chain

Managing inventory is one of the most important activities in a supply chain. Materials/goods are needed to provide manufacturers with the exact items they need, in the right order, the right quality delivered to the right location, and at the right time. Without all of this happening, it will be impossible to produce high-quality goods and meet commitments to our customers. In addition, when goods are ready for shipment, the outbound supply chain needs to be organized in such a way that customers receive their requested orders in a cost-efficient manner.” (Faramarzi & Drane, n.d., Chapter 7)

Types of Inventory in the Supply Chain

- Finished goods: These are goods or products that are ready to be shipped to a customer.

- Raw materials: These are materials used at the beginning of the manufacturing process. These are the composite materials used to make materials or products—for example, commodities and substances like iron ore which will eventually be used to make steel.

- Purchased components: These are parts that have had some processing done to them or some level of assembly into more complex products

- Operating supplies: These are materials and products used to support manufacturing, such as stationary, oils, gaskets, and water.

- Work-in-process: These products have had some processing done to them and are at a stage between raw materials and finished goods in the manufacturing process.

This section was adapted from Chapter 7: Supply Chain Management from Introduction to Operations Management by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane, Seneca College, licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Reasons for Holding Inventory

Many reasons exist for keeping stocks of inventory. Some of the most common include:

- Seasonal demand

- An example is a chocolate manufacturer that does not have the capacity to produce all the needed product for Christmas. They may begin building inventory in late spring to have enough on hand for orders in November and December.

- Risk

- A manufacturer may carry large amounts of inventory if they have some uncertainty or risk in their supply base. If suppliers have some risk of shortages, work stoppages, poor quality, or late deliveries, then more stock may be carried.

- Discounts

- Firms may be tempted by extra discounts often provided by purchasing large order sizes. Perhaps they may want to minimize transportation costs. There may also be some worry about future price increases that can cause organizations to build up their inventories.

- Anticipated demand

- Retailers carry inventory to ensure that they do not run out of what they anticipate their customers may want. Distributors and retailers may try to balance the cost of keeping extensive inventories on hand and providing excellent customer service with few disappointed customers. However, it is often a challenge to anticipate exact customer behaviour.

- Scheduling logistics

- It is challenging to synchronize the incoming flow of materials and goods to meet production schedules and ship to customers as promised. As a result, inventory may be stored at many locations along the supply chain. This extra storage causes extra costs and inefficiencies for each organization. (Faramarzi & Drane, n.d., Chapter 7)

Inventory that is moved and stored in the logistics network can be of any of the types listed above. The cost of inventory and logistics increases as you move downstream through the supply chain. Finished goods are more expensive than other types of inventory because they acquire value through the manufacturing process and the supply chain.

This section was adapted from Chapter 7: Supply Chain Management from Introduction to Operations Management by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane, Seneca College, licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

After Logistics

Is there an end to logistics? Is the life cycle of a product linear or straightforward; a product starts with an idea or a need, then is finished when the product is no longer needed or can no longer perform its intended purpose? So what happens to the product at this point? It might just sit around. Do you have a drawer full of old electronics products?

Figure 1.7 shows a drawer open with an old hard drive, a Blackberry, an iPhone 3, and various memory storage devices. In a linear economy, they would just be thrown out into landfills. Could obsolete products be repurposed? I re-purposed my old iPhone 3 as an iPod that I hooked up to my stereo to listen to saved songs and streamed content from the internet for a long time.

Figure 1.5

Obsolete Electronics in a Drawer

Note. From co-author, 2021

In a circular economy, obsolete products such as those shown in Figure 1.7 might be repurposed, reused, or recycled for parts. They might be broken down into their sub-components or raw materials so they can re-enter the supply chain in a new form. In a circular economy, the initial design of products, supply chain, and logistics need to be planned and managed differently. They need to take into account reverse logistics for the successful continuation of the product’s life cycle.

1.9 The Importance of Logistics and the Economy

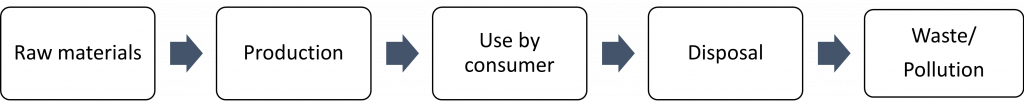

Moving from a Linear to a Circular Economy

A good question to consider is what happens to materials and products on a supply chain after consumers are done with them? Look around you and ask yourself what will happen to your clothes, products you are using, or the leftovers from services with which you engage? There are many ways to make products and services. There are a wide variety of materials and processes used to make them. Products and services are made using energy from many different sources – both renewable and from sources that produce much pollution.

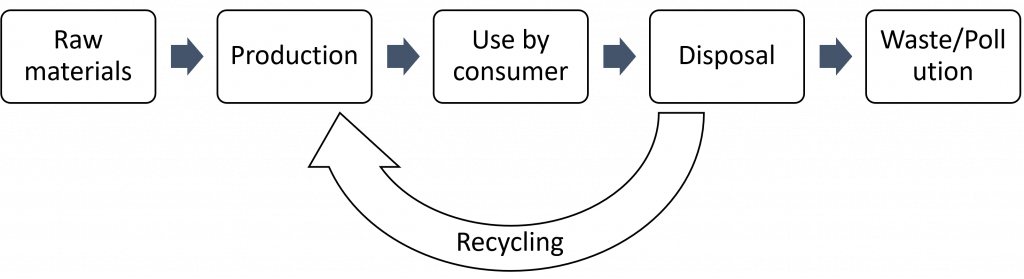

This image shows a linear economy with a straight line from raw materials to landfills; a reuse economy showing new use of materials, and a circular economy cycle that re-uses materials.

Linear, Reuse, and Circular Economies

Note. From co-author, 2021 [Image Description]

Linear Economy

A linear economy, shown at the top of Figure 1.8, follows a traditional “take-make-dispose” plan. This type of economy involves collecting raw materials and transforming them into products that will be used until they are discarded as waste. In the linear economic system, value is created by producing and selling as many products as possible.

The linear economy often ignores the costs of waste generated during manufacturing and costs incurred after the useful product life has ended. The total system costs, including processing, disposal, and logistics (handling and storage) are considered.

Further Reading: The Narwhal

An example of linear supply chains and unaccounted for costs of disposal and cleanup are discussed in an article in The Narwhal about Canada’s oilsands and old oil wells:

“Ottawa is paying to clean up Alberta’s inactive wells. Are the oilsands next? As $1 billion in federal funds go to clean up inactive wells, experts are sounding alarm bells about the ‘super experimental’ realm of tailings ponds reclamation and what could be more than $100 billion in unfunded liabilities in the oilsands” (Riley, 2020, para. 1).

Reuse or Recycling Economy

A reuse or recycling economy, shown in the middle of Figure 1.8, includes collecting raw materials and transforming them into products. It is similar to a linear economy model. However, unlike the linear economic model, some of those product materials can be put back into the value stream and reused to manufacture new products or distribute more products. In contrast, other products are disposed of as waste. The design, planning, and managing of logistics must consider the recycling process steps, transportation modes, storage, and costs in this type of economy.

Further Reading: Ontario’s Blue Box Program

An example of this is the Blue Box program for collecting recyclable materials in Ontario, Canada. This article by Stewardship Ontario discusses how costs for processing recycled materials are going up, yet revenues from them are decreasing.

Circular Economy

The circular economy, shown at the bottom of Figure 1.8, is an alternative to Canada’s dominant linear economic model. It is grounded in the study of living systems and nature itself. We are pretty used to collecting and transforming resources that are later consumed and become waste once their lifespan ends.

If you look at nature, you can see that processes are different. A tree is born from a seed, it grows and reproduces, and when it dies, it goes back to the soil, enriching it and providing nourishment for new life. How could we apply that process to the objects we use at home and work?

The circular economy looks at all the options across the supply chain to use as few resources as possible. It seeks to keep resources in circulation for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them while in use, and recover and regenerate products at the end of their service life. The circular economy tries not to view garbage as waste but as a potential resource to be reused. This new way of understanding goods also means designing products using materials that can be easily dismantled and recycled when their initial life cycle is done.

In a circular economy, one considers the impact of materials, resources, and energy used to make products, move them and store them. The goal is to maintain their value for as long as possible, including returning them back into the manufacturing cycle.

Further Reading: Government of Ontario Supply Chain Rules

The Government of Ontario is changing supply chain rules by shifting responsibility for recycling products at their end of life to their producers. This change will impact where costs are assigned in the logistics networks: “the price of packaged goods expected to go up as costs of recycling shift entirely to producers” (Dunn, 2020, para. 1).

1.10 Supply Chain Professional/Industry Organizations

The following organizations are led by experts and interested members who work in supply chains. They conduct research, share knowledge, advocate, train, and provide platforms for learning and discussing what is happening in the industry. They often have student chapters.

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP)

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) is an organization based in the United States that helps people working in the supply chain field connect, network, understand and develop supply chain networks. Professional organizations like this have current and relevant information about supply chains and logistics within supply chains.

CSCMP defines logistics management as “that part of supply chain management that plans, implements, and controls the efficient, effective forward and reverses flow and storage of goods, services and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption in order to meet customers’ requirements.” (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, n.d., para. 5).

CSCMP further defines the boundaries and relationships that logistics management has in relation to the rest of the supply chain:

“Logistics management activities typically include inbound and outbound transportation management, fleet management, warehousing, materials handling, order fulfillment, logistics network design, inventory management, supply/demand planning, and management of third-party logistics services providers. To varying degrees, the logistics function also includes sourcing and procurement, production planning and scheduling, packaging and assembly, and customer service. It is involved in all levels of planning and execution–strategic, operational, and tactical. Logistics management is an integrating function, which coordinates and optimizes all logistics activities, as well as integrates logistics activities with other functions including marketing, sales manufacturing, finance, and information technology.” (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, n.d., para. 7).

Supply Chain Canada (SCC)

Supply Chain Canada (SCC) is a Canadian organization that is similar to CSCMP. SCC’s vision is “to ensure Canadian supply chain professionals and organizations are recognized for leading innovation, global competitiveness, and driving economic growth” (Supply Chain Canada, 2021, para. 1). Its mission is to “provide leadership to the Canadian supply chain community, provide value to all members, and advance the profession” (Supply Chain Canada, 2021, para. 2).

The Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM)

The Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM) is “the global leader in supply chain organizational transformation, innovation, and leadership. As the largest non-profit association for supply chains, ASCM is an unbiased partner, connecting companies around the world to the newest thought leadership on all aspects of the supply chain.” (6). ASCM has many resources for supply chain professionals. ASCM has certificate training programs on supply chain subjects, including a Warehousing Certification program.

Joining and participating in activities with professional organizations like these are valuable for networking, learning, and staying current with the activities and practices in supply chains.

1.11 Post Assessment (Check Your Understanding)

1.13 A Message From the Co-author

“While in Tokyo, Japan, I noticed that there were two sizes for cans of Coca-Cola in a vending machine – 10 fluid oz. (approx. 296 ml) and 12 fluid oz. (approx. 355 ml). However, both were the same price. I asked a Japanese friend why this was the case. Wouldn’t everyone just pick the bigger one, as I did, for the same price? He said that he usually bought the 10 oz. can because that was all he wanted to drink. He did not need the other two oz., so why buy it and waste it? The message is that the Coca-Cola supply chain satisfied the demand for two different customers, but the cost of the extra 2 oz. of Coke was insignificant to the cost of the logistics of supplying the product, leading to the same end cost.” (Co-author, 2021)

1.14 Summary

In this chapter, we have explained the role of logistics in supply chains. Logistics supports the transportation of raw materials and products between locations or facilities as they move along the supply chain ending their initial life with the consumer. The circular economy follows a product through its next phases where it is discarded or moves back into the supply chain. We have considered elements such as defective products and inventory that make up a logistics network, examined the importance of logistics to the economy, and provided a review of a supply chain professional organizations and associations.

1.15 Chapter References

Association for Supply Chain Management. (2021). Contact us. ASCM. https://www.ascm.org/contact-ascm/

Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. (2021). CSCMP supply chain management definitions and glossary. CSCMP. https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Academia/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921

Dunn, T. (202, October 20). Ontario’s new blue box plan will recycle more, but it’ll cost you more as well, experts say. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-s-new-blue-box-plan-will-recycle-more-but-it-ll-cost-you-more-as-well-experts-say-1.5768577

Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. (n.d.) Introduction to operations management. Seneca College Pressbooks Network. https://pressbooks.senecacollege.ca/operationsmanagementintro/. Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. (n.d.) Upstream and downstream of a supply chain and its flow [Image]. Seneca College Pressbooks Network. https://pressbooks.senecacollege.ca/operationsmanagementintro/chapter/supply-chain/ Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Guest Blogger. (2017, July 10). Reverse logistics 101. All Things Supply Chain. https://www.allthingssupplychain.com/reverse-logistics-101/

Nestlé. (2008, May 8). Nespresso expands aluminum recycling and reuse [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nestle/16354467964. Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Riley, S.J. (2020, June 5) Ottawa is paying to clean up Alberta’s inactive wells. Are the oilsands next? The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/ottawa-paying-clean-up-albertas-inactive-wells-oilsands-next/

Scott, C. (Photographer). (2006, September 8). Coffee cup on desk [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/callumscott2/265229417/in/photolist-prnsZ. Licensed for reuse CC BY-NC 2.0

Supply Chain Canada. (2021). Who we are. SSC. https://www.supplychaincanada.com/about/who-we-are

Syverson, S. (2021, October 7). 45 Things you should know about reverse logistics. Warehouse Anywhere. https://www.warehouseanywhere.com/resources/45-things-about-reverse-logistics/

1.16 Image Descriptions

Figure 1.2 This figure shows a generic product supply chain flowchart: Raw materials selection then logistics (movement and storage, warehouses and bulk storage), then manufacture stage, then logistics (movement and storage, distribution centres and warehouses), to retail stores and/or consumers, then to product end use. [Back to Image]

Figure 1.3: This figure illustrates the upstream and downstream of a supply chain and its flows. In this chain, Tier 2 represents raw materials suppliers. Tier 1 represents the parts of the product made from those raw materials. They are then manufactured into products and distributed to retailers where customers, the end-consumer or users acquire them. This progression represents the forward flow of materials and/or goods indicated in Figure 1.3. Other “flows” include the flow of information that runs up and downstream, the flow of money which runs from downstream to upstream, and the reverse flow of materials when a product is returned to the manufacturer (E.g., if a product is damaged). Logistics, represented by the blue arrows that connect each tier and each step in the supply chain are required to manage all flows and movement in a supply chain. [Back to Image]

Figure 1.6: The first figure shows a linear economy following a traditional “take make- dispose” plan. Starting from the left to the right, there are Raw materials; Production; Use by the consumer; Disposable; Waste Pollution. This type of economy involves collecting raw materials and making them into products that will be used until they are discarded as waste. The second figure is reuse Economy is a reuse or recycling economy which includes collecting raw materials and transforming them into products. This economy is like a linear economy, the only difference is that some materials can be put back into the value stream and reused to manufacture new products or distribute more products.The third figure is Circular Economy which shows an alternative to Canada’s dominant linear economic model. From raw materials; Production; Use; Disposable to recycling. The circular economy looks at all options across the supply chain to use as few resources as possible and tries not to view garbage as waste but instead as a potential resource to be reused. [Back to Image]