Chapter VII: Modern Ages: 19th and 20th Century Understandings of Interdisciplinarity

We describe the modern era in history consisting between the early to mid 1800’s to the present day. The emphasis will be less on the twenty-first century and more about the impact of interdisciplinarity on the nineteenth and twentieth century along with the growth of knowledge and epistemology in this time. What did the growth of knowledge look like in the nineteenth and twentieth century? One example could be the growth of industry with the Industrial Revolution taking place through the innovation of machinery producing more high-quality goods, in less time, with less resources on a scale never seen before. We see the work of capitalism take shape in places like England and the United States that significantly enhanced learning, life, and society in ways that have not been seen since the expansion of the Roman Empire. Although there were many positives, new issues also came into focus involving corruption, labor exploitation and the clear fractioning of an upper, middle, and lower-class system.

One way to thematically look at the Modern Era is to reference the film There Will Be Blood by Paul Thomas Anderson. We have the main character Daniel Plainview as the evil side of industrialization and capitalism taking advantage of people including his foil Eli Sunday; this is most notable during his ‘milkshake’ monologue, which he enjoys a perverse pleasure of sucking up money, resources, and power from the land1. Another view is that we have an individual who climbed out of a dark hole with a broken leg, painstakingly crawled on his back to earn a small fortune to build an oil well, eventually growing a company to become the oil titan of his time; all the while dealing with viperous corporate enemies, ‘family’, the harsh business of drilling for oil. Not to mention – Eli Sunday – the false prophet of hope. With the growth of the nineteenth and twentieth century, the interdisciplinary goal is to look at the era objectively and find the interdisciplinarity from topics, with differing opinions on the topics.

Some historians and academics look back on this time and see nothing but a ‘change for the worst’, referencing the rise of capitalism, continuance of colonialism, and the oppressive formation of a new world. Others have seen this era as a successful boom to overall standard of living, the growth of freedom through laws and institutions, more access to voting choice within a democracy, the complete eradication of slavery for the first time in thousands of years, and an advancement in science so expansive people in the Medieval Era would faint under their hand-drawn ploughs. The interdisciplinary aim is a competing narrative and a contextual argument – based on all sides to determine the eras interdisciplinarity as an advancement of learning, life and society.

As a preamble of sorts for the chapter, it is important to observe the state of the world during the nineteenth and twentieth century in the two biggest powers at the time: England and the United States of America. England during the nineteenth century was in the Victorian Era named after the reign of Queen Victoria which lasted from 1837-19012. Economically, industrial growth was expanding, politically Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone engaged in rhetorical battle for years, and the height of a return to romanticism was challenging the rational and pragmatic notions of past years during the Enlightenment3. Across the pond in the United States, expansion was happening at a steadfast rate. With the Louisiana Purchase (1803) followed by Texas Independence (1835) and Annexation of Texas (1845), this introduces the concept of what Robert Kagan describes as Manifest Destiny as the westward movement of people from the original colonies to new western states4. Kagan describes Manifest Destiny as an ideal of movement on two fronts during the age of the Civil War. The northern expansion was to spread the liberal ideals across the untamed land of the west, while the southern expansion was to spread and enhance their economic growth of slavery5. The north won the civil war of course and continued expansion, much to the dismay of Aboriginal tribes in places such as Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Utah, which ended violently. This would set the precedent of the ‘ideal of liberalism’ as the ‘ideal of Americanism’ to be used as a catalyst in the twentieth century rhetoric of politics, economics, and culture.

What these two countries have in common is that they used the nineteenth century to expand their growth with the resources they had available. Common themes emerge from these nations regarding their ideals entering the twentieth century. First, economic expansion; second, military expansion; third, increase in progress and happiness. One can argue that the colonialized expansion was a horrific example of both nations including England’s expansion in Africa and India6, and the United States wars with the Philippines and Spain7. A counter argument might be to see expansion not as a form of power, but an analysis to maintain liberal, economic, and military safety to open up new routes of trade and partnerships with other nations. These are valid considering the imperialistic nature of the countries led to deaths for naturalized citizens over resistance of growth and a change in national culture. However, this issue is more complex, given one can argue the imperialistic nature could help avoid deaths of despair with industrial, technological, educational, and scientific advancements. The objective of interdisciplinarity in this instance is to balance a nuanced approach to attempt an answer to a complex question such as the pros and cons of imperialism.

Was the U.S. wrong to engage with Spain? Or were they trying to stop the spread of tyrannical royal states from a feudal kinship, a staple of American values? Was the English resource hungry in South Africa? Or were the Boers (who were also settlers) making the claim on land that was not theirs to begin with? Would Texas still thrive under Spanish tyranny, or the many dueling tribes of the Alabama, Apache, Comanche, Chocktaw, and Wichita tribes? Or is the Republic of Texas the beneficiary of some of the most free and liberal laws towards advancement out of all the states? The unfortunate thing about history is that it already happened and cannot be reversed, however, hindsight does provide a reliable answer to these interdisciplinary questions, and in most cases comparing other moments in history, you may be surprised on how divisive the answers are.

Industrial Precedent

The industrial revolution was a massive economic, population, and societal boom with the transition from an agrarian economy, to a machine economy with mass production commonly associated with the growth of the textile industry8. The phrase revolution implies a circular change in thinking for the advancement of society, it also implies that a revolution could change into another revolution or divert to a pre-revolutionary sense. I would like to use the industrial precedent definition, given its advancement of society and the beneficial action is akin to a law of advancement. Some might disagree with this concept; however, it is through liberalized countries with an industrial precedent that allowed the growth of education for criticism.

The defense of the industrial precedent comes in the form of growth within learning, life, and society during this time. Advancements in travel, electricity and new products enter the market, in addition, new laws being passed related to labor such as the 1890 decision by the United States Congress to pass the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to outlaw monopolistic growth of companies9. Furthermore, the growth of education during the industrial revolution was expansive, especially the establishment of the public-school system in the United States, quickly becoming the world’s best education system10. The implications here are the growth outside of the economic and manufacturing sectors. The United States – through industrialization – became a leader for innovation, invention, and education that would rival the world, at least in the first part of the twentieth century.

The growth within industry suggested a correlation with a growth in higher education. The introduction of Land-Grant Colleges and Universities in the mid to late 1800’s saw schools such as Michigan State, Ohio State, Purdue University (in 1862); followed by Arkansas Pine Bluff, and Tennessee State (1892) introduced a rise in agricultural and technological education for educational equality towards a larger group in society11. The advancement of education during this time is relatable to a demand in the workforce for industry and would continue to grow for the future. This was done under a pragmatic and experiential paradigm, merging theory with practice in a true interdisciplinary way.

Although, there were many benefits to the industrial precedent, not all benefited from it in the beginning. Laborers were subject to long working hours, societal inequality between owners and workers, and hyper-competition saw many different attitudes critiquing this movement towards an advanced society. This reflected a concept in society as economically advanced, but shortcomings in many social areas. In the mid to late 1800’s, these shortcomings introduced criticisms that came from the tenets of a modern capitalist system.

Challenge to the Status Quo: Introduction to Marxism

With the capitalist machine growing, some challenged the notion asking: ‘how much longer could this possibly last?’ A challenge of sorts to the precedent that industrialization brought to all of us in the form of economic and social prosperity, or was it perceived prosperity? It was through the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that would challenge the status quo of capitalism through the theory of Marxism in The Communist Manifesto (c. 1848). Marxism or communism is an economic principle based on the redistribution of wealth and the removal of private property to public ownership. Marx and Engels base this concept on a theory of feudal exchange between oppressor and oppressed12 and they provide their communist ‘ten commandments’ when defining the relationship between proletariat and bourgeoise:

- “Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

- Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

- Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the Proletarians and Communists populace over the country.

- Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children’s factory labour in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production.”13

One of the most common discussions in academic circles is the ‘validation of the Marxist principle’. Contradictions do arise within the manifesto, such as the proletariat is oppressed by the bourgeoises but needs the bourgeoises to lift them out of proletariat status. Another glaring contradiction is the concept of heavy taxes levied through the use of centralization of communication and transport (i.e. economy) towards the state. This defeats the purpose behind taxation as Smith concluded with capitalism that taxation comes from a free-market to help society and to be used for the public good. Scientifically, heavy taxes with control and abolishment of many forms of work will produce low yield for taxes, this leads to a cascading of negative social, economic and political outcomes such as drought and economic hardship (Soviet Union), massive debt (North Korea), and troubling work conditions (China).

The glaring overall contradiction is the main thesis against a capitalist system, which was founded before the communist system. If we refer to Smith; he had a grasp on good social, political, and economic taxation methods to boost livelihood in the commonwealth, and to not be a burden on the public14. Using the capitalist definition of taxation, Smith outlines the concept of public works and institutions for the benefit of society:

“That the erection and maintenance of the public works which facilitate commerce of any country, such as good roads, bridges, navigable canals, harbours, etc. must require very different degrees of expense in the different periods of society, is evident without any proof.”15

As previously stated, capitalism is not a perfect measure, and a reframing in a modern sense needs to address consumption on a deeper level. However, Marxism does not uphold any accountability towards the purpose of redistribution, rather shadows capitalist principles in order to obtain taxation and redistribute it to the public in the form of equalization payments with no economic direction. In many ways, Marxism could not be formed without taking the theory from capitalism to run a model for an efficient society. Many have said that communism comes from the failures of capitalism, I would challenge and suggest that communism uses the methods of capitalism and fails through contradictions of external perceived ideology.

In the realm of interdisciplinary learning, one aspect introduced an interesting concept of how one sees the world. This has led to why the theory of communism and Marxism is common within educational circles (we will discuss this further in future chapters). Out of a text relating to economics, came a theory about learning that is quite palatable called critical-utopianism. Critical-utopianism reflects the goals and plans through government, economic, and social systems to achieve a better way of life for the public. Marx and Engels describe the critical utopian model as:

“They hold fast by the original views of their masters, in opposition to the progressive historical development of the proletariat. They, therefore, endeavour, and that consistently, to deaden the class struggle and to reconcile the class antagonisms. They still dream of experimental realisation of their social Utopias, of founding isolated “phalansteres”, of establishing “Home Colonies”, or setting up a “Little Icaria”– duodecimo editions of the New Jerusalem – and to realise all these castles in the air, they are compelled to appeal to the feelings and purses of the bourgeois.”16

One might understand the need to consistently move towards a utopian model, insofar creating a better world than what you left, regardless of the class distinction between proletariat and bourgeoisie. However, it only goes so far as a theory, as utopia cannot be obtained, but it works toward a better understanding of our social structure. This idea of utopianism was found to influence many shifts within the end of the nineteenth century influencing twentieth century thinkers. Relating this theory in the scientific form is enhancing the commonwealth of a capitalist state through the ending of child labor, public school systems, and the founding of workers unions17 which greatly benefited the growth of society during the industrial revolution.

The fractionation between Marxism the economic theory (classical), and Marxism the political theory (contemporary) is an important distinction on the path this theory produces. The economic theory holds some truth on the issues regarding consumption and equalization, although the utopian theories themselves are unobtainable in a practical world, they can be applied within a general liberalized framework or capitalism and produce a level of fairness for workers. The political theory is much more dangerous as it starts through a notion of collective understanding and eventually proliferates into a tyrannical oligarchy as seen in the USSR, North Korea, China, and more recently Belarus, as the anti-liberal notion of control is the key characteristic. The critical understanding of thinking leading towards societal, political, and economic changes reflects a thinking that challenges and goes beyond the status quo. Although not all criticism is relevant or applicable, the ability to present it is viable in a liberal society. However, with the ability to present critical ideas in society to challenge the status quo, it must be backed scientifically with logic and reason – otherwise, you end up in a dogmatic conceptualization of falsehoods common in the Dark Ages. The roots of interdisciplinary are to expand, yet at the same time be grounded within a truth of reason and logic to provide a clear guidance and avoid dogmatic ideals.

Two Wars and then Came Commercialism

When the world was on fire in the early and mid-twentieth century, it is always an interesting concept to understand learning, thinking, and epistemology during difficult and strange times. With industrialization continuously growing, the hunger for education became larger for a broader demographic. Malcolm Knowles outlined the beginning forms of learning came from the Greek concept of pedagogy which means child-leading – reflecting on the time during and after World War I, where educators experienced issues with the pedagogical model when teaching adults, as the expansion of knowledge up to this point saw the adult members of society wanting to expand their horizons, so too brought a cultural transformation. Innovation, population mobility, and job availability tailored with the pragmatic and broad scoping adult education called andragogy was born in the years between 1929 and 194818 19. Andragogy uses a form of practical and logical understanding relating the concepts of epistemology and relation to the outside world. This builds off the understanding of John Dewey and his basis of experiential learning, which grounds the learning of real-world practices and reflection on those practices20.

This methodology was ground-breaking in education, considering it took the enlightenment principles of logic and reason – and placed it within a practical understanding for how it can be used in the world. Interdisciplinarity is found through three scientific principles of andragogy listed after World War II in the 1950’s:

- Goal-oriented epistemology

- Activity-oriented epistemology

- Learning-oriented epistemology21

Interdisciplinarity is the focus of expanding knowledgeable realms outside of the traditional learning models. Ergo, the andragogy model uses the tools of enlightenment statutes manifested in the real-world implications of learning, life, and society which itself is a pure interdisciplinary process. That interdisciplinary connection in of itself led to the greatest epistemological reformation during the post-war boom in the mid twentieth century.

In the post-war era, economy and society saw a massive growth in commercialization, including the commercialization of education. This is outlined by Slaughter and Rhodes who reflect on the enhancement of privatization, commercialization, and competition in the area of academic medicine which created a “medical-industrial complex”22. This competition proliferated throughout society achieving objectives towards new and better science leading to beneficial enhancements to a healthy society. The inverse however, could be detrimental towards a narrow framework for achieving societal goals and the creation of a competition structure towards the safety and protection of the society and the production of it. In addition, competition came in the form of education with newer schools and newer pathways for individuals to get an education producing more professionals to benefit a capital society. However, access relied on schools to be economically sustainable, as in costs coming from students in the form of tuition allowed access for some, but created barriers for others.

Benefits and detriments can be found with an enhancement of commercialization such as unfortunate divides, especially in education. Neoliberal education has widened the gap between rich in poor not only at a community level, but at a national and multi-national level23. Another way of looking at commercialization within higher education is that privatized funds and federal sponsorships were beneficial to scientific and technological advancement; mirroring a concept that leads to an advancement of learning in society24 25. However, the access to that advancement is missing and could be detrimental towards not enhancing new and different views of knowledge. Interdisciplinarity can be found on both sides relating to the commercialization of higher education to advance learning, life, and society such as the commercialization can be a negative as it is a continuance of the economic inequities that are currently in place. However, expanding beyond inequities are beneficial towards a society as it introduces a concept of where science and advancement comes from, without commercialization and competition we would not be in the successful position we are currently in. It would be beneficial to weigh each proposition in the form of a pro-contra analysis to understand what commercialization did for the post-war world. You must weigh the society you live in now with the implications of changes that are presented with an ideology, placing yourself on the outside and understand the future implications of a decision.

The Challenge to Enlightenment Values: Postmodernism

The growth of science throughout the twentieth century saw the advancements in many fields including physics, biology, astronomy, and engineering. From Henry Ford and the advancement of the automobile, to the work of George Mueller with NASA and the space shuttle technology grew leaps and bounds in the early twentieth century. Knowledge and thinking about the advancement of a society was on the upward trend, embracing the epistemological connections that help us overcome obstacles and challenges. Questions arose however, as the 1960’s saw critical challenges to the path that knowledge and epistemology took regarding ethics and truths challenging the foundation of knowledge.

The challenge to science in this era was in many ways an attack on science, as too an attack on science means an attack on epistemological connections for the benefit of society, thus an attack on interdisciplinarity. We discussed the challenge to the status quo from a Marxist perspective at the height of the industrial revolution, which instituted minor changes towards a sense of collective utopianism for members of society, such as workers and unions. However, this new form was an attack on thought, logic, empiricism and the very forms of grounded interdisciplinary thinking that grew over time.

“We have described human reality from the standpoint of negating conduct and from the standpoint of the cogito. Following this lead we have discovered human reality is-for-itself. Is this all that it is? Without going outside our attitude of reflective description, we can encounter mode of consciousness which seem, even while themselves remaining strictly in for-itself, to point to a radically different type of ontological structure. This ontological structure is mine; it is in relation to myself as subject that I am concerned about myself, and yet this concern (for-myself) reveals to me a being which is my being without being-for-me.”26

These are the words of Jean-Paul Sarte in his 1943 work Being and Nothingness, which outlines his theoretical construct of critical and existential thought in relation to thinking. Sarte often challenged the scientific or enlightenment notion as oppressive and bourgeoise not only in action, but in thought. Sarte would also write:

“Ontology furnishes us two pieces of information which serve as the basis for metaphysics: first, that every process of a foundation of the self is a rupture in the identity-of-being of the in-itself, a withdrawal by being in relation to itself and the appearance of presence to self or consciousness…The second piece of information which metaphysics can draw from ontology is that the for-itself is effectively a perpetual project of founding itself qua being and a perpetual failure of this project.”27

What Sarte contextualizes here is how we are, or the way of ‘being’ is to be present in ourselves with the existential dread of our perceived construct as our only existence. The perpetual failure to obtain a true self – although vague – represents a thinking that would attempt to devolve rationalization into a form of ‘no rationality’, considering rationality is only consciousness. This would be the start of a continuing thread throughout the challenge of science within the twentieth century with the creation of postmodernism and the members of the Frankfurt School.

Postmodernism was, and continues to be the tool that challenges the enlightenment rationality and the constructs of a modern society. This theory inherently connects epistemology to the socially structured or ideologically conscious – with the guiding ethos of subjectivity as opposed to the enlightenment objectivity. In other words, the postmodernist observes the anti-foundationalist doctrine which place truth and knowledge outside of fundamental belief towards an inessential belief. This challenges the foundationalist principle of truth, one could say there is a truth much greater than human comprehension, that foundational truth does exist. Another could say that this foundational truth is only in your conscious, and has no bearing in truth except for yourself. In one way you can say the interdisciplinarity is present here in terms of the argument on the principle itself. We have grown through the expansion of the argument from church vs. science; to industry vs. labor; to the nature of truth in the span of 700-1000 years. In a way, you could say that the discussion on foundationalism and anti-foundationalism is an epistemological growth that is outwardly in trajectory coming from the augmented knowledge of the past in relation to the future. Although this only provides a framework, it does not provide an answer to the underlying question, which we are still grappling with today of what is truth?

The most significant scholarship of postmodernism came out of The Frankfurt School – most famously from Herbert Marcuse and Theodor Adorno following the anti-foundational doctrine of Hegelian and Marxist principles in relation to truth, society, justice, economics, and politics. Marcuse’s work in 1955: Eros and Civilizations, develops the understanding of truth in society through the Freudian ethos on the conceptualization of structures in society that influence us and have power over us28. Adorno offers a critique of nature in Against Epistemology: A Metacritique (c. 1955-1956). Adorno addresses the challenges with foundationalism and a destruction of epistemology through a scathing review on the Husserlian concept of epistemology. This work is presented through the challenge of universal truth. He signifies truth must always have divergence or nuance, which presents a contradictory challenge on the concept of universal truth29.

What both of these authors offer is a clear challenge on Enlightenment Values delineating the concept of truth and understanding. Marcuse discusses the domination and natural oppression of the human being:

“[T]he memory traces of the unity between freedom and necessity become submerged in the acceptance of the necessity of unfreedom; rational and rationalized, memory itself bows to the reality principle [which] sustains the organism to the external world…In contrast [the domination principle] is exercised by a particular group or individual in order to sustain and enhance itself in a privileged position…The various modes of domination (of man and nature) result in various forms of the reality principle.”30

“Civilization is still determined by its archaic heritage, and this heritage, so Freud asserts, includes ‘not only dispositions, but also ideational contents, memory traces of the experiences of former generations’…As psychology tears the ideological veil and traces the construction of personality, it is led to dissolve the individual: his autonomous personality appears as a frozen manifestation of the general repression of mankind.”31

Adorno outlines the concepts of experience in nature and that the oppression of natural science is a fallacy of truth:

“These categories are revealed less in the output and states-of-affairs of the factual performance of cognition which the theory demands of them – they are dubious in all epistemologies – than in the function that such concepts fulfill for the sake of the consistency and unanimity of the theory itself, particularly of the mastery of its contradictions.”32

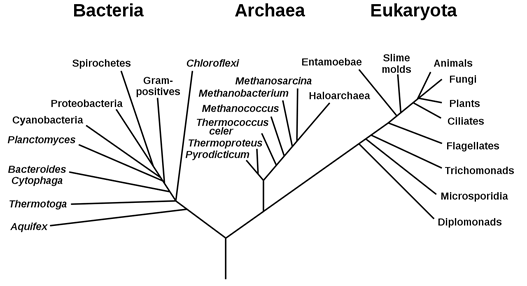

Further examination would conclude the anti-foundationalist principle of truth being divergent across many different spectrums and no natural foundation of truth. However, we now know using items such as the phylogenetic tree to make sense of human life that there is a set of anti-foundational principles of truth such as the existence of humans, animals, plants etc. much like how bacteria separate from archaea. However, it is the foundational principle in the split of the singular atom to create these anti-foundational principles, which thinkers like Marcuse and Adorno did not see at the time. The animal in the Eukaryota is the anti-foundational principle, the beginning of the phylogenic tree is the foundational principle.

Marcuse suggests the fight against the repressive nature of archaic history. However, given foundationalism that is unobtainable to a mere individual human, epistemology coming only out of experience, begs to ask the question, what creates the experience? Perhaps a natural foundational principle that governs us as something that is there, but we cannot explain or comprehend. We know the universe is large and can comprehend an age of 14 billion years estimated from astronomers33, but cannot comprehend the growth of the universe. Now is the incomprehensible fact that the universe rooted in the belief that there is no foundation? Or there is no inquiry on the growth of the universe? Or is it that the incomprehensible fact that the universe is justified, but above our knowledge stream as humans? I would believe the later solely on the fact that we have a clear foundational standard on measuring the universe through many years of science to observe a foundational principle, insofar as we are only able to comprehend with our perceived science and logic. Anti-foundationalist principles can not be standardized or measured as the postmodernist state concepts such as memory, privilege, ideologies, and dubiousness can be measured, but they cannot. It is the attempt in measurement of the foundation (i.e. astronomy and physics as an example) that lends the truth toward knowledge and epistemology.

Understanding History

History and record are important tools to comprehend and study our past, and so far, the history of interdisciplinarity has introduced us to the role of interdisciplinarity through our learning, life, and society. For this we can conclude that interdisciplinarity is inherent and logical to the human condition; perhaps going as far as saying it is a natural cognitive and biological trait. We can also conclude that throughout history logic, reason, and liberty prevail as fundamental towards interdisciplinary knowledge, and that interdisciplinarity is a natural tool we can use to enhance our abilities in finding knowledge for the betterment of learning, life, and society. Further inquiry into interdisciplinarity mirrors the interactions we have in the super-structures of our institutions we deal with daily: work, family, government, economy, friendships etc. This inquiry will help us center our individual selves toward the natural and inherent capabilities of interdisciplinarity to answer tough questions relating to truth and measuring the foundation of our knowledge.