Chapter 9 – Learning from the Homeland: An Emerging Process for Indigenizing Education

W̱SÁNEĆ School Board and Tye Swallow

SWETÁLIYE Marie Cooper was an Elder from W̱SÁNEĆ, a First Nations community near Victoria, BC whose territory extends through the Saanich Peninsula and nearby Southern Gulf Islands. She was, and always will be, cherished within her W̱SÁNEĆ community and throughout the greater education community because of her experience and her powerful, yet gentle welcoming way of expressing how important education is to her people. She is deeply missed and the impact she has had will continue to ripple well into the future. One of the first times I sat down with her over tea at her house, she said emphatically to me:

If you don’t even know where you come from, how can you even begin to know who you are! (personal communication, February 9, 2005).

For SWETÁLIYE, it was more a statement reflecting on what her Elders had told her. My understanding is that it is a relatively new phrase, brought on and punctuated by the realities of colonialism. For me, it continues to resonate as a powerful question because it provides curriculum and program developers a lens through which to view an Indigenous perspective.

This chapter, written over the past 15 years, is a collection of W̱SÁNEĆ voices spoken to me over that time. It is about a language revitalization movement in our school, and an opportunity taken to escape confining educational systems. In 2012 the W̱SÁNEĆ School Board (W̱SB) established a SENĆOŦEN immersion program from pre-school through to grade four. This significant work, represented by this story is, in part, about the journey of SENĆOŦENizing our school. It is hoped that by telling this story, other communities might be able to implement aspects of what we’ve learned into their own schools.

Assumptions, Confessions, and other Background

I am a British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Education certified, non-Indigenous male teacher and descendant of immigrants from the UK. I have also been teaching, facilitating, and working with adult learners at the Saanich Adult Education Centre (SAEC), part of the W̱SÁNEĆ School Board (W̱SB) for most of my educational career. The W̱SB provides educational services for the four W̱SÁNEĆ villages: W̱JOȽEȽP Tsartlip, SȾÁUTW̱ Tsawout, BOḰOĆEN Pauquachin, and W̱SIKEM Tseycum. We are a band operated, nominal role funded school that provides educational services at the preschool, K-10 and adult upgrading levels for First Nations students and uses a range of BC Ministry of Education prescribed curricula. The W̱SB has a long and storied history with many educational and language warriors—you’ll hear from many of them later in this chapter—and it is because of people like SWETÁLIYE that our school continues to innovate meaningful and relevant educational programming for W̱SÁNEĆ peoples.

From my earliest memories, I have lived within W̱SÁNEĆ territory. It is my home and I care for it deeply. I am humbled, honoured and thankful to know my homeland much deeper because of all the knowledge, wisdom, and teachings I have learned from W̱SÁNEĆ peoples in W̱SÁNEĆ places. It has been through a method of learning from the land and working with the community that has provided me with the opportunity to approach curriculum and program development, and its implementation, from a W̱SÁNEĆ perspective.

As an early career teacher, I was acutely aware that there seemed little need or reason, especially within public educational practices, for students to learn or know about their lands in ways their ancestors would have. The landscape of W̱SÁNEĆ has changed significantly since colonists arrived in the 1800’s, and this has had obvious repercussions on how people continue to relate to their homeland. From a W̱SÁNEĆ-centric educational perspective, this lack of meaningful cultural, linguistic, and ecological education has a huge effect on practice, understanding and sustainability.

The Canadian federal government’s recent commitment through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission poignantly reminds us of the reasons behind the erosion of Indigenous knowledge systems. The residential school education system is perhaps the most significant example of the harm that our colonial legacy has brought onto First Nations peoples and their knowledge systems. Although much has changed, this erosion of Indigenous knowledge continues in more subtle but equally detrimental ways. For example, funding for First Nations schools is determined through the use of mandated ministry prescribed curriculum; that is the law. Education, as it is predominantly practiced in our schools, is driven from a Western or Euro-centric perspective and includes a set of inter-related assumptions. These include the assumption that an efficient way to educate all people is to use pre-existing subject areas to meet pre-set objectives in a classroom, and to assess students on meeting those objectives, all within very structured and rigid timetables and yearly schedules. I have witnessed some positive changes, but this current system of education still exerts significant colonial influence and control.

Indigenizing Education

Indigenous scholars argue that the future of Indigenous education must shift emphasis toward indigenizing educational systems and structures (Battiste, 2000, 2013; Cajete, 1994, 2000; Castellano, 2014; Deloria Jr. & Wildcat, 2001; Kawagley & Barnhardt, 1998; Prakash & Esteva, 1998; Simpson, 2004). The “Indigenization of Education” necessitates taking the rights of Indigenous peoples as the highest priority, and to always work from a decolonizing theoretical framework. Kawagley and Barnhardt (1998) proposed that the culture of the education system, as reflected in First Nations schools needs radical change. This can be achieved, they say, by documenting, articulating, and validating local Indigenous Knowledge (IK) systems and using those to guide the development of curricula that reflect and reinforce those same knowledge systems. Simpson (2004) suggests we must protect, foster, and revitalize Indigenous processes for the transmission of IK to younger generations. This involves strengthening the oral tradition, teaching children how to learn from the land and how to understand the knowledge of the land in its cultural time and place. Educational programs and curricula, as such, must be land-based, use traditional language and “they must provide opportunities for youth to interact with Elders and traditional knowledge holders on Indigenous terms” (p. 380). Most importantly though, she emphasizes, “Indigenous Knowledge must be lived” (p. 381). How might education become lived?

A Sense of Place

Place is a persistent theme in Indigenous education; scholars (Barnhardt, 2008; Cajete, 1994, 1999a, 1999b, 2000; Deloria, 1997; Deloria & Wildcat, 2001; Corsiglia & Snively, 1997; Kawagley, 1995; Kawagley & Barnhardt, 1998, 1999; Simpson, 2004, 2011, 2013; Snively & Corsiglia, 2001; Turner et al., 2000; Williams & Snively, 2016) consistently connect place with identity and sense of belonging to homeland. Cajete (2000), a Tewa scholar, links an Indigenous notion of science with a deeply internalized sense of place. He calls this, “living in relationship…people understood that all entities of nature, plants, animals, stones, trees, mountains, rivers, lakes, and a host of other living entities, embodied relationships that must be honoured” (2000, p. 178).

An education of place provides a learning situation where both IK and Western Science have a meaningful and relevant context to draw from while at the same time providing all learners a sense of belonging to place. The notion of place is integral of any peoples’ worldview. How a sense of place develops, is respectfully learned or not, depends on how it is informed. Basso, in his book Wisdom Sits in Places (1996), prefers to use the term “sensing of places” (p. 109) because our sense of place is accrued and never stops accruing from lives spent sensing places. “Sensing of places,” as the term suggests, elicits using all your senses. David Abram (1996) puts it beautifully, “to enliven your senses” and making sense of your surroundings “is to make the senses wake up to where they are” (p. 265). Intrinsically, an education of place also allows for the inclusion of the more affective, intuitive, creative, and spiritual nature of the world, and our collective place in it (Peat, 1994; Cajete, 1994, 1999a, 1999b, 2000; Williams & Snively, 2016). Inclusion of the principles of ecology and eco-literacy, as articulated by alternative educators such as Capra (1998, 2002), Orr (1994, 2002) and Peat (1994) have contributed to this understanding of a more holistic and ecologically responsive education—one very much in-line with an education of place.

Most importantly though, as Michell et al. (2008), in reviewing a concept of Indigenous Science education reminds us, while Indigenous worldviews are similar in that they are place-based, they are, by the very same token, as diverse as the places from which they emanate. Fundamental in this description is that the land and the communities are both the source and the authority of the knowledge. Science education, as with all learning, cannot be learned entirely from the written word of a textbook in a classroom; it must be lived within the local community and experienced in a place-based (non-classroom) context.

Researching a Curriculum of Place—Purpose and Methodology

The primary purpose of this research was to explore a cultural concept of a sense of place and to open up possibilities of creating a local school-based program focused on themes that emerged from conversations with Elders, knowledge holders and students. Secondly, the research was designed to explore the extent to which a sense of place as a construct might contribute conceptually and methodologically to a place-based curriculum development process, such that a culturally appropriate framework might be established and articulated in collaboration with First Nations communities (Swallow, 2005).

Research within a First Nations community requires that certain protocols be followed in order to maintain the respect of the people within the community (LaVeaux & Christopher, 2009). The process of building a research methodology around community input and design resembles what is known as Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). LaVeaux and Christopher (2009) referencing Israel et al. (1998) identify several aspects of CBPR that have been successful in research with Indigenous communities. They highlight research practices that involve:

- understanding community as a unit of identity, building on strengths and resources of community,

- collaborating in all aspects of research, integrating knowledge and action for mutual benefit,

- promoting co-learning and empowerment processes that attend to social inequalities,

- a cyclical and iterative process, addressing research issues from a positive and ecological perspective, and

- disseminating findings and knowledge gained to all partners.

With the intention of openness and flexibility, the methodology unfolded as I talked with Elders and community members. SWETÁLIYE suggested we set up a local advisory committee. This group proved integral in the development of the research questions and design, interview protocols and the gathering of participants. The research was conducted in two phases. First, a feast took place, to inform community members about the research and to ask for guidance, which resulted in a gathering of Elders and other interested community members. The second phase of the research consisted of semi-structured personal interviews with Elders, language teachers and former students. Questions revolved around an evolving understanding of a W̱SÁNEĆ sense of place and notions of what this might mean in science education. Twelve people were included in the original research conversation, which provided the dialogue for synthesis into emerging themes.

What is “Knowledge of Most Worth?” A W̱SÁNEĆ Perspective

The idea of researching the process of curriculum development and implementation was used in the overall framework. As such, perhaps a fundamental question for any curriculum and its purpose is to determine “what is knowledge of most worth?” (Marsh & Willis, 1995, p. v). Research into answers from this question provided convincing evidence of what W̱SÁNEĆ peoples felt should be in science curriculum and illuminated what I came to identify as central aspects of a W̱SÁNEĆ sense of place.

The quotes that follow provide a representation of the themes that emerged from interviews. Specific knowledge is left out, but the importance behind that knowledge comes through beautifully.

SWETÁLIYE believed fully in supporting public education for her people and how it could bridge gaps in understanding between her people and the larger society (Figure 9.1).

However, from a W̱SÁNEĆ perspective, she said:

Unless we begin to educate our people fully, holistically, unless our young ones begin to find their place, to see, hear, feel and experience our territory, to learn who we are as Saanich people, then we risk losing that knowledge” (personal communication, February 9, 2005).

Mavis Henry, long-time Tsawout educator and W̱SB member, reiterate the above concerns and expands on what that knowledge means to her people:

We need to understand and sustain our knowledge of the land, how we used it, that it provides gifts, and why they are considered gifts. We need to remember to respect these gifts by using them, if not then we risk losing that knowledge. We have a responsibility to remember that (personal communication, January 12, 2005).

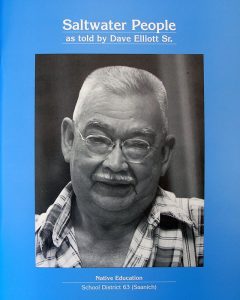

STOLȻEȽ John Elliott Sr. is a fluent SENĆOŦEN speaker, language champion and resident Elder and teacher at the W̱SB. His knowledge of his peoples’ heritage and place on this land is invaluable (Figure 9.2).

He explains W̱SÁNEĆ knowledge this way:

We need to maintain those things that the old people talked about, to take care of the land, respect it now and for the future. Our culture is all related to our land and our territory and within it all our teachings. We need to know who we are, what makes us W̱SÁNEĆ (personal communication, February 8, 2005).

One of the pertinent findings of this research was the fact that very little, if anything, of what W̱SÁNEĆ peoples indicated was of most worth, is currently prescribed in any formal public school curriculum. Former students all reported this in one way or another. Kelly Paul, a former student and W̱SÁNEĆ activist expressed it this way to me:

What are we taught to value in school? I wasn’t taught the importance of my culture or my language in public school. How are we to identify ourselves without our traditions? Instead, we learn to value what they [Ministry of Education] value (personal communication, January 14, 2005).

For students to find meaning and relevancy in what curriculum prescribes, knowledge of their community and culture and what they feel is of most worth must be a significant part of their whole educational experience. STOLȻEȽ says:

The way we are teaching and learning does not fit. Students are learning in a false environment. We lived on the land and learned from it. The land was our school (personal communication, February 8, 2005).

How Does “Knowledge of Most Worth” Relate to Science Education?

When asked how science education might be able to assist students gain knowledge of what their community feels is of most worth, some participants responded by asking their own questions. Glenn Jim, Tseycum community educator, suggested:

Students need to learn the impacts and consequences of environmental actions that relate to their communities like run-off from farms and development. Our traditional gathering grounds are polluted. Why? How do we fix it? (personal communication, February 23, 2005)

Mavis Henry asks a very relevant question:

What is the science in our knowledge? Use science to approach our reasoning. Find the science in everyday life, holistic knowledge, like gathering, catching our food and preserving it. Search out ways where science helps day to day. Use science for change to reduce health risks for our people (personal communication, January 12, 2005).

Josephine Henry, a former student (now enrolled in a B.Ed program at UVic) and current SENĆOŦEN Language Revitalization Apprentice, suggests how this can be achieved in a culturally meaningful way:

We need to learn by incorporating both sides of an issue, by learning science and with an Elder. How we used the land and what it represented for us then, and how it can be used now? (personal communication, November 29, 2004)

W̱SÁNEĆ peoples’ relationships within their homeland encompasses belief systems, it also captures a context of inquiry of their notion of science. It was practiced in living with their homeland. STOLȻEȽ expresses it this way:

Our science lies in knowing our ancient connections to land. It is also where our spirituality is. I believe we bring a lot of awareness in the way we educate, the way we relate to our land and territory (personal communication, February 8, 2005).

An important question for education becomes: How can we structure educational experiences such that students have opportunity to build long lasting, culturally respectful and meaningful relationships with place and to encourage responsibility for maintaining long-term sustainable relationships? And how might incorporating science education help us investigate and express those relationships?

Regenerating Place-based Relationships

Themes that emerged in my conversations with the W̱SÁNEĆ peoples reveal knowledge associated with homeland along with significant essentials of that knowledge: Elders as knowledge carriers; the SENĆOŦEN language and place-names; W̱SÁNEĆ history, teachings, ceremony, sense of belonging and identity—they provide a cultural context to inform curriculum development. Meaningful and relevant education, including science education, suggests relearning relationships with “a sense of place”—a perspective that will provide ecologically grounded experiences, exposure, and rediscovery; this is true regardless of culture. However, most importantly this research strongly indicated that place-based experiences need to be delivered within—and for—a cultural context.

Land development has impacted the traditional territory of W̱SÁNEĆ significantly—agriculture and the inevitable pollution and the ecological degradation that results have fundamentally altered W̱SÁNEĆ people’s relationships with their homeland. Fishing, hunting, and gathering food and other resources are no longer the necessity, nor are they available as they once were. As a result, ceremonial and other spiritual relationships that relate to these practical needs are inherently altered and to varying extents not practiced anymore. However, this reality does not suggest that these relationships are no longer important in today’s world. Indeed, W̱SÁNEĆ people tell me that the meanings behind these traditional relationships are absolutely essential for cultural survival and sustainability. If spiritual and practical applications of culturally inherent relationships to place have been forced to change over time, can new relationships with the land be regenerated to recapture those important and essential meanings into a current context?

Place Names

Indigenous place names convey the importance of place because they have direct references to specific sites within a traditional territory. The name a place carries forms a shared body of knowledge that reaches deeply into other cultural spheres (Basso, 1996). XETXÁṮTEN Earl Claxton Jr. notes: “Our place-names are very important in identifying our homeland because each of those places contains a history, an important meaning or a teaching. It is more than just the name of a place” (personal communication, September 22, 2004) (Figure 9.3).

The history, teachings, and meanings referred to above represent a significant source of cultural knowledge. STOLȻEȽ states: “These teachings provide a sense of identity as W̱SÁNEĆ people. They provide a connection to place. Our people learn something from these places. They are learning and passing on important cultural values. This is W̱SÁNEĆ thinking” (personal communication, February 8, 2005). Place-based experiences provide opportunities to draw from spiritual and practical applications of culture through the stories, teachings, and/or other important references to history, people, and place. Vern Jacks Jr., Tseycum, community educator, expresses it succinctly: “We need to remember; the old people left something for the young ones at these places” (personal communication, October 14, 2004).

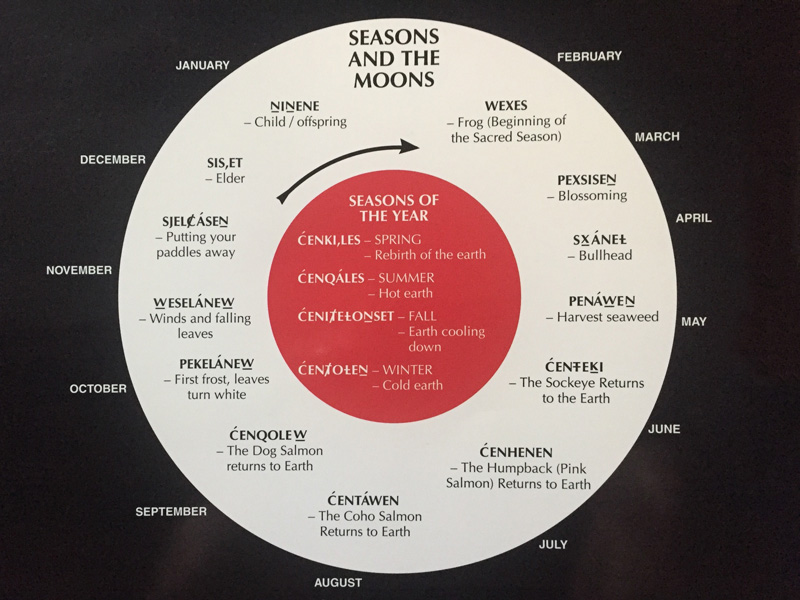

Based on emerging themes, we approached our Elders’ cultural advisory group and discussed the creation of a pilot project. Culturally appropriate learning outcomes were established, based on the outcomes of the original research, but purposely left open to emergence. Together we determined that several cultural and ecological activities could be utilized to contextualize a program that grounds learning, on W̱SÁNEĆ terms, in and from place. These outcomes revolved around educating students through traditional teachings, history, and stories with Elders; language learning and application with fluent/proficient speakers; engaging in traditional use values of the environment; ecologically informing students through field experiences; eco-cultural restoration projects in places; and outdoor recreation—all wrapped around a traditional W̱SÁNEĆ year (Figure 9.4).

ÁLEṈENEȻ—Learning from Homeland

ÁLEṈENEȻ means “homeland” in the SENĆOŦEN language. ÁLEṈENEȻ—Learning from Homeland was a curriculum development research project that was created and delivered by the SAEC as an extra-curricular course in 2006. The intent of the pilot project was simply to bring people and place together and to learn from those experiences. Centred on culturally significant place-names within W̱SÁNEĆ territory, participants learn through direct experience by visiting cultural places. Most importantly, it is a living curriculum, and has since experienced several iterations as it has been left open to emergence over the years.

For the first three years, the program ran in May and June, half-days Tuesday through Thursday and a full day on Fridays. This format allowed for longer-term intensive experiences in home places and out on the land for participants. Numerous other guest speakers and organizations, both from within and allies outside of the W̱SÁNEĆ community, would share their work with us and many continue to collaborate with us.

We have a huge map of SENĆOŦEN place-names in the hallway of our school. It was created as part of a successful Saanichton Marina court case in the 1980’s in which W̱SÁNEĆ Elders came together and created a place-name map, to claim the extent of their territory. Saltwater People (Elliott, 1990), is a wonderful and powerful collection of SENĆOŦEN place names, and it offers a fascinating glimpse into a W̱SÁNEĆ sense of place (Figure 9.5)

We can explore and learn about literally hundreds of place names. Up to this point, many of these places have been visited by students in our program: L̵ÁU,W̱EL,ṈEW (place of refuge), SṈITC̸EL (place of Blue Grouse), KENNES (whale), and PKOLS (white head) one of three places with that name that demarcate W̱SÁNEĆ territory (Elliott, 1990). They all have realms of significance from the sacred to practical. Due to the physical character of the Saanich Peninsula, each place can be accessed by a variety of ways, by trail, water, and/or road. Participants can canoe, kayak, hike, or drive to each place, adding variety to the way a place can be approached and experienced. Elders and several other knowledgeable community members culturally inform learning experiences through the telling of traditional history as well as the stories and teachings associated with the place (Figure 9.6).

Elders and guest speakers are provided a suggested list of questions that can be used to guide the experience:

- What does the place name mean?

- Are there stories connected to the place?

- What is its history?

- How can we interpret the place name today?

Awareness of ecological relationships naturally guides experiences. For example, in place we ask:

- How can we describe the ecology of the place?

- What are the SENĆOŦEN names of the plants and animals of the place?

- How might SENĆOŦEN describe these relationships?

In addition, sustainability factors are discussed and questions might include: How did the ancestors live sustainably with this place? How can we live sustainably in place again? With sustainability as the focus, we ask questions related to housing, food security, water, energy, and waste management.

Eco-cultural restoration activities that are locally meaningful to the community are conducted in an ongoing seasonal basis according to the W̱SÁNEĆ Year (Claxton & Elliott, 1993). The sites where these activities occur become important “classrooms” for schools and communities to begin reclaiming culture through reengagement. These activities take place outside the ministry mandated school year-time frame and are readily accepted by the community. There are very few places on the Saanich Peninsula where a look back in time is possible, but fortunately a few of these places have been preserved as parks and protected lands. These are truly beautiful ecosystems; they are Indigenous within W̱SÁNEĆ territory. One particular example, significant to W̱SÁNEĆ and neighbouring nations, is KȽO,EL camas lily—Camassia leichtlinii or quamash. The bulb of this perennial flower was a starch staple and trade item for many tribes in the Pacific Northwest region. Traditionally, families tended these places as gardens and harvesting was a seasonal social and cultural activity (Turner & Hebda, 2012). Currently, the ecosystems that support this plant, and many other culturally significant species, are severely threatened by land development and other invasive plant and animal species. Although KȽO,EL is not the staple it once was, there are several places, including ones with place-names, that have KȽO,EL ENEȻ (places of camas). We have been interacting with these places in an attempt to rebalance these ecosystems through the removal of invasive species, such as Scotch broom and gorse, English ivy, daphne, bull thistle and replanting native species. such as, KȽO,EL and other perennial species, native shrubs, climax tree species ĆEṈÁȽĆ (Garry oak), and ḰOḰE,IȽĆ (arbutus). Several First Nations community based leaders, academics, and allies have been working towards restoring and revitalizing these places (Beckwith, 2004; Corntassel & Bryce, 2012; Turner & Hebda, 2012; Turner, 2014a, 2014b). It is an ecosystem ripe for school/community engagement and an example of where scientific inquiry and action can be implemented.

Other more recent place-based eco-cultural restoration projects revolve around a traditional clam garden at a place called ȾEMÁȻES (Russell Island). In partnership with Parks Canada and Royal Roads University, students and community members are revitalizing this site and others through traditional practices, turning over of the beach and re-establishing the ancient rock wall. Parks Canada helps provide a host of scientists and community activists to guide scientific enquiry on how traditional activity on the beach affects changes in productivity (Groesbeck et al., 2014). Traditional cultural activities and crafts include preserving clam necklaces and rattles (Figure 9.7).

Another site/classroom is ȾIKEL (Figures 9.8 and 9.9)—a wetland that was an integral site for gathering medicines as well as a culturally significant plant and climax tree species called SX̱ELE,IȽĆ (Pacific Willow).

Restoring traditional gathering grounds through ecological practice, while at the same time relearning the traditional practice of making nets from fibre, is another example of a meaningful educational practice (Figure 9.10).

For a more detailed description and illustration of the reef net technology, see Claxton & Elliott (1994) and Snively & Corsiglia (2016).

ṮEṮÁĆES — “Relatives of the Deep”

A highlight and culminating activity was a multi night kayaking and canoe trip through the ṮEṮÁĆES (relatives of the deep), part of traditional W̱SÁNEĆ territory in the southern Gulf Islands (Figure 9.11). Students, guides, and guest speakers were co-participants, and together planned a traditional route and camped overnight at W̱SÁNEĆ First Nations reserves.

Participants are responsible to research a particular place-name and tell their stories as we travel. For example, we travelled from S,DÁ,YES (wind drying) referring to a happy place for wind drying salmon, to ȽO,LE,ĆEN (place to leave behind), on to SXEĆOŦEN (you can see where your mouth is) and finally to W̱EN,NÁ,NEĆ (bay facing Saanich). Elders, community members, and children also join us by ferry at several of these places. Elders lead cultural activities that involve cedar root and bark gathering, fire building, clam digging, preparing, and smoking, as well as preparing salmon in a traditional way. Together a feast is shared (Figure 9.12).

Reflection as Assessment

All experiences are intended for participants to learn about themselves in relation to their homeland. As such, reflection is an integral component and outcome of the program. In order to facilitate personal reflection, time is provided at each place-name of cultural significance for participants to write about and share how each experience made them feel, what they learned, and what they will carry with them into the future. During our third year we published a collection of participant voices in ÁLEṈENEȻ—Learning from Homeland and other educational research essays (Saanich Indian School Board, Guilar, & Swallow, 2008). The following quotes are examples of participant reflections:

In many ways, I have reconciled with our land, our relationships, and our connection with our traditional spirit. This trip has reawakened something that has been dead for a long time. Our reconnection to land is so vital to our existence and survival. At these places, I felt like I was being welcomed. (Rhonda Underwood, p. 278)

Part of the rediscovery I felt was my reconnection to the land. As a child, I was taught about how this land is ours, how it is alive, and how to live and take care of it. I realized how many ways I was out of balance with what I had learned about our land. My thoughts and actions were from a borrowed way of life. The reconnection to our islands was like being home, like learning a close reenactment of how people lived. Kayaking felt like a reconnection to the water, it was a great feeling. (Tracy Underwood, p. 152)

I think the way I look at my territory has changed dramatically—the way I look at plants, their SENĆOŦEN names, our environment, and their meanings. I look where I step now. I have a much greater appreciation of where I am. (P. J. Sam, p. 277)

I feel more connected to the land and the use of our territories. Seeing them made me envision our ancestors, what they did, and what my role would have been. It would be very different from today. Every place we went to had a story. Our people had a use because the name tells us that. Like our ṮEṮÁĆES (islands). I know them now in our words. The SENĆOŦEN names provide more depth. I feel like I have been given a gift. I need to remember to live what I have learned. (SDEMOXELTEN Ian Sam, former Language Revitalization Apprentice and current Immersion Language Teacher, p. 278)

I have always talked about community and land. I have always had a desire to take a lead in protecting our land. This class has provided opportunity to talk with and be with people who share similar thoughts and beliefs. This group and the energy it carries will move somehow in the future. It has been an uplifting feeling. (MENEŦIYE Elisha Elliott, former Language Apprentice and current Immersion Language Teacher, p. 281)

I have been dreaming in our language. I know I have so much more to learn. I have spent my whole life here and am just beginning to learn our language. Our strength is within our traditions, language, and culture. (PIȾELÁNEW̱OT Samantha Etzel, Tsawout Educator, p. 286)

This course has been like becoming W̱SÁNEĆ. We have a long way to go, but I see the possibility of incorporating our philosophy and ways of harmonizing with our environment. I realize now we are way out of balance. We need to take a step back and look at things and get critical as a way of transformation. (PENÁĆ David Underwood, former Language Apprentice and current Immersion Language Teacher, p. 278)

Barriers to an Emergent Curriculum Development Process in Public Schools

Although there are always exceptions, it is easy to argue that contemporary educational systems exacerbate a fragmented and mechanistic philosophy that views knowledge as abstract and disconnected from students’ lived experiences (MacQuarrie & Smith, 2009; Orr, 1994, 2002). The reality these forms of education reflect is the same “dominant worldviews [that] permeate and (re)construct human consciousness to such an extent that we scarcely question their validity” (MacQuarrie &Smith, 2009, p. 33), or their limitations. MacQuarrie and Smith (2009) suggest that this problem is insurmountable if we continue responding in ways that only tinker with existing western education systems and structures. There is no simple fix, they say, because it requires nothing less than a change in the way an educational system forces us to view the world.

While there is increasing willingness in the public-school system to use locally and more Indigenous developed curricula, there continue to be barriers. The fourth iteration of our ÁLEṈENEȻ program involved the creation and development of a school board authorized course for W̱SÁNEĆ learners at the local public high school that serves the W̱SÁNEĆ community. Even though the program received significant support from both the W̱SB and local school district, creating the space to implement ÁLEṈENEȻ proved to be a difficult task. Due in large part to conflicts between the two educational systems, primarily an inflexible timetable and packed student schedule, the high school students were only able to participate at 20 percent of what had been done previously. Attrition was high as students fell behind in their other “core” courses and were not permitted to participate in many events. Admittedly this was only one try, but the context and timeframe that worked so well in previous years was severely fragmented. I bring this to the reader’s attention to stress the point that public school systems tend to be extremely rigid systems. Ministry standards exist, for good and for bad depending on a position, but they limit change. By succumbing to the pressures and enforcement of this colonially inspired educational system, local First Nations communities lose significant authority to self-determine education.

Recent attempts by the BC Ministry of Education (2015/16) to redesign the K to 12 curriculum by embedding more Indigenous perspectives and resources at each grade level and subject area, is a huge step towards Indigenizing education for public school systems. From a First Nations perspective, however, where there is a greater ability to adapt and change, it is still considered tinkering only. The argument here is not to discourage attempts to do better and increase Indigenous content in our BC Ministry of Education’s Prescribed Learning Outcomes, but rather to emphasize that much more can be done at the community level. After all, it is not a priority of the Ministry of Education to help revitalize Indigenous languages and cultures. The argument is to encourage individual communities to not wait for change or leadership from the ministry but to make change for themselves; don’t ask for permission to take back control of education.

Rebalancing an Education System

One way to counter some of this ongoing colonial influence and further Indigenize control over education, is to use current ministry Prescribed Learning Outcomes, but utilizing a language immersion context through a traditional language medium like the Māori in New Zealand and the Hawaiian people have been championing for well over 30 years. This notion of control is being utilized at a few Band-Operated Schools in BC (e.g., Chief Atahm School in Chase, Mount Currie, W̱SB). Although there are 125 band operated schools and adult centres in BC (INAC, 2013), the sad and stark reality is that almost all BC languages are critically endangered or sleeping (First Peoples’ Cultural Council, 2014). As such many communities do not yet have the language capacity to invest in this work.

Language Apprenticeships and the Importance of Adult Education—Towards SENĆOŦENization

Indigenizing the entire context (the why, when, where, what and how) in which we actually practice education needs significant transformation if it is to reflect culturally relevant ways of knowing and being. Our experience suggests we cannot fit this learning context, as it has emerged in our ÁLEṈENEȻ program, into a fixed, pre-determined educational system. It loses its flexibility and adaptability and as such, its ability to emerge in any culturally meaningful new way. In our case, the learning context was created first, ÁLEṈENEȻ—Learning from Homeland, and our timetable re-worked to facilitate its development at the adult level where following mandated curricula or an inflexible timetable is not as restricting. Assessment has been about finding ways to culturally improve and expand the program and student learning. Program outcomes are about holistic and interconnected relationships between people, places, and an educational culture that can continue to evolve on its own terms.

It is important to note that our experience indicates that adult participants respond at a deeper level to these experiences. It has been clear from the beginning that the strength of the program, and any potential movement forward, lies within the participants who care deeply about revitalizing their languages and cultures. Community-based adult education programs can benefit significantly from partnering with universities in the development and delivery of Indigenous Language Revitalization programs such as the program at the University of Victoria. Their support, along with allies in linguistics, has been essential in realizing the outcome of Indigenization and actualizing SENĆOŦENization.

SȾÁ,SEN TŦE SENĆOŦEN—Developing Language Capacity

In 2009, the W̱SB initiated a language revitalization department—the SȾÁ,SEN TŦE SENĆOŦEN. Up to that point in 2009, 44 community members (24 female and 20 male) aged 16 to 56 had contributed to our ÁLEṈENEȻ program through their participation. As such, we knew there was much interest to begin language revitalization apprenticeships; they were primed and ready to take on these important roles and were acutely aware of the critical state of their heritage language, and the declining number of proficient-fluent Elders. We began by offering paid apprenticeships for six students who had, or would commit to becoming certified teachers or early childhood educators. We funded our program through commitment from the W̱SB and ongoing grant applications from organizations such as First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC). Apprentice tasks were to shadow our three existing Elder language teachers, spend time with other proficient Elders in weekly gatherings, help develop language curriculum and other language revitalization duties. They also participated in more traditional Mentor-Apprentice relationships (Hinton, 2002; FPCC, 2012). A challenge we continue to face and that most BC communities will need to overcome is a lack of fluent Elders. In order to counter this, we often doubled and tripled up apprentices with mentors. And, as more needs/wants became exposed, our collective jobs became to find ways to fill those needs. There are endless needs and wants in this work. The key is to prioritize and keep expanding the language capacity to accomplish that work.

In the years since we have provided paid language apprenticeships to 22 W̱SÁNEĆ people of all ages and that number grows yearly as our language capacity increases. Most of that first cohort of apprentices are now BC ministry certified teachers or early childhood educators working in our school. These language revitalists, as we call them, now carry our place-based curriculum forward in our SENĆOŦEN LENOṈET SCUL,ÁUTW̱ preschool through Grade four immersion survival school—our goal is to continue providing immersion/bilingual programming up to grade 12.

ÁLEṈENEȻ is a core context (not content) area through which language immersion teachers teach science, social studies, math, P.E., and other language related content through the medium of SENĆOŦEN. Much like several Nature Kindergarten programs gaining support in the Greater Victoria region—another meaningful Indigenizing step—students spend extended times, several days per week learning from outdoor place-based contexts in their homeland. An overriding objective of our SȾÁ,SEN TŦE SENĆOŦEN program continues to focus on the development of SENĆOŦEN language curriculum connected to place to be infused into the overall programs of the W̱SB. SX̱EDŦELISIYE Renee Sampson, is a SENĆOŦEN immersion kindergarten teacher in the LENOṈET SCULÁUTW̱. She has a Masters degree in Indigenous Language Revitalization and is also a former student of our ÁLEṈENEȻ program. When asked how she utilizes ÁLEṈENEȻ with her students, she says:

We focus on connecting our children, our babies, to our homeland outside the four walls of a classroom, to use our senses to really feel what our Earth encompasses. I think a reality is many of our W̱SÁNEĆ children don’t play outside or even ever get dirty. Like most children these days, they’re gaming inside and rarely, if ever, get dirty, play in the forest, jump in the leaves, climb the hills and mountains in our territory.

The science related PLO’s in Kindergarten relate to our senses and so are very relatable to our connections to nature and our homeland. We exercise through playing outside in a natural state. We try to subtly get them to stop and take in the beautiful scenery of our forests, smell the light rain on the moss, to use their senses to feel what our ancestors would have felt, to feel the plants and trees that would have been so very important, essential to our ancestors. We sit in silence, listen with our ears, our hearts, to the birds, winds through the trees. Then we connect these feelings with the telling of our origin stories.

We use our senses to take in our surroundings, but we do it in a beautiful way that opens up deep windows into a W̱SÁNEĆ way of understanding our world. When we use the names of sacred beings (plants, trees, animals, places in our territory) we give them respect. Giving them respect through prayer, honouring, acknowledgment; thanks gives it more life. Our children, they gain a deep identity.

Other science areas such as inquiry, prediction of weather, life cycles of salmon for example, these are very relatable to our Worldview. Learning the stages of a salmon and releasing them at SELEḴTEȽ, we then complete this cycle through the catching, cutting, smoking, and tasting of our salmon. Learning the life cycle of a frog, their habitats etc., we learn those through our own words, our language that captures who we are in this world. Then we can connect those experiences in our classrooms. (May 16, 2017)

Conclusion

Towards Truth and Reconciliation through Education

Anyone who knew SWETÁLIYE understands how important the idea of Holistic Education was to her. In her words:

We need to begin again to understand the holistic place of our people. Our connections to our land are not just physical. It is all encompassing. Our language, place-names, our heart, our soul, our spirit, our livelihood, our way of living and being is tied up in our land. It has taken me a long time to understand fully, the impact our knowledge of our land and territory means to the holistic place of our people (personal communication, February 9, 2005).

This idea of holism and holistic education, still sits with me always. ÁLEṈENEȻ was ultimately about bringing people and place together, and science education can learn and give much for this “purpose” of educating. Our SȾÁSEN TŦE SENĆOŦEN language revitalization work has seen huge growth, but an enormous amount of work—generations of it—still remains. Our efforts suggest that curriculum and program developers at First Nations controlled schools, in collaboration with the community and in the community, explore processes for gathering and facilitating place-based knowledge education at the adult curriculum level in order to generate interest and offer the possibility of providing language revitalization apprenticeships. They can then leverage those efforts through infusion of a Language and Culture Revitalization movement in a band controlled school.

Communities need to move forward with this work—and now. It takes a growing team of dedicated people who all share a common vision, and a passion for revitalizing their heritage languages and cultures to sustain this effort. Language Revitalization involves a monumental amount of work because it is arguably an Indigenous communities’ most valuable remaining asset and it requires significant investment. If we are serious about Truth and Reconciliation; communities, schools, universities, and governments must all contribute towards this effort. It needs to be nested and cultivated at the community level. A community-controlled school is a meaningful and fruitful place to “purpose” – creating the space – for education and educating.

Emergence and transformation are themes that run deep through many W̱SÁNEĆ stories and embedded within these stories is a philosophy of change and adaptation to new realities. Indeed, W̱SÁNEĆ translated means “the Emerging People.” In the flood story, it is said that when the top of L̵ÁU,W̱EL,ṈEW̱ (Mt. Newton) became visible, someone said: “NI QENET TŦE W̱SÁNEĆ” (Look at what is emerging!).

REFERENCES

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than human world. New York, NY: Random House.

Barnhardt, R. (2008). Creating a place for Indigenous knowledge in education: The Alaska Native Knowledge Network. In D. A. Gruenewald & G. A. Smith (Eds.), Place based education in the global age: Local diversity (pp. 113-133). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Basso, K. (1996). Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Battiste, M. (2000). Maintaining Aboriginal identity, language, and culture in modern society. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 192-208). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich.

Beckwith, B. (2004). “The queen root of this clime”: Ethnoecological investigations of blue camas (camassia leichtlinii (Baker) Wats., C. quamash (Pursh) Greene; liliaceae) and its landscapes on southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia (Doctoral dissertation). University of Victoria, Victoria, BC. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1828/632

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of Indigenous education (1st ed.). Durango, CO: Kivaki Press. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED375993.pdf

Cajete, G. (1999a). Reclaiming biophilia: Lessons from Indigenous peoples. In G. Smith & D. Williams (Eds.), Ecological education in action: On weaving education, culture and the environment. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Cajete, G.A. (1999b). Igniting the sparkle: An indigenous science education model. Skyland, NC: Kivaki Press.

Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Capra, F. (1998). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Capra, F. (2002). The hidden connections: A science for sustainable living. New York NY: Anchor Books.

Castellano, M.B. (2014). Indigenizing education. Education Canada Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.ceaace.ca/blog/marlene-brant-castellano/2014/06/2/indigenizing-education

Claxton, E. & Elliott, J. (1993). The Saanich year. W̱SÁNEĆ: Saanich Indian School Board.

Claxton, E. & Elliott, J. (1994). Reef net technology. W̱SÁNEĆ: Saanich Indian School Board.

Claxton, N. X-T (2004). ISTÁ SĆIÁNEW̱, ISTÁ SX̱OLE—“To fish as formerly”: The Douglas Treaties and the Saanich reef net fisheries. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria.

Corntassel, J. & Bryce, C. (2012). Practicing sustainable self-determination: indigenous approaches to cultural restoration and revitalization. Brown Journal of World Affairs. 18(2), 151-162.

Deloria, V. Jr., & Wildcat, D.R. (2001). Power and place: Indian education in America. Denver, CO: Fulcrum Resources.

Elliott, D. Sr. (1990). Saltwater people: A resource book for the Saanich Native studies program. Saanich, BC: School District 63.

First Peoples’ Cultural Council [FPCC] (2012). B.C.’s Master-apprentice language program handbook. Victoria, BC: First Peoples’ Cultural Council. Retrieved from http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/MAP_HANDBOOK_2012.pdf

First Peoples’ Cultural Council [FPCC] (2014). Report on the status of B.C. First Nations languages (2nd edition). Victoria, BC: First Peoples’ Cultural Council. Retrieved from http://www.fpcc.ca/files/pdf/language/fpcc-languagereport-141016-web.pdf

Groesbeck, A.S., Rowell, K., Lepofsky, D., Salomon A.K. (2014) Ancient Clam Gardens Increased Shellfish Production: Adaptive Strategies from the Past Can Inform Food Security Today. PLoS ONE 9(3): e91235. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091235

Hinton, Leanne (2002). How to keep your language alive: A commonsense approach to one-on-one language learning. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books.

Kawagley, A.O. (1995). A Yupiaq worldview: A pathway to ecology and spirit. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Kawagley, A.O., & Barnhardt, R. (1998). Culture, chaos and complexity: Catalysts for change in Indigenous education. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Kawagley, A. O., & Barnhardt, R. (1999). Education Indigenous to place: Western science meets Native reality. In G. A. Smith & D. R. Williams (Eds.), Ecological education in action: On weaving education, culture, and the environment (pp. 117-140). New York, NY: SUNY Press.

LaVeaux, D., & Christopher, S. (2009). Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 7(1), 1-25.

MacQuarrie, J., & Smith, G. D. (2009). Placing pedagogy and curriculum within an ecological worldview. SFU Educational Review, 1, 30-40.

Marsh, C., & Willis, G. (1995). Curriculum: Alternative approaches, ongoing issues. NJ: Prentice Hall Inc.

Michell, H., Vizina, Y., Augustus, C., & Sawyer, J. (2008). Learning Indigenous science from place: Research study examining Indigenous-based science perspectives in Saskatchewan First Nations and Métis community contexts. Saskatoon, SK: Aboriginal Education Research Centre, University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved from http://iportal.usask.ca/docs/Learningindigenousscience.pdf

Orr, D. W. (1994). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Orr, D.W. (2002). The nature of design: Ecology, culture, and human intention. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Peat, F. D. (1994). Lighting the seventh fire: The spiritual ways, healing, and science of the Native American. New York, NY: Birch Lane Press.

Prakash, M. S., & Esteva, G. (1998). Escaping education: Living as learning in grassroots cultures. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Saanich Indian School Board, Guilar, J. & Swallow, T. (2008). ÁLEṈENEȻ: Learning from place, spirit and traditional language. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 2(2), 273-293.

Simpson, L. (2004). Anticolonial strategies for the recovery and maintenance of Indigenous knowledge. American Indian Quarterly, 28(3/4), 373-384. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0107

Simpson, L. (2011). Dancing on our turtle’s back: Stories of Nishnaabeg re-creation, resurgence and a new emergence. Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books.

Simpson, L. (2013). The gift is in the making: Anishinaabeg stories. Winnipeg, MB: Highwater Press.

Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd edition). London, EN: Zed Books.

Snively, G., & Corsiglia, J. (2001). Discovering Indigenous science: Implications for science education. Science Education, 85(1), 6-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-237X(200101)85:1<6::AID-SCE3>3.0.CO;2-R

Snively, G., & J. Corsiglia. (2016). A window into the Indigenous science of some Indigenous peoples of Northwestern North America. In G. Snively & L. Williams (Eds.), Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science, Book 1 (pp. 105-125). Victoria, BC: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/knowinghome/

Swallow, T. (2005). A sense of place: Toward a curriculum of place for W̱SÁNEĆ people (Masters thesis). University of Victoria, Victoria, BC. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1828/819

Turner, N. J. (2014a). Ancient pathways, ancestral knowledge: Ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America, Volume 1: The history and practice of Indigenous plant knowledge. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Turner, N. J. (2014b). Ancient pathways, ancestral knowledge: Ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America, Volume 2: The place and meaning of plants in Indigenous cultures and worldviews. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queens University Press.

Turner, N. J., & Hebda, R.J. (2012). Saanich ethnobotany: Culturally important plants of the WSANEC people. Victoria, BC: Royal BC Museum

Turner, N. J., Ignace, M. B., & Ignace, R. (2000). Traditional ecological knowledge and wisdom of Aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. Ecological Applications 10(5), 1275-1287. https://doi.org/10.2307/2641283

Williams, L. & G. Snively. (2016). “Coming to know”: A framework for Indigenous science education. In G. Snively & L. Williams (Eds.), Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science, Book 1 (pp. 129-146). Victoria, BC: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/knowinghome/