Chapter V: Medieval Age: A Dark Age for Interdisciplinarity

Of the moments during the Roman reign that were most significant, what comes to mind? The rise of Julius Ceasar as dictator? The burning of Rome? Hadrian’s Wall in North Britannica? Perhaps the death of Marcus Aurelius as some historians claim was the end of the Roman Empire. Perhaps the most significant event that relates to the Medieval or Middle Age, happens to be the time of 30-33 AD when a carpenter with the word of God was crucified in Judea by the Roman Legion. This event influenced and mobilized the emperor Constantine, notably his wife Empress Helen to travel to the Holy Land and retrieve what Christians call the True Cross1.

Why this is significant is that it sets the foundation of Christianity in the Roman world and eventually influencing social, political, and economical factors in Europe during the Middle Ages after the fall of the Roman dynasty. However, this was considered a dark age in human history due to social strife through the dogmatic violence; economic hardships; degradation of health due to plague; and the high propensity of uneducated masses. Although this was the time when the concept of university came into form; the interdisciplinarity through learning, life and society was lost or at the very least hidden given the tumultuous ideals and societal factors of the time. Throughout this chapter, I will attempt to look at the Medieval period discussing areas pertinent to England, Italy, and other locales to find an interdisciplinary glimmer. Also, to provide a look into some other areas that have been commonly lost through general historical discourse. The question of pursuit in this chapter is: were the Middle Ages a truly dark time for interdisciplinarity?

Society within the Medieval period is commonly described as a never-ending tale of gloom and despair. One of the most common events had to do with the pestilence of the Black Death or the Bubonic Plague which claimed the lives of, by some estimates, close to 200 million people2 from the years 1346 to 1353. Another had to do with the stratified life based on feudalism and religion that dominated society during this era. Medieval society through this social structure was a clear fractionation based on class with royalty, lords, papacy, knighthood, and serfdom. Although stratified levels form in any natural setting, this displayed a crippling dominance over the serfs who relied on the process of fiefdom, which renowned French historian Marc Bloch suggests is the object of value or an exchange for gifts from the higher classes leading to complete servitude from the lower classes3. With this stratification, the growth of knowledge was stagnant especially in relation to the Bubonic Plague, where the mixing of non-advanced forms of medicine and religious doctrine were causing more harm than good. From blaming the air, to quartering a snake and rubbing it all over the infected parts of the body. This was a method as the snake was to draw out the devilish evil of the plague4, and as one can imagine, the symptoms of the pestilence were just as bad as the mitigation response from humans.

It is clear that the challenges with knowledge coming from religious dogma were detrimental considering the death toll of the plague on the population. As most health crises go, this is also trickled down to the learning, life, and society that people were a part of during this time, like the economy which took a massive hit given there were no competent, healthy, and available workers.

Religious Dominance: England, France, and Italy

Not only were Catholic and Christian priests’ spiritual leaders within Medieval society, they also had massive political influence given the tenets of feudalism lifted them up to a higher social standing. Within the realm of interdisciplinarity, the Medieval era produced – in a practical sense – a quasi-interdisciplinary creation and expansion in religion. However, to call the expansion a natural form of interdisciplinary movement through learning, life, and society is a flawed characterization as one might examine the proliferation of religion during the Middle Ages especially in the countries of England, France, and Italy as a troubling impact of fear and subservience.

In England during the middle ages most scholars discuss the movement and growth of Christianity through the British Iles; on the other hand, an interdisciplinary concept of religion in relation to stratified class. Carl Watkins suggests the dichotomy between elite and folkloric religion is when the elite members of a British feudal society were in large part following a rigid Christianity, where more localized religions focused on pagan beliefs5. In France, religion was closely related to architecture and geography given the fractionated ideals of religion during the Christian crusades. This is prevalent in the work by Shelia Bonde on the fortress-churches in the coastal town of Languedoc from the early to mid- 1200’s6. Italy saw even more growth of Christianity, more succinctly Catholicism after the fall of the Roman Empire. Although Christianity was widespread, the growth of what Trevor Dean calls “civic religion”7 were found in the countryside where churches ran as communes to aid the community they were serving.

As each nation saw the rise of Christianity, each nation also saw different and divergent ways on how the individuals managed their religion in their geographic area. This is reflective of one of the most important events relating to a breaking of religious ideals in the Middle Ages. The Great Schism, also called the Christian Schism or East-West Schism, was a rising of ecclesiastical differences between religious leaders which has not been seen since the Rome-Constantinople Schism of early millennia. Although the official excommunication between Western and Eastern Christianity was in 1054, the divide marinated over time, leading into the events of 1380 where two papacies were founded, one in the city of Rome in Italy under Pope Urban VI, and the other in Avignon of France under Pope Clement VII with social and political strife following8. The separation of the church was an example of different ideals that formed and shaped society during the Middle Ages, one might consider the interdisciplinary implications of differing opinions being presented during this time, heightening the ideal of interdisciplinarity to enhance learning, life, and society. However, it is unfortunate given the amount of bloodshed that happened in the name of religious ideals setting the groundwork for balancing interdisciplinary goals with morality.

One might make the connection between the Great Schism and the unrest that happened in religion during the crusades against the Islamic religions in the Middle Ages. The crusades provide an interesting view on learning and society outside of the realm of religion through an informed understanding on interdisciplinary knowledge transcending religious concepts. The concept of love and belief of an ideology can transcend words of God, as Riley-Smith suggests:

“The development of the idea of violence expressing fraternal love can be illustrated from the sources for the history of the Military Orders, which were linked closely to the crusade”9

Military Orders, (Latin: Militaris Ordo) provide a justification to advance the word of god to the Holy Land during the crusades, the question that remains, does the justification align with the perception? Riley-Smith also provides the sense of perception from the Islamic side as a jihad against the Islamic religion10. So even though the Christian crusades were seen as an expansion of love from the word of God; in reality, it was actually a Military expansion for control and power.

However, this could also be said of militaristic expansion by Islam of the East given the fractionation between the different Christian sects in Europe. The Ottoman Empire waged four different sieges on the holy city of Constantinople culminating in the fall of the Byzantine Empire and other papal states in Italy in 1453. One might say the Ottoman Empire under the rules of Islam is inherently violent as the Quran states:

“[By Allah] to rid of Satan’s pollution” and “cast terror into the hearts of those who disbelieve”11.

With a disciplinary framework, such as religion one may only be able to see justification rather than perception and a sense of nuance creating the clear divide between ideological love and violence.

So, what is the interdisciplinary lesson from this? The interdisciplinary lesson from religiosity during the Medieval Period is that perception can lead to justification – and when perception cannot be shaped or reframed can cause violence and depression acting as a face but also a malicious mask. Perhaps this is the interdisciplinary loss of the Medieval period, the individualized and centric bubbles that formed within the sects of Christians, Pagans, Muslims, and other beliefs to create a perception of their way is the way. One can’t help but return to the Sumerian tablets of Gilgamesh and reference the dragonfly in the sun. Individual ideology of religion is too narrow and will lose to the nature of violence when kept narrow. The interdisciplinarity in religious belief is to transcend the religion itself and create nuance discussion on how to guide a human life more than justification and perception based on dogma. Furthermore, acknowledging the terrors that happen when following a strict ideology without nuance. Keep this in mind, as the concept of religious disciplines will be used in later chapters focusing on narrow vacuums of ideologies in later centuries.

Perceptions of the Dark Age: Hidden Interdisciplinarity

The horrors of religious persecution and sectarianism from multiple sides without nuance happens to be the moniker for why the Medieval period was a dark age. The lack of combined knowledge and the bridging knowledge gaps were lost in society at large; have it be with health, wealth, relationships, and being. What makes this era truly dark was that it lasted a long time, we could say from the Great Schism in 1054 to the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, hardship lasted close to 400 years reflecting a true psychological and sociological darkness that came to an acceptance by people that this was a way of life. Low life expectancy and high mortality were considered average especially since the physical health and wellbeing of people were connected to their religion which creates a negative feedback loopb that is hard to break. However, with a deeper look it might not seem all doom and gloom. We might be able to find some instances where things happened through an interdisciplinary mindset and developed a glimmer of light in these dark times.

The dark age may have guided strict lenses on learning pertaining to religion, but it didn’t subdue the hunger to learn more. In England, the University system began to form with The University of Oxford dating back to 1096, and more formally 1167 when Henry II banned English students from attending the University of Paris12. Perhaps in a twist of irony, the warring, ideological, blood feud between the English and the French gave rise to a new way in the form of the doctrina or scholarship for humans. This was further expanded when Oxford town members had disputes and friction on lodging prices, exploitation, and ideological differences. This did not lead to bloodshed, it led to individuals in nearby Cambridge to start their own knowledge institution of Cambridge University in 120913. The example of the university in Medieval Europe is a way of expanding beyond the rigid thinking of the time; sure, most of the teachings were based on the magistrate and the Christian doctrine, but the separation and dissenting views provide the basis for an interdisciplinary development of knowledge.

This of course led to new ways of thinking in the forms of learning, life, and society. More succinctly knowledge used the tenants of religion but expanded them beyond anything that religion could fathom. It was in the words of Geoffrey of Vinsauf who wrote the Poetria Nova between 1200-1216 which outlines the building of writing and poetry as a natural form of expression:

“Let the part of the material which is first in natural order wait at the entrance of your work; let the end, an apt forerunner, enter first and pre-empt a place – as if it were a more distinguished guest or even the master himself. Nature has placed the end last in order, but art shows difference to it, and, taking up the lowly, raises it on high.”14

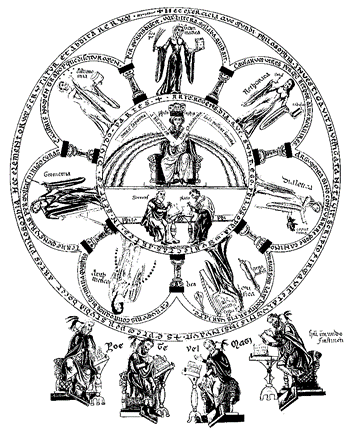

Geoffrey makes many mentions of roads leading to writing which is similar to the understanding of the liberal arts, which in a Medieval framework can be dated as far back as Boethius and his development on the understanding of rhetoric. Boethius coins the seven roads of liberal arts called the trivium and the quadrivium. This is explained through his work in the Topica Boetii in 522 through is section of the Structure of Rhetoric:

“The answer is that the species are very closely bound in with one another. There are indeed many constitutiones in a case; but they are no more parts of cases than status is part of the species. This is all the more clear because no species strengthens another species opposed to itself insofar that content is concerned; however each constitutio adds strength to every other constitutio.”15

The combination of sciences such as music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy (quadrivium) along with the higher order humanities topics of grammar, logic, and rhetoric (trivium) all intertwine together in the concept of liberal arts and early university education. It is safe to say that the classical and modern university system is founded upon the interdisciplinary connection of the liberal arts. This then introduces a concept of learning that sets the stage and the tone for how life and society intertwine.

During Medieval England, the feudal system of economics created a clear distinction of class between the rich and the poor. According to Mate, the economies were controlled in much part by the King and the pastoral economy along with fractionated legislative systems of the aristocracy. This, which imposed a deflation, where agrarian peasants benefited from cheap prices for goods, but were also deterred through their products being mightily undercut when they sold goods16. This was an issue of competition, not between goods, but the competition between production and the people to produce. It was common, due to the black plague that people did not live long, which led to less work and less production. An excess supply according to Mate where products like grain and wool being produced more than the market could handle, and that revolt was inevitable given the mass social, political, and economic factors from all instances17.

Feudalism’s first blow was with the writing of the Great Charter of Freedoms or what is commonly called the Magna Carta by Archbishop Stephen Langton, which outlined many factors of social, political, and economic reforms for the feudal system of Medieval England. This provides a theory of growth to which the advancement in technology played a massive role in the dire economy exiting out of its feudal and tumultuous state. As Professor of British Medieval History John Langdon suggests, the new network of agricultural mills were a gateway to new economic expanses, this led to advancement in waterpower in the iron-making and forging process18. Economic perception seems to showcase a natural lineage between knowledge and technological change – much like past epochs, the growth of knowledge proliferates through many factors of society.

Another topic of growth happens to be the growth of medicine during the medieval era which came out of a dire need to stop the spread of the Bubonic Pestilence. We return to the trivium and quadrivium as being the basis of the early Medieval university and try to understand this in the realm of medicine. However, according to John Riddle the method of medicine was, and continued to be considered an art as opposed to a science, proliferating from Hippocrates19. Therefore, the need for medication was more of an aesthetic than a societal stabilizer to which we see medicine today. It was through this liberal arts advancement that medicine made itself a science away from an art, and into the realm of the profession20. In addition, the causes of the Black Death acted as a re-growth or renewal of knowledge within learning, life, and society. Getz describes the ability to transform history was a generally positive effect of the Black Death21 and medicinal advancement was a part of that transformation acknowledging beneficial methods, and unfounded mendacities.

When discussing knowledge, economics, politics, society, or medicine, we can see that epistemological aspects were present in the Medieval era. Unfortunately, they ran parallel with other social, health, political and knowledge hardships. The connection of knowledge and advancing the life and society of individuals were present, but being subsided through religious dogma, papal or royal power, and natures wrath on health could be caused for the interdisciplinarity to be lost in the fog of Medieval history.

Where are you Interdisciplinarity?

Yes, given the horrors listed by historians during the Medieval period suggesting that knowledge was lost under the feudal rule of lords and priests; interdisciplinarity finds a way into the conversation not only as a natural occurrence, but as an immune response to the epistemological and sociological challenges that the Medieval era produced. The virus of control, subservience, and disillusionment is counteracted and fought by expanding knowledge, rationality and understanding to combat the feudal nobility and papacy of the era. The significance of education starting with the doctrine of the church, but then expanding ideas outside of the church walls for the benefit of the individual and society. This is the new perception of the Medieval Age, the middle section between previous knowledge and expanded knowledge.

In finality, that glimmer discussed at the beginning of the chapter through the question: were the Middle Ages a truly dark time for interdisciplinarity? A basic perception would be that it was a dark time, but if it was not for these dark times, the resilience and fortitude of human beings to advance their knowledge in learning, life, and society we would not found and expand upon new ideas. It would be seen as quite macabre to say, but we can thank the mayhem of the Medieval Ages insofar that they advanced the resilience of human beings to find a better way of life, much like we can thank the tumultuous mayhem of our solar system that gives us the Earth and the Moon. It is through the connection of knowledge and an interdisciplinary nature that helps individuals find answers to complex questions such as developing medicine in the face of a plague, or creating new technology and economies in the face of production and oppressive feudal systems, and develop new forms of thinking and knowledge in the face of rigid and oppressive religious dogma. We can use the Medieval Age as an example to look at history as we move into sunny days with the Renaissance and Enlightenment Age using the Medieval Era as a cautionary tale to not hold back knowledge and the advancement of an interdisciplinary nature.