Security and Locking Up

Allison Glazebrook

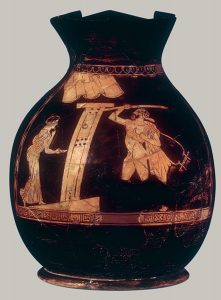

The woman depicted on this vase hesitates to open her place to a late night reveller who bangs the door with his walking staff. She is right to be cautious. The defendant in a court case relates to the jurors how a man named Simon arrived at his house drunk one night and broke down the doors (Lysias 3.6-7). The defendant was not at home but his female kin were. Simon pushed his way in among the women and refused to leave until those accompanying him and some neighbours forced him out. It’s not the only time a speaker in court recounts a home invasion. At another trial, a speaker recounts how his enemies unlawfully entered his home in his absence and began to remove his personal property, including sheep and enslaved workers. They even attacked an elderly freedwoman who attempted to hide some valuable items on her person (Demosthenes 47.52-53). What measures were taken to secure a house and its contents and protect the people within?

While the Greeks did not have electronic security systems, they were very much concerned with security. The textual evidence makes clear that householders locked their doors and kept storage items safe within the house. A play of Aristophanes, for example, mentions the use of a bolt and padlock to secure the main entrance (Aristophanes, Wasps 152-55). Valuable items could be locked in a chest (Demosthenes 25.61; Lysias 12.10) or even buried in a cache beneath the floor of the home (e.g. Houses A v 10, A vi 8, and A 11 at Olynthus). Sleeping quarters seem to have been considered the most secure area of the house and were where wealth and other valuables were kept (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 9.3). Quality of construction would also have been a factor in security. Since houses were commonly of mudbrick, a poorer construction might easily be penetrated by digging through the wall. The wealthier the individual, the greater potential (and likely need) for security

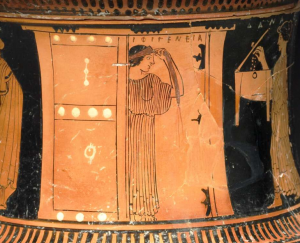

In this image, a woman opens one of the doors in a set of double doors to a second woman holding a box. Metal bosses visible on the closed door decorate and reinforce

the wood. A long keyhole is shown in the top half of the door and a round hoop handle appears attached to the lower half.

A common way to secure a door was with a sliding wooden bolt. The bolt was moved into place by a rope or strap of leather.[1] Keys were long angular metal rods that inserted into a hole in the door to push the bolt back and open the door. Keys have occasionally been found in archaeological excavations. A fine example is a bronze key in the shape of a snake from the Temple of Artemis at Lousoi.

Entrances to houses might require the visitor to pass through a porch and a second set of doors, adding a further level of security (e.g. House A iv 9 at Olynthus). Having a secured location within the home was another way to keep the inhabitants and wealth safe. When men unlawfully invaded a home to seize the property, the enslaved women closed and secured the door to a tower and prevented the men from entering that part of the house. The women were inside the tower at the time of the invasion and so the locking mechanism was on the inside of the door (Demosthenes 47.56).

Threats from Within

The owner of a large estate, Ischomachus, recommends housing enslaved members of the household in male and female quarters separated by a locked door (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 9.5). Interestingly, Ischomachus does not suggest the locked door to prevent enslaved workers from self-emancipating, but to prevent stealing and sexual relations without his permission. This example not only shows how much control enslavers had over enslaved workers in their households, but also their mistrust of such workers. Household security, in the Greek mind, focused on insiders as well as outsiders. Only the view of the wealthy landowner survives and so what enslaved people thought about their personal security or what measures they took to protect themselves and any personal goods in these households are not known.

Careful inventory and bookkeeping would have been another way for households to ensure their goods were secure. In Ischomachus’ home, it is the wife who oversees the running of the household, including keeping an inventory of everything that comes in and goes out. It’s her responsibility to make sure all items stay in the right place and to note any discrepancies. She acts as the “guardian” of all items in the house The male head (kurios), given the absence of a police force, is responsible for protecting the household, its members, and its contents from outsiders (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 7.25, 9.14-17). While resorting to violence against an intruder was an option, bringing the offender before a magistrate and prosecuting the offender in a court of law for theft or assault were also possible and socially preferred to escalating a situation.

Home security was very much a concern for the ancient Greeks. In Athens we see that security was both a personal concern and also of interest to the city. Householders took measures to secure their homes and any violation of a household, its members, and its wealth had legal recourse.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Andrianou, D. 2009. The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cahill, N. 2002. Household and City Organization at Olynthus. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fisher, N. 1998. “Violence, Masculinity, and the Law in Classical Athens” in When Men were Men: Masculinity, Power and Identity in Classical Antiquity edited by L. Foxhall and J. Salmon. 68-97. New York: Routledge.

- Tsakirgis, B. 2016. “What is a House? Conceptualizing the Greek House” in Houses of Ill Repute: The Archaeology of Brothels, Houses, and Taverns in the Greek World edited by A. Glazebrook and B. Tsakirgis. 13-35. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- https://www.historicallocks.com/en/site/h/other-locks/locks-of-wood-and-iron/sliding-bolt-locks/ ↵