Chapter 5: Evaluating Sources

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Critically evaluate the sources of the information you have found.

- Evaluate the content of selected material for your purposes.

5.1 Overview of evaluation of sources

Searching for information is often nonlinear and iterative, requiring the evaluation of a range of information sources and the mental flexibility to pursue alternate avenues as new understanding develops. (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2016).

You developed a viable research question, compiled a list of subject headings and keywords and spent a great deal of time searching the literature of your discipline or topic for sources. It’s now time to evaluate all of the information you found. Not only do you want to be sure of the source and the quality of the information, but you also want to determine whether each item is appropriate fit for your own review. This is also the point at which you make sure that you have searched out publications for all areas of your research question and go back into the literature for another search, if necessary.

In general, when we discuss evaluation of sources we are talking about looking at quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation, currency, and credibility factors in a specific work, whether it’s a book, ebook, article, website, or blog posting. Before you include a source in your literature review, you should clearly understand what it is and why you are including it. According to Bennard et al., (2014), “Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work.” (para. 4).

When evaluating a work for inclusion in, or exclusion from, your literature review, ask yourself a series of questions about each source.

5.1.1 Evaluating books

For primary and secondary sources you located in your search, use the ASAP mnemonic to evaluate inclusion in your literature review:

5.1.1.1 Age

Is it outdated? The answer to this question depends on your topic. If you are comparing historical classroom management techniques, something from 1965 might be appropriate. In Nursing, unless you are doing a historical comparison, a textbook from 5 years ago might be too dated for your needs.

A General Rule of Thumb:

5 years, maximum: medicine, health, education, technology, science

10-20 years: history, literature, art

5.1.1.2 Sources

Check reference or bibliography sources as well as those listed in footnotes or endnotes. Skim the list to see what kinds of sources the author used. When were the sources published? If the author is primarily citing works from 10 or 15 years ago, the book may not be what you need.

5.1.1.3 Author

Does the author have the credentials to write on the topic? Does the author have an academic degree or research grant funding? What else has the author published on the topic?

5.1.1.4 Publisher

Look for academic presses, including university presses. Books published under popular press imprints (such as Random House or Macmillan, in the U.S.) will not present scholarly research in the same way as Sage, Oxford, Harvard, or the University of Washington Press.

Other questions to ask about the book you may want to include in your literature review:

- What is the book’s purpose? Why was it written? Who is the intended audience?

- What is the conclusion or argument? How well is the main argument or conclusion supported?

- Is it relevant to your research? How is it related to your research question?

- Do you see any evidence of bias or unsubstantiated data?

5.1.2 Evaluating websites

In your research, it is likely you will discover information on the web that you will want to include in your literature review. For example, if your review is related to the current policy issues in public education in the United States, a potentially relevant information source may be a document located on the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) website titled The Condition of Education 2017. Likewise, for nursing, an article titled Discussing Vaccination with Concerned Patients: An Evidence-Based Resource for Healthcare Providers is available through the nursingcenter.com website. How do you evaluate these resources, and others like them?

Use the RADAR mnemonic (Mandalios, 2013) to evaluate internet sources:

5.1.2.1 Relevance

How did you find the website and how is it relevant to your topic?

- Was it recommended by a reliable source?

- Was it cited in a scholarly source, such as a peer-reviewed journal?

- Was it linked from a reputable site?

5.1.2.2 Authority

Look for the About page to find information about the purpose of the website . You may make a determination of its credibility based on what you find there. Does the page exhibit a particular point of view or bias? For example, a heart association or charter school may be promoting a particular perspective – how might that impact the objectivity of the information located on their site? Is there advertising or is there a product information attached to the content?

5.1.2.3 Date

- When was the page created?

- Is it kept up to date?

- Are the links current and functional?

5.1.2.4 Appearance

- Does the information presented appear to be factual?

- Is the language formal or academic?

- How does it compare to other information you have read on the topic?

- Are references or links to cited material included?

5.1.2.5 Reason

What is the web address or URL? This can give you a clue about the purpose of the website, which may be to debate, advocate, advertise or sell, campaign, or present information. Here are some common domains and their origins:

- .org – An advocacy website for an organization

- .com – A private or commercial site

- .net – A network organization or Internet provider/no longer frequently used

- .edu – The site of a higher educational institution

- .gov – A federal government site

- .wa.us – A state government site which may include public schools and community colleges

- .uk, .ca, .jm – A country site

Mike Caulfield (2017), the author of Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, recommends a few simple strategies to evaluate a website (as well as social media):

- Check for previous work: Look around to see if someone else has already provided a synthesis of the research described.

- Go upstream to the source: Go “upstream” to the source of the claim. Most web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the credibility and reliability of the information.

- Read laterally: Read laterally. Once you get to the source of a claim, read what other people say about the source (publication, author, etc.). The truth is in the network.

5.1.3 Evaluating journal articles

It is likely that most of the resources you locate for your review will be from the scholarly literature of your discipline or in your topic area. As we have already seen, peer-reviewed articles are written by and for experts in a field. They generally describe formal research studies or experiments with the purpose of providing insight on a topic. You may have located these articles through Google, Google Scholar, a subscription or open access database, or citation searching. You now may want to know how to evaluate the usefulness for your research. As with the other resources, you are again looking for authority, accuracy, reliability, relevance, currency, and scope. Looking at each article as a separate and unique artifact, consider these elements in your evaluation:

5.1.3.1 Credibility/Authority

ASK: Who is the author? Is this person considered an expert in their field?

- Search the author’s name in a general web search engine like Google.

- What are the researcher’s academic credentials?

- What else has this author written? Search by author in the databases and see how much they have published on any given subject.

- How often or frequently has this article been cited by other scholars?

Citation analysis is the study of the impact and assumed quality of an article, an author, or an institution, based on the number of times works and/or authors have been cited by others. Google Scholar is a good way to get at this information.

5.1.3.2 Accuracy

Check the facts. ASK:

- Can statistics be verified through other sources?

- Does this information seem to fit with what you have read in other sources?

5.1.3.3 Reliability/Objectivity

ASK: Is there an obvious bias? That doesn’t mean that you can’t use the information, it just means you need to take the bias into account.

- Is a particular point of view or bias immediately obvious, or does it seem objective at first glance?

- What point of view does the author represent? Are they clear about their point of view?

- Is the article an editorial that is trying to argue a position?

- Is the article in a publication with a particular editorial position?

5.1.3.4 Relevance

ASK: The hard questions:

- Is the information relevant to your topic/thesis?

- How does the article fit into the scope of the literature on this topic?

- Who is the intended audience for this source?

- Is the material too technical or too clinical?

- Is it too elementary or basic?

- Does the information support your thesis or help you answer your question, or is it a challenge to make some kind of connection?

- Does the information present an opposite point of view so you can show that you have addressed all sides of the argument in your paper?

5.1.3.5 Currency

ASK:

- When was the source published?

- How important is current information to your topic, discipline, or paper type?

- Does older material add to the history of the research? Or do you need something more current to support your thesis?

5.1.3.6 Scope and Purpose

To determine and evaluate in this category, ASK:

- Is it a general work that provides an overview of the topic or is it specifically focused on only one aspect of your topic?

- Does the breadth of the work match your expectations?

- Is the article meant to inform, explain, persuade or sell something. Be aware of the purpose as you read the content and take that into consideration when deciding whether to use it or not.

For Nursing and other medical articles ASK:

- What are the research methods used in the article?

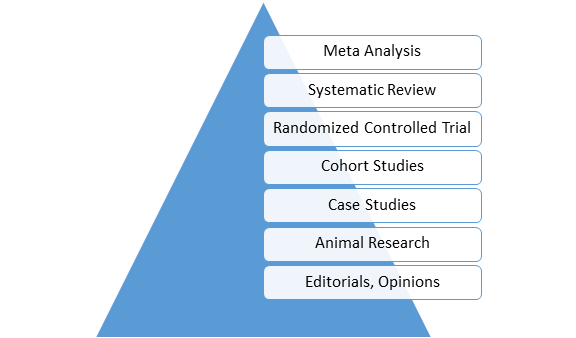

- Where does the method fall in the evidence pyramid? Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are the most credible, with articles that are opinions the least credible.

- Meta Analysis: A systematic review that uses quantitative methods to summarize the results.

- Systematic Review: An article in which the authors have systematically searched for, appraised, and summarized all of the medical literature on a specific topic.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): RCTs include a randomized group of patients in an experimental group, as well as a control group. These groups are monitored for the variables/outcomes of interest.

- Cohort Study: Research identifies two groups (cohorts) of patients, one which did receive the exposure of interest, and one which did not, and follows these cohorts for a specified duration of time, in order to measure the outcome of interest.

- Case Study: Involves identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and control patients without the same outcome, and looks to see if they had the exposure of interest.

- Animal Research / Lab Studies: Information creation begins at the bottom of the pyramid: This is where ideas and laboratory research take place. Ideas turn into therapies and diagnostic tools, which are then tested with lab models and animals.

- Background Information / Expert Opinion: Handbooks, encyclopedias, and textbooks often provide a good foundation or introduction and often include generalized information about a condition. While background information presents a convenient summary, it typically takes about three years for this type of literature to be published.

5.1.4 Evaluating Social Media

Although social media (for example, Twitter or Facebook) is generally treated as an object under study rather than a source of information on a topic, the prevalence of social media as communication and sharing platforms must be acknowledged. It’s important to be skeptical of these sources, especially for inclusion in a literature review. However, as with any other web resource,you can evaluate a social media posting for authenticity by asking the following questions:

- Location of the source – Is the author in the place they are tweeting or posting about?

- Network – Who is in the author’s network and who follows the account?

- Content – Can the information be corroborated from other sources?

- Contextual updates – Does the author usually post or tweet on this topic? If so, what did past or updated posts say? Do they fill in more details?

- Reliability – does the author cite sources and are those sources reliable? (Sheridan Libraries, 2017)

5.2 In Summary

Another way to think about evaluation of sources is to ask the 5W questions:

- What type of document is it?

- Who created it?

- Why was the material published?

- When was it published?

- Where was the resource published?

- How was the information gathered and presented? (Radom, 2017)

Locating sources for your literature review by using discovery layers, library catalogs, databases, search engines, and other search platforms may take a great deal of time and effort. Does everything you found and retrieved have value or worth to you as you write your own literature review? If the resource has not met the criteria above and you can’t justify its place in your literature review, it doesn’t deserve to be mentioned in your work. Include high-quality materials that are current, accurate, credible, and most importantly relevant to your research question, hypothesis, or topic.

Practice

Evaluate a Website

Watch this short video:

Using a search engine like Google, do a quick search for a topic that interests you. Select a website from your list of results and evaluate it using the elements of website evaluation listed earlier in this chapter.

- How did you find the website?

- What is the domain name (the URL) of the site?

- What can you learn about the author/s of the site?

- When was the site last updated?

- Is it accurate based on what you know about the topic?

- Are there references?

- Do you notice any bias?

- Is the site functional? (re links working? Or do they lead to non-functional pages?)

Evaluate a Book

Select a subject specific book or ebook that you can access quickly and evaluate it based on the ASAP criteria.

- Author

- Sources

- Age

- Publisher

Evaluate an Article

You can practice evaluation using the attached articles. You don’t need to spend a lot of time with the article, but see if you can identify each of the elements of evaluation. Remember the elements of evaluation for articles are:

- Authority/Credibility or Study Design for Nursing

- Accuracy

- Reliability/Objectivity

- Relevance

- Currency

- Scope and Purpose

For Education: Quality standards in e-learning: A matrix of analysis (Frydenberg, 2002).

For Nursing: Beliefs and attitudes towards participating in genetic research (Kerath et al, 2013).

Test Yourself

Check the Answer Key

For Nursing students: Your topic is the relationship between autism and vaccinations. Which of the two resources would you include in your literature review? Why?

- Hviid, Anders, Michael Stellfield, Jan Wohlfart, and Mads Melbye. “Association Between Thimerosal-Containing Vaccine and Autism.” Journal of the American Medical Association 290, no. 13 (October 1, 2003): 1763–1766. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=197365

- Chepkemoi Maina, Lillian, Simon Karanja, and Janeth Kombich. “Immunization Coverage and Its Determinants among Children Aged 12–23 Months in a Peri-Urban Area of Kenya.” Pan-African Medical Journal 14, no.3 (February 1, 2013). http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/14/3/full/

For Education students: Your topic is music therapy in kindergarten classrooms in the United States. Which of the two resources would you include in your literature review? Why?”

- Simpson, Kate, and Deb Keen. “Music Interventions for Children with Autism: Review of the Literature.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41, no. 11 (November 2011): 1507-1514.

- Bowman, Robert. “Approaches for Counseling Children Through Music.” Elementary School Guidance and Counseling 21, no. 4 (April 1987): 284-91.