Chapter 4 – The Metaphor Interview and First Nations Students’ Orientations to the Seashore

Gloria Snively

I wish to gratefully acknowledge Chief Kwaxalanukwa‘me’ ‘Namugwis Bill Cranmer and all those at the ‘Namgis Band Council for supporting this research, in particular Yakudtlas`dzi George Speck and the late Hayałkan Lawrence Ambers. Special thanks are also extended to Ga‘axstalas Flora Cook, principal of the Alert Bay Elementary School for supporting the research study from the outset, and for providing me with continuous guidance and support. Special thanks to the Kwak’wala language and culture teachers, ‘Mam’xu’yugwa Auntie Ethel Alfred, Gwi’molas Vera Newman, Tłalilawikw Pauline Alfred, and Tidi Nelson, who provided much needed advice and for sharing their considerable knowledge and wisdom with myself and the class of Grade 6 students. A very special thank you to all the students who took part in this study, for sharing their experiences and reflections, and for allowing their stories to be told for our benefit.

As a newcomer and woman who has enjoyed working with First Peoples for over 40 years, I have attempted to present the stories of the ‘Yalis students and Elders as best I can. It is my hope that their stories and accounts may be helpful to researchers, curriculum developers, and teachers who are developing an awareness of the complex issues involved in teaching science in communities comprised of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

In 1982, when the initial data was collected for my research, the University of British Columbia Ethics Review Board required that the location of studies in Indigenous communities be anonymized for the protection of youthful participants and that the names of communities be given pseudonyms. Thus, the doctoral dissertation identified the location of the study as “Salmon Cove.” However, recent consultations with the community and most importantly the students participants (now adults), has made it possible to reveal that the research described in this chapter took place in Alert Bay (‘Yalis), BC, its real location. Additionally, words that were used by the researcher and by participants in 1982 to describe Indigenous peoples such as “Native Indian” or “status” and “non-status Indian” have been edited or deleted to reflect current terminology. In addition, identifying the location as ‘Yalis has enabled a richer and more accurate description of the traditional Indigenous culture, as well as the historical events that helped shape the students’ orientations towards the seashore. It is hoped this description is more in keeping with our contemporary and personal journeys of truth and reconciliation.

Many years ago, while walking along a sandy beach, I became fascinated with watching children play. Some drew pictures of mom, dad, and little brother; others drew pictures of eagles or fishing boats. Several children busily built intricate roadways, castles, or forts. A number of other children imagined themselves to be road-graders, dump trucks, or forklifts and made power sounds as they collected and shaped the sand and mud. The children would run up and down the beach making wonderful loops and dives with outstretched wings; imagining themselves to be graceful seagulls or jet planes. A few must have imagined themselves killer whales, seals, or salmon, for they ran with marvelous undulating movements, swimming upside down and jumping out of the water. One little boy imagined himself to be a thunderbird with eyes bulging and breathing thunder and lightning out of his head. When one really takes the time to view children’s play, one becomes aware of the use of metaphor as fundamental to human communication. This becoming of a graceful seagull, a soaring jet plane, or a magnificent thunderbird is a process whereby children understand their experiences through metaphor.

This chapter describes how language (and in particular metaphor) is an important source of evidence for understanding the way we think and act; and describes the metaphor interview in detail to reveal its subsumed techniques and its richness in illuminating the complexities of a child’s belief system. Next an outline of the four metaphor formats constructed for the analysis of the students’ orientations to the seashore, and briefly explores how the metaphor interviews take into account the linguistic and socio-cultural background of the child.

The research described in this chapter is part of a larger study in the general area of research on children’s thinking about seashore relationships (predator/prey, habitat/food changes, etc.)—research which supports the view that children’s prior beliefs and values need to be taken seriously, and incorporated into the instructional setting (Snively, 1986, 1990).

Chapter 4 describes how the metaphor interviews were used to identify the Grade 6 students’ orientations to the seashore, as well as the relationship between the students’ orientations and their social and cultural background. Chapter 5 describes the students’ beliefs about seashore relationships prior to instruction, how the teacher attempted to take into account the students preferred orientations during instruction, and the students’ beliefs about seashore relationships after instruction. In other words, the chapter sought to explore the question: Can instruction enable students with a preferred spiritual orientation to the seashore understand marine ecology concepts without replacing, in the sense of changing, the students’ preferred spiritual orientation? Finally, chapter 6 provides a description of the longitudinal study I conducted 19 years later—when I located and interviewed the same individuals, now adults to determine if their orientations, life experiences and aspirations had changed.

Background to the Study

Students bring to the classroom ideas based on prior experiences. These ideas or beliefs have an impact upon the ways in which they respond to and interpret lessons in science. Researchers have been able to identify and describe such intuitive views for a range of specific phenomena, and they have also established that such views can be remarkably persistent.

Typically, researchers in science education have addressed the notion of constructed meaning by analyzing students’ cognitive beliefs about a narrow set of concepts or topic area. Scant and insufficient attention has been given to the values that underlie children’s thinking about the world. Researchers try to distinguish among cognitive, affective, and psycho-motor domains, but in fact, they cannot be separated; nor can they authentically capture the perspectives of Indigenous students who understand humans in terms of a holistic amalgam of their intellectual, emotional, physical, and spiritual dimensions. One way of attempting to capture some of the complex interplay among these human dimensions is by constructing an orientation. In this research, “an orientation means a tendency for an individual to understand and experience the world through an interpretive framework, embodying a coherent set of beliefs and values” (Snively, 1986, p. 11). By looking for patterns in the students’ thinking towards the seashore I was able to identify five different dimensions or orientations: scientific, spiritual, utilitarian, aesthetic, and recreational.

The five different orientations share many characteristics with the concept of worldview. Cajete (2000) defines worldview as “a set of assumptions and beliefs that form the basis of a people’s comprehension of the world” (p. 62). A worldview provides the lens or filter from which an individual views the world. For example, Indigenous scholars propose that there is a shared worldview amongst Indigenous peoples in which humans are intrinsically connected to the natural world (Atleo, 2004; Battiste, 2000, 2002; Cajete, 2000; Kawagley, 1995; Little Bear, 2000; McGregor, 2004, 2005; Michell, 2007; Michell, et. al., 2008). While a worldview corresponds to the entire spectrum of the way an individual views the world, the typology of orientations (scientific, spiritual, aesthetic, utilitarian, recreational) is more narrowly defined and can be understood as a focused component of a more broadly defined worldview. Thus, a worldview is an all-encompassing concept that includes orientations.

Orientations are thought to be deeply rooted aspects of our conceptual system and not easily accessible with normal probing techniques such as pencil and paper tests or even conventional interview techniques. One of the ways of understanding these broad intellectual commitments is to look more carefully at the nature of metaphorical thinking in children.

Only in the last 30 to 40 years have metaphors been viewed as a fundamental aspect of the human communication process that affects the ways in which we perceive, think, and act. In their seminal work, Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) claimed that metaphors are pervasive in everyday life—“Our ordinary conceptual system in terms of which we both think and act is fundamentally metaphorical in nature” (p. 3). But our conceptual system is not something we are normally aware of. We simply think and act more or less automatically along certain lines. Just what these lines are is by no means obvious. “Since communication is based on the same conceptual system that we use in thinking and acting, language is an important source of evidence for what that system is like” (p. 3).

Lakoff and Johnson consider some cultural metaphors that are coherent with an up-down, hierarchical relationship. For example, in Eurocentric cultures, “more is better,” “bigger is better,” and “faster is better,” are values that are deeply imbedded. Not all cultures give the same priorities to such metaphors. There are cultures where balance and centrality play a much more important role than it does in Eurocentric cultures. There are cultures where passivity is valued more than activity. Lakoff and Johnson cite the Westernization of cultures throughout the world as partly a matter of introducing the “time is money” metaphor into those cultures. “Much of cultural change, [they postulate], arises from the introduction of new metaphorical concepts and the loss of old ones” (p. 145). But it is by no means an easy matter to change the metaphors we live by. Because each person’s view of “time” and “money” may be different, “the same metaphor that gives new meaning to one person’s experiences will not give new meaning to another” (p. 22).

In taking an experiential view of metaphor, Lakoff and Johnson insist that personal perception, feeling, and encounter form the real ground that supports understanding. They argue that metaphor is not a peripheral and merely stylistic feature, but a central feature of human thought. The work of Lakoff and Johnson has implications for classroom instruction and learning. It suggests that metaphor is an important source of evidence for identifying and analyzing students’ prior conceptions. Since metaphor is fundamental to the human communication process, language is an important source of evidence for analyzing what their natural conceptions are like.

Lakoff and Johnson suggest possible sources for students’ prior conceptions. The experiential basis of metaphor suggests that the students’ conceptions are products of their life experience, that is, their bodies, mental capacities, emotional and spiritual makeup, and the way they interact with the physical, social, and cultural environments. It suggests that science educators need to attend to themes that extend further than previously explored.

Over the past several years researchers have used metaphor interviews to look at students’ thinking in environmental and science education projects, for example, to look at effective environmental education professional development for teachers (Ross, 2003), early adolescent environmental involvement amongst 10 to 12 year old children from 66 countries (Blanchet-Cohen, 2008, 2010), and the perceptions and experiences of Indigenous students who are successful in senior secondary science (Tenning, 2010).

I agree with Lakoff and Johnson in their view that language involves “whole systems” of concepts rather than “individual words” or “individual concepts.” My concern for how children comprehend their own experiences at the seashore suggests that the students’ conceptions about the seashore emerge from their interactions with one another and with the world (both urban and natural environments), and must be understood in relation to interactional properties such as, sensory experiences, emotions, and culture.

Participants and Methodology

My study in 1982 (Snively, 1986, 1987, 1990) involved the collection and analysis, by metaphor and literal interviews, of students’ orientations and belief before and after instruction, as well as interviews six months later. The participants consisted of a class of 20 (N=20) Grade 6 students in ‘Yalis (Alert Bay). With the intent of protecting the privacy of the young participants, all students were assigned pseudonyms.

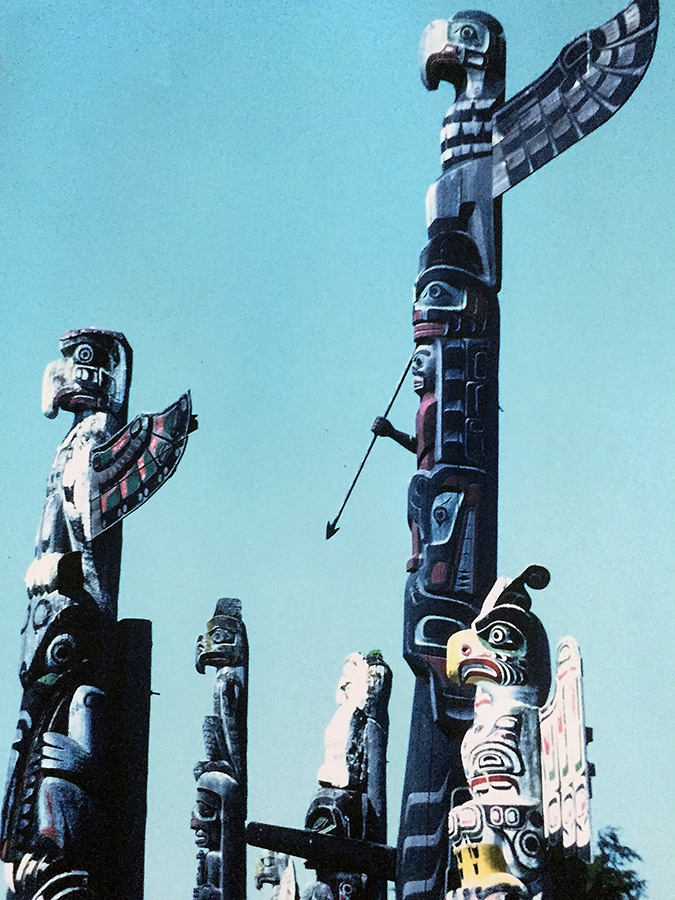

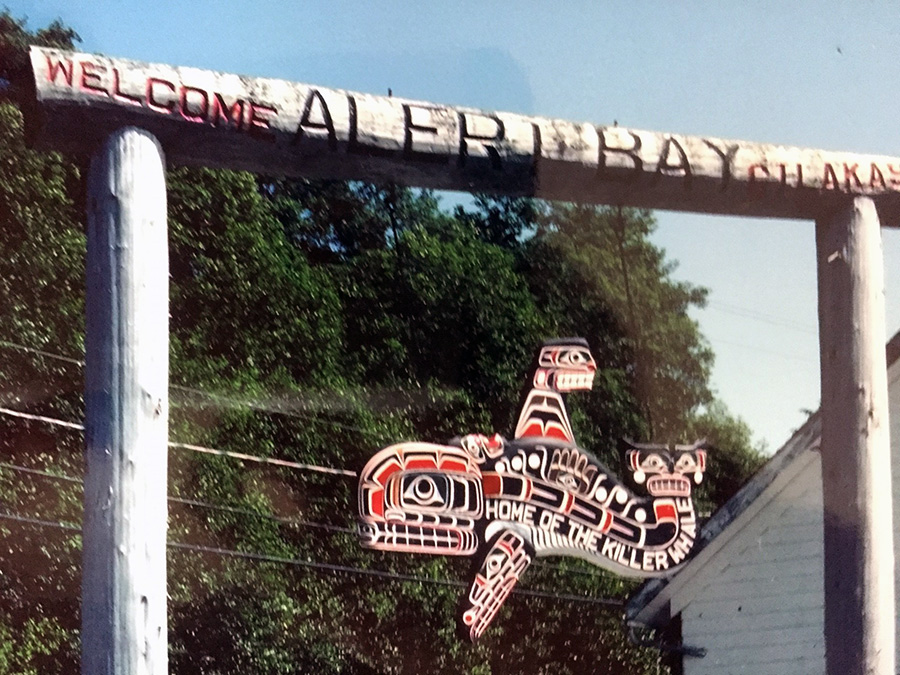

‘Yalis is located on Cormorant Island within the area known as the Broughton Archipelago, within the territory of the ‘Namgis First Nation, one of 16 remaining Kwak’wala speaking nations. The Nimpkish watershed is the largest on Vancouver Island. According to the legend of the river’s origin, it was the salmon runs that gave birth to the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. The First Nations community is located at one side of the island and a community largely of European extraction is located at the other. The Namgis cemetery, located in the center of the community, has some of the finest totem poles on the coast (Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.2).

At the time of this study, commercial fishing was the major source of income for both groups (Figure 4.3).

‘Yalis has had a long history of human habitation. It was used as a winter dwelling place by the Kwakwaka’wakw who realized that the unique shape of the bay offered protection against winter gales. The arrival of the Europeans and the realization of abundant fish stocks in the area brought with it the establishment of the fish saltery (processing plant) and canneries (Figure 4.4). Many Kwakwaka’wakw women worked in the canneries while the men worked on fishing boats catching mainly herring and salmon.

Gradually ‘Yalis became the centre of the whole area where schools, shipyard, seaplane dock, hotels, and stores sprang up. In 1982, the most imposing building in ‘Yalis was the largely abandoned three-story brick Indian Residential School that had been funded by the Canadian government and run by the Anglican Church (Figure 4.5).

Four churches were represented in ‘Yalis: Anglican, Catholic, House of Prayer, and Pentecostal. Despite a history of systematic colonial oppression, the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples continue to practice many traditional customs and ceremonies and have a strong presence with their ‘Namgis Band Office, ‘Namgis Traditional Big House, and U’mista Cultural Centre with its potlatch collection.

In 1978, I published a book entitled, Exploring the Seashore in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, and had conducted a number of workshops, talks and beach walks with several somewhat isolated communities and schools (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) along the BC Northwest coast. I was invited by the teachers and principal of the Alert Bay Elementary School to conduct a beach walk and a teaching workshop. This invitation provided a welcomed entry for conducting my research into students’ orientations towards the seashore. In addition to giving teacher workshops and beach walks, I gave seashore talks and walks open to the community: Elders, knowledge keepers, parents and interested residents—thus, at least to some extent, providing a two-way gift-giving relationship between myself and the ‘Yalis community.

The Alert Bay Elementary School was selected based on three criteria: (1) the presence of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, (2) the presence of a seagoing peoples and students born and raised in a community surrounded by the seashore, and (3) the willingness of the school, Elders and ‘Namgis Band to participate. It was expected that the presence of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students living in a coastal community would uncover a wide range of orientations towards the seashore and, also, would provide a rich mix of metaphor responses imbedded in sensory-based experiences on the one hand, and social and cultural experiences on the other. Four Kwakwaka’wakw cultural teachers offered dance and Kwak’wala language classes, and Kwakwaka’wakw history, legends, art and fishnet mending were a regular part of the curriculum. The Grade 6 teacher was new to ‘Yalis, having moved from the Prairie Provinces, and was in his second year of teaching.

The metaphor interviews worked effectively to enable the identification of the different orientations used by the students (scientific, spiritual, utilitarian, aesthetic, and recreation). Although all the students exhibited several orientations when describing the seashore, some used one orientation predominantly, and some showed a greater mix of orientations. Within the class, six students were selected for intensive study: the student with a preferred scientific orientation (Dan), the student with a preferred spiritual orientation (Luke), the student with a preferred utilitarian orientation (Jimmy), the student with a preferred aesthetic orientation (Mary), the student with a preferred recreational orientation (Anna), and a student with no preferred orientation (Sharon). Only a few students held beliefs that were consistent with accepted science ideas; most held beliefs that were quite different. For most students, there was a reasonably strong relationship between their orientations and the nature of their beliefs about specific seashore relationships. Luke, Jimmy, Dan and Mary are First Nations; Sharon is of European ancestry; and Anna moved to ‘Yalis from the Philippines.

The Use of Metaphor Interviews to Uncover Meaning

For several years, Beck (1978, 1982) explored the use of metaphor as an indicator of cultural values in an anthropological setting. Beck emphasized the values of people towards family relationships and the concept of ethnicity, paying less attention to the implications of values for specific beliefs and practices.

In attempting to use metaphor interviews, I had to solve three problems as the interviews had to be designed to: (a) explore the students’ orientations to the seashore, (b) explore the students’ beliefs about specific seashore relationships, and (c) be appropriate to the language development of young children.

During Phase I (from May 1980 through October 1981), I conducted a series of five small pilot studies with Grades 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 students in three different coastal communities in BC to sharpen the research questions and develop a research method. The problem was not one of extending or adapting some existing metaphor interview questions, but of developing a unique set of metaphor questions in which the analysis of the students’ orientations in an instructional setting was the central purpose.

In talking to various students and Elders in ‘Yalis, and by exploring the community and noting its special features, I was able to construct metaphor questions grounded in the physical and cultural backgrounds of the students. For example, the metaphors “pot-luck dinner” and “potlatch” were seen to be better utilitarian metaphors than the metaphors “dinner” or “supper.” The metaphor “cannery” was seen to be a better utilitarian metaphor than “factory,” since a fish cannery was an integral part of everyday life in ‘Yalis. The metaphors “totem pole” and “legend” were viewed as appropriate spiritual metaphors from a traditional Indigenous viewpoint, and the metaphor “church” was viewed as an appropriate metaphor for Christian spirituality, and so on.

The Metaphor Formats

In developing the metaphor interviews, the basic interview techniques described by Beck were followed, but ideas from Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) book, Metaphors We Live By, were incorporated to construct the interview questions. Following Lakoff and Johnson (1980), the very systematicity that allowed the students to comprehend one aspect of a concept in terms of another will necessarily hide other aspects of the concept. For example, in the “seashore is a playground” metaphor, the students were encouraged to focus on the recreational aspects of the seashore concept, and encouraged not to focus on aspects of the other orientations of the seashore. The interview questions were designed to highlight and hide a range of orientations towards the seashore: e.g., the image “painting” was selected to highlight an aesthetic orientation, a “community” to highlight a scientific orientation, a “church” to highlight a spiritual orientation, a “factory” to highlight a utilitarian orientation, and a “playground” to highlight a recreational orientation. For example, the first set of interviews asked each respondent to explore the following question:

| factory | church | painting |

| playground | community | gift |

The metaphor formats contained three additional types of questions that depended on metaphorical thinking. The second set of questions asked each respondent to explore fifteen different seashore animals, objects, events, and conditions. For example:

| vacuum cleaner | legend | potlatch |

| necklace | dance |

WHY?

OR

| jewel | factory | furnace |

| lamp | gift |

WHY?

Responses were intended to reveal the student’s reasoning towards selected animals, objects, events, and conditions at the seashore.

The third set of questions asked each student to explore twelve different imaginary questions. For example:

| raven | seagull | eagle |

In the fourth set of questions each respondent was asked to explore nine metaphoric dyads. Each dyad contained two types of questions that depended on metaphoric thinking. The metaphors were chosen to represent contrasting relationships: storyteller is to a story, character is to a story, or listener is to a story. The respondents were asked to decide which of the three pre-selected images was best suited to symbolize his or her own relationship to the seashore. For example:

| Storyteller is to a story | Character is to a story | Listener is to a story |

WHY?

In addition, the students were asked to indicate directionality. If the students’ relationship to the seashore was like a storyteller to a story, which element of the dyad would the respondents call the storyteller and which the story, and WHY? Some students found the metaphor questions in this interview too difficult to understand, possibly because of the double metaphor. Nonetheless, all of the students gave some explanation for their choices. Altogether, there were 124 possible metaphor responses (Snively, 1986).

They were also asked to generate their own metaphors for the seashore. One might think that metaphors generated by the students would be more revealing than those generated by the researcher, but this advantage was counter-balanced by the difficulty many students had thinking of metaphors for themselves.

Finally, at the conclusion of selected metaphor questions, students were asked to choose the metaphor response that best described how he or she viewed the seashore. It was hoped that by comparing the students’ preferred responses (their first, second, and third choice responses), and by noting their own metaphors for the seashore, that a distinction could be made between the students’ preferred orientations prior to instruction, and the effect of instruction on the students’ preferred orientations after instruction.

Identifying the Students’ Orientations

During Phase II (April, May, and June 1982), I collected interview data on all the students in a Grade 6 class in ‘Yalis. By looking for patterns in the students’ metaphor responses during the pilot studies, I identified five different orientations or dimensions in the students’ answers. The five orientations listed in the Table 4.1 below were those identified to be most useful in thinking about the responses students gave to my questions about the seashore. The phrases beside each orientation are not complete descriptions, but illustrate some of the broader ideas associated with the orientation:

A certain consistency in the reasons students gave could be seen to persist across their particular choices of metaphor. For example, “The seashore is a painting” metaphor frequently resulted in an aesthetic response. “The seashore is a factory” metaphor frequently results in a utilitarian response. On the other extreme, a certain consistency in the orientations students preferred could be seen to persist across their choices of metaphors. For example, the students with a preferred aesthetic orientation tended to stress the aesthetic aspects of the seashore regardless of the type of metaphor image selected and the students with a preferred utilitarian orientation tended to stress the utilitarian aspects of the seashore regardless of the type of metaphor image selected. Notice how three different students stressed different orientations for the metaphor, “The seashore is a gift”:

Some students, more than others, responded to a particular metaphor with a complex concept of the seashore. For example, notice how one student stressed a range of orientations for the gift metaphor:

Notice the obvious utilitarian aspects: “We use it.… The way the fishermen use it for fish.” There are recreational aspects as well: “And for fun too.” Also, notice the scientific or intellectual aspects: “People use it to learn about the animals.” Perhaps there is even a concern for conservation: “We’re supposed to use it properly.” Overall, there are subtle spiritual or moral aspects that may not be immediately obvious: “It was given to us to use. We’re supposed to use it properly. It’s like a special gift that was given to us to use.” Hence, a student’s response depends upon the complexity of thought the metaphor stimulates and upon other characteristics of the students’ thinking.

The metaphor “the seashore is a playground” used in the interviews, illustrates how an attempt was made to comprehend and represent the students’ orientations to the seashore. “Seashore” as a metaphor shows a focus of thinking formed from very different childhood experiences: growing up in a large, coastal urban centre such as Vancouver versus growing up in a small, isolated coastal community in British Columbia. Similarly, the word “playground” has very different kinds of experiential basis to a child whose only space for recreation is a city street or access to a large vacant lot, versus a purpose-built adventure playground, versus a child who has the freedom to explore a forested coastline. The concept of playground enters the child’s experience in many different ways and so gives rise to many different metaphor responses.

Metaphor interviews have a kind of ambiguity in the context of an experience. Students were asked to compare two terms: the term “seashore” of which something is being asserted, and the term “painting,” used metaphorically to form the basis of the comparison. Words have a range of meanings; some may have new or original meanings while others may have familiar meanings. The force of the metaphor depends on the respondent’s uncertainty as he or she waivers between the two meanings. Students’ responses should be viewed as the meaning, either consciously or unconsciously, that they give to the metaphor. Their emerging responses depend on the complexity of thought the metaphor stimulates and upon multiple characteristics of the student’s thought.

Two students’ interpretation of the term “playground” may be based on two different kinds of experiences:

Jimmy: The seashore is a playground. All the kids play on the beach. You find crabs, make stuff, teeter-totter, make masks from wood, make sticks to hold fish.

Dan: The seashore is a playground. I play at the beach a lot; catching animals, looking at them. I fly my kite

Some of the experiential basis for Jimmy’s metaphor response is obvious. For example, “All the kids play on the beach … teeter totter” is an obvious statement of the recreational aspects of the seashore. “You find crabs, make stuff, make sticks to hold fish” is an obvious statement of the utilitarian aspects of the seashore. Additional insights into Jimmy’s preferred utilitarian orientation came from the school staff:

While some of the experiential basis of Jimmy’s metaphor responses is obvious, some are not obvious. The statement “making masks from wood” is an implicit statement about the aesthetic or spiritual aspects of the seashore that is grounded in cultural experience. Stronger corroborating evidence comes from other examples of attaching spiritual significance to the seashore. For illustration, during the field study phase, the following data were collected from the Kwakwaka’wakw language and culture teachers:

Jimmy’s reference to “making masks from wood” is most likely a statement about the spiritual aspects of dancing in the big house and attending potlatches. This datum suggests that some metaphor responses can only be categorized and adequately represented when additional information concerning the student’s social and cultural background is taken into consideration.

There is another reason why it was important to categorize students’ metaphors in terms of entire domains of experience. Jimmy’s reference to “you find crabs” is very different from Dan’s reference to “catching animals and looking at them.” At first, the two statements appear similar in their experiential basis. However, important experiential differences become clearer when additional information is taken into consideration. For example, Jimmy makes numerous references to “finding crabs,” “catching fish,” “checking his crab traps,” “eating them,” and “making a lot of money.” By sharp contrast, Dan makes numerous references to “finding crabs,” “catching animals,” looking at them,” “learning about them from books,” and “letting them go.” Also, when asked to draw a picture of a crab at high tide and at low tide, Jimmy was the only student to draw an edible crab (Dungeness crab), while Dan drew the common purple shore crab. Jimmy’s reference to “finding crabs” is most likely a statement about the utilitarian aspects of an experience, while Dan’s reference to “catching animals and looking at them” is most likely a statement about the scientific aspects of an experience. The experiential basis of Dan’s preferred scientific orientation can be understood from interviews with him:

This is important, because many times clues to a student’s own understanding of a reference were found when it was related to similar references in the student’s entire set of metaphor responses, and to interviews with the students and with Elders and school officials in the community of ‘Yalis.

The Students’ Orientations Towards the Seashore Prior to Instruction

The metaphor interviews enabled me to identify the different orientations towards the seashore. While all the students exhibited several orientations when describing the seashore, some of them used one orientation predominantly, while others showed a greater mix of orientations. I focus in some detail on four students (Dan, Luke, Jimmy, and Mary). To begin, I describe the students’ preferred orientations only. At a later point I describe the entire set of orientations for the selected students.

DAN

Dan’s pre-instructional interviews pointed towards a preferred scientific orientation, as evidenced by the great proportion of responses reflecting an understanding of beach ecology. For example, he correctly identified numerous predator-prey relationships. For example:

A barnacle is a fisherman. It comes out and collects plankton from the water.

A starfish is a can opener. It can open clams, mussels, and many other shellfish.

A seagull is a robber. It steals food from little crows and peregrine babies.

Dan identified at least three different habitats—under rocks, in mud, in tidal pools:

Dan was one of the few students to express an awareness of the sun as the source of energy:

Several of Dan’s metaphor responses stressed a concern for the care and preservation of living things:

Compared to the other students, Dan expressed the greatest awareness of seashore relationships and, in addition, expressed an understanding of the seashore that was generally consistent with Western Science ideas.

LUKE

The results of Luke’s pre-instructional metaphor interviews pointed to a preferred spiritual orientation to the seashore, with numerous references reflecting the spiritual beliefs of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of ‘Yalis:

I would be a listener to a story. I would listen to what happened a long, long time ago, about the Killer Whale, the Thunderbird, the Raven. My Uncle would be the storyteller.

I would be a raven. If I were Gwa’wina I could soar and catch killer whales. Only ravens and thunderbirds can catch the killer whale. Raven played tricks on its cousins and brothers.

The tide is a song. When I go down to the beach, I sit there and listen to what it might be saying—maybe the spirit of my ancestors might be in the tide or the waves.

The tide is a legend. The wolves looked after the tide long before anyone was born.

The seashore is a legend. There’s a legend about this man who became wild and he went down to the beach every day and he ate mussels, clams, and abalone. One day one of his brothers went down to the beach. He saw his brother and went to tell his parents. They couldn’t catch him. But he was wild and he lived in a tree stump. He was wild and he could do things that the animals could do.

When asked what animal, object, or event at the seashore he would most like to be Luke replied:

Luke’s metaphor responses reflect the traditional stories of his people: stories about “The Wild Man in the Woods” who “could do things the animals could do,” and “Thunderbird” the “ruler of the sky,” and “Raven” who “played tricks on its cousins and brothers.” The spirits of Luke’s ancestors can be reborn and be in the tide or the waves. These spiritual stories portray an awareness of all animals as fellow creatures. Humans are not separated from nature, but are connected:

To some extent, it would appear that Luke is aware of the interconnectedness and the interrelationships of all life, “It’s the whole circle of life.” For Indigenous peoples, the journey towards harmony and balance begins with the sacred circle.

In addition, Luke is aware of pollution and the need for the care and preservation of the seashore:

In keeping with a traditional Indigenous spiritual orientation, there is a reciprocal relationship between humans and nature. Humans learn to live in harmony with the land and ocean; nurturing and protecting nature just as nature nurtures and protects them.

MARY

The results of Mary’s pre-instructional metaphor interviews pointed towards a preferred aesthetic orientation to the seashore. Several metaphor responses expressed an awareness of the beauty in nature:

The seashore is a painting. It looks like a painting an artist would paint.

A cobblestone is a totem pole. It has different shapes and colours. The way it looks is pretty.

I would be the curtain; the seashore could be the lace. It decorates. The beach decorates ‘Yalis up.

Several of Mary’s responses made connections to music and dance:

The tide is music. It sways. I like the way it sways. It looks like it’s dancing.

A seagull is a dance. The way it moves. It makes all that noise like music you dance to.

Interestingly, connections were made between Mary’s own physical beauty, social relationships, and making jewelry:

I would be a sunny day. Everybody would like me. I would be big and bright.

I would be a polished beach pebble. It’s shiny, not too big and beautiful.

The seashore is a jewel. Looking for shells on the beach, making things from the shells, like jewelry.

Rather than having an aesthetics orientation focused on the arts, Mary’s aesthetic orientation was more broadly focused on the “pretty” aspects of the seashore and included social relationships and concepts of personal “beauty” and “prettiness.”

JIMMY

The results of Jimmy’s pre-instructional metaphor interviews pointed towards a preferred utilitarian orientation to the seashore. Jimmy’s utilitarian orientation was almost wholly associated with commercial fishing:

I am the driver and the seashore is the car. I drive a seine boat and go fishing.

I would be a high tide. I would go check my fish net up the river for steelhead or sockeye or dogfish. I go up once a week and check my crab traps too.

When asked which animal, object or event Jimmy would most like to be, Jimmy said:

And he said:

A clam is a potlatch. When they have a potlatch feast, they make clam soup.

The seashore is a factory. It’s got lots of animals…. You can sell them to people for meat.

It is interesting to notice how Jimmy’s affinity with commercial fishing was so strong that he consistently turned even aesthetic images into utilitarian ones. For example:

In all these metaphor responses attention is paid to fishing, crabbing, clamming, eating, and to selling fish and making money.

ANNA

The results of Anna’s metaphor interviews pointed towards a preferred recreational orientation to the seashore, followed by an aesthetic and utilitarian orientation of considerably less proportion. For the sake of brevity, I will elaborate Anna’s recreational orientation only:

The seashore is a playground. To me it’s like playing. It’s like a big playground with little pools and sand. We play in sand, in big pools and on the nice smooth logs.

I would be a sunny day. People like the sun. It’s nice. You could go swimming, sailing, and surfing. You can get a suntan.

I would be a uniform and the seashore would be a hockey team…. A hockey player plays hockey, has a uniform and feels real close together…. I feel real close to the sea. Ever since I was old enough to go to the sea, I’ve been going there off and on: having fun, making sandcastles, playing on the beach, digging clams, playing Frisbee. We play tag down at the shallow end.

I would be the flower. The seashore would be the blackberry bush. Like as the flowers turn into fruit, I turn into the older generation, and I’m still going to the seashore when I die…. I’m thinking how I love the beach. It’s my favorite place to play.

In all these metaphor responses, notice the attention paid to swimming, sailing, sun tanning, surfing, and having picnics at the seashore.

Sets of Orientations

In studying the patterns of the students’ orientations, it is important to understand how all of the students relied on several orientations to describe the seashore. Where there were several orientations, there tended to be two or more orientations represented in each metaphor. These are exemplified in Dan’s and Luke’s sets of orientations.

DAN

In addition to a preferred scientific orientation to the seashore, Dan exhibited a spiritual orientation. Although Dan made no direct references to spirituality—traditional Indigenous legends or stories or any organized religion such as Christianity—it became clear that Dan’s metaphor responses express an individualistic spiritual orientation based on a deep reverence for nature. He made numerous references to the amount of time spent at the seashore:

I would be a uniform to a hockey team because I’m on the beach a lot of the time. A uniform is always on the team players.

I would be a leaf to a tree … and I could be bark to a tree because I’m there all the time.

Interestingly, numerous responses expressed a unique tendency to “indwell” or become part of nature:

I would be all of them: the flower, the fruit, the thorn to a blackberry bush. I’m always down at the seashore and I seem to be part of it … I always think about the seashore, even when I’m not there.

I would be the curtain and the seashore would be the stitches. The seashore would hold us all together. I wouldn’t be able to do everything without the seashore. It’s just part of me. It’s like my arms to me.

Several references were made to being the least in nature:

I couldn’t be the root to a tree. I’m not really the base of the seashore.

A character to a story. I see myself within the story rather than telling it. Occasionally you could be listening—sitting there watching … maybe you’re learning something…the little animals and communities within it. I think humans and myself would just be another minor player within the whole seashore story.… I’m trying to think of the words for how miniscule you are … just being a drop in the bucket. I mean all of the events that happen on the seashore—any one event is almost as insignificant as you are in the whole picture. ‘Cause you go down there one day and the bear rolls over a rock and a couple of crabs get squashed or something. And you say, oh well or Wow! But it happens every day. You’re just sort of a little fleeting moment in time.

Other responses stressed the inability of humans to control or to own the seashore:

There is a sense of unity with nature that transcends a physical presence. Dan’s relationship to the seashore can be seen as rooted in his view of himself as part of nature, not the most complex or important, but just another species sharing this world. And finally, in all these metaphor responses, it is important to notice the integration of emotion, feelings, intellectual reflection, and the humble servant or helper: “I’m sort of like part of the seashore” and “I always think about the seashore, even when I’m not there.”

Dan also used an aesthetic orientation towards the seashore. Several metaphor responses expressed an appreciation of the beauty in nature:

A starfish is a flower. It sort of looks like one, the shape and colour.… Some of them are pretty.

I’d mostly be the lace to a curtain…. The seashore decorates all my life and makes it nice.

I would be the killer whale. The way it looks. How it moves … easy … slow. How it can move fast. And its speed for catching fish and catching seals and sea lions.

A recreational orientation was also evident:

The seashore is a playground. I play at the beach a lot: catching animals, looking at them. I fly my kite.

The seashore is a gift because of the many things that live there … it’s nice to play by and enjoy.

I would be all of them: a door, a window, a roof to a house. They’re always there. I’m at the seashore a lot of the time. I’m playing, and I might go out in my boat.

Only three metaphor responses suggested a utilitarian response:

I could only be the deckhand to a fishing boat…. A deckhand’s there when its fishing time.

I could be a fishing boat. I could catch fish. I could catch cod and halibut.

A clam is a potlatch. You can eat it.

Clearly, the proportion of scientific responses indicate that Dan brought to his curricular experiences a preferred scientific orientation towards the seashore, although several orientations were evident, including spiritual, recreational, and aesthetic. A utilitarian orientation was almost lacking.

The Relationship between the Students’ Orientations and their Social and Cultural Background

To gain some idea of what it means for the students’ orientations to be grounded in their previous experiences, I explored the relationships between the students’ set of orientations and their physical, social, and cultural environments. Data included interviews with teachers, the school principal, culture teachers and Elders in ‘Yalis. For continuity, I continue the biographies of Dan and Luke. For comparison, I have provided a brief account of the social and cultural backgrounds of Jimmy and Mary.

DAN

As discussed earlier, Dan had a preferred scientific orientation to the seashore. To understand the basis of Dan’s preferred scientific orientation, data were gathered in an interview with the primary school teachers:

Further information was gathered in an interview with the principal:

Such sensory-imbedded experiences at the seashore would account, at least in part, for Dan’s keen awareness of the subtle aspects of seashore relationships. More data collected in the interviews with the teachers provide insights into Dan’s family and school backgrounds:

Last, I had been hearing stories about a unique salmon enhancement project in ‘Yalis. Since the project had been organized by Dan’s father, I asked Dan if he would give me a more detailed description. Dan seemed especially delighted to talk about the project, and eager to show off its independence from the government:

It was my dad and fifty guys. It had nothing to do with the government. Everybody’s going broke. The fishing isn’t good. Some people are losing their boats. The creeks are ruined for spawning because of the logging.

The flooding caused sand and gravel to wash away the salmon eggs. My dad got everyone to volunteer their time and money. One boat was anchored in the bay. Every boat that came in gave two fish per catch. We paid for a helicopter to fly eggs from a fish hatchery to the spawning grounds…. I was the only kid that helped. We cleaned up the creek ourselves…. I helped catch the fish and milk the eggs. We put in 100,000,000 eggs. We estimate about 3% will come back. Next year we plan to put in a hatchery right at the river. Raise the eggs till they get eyes. We did it ourselves rather than through the government because it was cheaper.

Those people from Vancouver shouldn’t log around the rivers. All those people fight over who’s going to log what. They want to log the Nimpkish Valley. Ruin the creeks for spawning so the salmon eggs wash away. Ruin everything. Everybody’s concerned. I can’t do anything right now, but when I get older I will.

Notice the utilitarian and Western scientific orientation: Dan uses modern conservation and management practices used by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada to complement old traditional ways of sustaining the salmon fishery. Modern enhancement practices are similar to traditional practices where knowledge keepers and Elders successfully governed their traditional fisheries for thousands of years. This is because the Kwakwaka’wakw (as with other tribes along the coast and in the interior of BC) followed strict fishing practices based on respect for the salmon. If streams were depleted, juvenile salmon (or herring or trout) were packed into bentwood boxes or cedar baskets, transported on foot or by canoe, and the stream or lake enhanced.

The metaphor interviews also showed that Dan had a significant aesthetic orientation to the seashore: “The seashore decorates my life and makes it nice.” The following from the school principal provides some understanding of the possible grounding of Dan’s aesthetic orientation:

Dan’s grandfather is First Nations from ‘Yalis who married a Finnish woman from Sointula. Dan’s father is a very successful fisherman. He fishes about four months a year. During the winter months there’s a lot of free time for arts and crafts, music and reading…. An enviable lifestyle.

The mother is a very talented artist who does mostly watercolour. She excels as a homemaker—needlecraft and jewelry work. Her watercolours and jewelry are sold in the art store. Dan’s dad is a craftsman, makes beautiful mandolins and guitars, as well as silver work.

Additional data were obtained from Dan:

Every Friday night ten or fifteen people come over. Mom plays the autoharp and dad plays the mandolin. I play saxophone, also guitar, mandolin, and ukulele. We sing a lot too.

I draw more than anything I’ve ever done: boats, lots of animals, cars, over and over again. Now I’m drawing scenery—a few boats together or a close up of one just ahead of the other.

Considering that Dan had a lot of free time, and that the arts were encouraged at home by both parents, it is not surprising that he exhibited aesthetic and recreational orientations to the seashore.

Recall that many of Dan’s metaphor responses express a spiritual orientation towards the seashore, even though no responses suggested a traditional Indigenous spirituality, or Christianity, or any other organized religious affiliation. To find possible reasons for the absence of direct references to Indigenous spiritual stories and legends or to organized religious beliefs (the Christian Church), I interviewed the school principal:

Although the family appears not to practice traditional Indigenous customs as interpreted by the school principal, it is interesting to compare their “appreciation ceremony” to the traditional practices of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples: the “Salmon Dance,” the “Prayer to the Salmon,” and the “First Salmon Ceremony.” In my conversations with Elders and community members it is important to understand that traditionally the Kwakwaka’wakw welcomed the first salmon by having a feast for at least four days. Musgam’dzi, (Kaleb Child), describes the first salmon ceremony:

Dances, song, ceremonies, and spiritual practices are a fundamental element of Kwakwaka’wakw worldviews even today. First salmon ceremonies are still carried out in meaningful ways to recognize and celebrate the critical importance of salmon. Our connections to the salmon resource are deeply rooted in our origin stories and our continuing cultural history, representing contexts of sustainability by making time through ceremony for initial runs of salmon upriver to spawn. This in many ways allows us to express gratitude, acknowledge our relationship to our salmon relatives, to welcome the salmon, to honour the salmon, to show profound respect, and to purposely allow a major portion of the salmon to return to their traditional territories and watersheds from which they were born (Musgam’dzi, Kaleb Child, personal communication, January 28, 2018).

Thus, the first salmon ceremony was a way to sustain the fishery for thousands of years.

Also, it is important to notice Dan’s emotional feelings and respect for the seashore: “I would be all of them—a door, a window, and a roof to a house…. I’m sort of like part of the seashore, even when I’m not there.” Although there are no responses that clearly reflect traditional Indigenous spiritual stories, there is an attachment and a sense of unity with nature. To say that there are no underlying spiritual structures would be failing to see the depth and complexity in Dan’s love for the seashore. Dan’s belief system is grounded in a highly spiritual effort to protect and secure the human connection with nature.

Only three of Dan’s metaphor responses reflect a utilitarian orientation towards the seashore: the seashore is a place where Dan can “fish for cod” and “halibut” and “eat small clams.” At first the surprisingly infrequent mention of the more utilitarian aspects of the seashore appears to contradict Dan’s love of commercial fishing. For example, when asked what he most wanted to be when he grows up, Dan replied:

To gain further insight into the possible reasons for this apparent contradiction, I sought additional data from the school principal:

This data suggests that the problems of catching a large number of fish and of meeting financial obligations are not immediately obvious in a home where the father is a “very successful fisherman” and a “good manager.” It is also interesting to note Dan’s second choice if he couldn’t be a fisherman when he grows up:

The data also suggests that Dan was more aware of the utilitarian aspects of the seashore than his metaphor responses seem to suggest. As Dan’s family lived a “relaxed” lifestyle and was financially stable, there was little need for Dan to worry about utilitarian matters. I inferred that Dan, as an adult, would likely express his relationship to the seashore in a more utilitarian and activist way: “I can’t do anything right now [the destruction of salmon habitat], but when I get older I will.” As a Grade 6 student, Dan simply didn’t demonstrate much use of the utilitarian orientation when describing his relationship to the seashore.

LUKE

Remember that Luke’s initial metaphor responses suggested a preferred spiritual orientation to the seashore, expressed by numerous references to the spiritual beliefs of the traditional Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of ‘Yalis. The following data collected in interviews with the culture teachers provide insight into Luke’s particular spiritual orientation:

Further information was gathered in an interview with the school principal:

And finally, upon returning to ‘Yalis six months later to complete the long-term interviews, stories were told about a potlatch that Luke’s Granny had given over the summer. Luke described the potlatch:

I danced two dances all by myself. It was the first time. I danced the Hamatsa, a dance about the return of the chief’s son. It’s the story of the “Wild Man in the Woods.” He was lost in the woods. The people tried to catch him, but he jumped over them. They made a cage for him.

We had a big potluck dinner. It was really good: baked salmon, barbecued salmon, clam chowder, homemade buns. Mmm! My Granny gave away pillows, laundry baskets, homemade clothes, homemade shawls, homemade cushions, homemade dolls. I saved up my money and had a potlatch at the same time. I gave out toys: necklaces, squirt guns, dolls, magnifying glasses, quarters, nickels, dimes, and key chains.

Luke’s involvement in the First Nations cultural program at school and the fact that traditional spiritual beliefs are encouraged at home by his Granny and his uncle help explain why Luke would understand and experience the seashore through the oral traditions of his people. This telling and retelling of the spiritual stories, and the watching and enacting of his ancestors’ encounters with supernatural beings would account, at least in part, for Luke’s preferred spiritual orientation to the seashore.

Recollect also, that Luke had an aesthetic orientation to the seashore. To provide some idea of the possible grounding of Luke’s particular aesthetic orientation, I include information that was gathered in interviews with Luke:

The fact that First Nations art is clearly encouraged at school, in the home by Luke’s Granny, and that Luke’s great uncle is a well-known Kwakwaka’wakw artist suggests why Luke demonstrated an aesthetic orientation to the seashore. In addition, Luke had both a utilitarian and a recreational orientation to the seashore based on traditional Kwakwaka’wakw experiences: attending potlatches, eating barbequed salmon, baked salmon, and clam chowder; and recalling traditional stories such as “the Wild Man of the Woods who came down to the beach every day and ate clams, mussels and abalone.”

The legends and ceremonial dances of the Kwakwaka’wakw involve the marine and freshwater animals that are common along the coast and in local rivers and streams. The stories portray the ocean as offering a seasonal abundance of food. Thus, there was also a strong relationship between Luke’s utilitarian orientation and his awareness of seashore phenomena. For example, Luke’s participation in gathering, preparing, and eating seafood contributed to a good awareness of seashore life:

What is important to this research is that Luke’s spiritual, utilitarian, and aesthetic orientations are important dimensions of the traditional way of life in ‘Yalis, and contributed to a general awareness of certain seashore plants, animals, and phenomena which he considered of significance: killer whales, eagles, ravens, salmon, clams, abalone, seaweeds, tides, and so forth. Additionally, Luke’s particular spiritual orientation allowed him to believe in the existence of supernatural animals or beings, such as the Thunderbird and the Wild Man of the Woods.

Luke’s spiritual orientation is also grounded in the Pentecostal Church whose doctrines are fundamental in character. The following data were collected in an informal conversation with Luke as I was driving him to his Granny’s house to get his science project. When we passed the ferry dock, Luke laughed and said:

Recall that Luke lives with his First Nations Granny who was described by the school principal as “very traditional,” but also attends the Pentecostal Church. Because the beliefs of the Pentecostal Church seem divorced from the spiritual beliefs of the traditional beliefs of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, the blending of the two might seem strange. But if one examines many of the stories of the two belief systems, one finds there are certain common characteristics. Look at the metaphors involved in the ceremonies, the masks, the dances, and the legends of the Kwakwaka’wakw, and the metaphors, parables, and miracles of the Bible. While no pre-instructional metaphor response illuminated Christian beliefs, which seems surprising given the above conversation, Luke’s belief system embodies an integration of spiritual ideas about humans, animals, and all of creation.

The Case of Mary: The Student with a Preferred Aesthetic Orientation

In this section, I will only describe the relationship between Mary’s preferred aesthetic orientation to the seashore, and her social and cultural background. To account for Mary’s preferred aesthetic orientation, the following information was gathered in an interview with the principal:

Interviews with the primary teacher provided the following insights:

This data provides insights into Mary’s usage of jewelry, clothing, hair, and home metaphors to describe seashore plants and animals in the metaphor responses, and later to describe seashore organisms during instruction.

And finally, an interview with Mary revealed the following:

This data, at least in part, may account for Mary’s preferred aesthetic orientation towards the seashore.

JIMMY

Recall that Jimmy’s initial metaphor responses strongly suggested a utilitarian orientation to the seashore that was almost wholly associated with commercial fishing. An interview with the school principal revealed the following:

Jimmy’s familiarity with and ability to function as a harvester was not disrespectful to marine life or the environment. He can feed his family and take care of the animals.

Comparatively few metaphor responses reflect a spiritual or aesthetic or recreational orientation to the seashore. This seemed surprising given Jimmy’s Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry and his prior experiences in ‘Yalis. For example, the following information was obtained from the school counselor:

In an effort to account for the near absence of spiritual and aesthetic orientations, the following information was gathered from the home school coordinator:

Although highly speculative, the above data provides additional explanation for the near absence of obviously spiritual and aesthetic orientations. It is likely that Jimmy had both a spiritual and an aesthetic orientation steeped in traditional Indigenous ways that were of considerably more weight, but he simply preferred not to put himself forward or to share certain aspects of his thinking with outsiders. All of the above data are required to give an account, at least in part, of the interactional properties of Jimmy’s orientations and beliefs about the seashore.

Coherence across Orientations

The data suggests a certain internal coherence across a student’s various orientations to the seashore, and a certain external coherence between a student’s various orientations and his or her physical, social, and cultural background.

External Coherence

To understand how orientations are grounded in connections with physical experience, I briefly compare and contrast the cases of Dan, Jimmy, and Anna. From discussions with the students, it became clear that: Dan interpreted the word “seashore” specifically as the inter-tidal region between the land and the sea; Jimmy frequently interpreted the word “seashore” more broadly as the offshore water and the open coast; while Anna focused partially on the seashore in ‘Yalis and partially on the seashore in her native Philippine Islands. The fact that these three students interpreted the word “seashore” as a different marine environment reverberated through the metaphorical connections each chose.

In the case of Dan, there was external coherence between his particular set of orientations and the type of seashore that exists in ‘Yalis. As such, Dan’s scientific orientation was coherent with a type of seashore that is home to a diversity of seashore seaweeds and animals. Dan’s particular recreational orientation is externally coherent with a picturesque harbor filled with fishing boats, beaches with gnarled trunks and twisted branches meeting the sea, and a continuous chain of spectacular white-capped mountains in the distance. Similarly, Dan’s low utilitarian orientation is generally consistent with a type of seashore that supports comparatively few preferred edible animals. ‘Yalis beaches are cobblestone set on hard rock, which support seafood such as seaweeds, chitons, limpets, and sea urchins (the latter three not commonly eaten today); but comparatively few seafood such as butter clams, geoduck clams, littleneck clams, oysters or Dungeness crabs which live on mixed sand, mud and gravel beaches.

In Jimmy’s case, there was a certain external coherence between his particular set of orientations, and the type of physical environment that exists along the BC coastline. Jimmy frequently interpreted the word “seashore” as the offshore waters and the open ocean, and his utilitarian orientation is externally coherent with a coastline that supports a great diversity of commercial fish (sockeye salmon, chum, herring, coho, halibut, cod, flounder, etc.), as well as the wide-ranging Dungeness crab, shrimp, etc. At the other extreme, Jimmy’s comparatively low recreational orientation is externally coherent with the type of lifestyle that frequently goes with commercial fishing in a very competitive fishery where losing one’s boat and source of livelihood is a constant threat. Jimmy’s comparatively low aesthetic orientation seems surprising given the aesthetic qualities of ‘Yalis and the presence of traditional First Nations art. Despite these inconsistencies, Jimmy’s orientations are externally coherent with the type of physical coastline generally.

Anna’s case, on the other hand, showed a certain external coherence between her particular set of orientations and the type of physical environment that exists in the Philippines. Anna’s preferred recreational orientation, which stressed swimming, sailing, surfing, playing Frisbee, picnicking, beach parties, and sun tanning, is coherent with long sandy beaches and hot tropical weather. The data suggests that Anna may have had a recreational orientation of considerably less weight had she more consistently interpreted the word “seashore” as meaning ‘Yalis beaches, which are cobblestone, frequently rainy and generally cold. It seems that the students’ orientations are grounded in systematic connections within their real and perceived physical environment.

Internal Coherence

Lastly, there was a general internal coherence among the various orientations shown by each student. In the case of Dan, for example, several of his orientations tended to point to his preferred scientific orientation to the seashore. For example, Dan’s preferred scientific orientation is internally consistent with a father role-model who taught Dan, at an early age, to observe closely, identify organisms from a library of books in the home and on the fishing boat, and to use conservation management to help solve the problem of rapidly dwindling fish stocks. His particular spiritual orientation, which stressed a unity with nature and an ability to indwell, complemented his scientific orientation. His particular aesthetic orientation, which stressed observing closely and drawing and painting seascapes and animals like a Lansdowne artist, was consistent with his scientific orientation. His particular recreational orientation, which stressed independent exploration at the seashore, catching animals, looking at them and letting them go, was consistent with his scientific orientation. Although few responses stressed a utilitarian orientation, his interest in commercial fishing and duck hunting was coherent with his interest in science.

It seems that each student’s orientations form a system of relationships grounded within his or her previous physical, social, and cultural experiences. Following Lakoff and Johnson (1980), I am proposing that the students’ orientations are products of their perceptual, mental, and emotional makeup—their interactions within their physical environment (seeing, hearing, touching, observing animals, rocks, sand, and the type of seashore), and their interactions with others in their culture (in terms of family, social, cultural, economic, religious, institutions). In other words, the kind of conceptual system the students have is a product of the way they interact with their physical, social, and cultural environments. For a more complete discussion of the internal and external coherence of the students’ orientations see Snively, (1986).

In the lives of Dan, Luke, Jimmy, and Mary we can see the struggles of growing up in a small Indigenous coastal fishing community during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Each had been influenced directly or indirectly by the beliefs and values of their family (parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles), the community, the big house, the Christian church, the lingering effects of the residential school, diminishing fish populations on the coast, and so forth. Each in his or her way had attempted to make sense of the world within the web of clashes between the Indigenous world and the Eurocentric world. Into this clash of beliefs and values, the students must also navigate through school science curriculum.

The question arises: How can teachers take into account the students’ preferred orientations during classroom instruction? Can teachers design instructional metaphors to enable students with different preferred orientations to understand basic ecology concepts? Can the instruction enable students, with a preferred spiritual orientation to the seashore, to understand marine ecology concepts without replacing, in the sense of changing, the students’ preferred spiritual orientation to a preferred scientific orientation? These are the issues we turn to in chapter 5.

REFERENCES

Atleo, E. R. (2004). Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth worldview. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Battiste, M. (2000). Maintaining Aboriginal identity, language, and culture in modern society. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 192-208). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Battiste, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: A literature review with recommendations. Ottawa, ON: National Working Group on Education and the Minister of Indian Affairs, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC).

Beck, B. (1978). The metaphor as a mediator between semantic and analogic modes of thought. Current Anthropology, 19(1), 83-97.

Beck, B. (1982). Root metaphor patterns. Semiotic Inquiry, 2, 86-97.

Blanchet-Cohen, N. (2008). Taking a stance: Child agency across the dimensions of early adolescents’ environmental involvement. Environmental Education Research, 14(3), 257-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802156496

Blanchet-Cohen, N. (2010). Rainbow Warriors: Environmental Agency of Early Adolescents. In B. Stevenson & J. Dillon (Eds.), Environmental Education: Learning, culture and agency (pp. 31-55). Rotterdam, NLD: Sense Publishers.

Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Kawagley, A. O. (1995). A Yupiaq worldview: A pathway to ecology and spirit. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Little Bear, L. (2000). Jagged worldviews colliding. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 77-85). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

McGregor, D. (2004). Traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable development: Towards coexistence. In M. Blaser, H. A. Feit, & G. McRae (Eds.), In the way of development: Indigenous peoples, life projects and globalization (pp. 72-91). New York, NY: Zed Books.

McGregor, D. (2005). Traditional ecological knowledge: An Anishnabe woman’s perspective. Atlantis, 29(2), 103-109. Retrieved from http://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/1057

Michell, H. (2007). Nihithewak Ithiniwak, Nihithewatisiwin and science education: An exploratory narrative study examining Indigenous-based science education in K-2 classrooms from the perspective of teachers in Woodlands Cree community contexts (Doctoral dissertation). University of Regina, Regina, SK.

Michell, H., Vizina, Y., Augustus, C., & Sawyer, J. (2008). Learning Indigenous science from place: Research study examining Indigenous-based science perspectives in Saskatchewan First Nations and Métis community contexts. Saskatoon, SK: Aboriginal Education Research Centre, University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved from http://iportal.usask.ca/docs/Learningindigenousscience.pdf

Ross, L. (2003). The search for effective environmental education professional development in the Colquitz River watershed stewardship project (Master’s thesis). University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

Snively, G. J. (1986). Sea of images: A study of the relationships amongst students’ orientations, beliefs, and science instruction (Doctoral dissertation). University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2429/27253

Snively, G. (1987). The metaphor interview and the analyses of conceptual change. In J.D. Novak (Chair), Proceedings conducted at the Second International Seminar of Misconceptions and Educational Strategies in Science and Mathematics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Snively, G. (1990). Traditional Native Indian beliefs, cultural values, and science instruction. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 17(1), 45-59.

Tenning, A. (2010). Metaphorical images of science: The perceptions and experiences of Aboriginal Students who are successful in senior secondary science (Master’s thesis). University of Victoria, Victoria, BC. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1828/2758