Chapter VI: Renaissance and Enlightenment: The Golden Age of Interdisciplinarity

In a poem from one of the great writers during the Enlightenment Era, Alexander Pope outlines the role of man and underlines the ethos of the enlightenment:

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan,

The proper study of mankind is man. Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the stoic’s pride.

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast;

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reasoning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little, or too much:

Chaos of thought and passion, all confused;

Still by himself abused, or disabused;

Created half to rise, and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurl’d;

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!1

In this first stanza of the 1732 poem Of the Nature and, State of Man with Respect to Himself as an Individual or commonly called The Riddle of the World, Pope outlines the comedic fragility of the human being in this new era of knowledge. As Macfarlane opines, mankind was entering into a new world of scientific and epistemological revolution; and Pope, perhaps unknowingly, offered the most grounded predicament of human beings, that we are flawed2. This is the most significant contrast with knowledge during this time, the fact that the knowledge of a human being is vast and comprehensive through science and arts (as showed in the poem); yet at the same time, we are governed by laws, science, and the society that forms around us, like death which we are cursed with knowing. The Renaissance which came after centuries of religious, economic, and political turmoil at the hands of the Medieval dark ages attempts a redux or a return to classical ways of logical knowledge. These were profound as being a catalyst to a new way of knowledge in modern eras that followed.

What the Renaissance and Enlightenment Era did was turn back the clock on epistemological sense making, more succinctly, a return to the epistemology of the Greek Antiquity and Ancient Rome. Thanks to Johannes Gutenberg’s Printing Press (c. 1440-1452), the technical revolution of knowledge was now easily distributed to the masses3. In many ways the trivium and quadrivium went from the hallowed walls of the university, to the outside world where the academic dialogue spread across the land including the Latin language being used as a tool for epistemological expansion. Research by Reynolds and Wilson focus on work such as Plato’s Phaedrus, and Aristotle on making their way into the Western cannon starting in the Medieval period with other poetic works retained from Ancient Greece via the Byzantine Empire4. This presented a transformative concept towards knowledge and understanding, in a way, described as surfacing from the ocean for fresh air after the drowning suffocation of religious dogma in the Medieval Period.

One of the most important characteristics to Renaissance learning was the concept of humanism which influenced most aspects of Renaissance life, learning, and society. Humanism in the era as described by Reynolds and Wilson:

“[H]as been traced to the word umanista…to denote a teacher of the humanities, the stadia humanitatis, which by this time had crystalized as the study of grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy.”5

Humanism is an embrace of the interdisciplinary forms of learning from Chapter 5 – with the trivium and quadrivium and the growth of the scholastic institution. I would suggest the true description of interdisciplinary here relies on educators using humanistic concepts in the seven liberal disciplines. This creates knowledge in a form of apprenticeship outside of the ambiguity of ecclesiastical philosophy, although some scholars would opine that the humanism is indeed a way of seeing the world in a theoretical lens, the Renaissance era took philosophy and grew the art form in a divergent way through an informed or enlightened use of interdisciplinary thinking; pushing outwardly the boundaries of knowledge.

Polymaths and Renaissance Interdisciplinarity

In Europe, after the Middle Ages many nation states went through reforms, none bigger than Italy who were on the forefront of the Renaissance Era. Art and literature were at the head of the Italian Renaissance using the forms of humanism to create some of the most influential pieces in human history. One of the most influential authors that ushered in the Italian Renaissance was Durante di Alighiero degli Aligheri, or as he is referred to in common parlance, Dante. His famous work the Divine Comedy (c. 1320), is considered one of the most famous works of poetry of the Middle Ages and influential to the Italian Renaissance movement influencing a generation of knowledge, literation and art forms6 which led to the rise of the polymaths, most famously Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. The polymath is key to understanding interdisciplinarity, as interdisciplinary thinking and interdisciplinary nature is the Renaissance definition for a universal or learned person in a variety of different subjects. It was architect Leon Battista Alberti (c. 1404-1472) that stated a polymath or a Renaissance Man “can do all things if he will”7.

The concept of the polymath in the Renaissance era has been regarded as giftedness, especially with the relevance of da Vinci and Michelangelo. However, one might look at the nature of interdisciplinarity and wonder if all humans, in a frame of humanistic thinking, are different gradations of polymaths? Robert A. Heinlein sees this as a need for humans to be polymathic in a contemporary framework through his writings on the competent man:

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, coon a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”8

Aside from the sense of classical masculinity, or what I would like to call ‘ubermasculinus’; there is a sense that if you are a human, man or woman, you may not know how to butcher a hog or cook dinner, but understand that eating is about surviving. Perhaps someone with a weak stomach does not have the ability to set a bone, but should have the knowledge to be able to transfer the injured to a hospital to get the help they need. Although Heinlein’s comedic outlook could be far from any one person, the theory behind it is true, and that competency comes from the knowledge to make connections from certain situations that are a part of life such as love, living, eating, labor, and education. The main thesis of Renaissance Interdisciplinarity is that the polymath is not an expert in every concept around, but is competent to do these things or at the very least, understand their meaning to learning, life, and society.

One of the greatest scientists of the modern era Erwin Schrödinger attempted to connect the concepts of affine connections and differential geometry with a Lagrangian method was regarded as a “heroic attempt to attain the great unity of physical laws by way of geometrizing classical fields”9. The attempt to be a polymath is the ability to expand knowledge outside of classical realms and try something different. Much like Schrödinger, the polymath is willing to obtain knowledge in their specific field and expand their knowledge into other fields, the interdisciplinarity comes from the polymath’s ability to use their expertise to transcend their field into another field. The Renaissance and the Enlightenment produced this transcendent concept of knowledge outside of the social and institutional boundaries to make society and institutions better for it.

From Renaissance to Enlightenment: The Golden Age of Interdisciplinarity

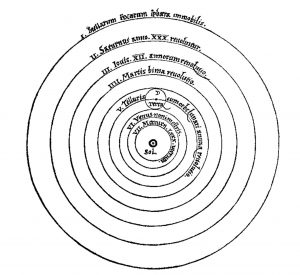

Remnants of the narrow and strict Medieval religious doctrines battled with one profession, perhaps more than any other: astronomers. There is a host of literature outlining the battle between priests and astronomers and no other astronomer felt this challenge than the Polish mathematician: Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543). Copernicus is widely known for the heliocentric model, which places the sun at the center of the known universe, rather than the Earth which was previously understood. Although this came many years after a theory was introduced by Aristarchus of Samos10, Copernicus is regarded as expanding and perfecting the model leading to a new age of scientific revolution. In his work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium or On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres (c. 1543) Copernicus outlines the now scientifically credible concept of the Sun in the middle of our solar system. However, at the time these were controversial ideals contradicting Ptolemy’s and the churches geocentric model of the universe. He outlines the spherical shape of the planets, the movement of the planets around the sun and the sphere of stars that make up the universe11. It was in this work he graphs and illustrates the solar system with the explanation:

“Therefore if the first law is still safe – for no one will bring forward a better one than that the magnitude of the orbital circles should be measured by the magnitude of time – then the order of the spheres will follow in this way – beginning with the highest: the first and highest of all sphere of the fixed stars, which comprehends itself to all things, and is accordingly immovable”12

Although, as we now know more about the universe, that the stars are not immovable, actually they follow the same laws as our star (i.e. The Sun). Copernicus was way ahead of his time regarding knowledge about the solar system and the universe. Even with vicious challenges from the church such as Philipp Melanchthon and Julius Caesar Scaliger who suggested that “[Copernicus’] writings should be expunged or their authors whipped”13. This work was instrumental to ushering in the Enlightenment thinkers and the scientific revolution.

The Enlightenment Era is considered one of the most important eras in the history of epistemology and knowledge; given it was the catalyst that moved human history from the tumultuous era of 14th century into prosperous 20th century. The impact on the growth of society was key as the Enlightenment saw mass-reformation in epistemology, society, economy, philosophy, and science through an intellectual movement predominantly in Europe14. Some look deeper to what was at the center of this intellectual movement and certain factors that related to the advancement. Cohen outlines the work of Claude Bernhard with this understanding:

“In this context Bernhard seems to have envisaged two separate processes. One was the large-scale dramatic revolution, the introduction of the experimental method…The second was ‘science in evolution’, primarily an incremental process having two aspects: using knowledge acquired already…and attaining new knowledge”15.

Stephen Hicks, a Canadian-American philosopher, outlines three names from the Enlightenment Era that were key thinkers to the web of logic, reason, progress and the ultimate pursuit of happiness16. The names he mentions are Francis Bacon, René Descartes, and John Locke. I would go one step further and add David Hume and consider his work on empirical philosophies a cornerstone to Enlightenment thinking.

The interdisciplinarity of enlightenment comes from what enlightenment stands for, a new and bright view on the world. These are commonly referred to as the Enlightenment Values and consist of: Reason, Logic, Liberty, Progress, and Toleration. Reason and logic outline a rationalistic base for all learning, freedom to pursue any type of learning especially the removal from institutional roadblocks with science were also important values. Progress comes from the continual advancement of knowledge, and toleration from maintaining the forms of humanism and natural law. What these authors provide is a clear augmentation of these values in their work which create a logical and rational base for knowledge that we continue to use to this day, especially in sciences.

Francis Bacon, the First Viscount of St. Alban (1561-1626) is known as the father of empiricism, the scientific method, and one of the most influential members of Enlightenment Era scientific revolution. It was in 1605 where Bacon formulated his ideas for the Baconian Method for inductive reasoning in The Advancement of Learning, this where life can be learned, thus learning can be obtained and advanced through civil history, ecclesiastical history, mathematics, epistemology, rhetoric, and moral culture17. René Descartes (1596-1650) is known as a great interdisciplinarian through his contributions in the area of philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy. The French national is regarded as the father of modern philosophy. Descartes is most famous for his position on logical philosophy with his famous quote “I think, hence I am”18, and provides the foundation for logic and reason tied to the human and only the human through interdisciplinary knowledge. John Locke (1632-1704) is the English philosopher and political scientist who is seen as one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers. He is regarded as the father of classical liberalism which have cross-disciplinary facets including political science, ethics, and educational theory. Lastly, David Hume (1711-1776) is the Enlightenment influencer from the highlands of Scotland. Known for his work on empiricism, he is regarded as a philosopher, historian, and economist. Hicks has referred to Hume in a minor instance to attributing a move away from the concepts of Enlightenment to a doctrine of multiple truths19; however, I would suggest that Humian concept of experience actually lent to advancement of empirical enlightenment than many philosophers have proposed in the past .

What these authors have in common is a shared understanding of epistemology and truth regarding knowledge. This itself, considering the time can be outlined as empirical given the shared beliefs on knowledge between many of the thinkers. There were criticisms from authors, notably Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Fredrich Heinrich Jacobi, and Johann Gottlieb Fichte which came out as Post-Kantianismc Idealism or German Idealism20. This would eventually set the stage between Foundationalist and Anti-Foundationalist doctrines which are present to this day in epistemology. However, idealism considers the subjective notion of how things are seen to us and how things are perceived, and truth can only come from experience. What enlightenment thinkers attempt is to cut through the subjective murkiness regarding ethics to create a foundational knowledge that governs all the idealism that is found. Essentially, if truth comes from experience, what creates experience?

These authors attempted to find the foundational principles that govern experience within the universe. This was done through challenging the disciplinary field of ethics and connection of different knowledge realms using interdisciplinarity. Bacon starts through the interconnecting nature of thinking under his rule of natural epistemology and logic:

“I take it those things are to be held possible which may be done by some person, though not by every one; and which may be done by many, though not by any one; and which may be done in the succession of ages, though not within the hourglass of one man’s life; and which may be done by public designation, though not by private endeavour.”21

Descartes in his Discourse on Methods (c. 1637) talks about his educational training and the critical views that come from his misguided teaching:

“But as soon as I finished the entire course of study, at the close of which is customary to be admitted into the order of the learned, I completely changed my opinion. For I found myself in so many doubts and errors, that I was convinced I had advanced no farther in all my attempts of learning, than the discovery at every turn of my own ignorance.”22

Locke in The Two Treatise of Government (c. 1681) outlines the need for freedom and autonomy for humans against tyranny toward natural law; and Some Thoughts Concerning Education (c. 1693) outlines the need for reasoning with a child to expand their competency in learning:

“To understand political power aright, and derive it from its original, we must consider what estate all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of Nature, without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man.”23

“They understand it as early as they do language; and, if I misobserve not, they love to be treated as rational creatures, sooner than as imagin’d. ‘Tis a pride should be cherish’d in them, and, as much as can be, made the greatest instrument to turn them by. But when I talk of reasoning, I do not intend any other but such as is suited to the child’s capacity and apprehension. No body can think a boy of three or seven years old should be argu’d with as a grown man. Long discourses, and philosophical reasoning, at best, amaze and confound, but do not instruct children. When I say, therefore, that they must be treated as rational creatures, I mean that you should make them sensible, by the mildness of your carriage, and the composure even in your correction of them, that what you do is reasonable in you, and useful and necessary for them.”24

Hume uses experience-relating-to-truth found in his work Of the Standard of Taste (c. 1757). The lesson of interdisciplinarity comes in the form of experience through experimentation leading to advancement in science. Inside this work, Hume references the literary work of Don Quixote to describe the difference of taste, where two men drink a bottle of wine, one senses a taste of leather, the other senses a taste of metal, only to find that at the bottom of the wine glass is a key with a leather tie attached25. Two different tastes, but through experimentation they find that both theories were correct and can be regarded as empirical and rational. With interdisciplinarity the ability of using experimental design and empiricism together can develop answers to complex issues augmenting two theories to make one. Innate characteristics of interdisciplinarity follow a methodological approach from Bacon; a natural contrarian or critical view from Descartes; an autonomous, free, and rational objective as outlined in Locke; and an experimental justification for finding expanded truth in Hume.

What do these authors attempt with interdisciplinarity regarding foundational truth in relation to Enlightenment Values? Well first is that learning must be free, and freedom cannot be taught, rather is inherited through our understanding as humans. This goes beyond the idealism principle towards a cognitive notion of interdisciplinarity and our innate ability to pursue knowledge – allowing for the freedom to obtain knowledge. Studies from Peter Curruthers and Allen Repko suggest the ability for creative and technological innovation dating back 40,000 years ago from species over 100,000 years old26, leading to the concept of established communication and cognitive constructs creating a sense of cognitive interdisciplinarity27. This connects the concepts of cognitive and neuro-networks working in an interdisciplinary way to create knowledge for humans, essentially lending evidence to the natural epistemology model of accepting natural law and foundational governance. Natural epistemology and logic within the laws of nature that supersede any human, govern our ability to learn and to have idyllic experiences.

In Practice: Economics, Science, and Social Elevation

Enlightenment Values in practice created some of the greatest advancements at the tail end of the Enlightenment Era. Economics came in the form of capitalism which brought a collective enhancement succeeding mercantilism – boosting trade and economic growth for states. Science grew from Antoine Lavoisier and Edward Jenner from 1789 and 1796 respectively, as Lavoisier created the initial Periodic Table and Edward Jenner’s contribution was the creation of the smallpox vaccine28. Another notable figure was Sir Issac Newton and his amazing advancements in mathematics, physics, and astronomy through formulation of Newtonian Physics and mathematical descriptions on the foundational concept of gravity29. This all culminated in a social elevation unlike the world has ever seen. In comparison to the Medieval world, the adults and children far exceeded in social progress and happiness.

In the modern era, criticisms of capitalism are presented, some acceptable, but most move away from the original concepts of capitalism as a general theory. Capitalism itself has an interdisciplinary framework through Adam Smith who sought to challenge past systems such as agrarian capitalism and mercantilism to create a new economic foundation based on liberty for trade, commerce, taxation, wages, labor, education, and society30. Smith outlines the theory relating to the systems of a political economy:

“Political economy, considered as a branch of science of a statesman or legislator, proposes two distinct objects; first, to provide a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, of more properly to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and secondly, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for public services. It proposes to enrich both the people and the sovereign.”31

Smith not only outlines the economic system of capitalism, but the political and social system of capitalism for the benefit of society, insofar connecting the ideas of a political economy focused on autonomous capital for the betterment of humans. Some opponents of capitalism might question any benefits, however, Smith does provide a concept of taxation to help society and the commonwealth which relates to a social contract in a relationship between citizen, state, and society. The interdisciplinarity framework from the Enlightenment of capitalism was to provide a sense of enrichment not only for an economy through systems of growing cities and the Industrial Revolution, but for a political and social life being a tool for systems that expand beyond the economic system.

It was in this economic system where science grew leaps and bounds in the goal of advancing learning, life, and society. This came about through the growth in social and economic systems for the people in society. It was the French that rounded the work on scientific advancement through new forms of economic salary for discovery and research32. This had led to a growth in the advancement of medicine in institutions through the growth in society. Institutions were able to provide funds and resources to professional workplaces such as hospitals and medical laboratories33 and compliment more people for health and wellness. These concepts would be paramount as the world moved steadfast in the modern era.

Interdisciplinarity is the Catalyst

The importance that interdisciplinarity played during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment era creates the connection between humans and their ability to make knowledgeable connections to create complex systems for the overall good. In summation, the prevailing outcomes from the Renaissance and Enlightenment Era produced massive benefits for learning, life and society in many ways including politics, economics, medicine, personal freedom, wealth, health, and progression.

At this point, it may be prudent to look at the Renaissance and Enlightenment as a framework for human growth and understanding. Although, many issues arose after the Enlightenment and into the modern era, the re-growth of interdisciplinarity meant the re-growth and practical expansion of knowledge to challenge issues. In many ways, to return to interdisciplinarity is to return to a natural sense of epistemology for the greater good for ourselves and society. It is important to look at the Renaissance Era and the Enlightenment with an appreciation of the current world we live in, I personally tend to stay away from “what-aboutisms” but one might consider, what would happen if the Medieval concepts from 500-1400 would have continued into a modern day society, what would our world look like and what would we be as a human race? I think about this questions often; with no growth in science, heightened feudalism with tyrant kings and queens owning lands, and the common human used as chattel; questions and implications like this should be considered as we dive into a new age in future chapters, also to outline some critiques and criticisms to the proliferation of modern systems.