From the Ground Up

Basil Tabes

The ancient Greeks have been revered throughout history for their extravagant monumental architecture. The production of domestic structures, however, is often overlooked. The household was the base of Greek society, and one can not have a household without the house itself. As magnificent as they are, temples and theatres are not suited for people to live in. The construction of houses in Classical Greece did not differ significantly from the modern era, and much of the process is still actively used today.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of Greek houses have been reduced to just the foundations over the millennia, meaning that much information regarding the construction of the house remains unknown. Luckily, there are extant written sources that help paint a picture of what these buildings would have looked like when they were inhabited. The philosopher Aristotle offhandedly mentions the management of balcony measurements in his Athenaion Politeia (50.2) and other features that have been completely lost in the archaeological record. Despite living hundreds of years later, the Roman architect Vitruvius wrote down his observations on how the Greeks built their houses in his De Architectura (2.8.5), providing us with the most detailed descriptions of Greek domestic architecture.

The average house in Classical Greece was made out of relatively simple materials. The typical house had a foundation utilizing stone as the main component. One of the most common methods of foundation construction was rubble masonry. Relatively small, irregular stones were gathered and stacked into a wall, and may have been cemented with mortar to ensure they remained in place.

The other most common type of masonry was ashlar masonry. This type of masonry consisted of carved stone blocks tightly arranged in neat rows. These blocks varied in size, ranging from the size of a brick to massive slabs. These were most commonly carved out of limestone, which was often gathered from a nearby quarry. In situations where there was no nearby quarry, or if the builder desired a higher quality material, stone was imported from outside sources. Out of these two, rubble was the more cost-efficient method since it required less labour to produce by using debris instead of hand carved stone.

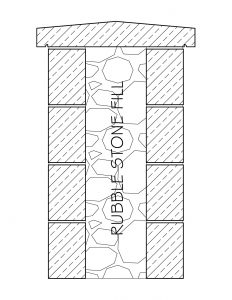

The walls that sat on these foundations were most commonly made of mudbrick, a material still commonly used today (Adobe is a common example). Mudbricks were comprised of a mixture of soil, sand, and water that were then pressed into blocks and left to dry in the sun. In many cases, the bricks were strengthened by the addition of straw into the mix, or were fired in a kiln to produce a stronger material. Although it was inexpensive and versatile, mudbrick was not nearly as durable as stone, and often had to be supplemented with stronger materials. In this case, the bricks would be arranged in two parallel lines with a hollow in the middle, which would then be filled up with stone debris (and sometimes mortar) to make the wall sturdier. Wooden beams would often be inserted in these walls and covered up to provide support while also keeping the space open.

Like with many of their temples, the roof of a house was covered in overlapping terracotta tiles. Terracotta roofing acted as a midway point between the earlier materials, lightweight but weak wooden/thatch coverings and the sturdy but heavy stone tiles. This allowed the Greeks to create larger, more open structures while also maintaining a high degree of insulation and protection.

Plaster was one of the most important materials in the ancient world. Made from a combination of powdered lime and water, plaster served a multitude of purposes. Once the structure of a house had been built, the walls were most often then covered in a layer of plaster. The main purpose of this is to act as insulation, creating a solid layer around the walls. This protected the mudbricks from damage that would be inflicted by water, weather, or being struck, allowing the walls to go longer without need of repairs. Plaster was also popular for its use as an artistic medium. While most of the time the plaster was left bare, it was common for artists to paint frescoes on wet plaster. A famous later example of this technique are the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Painted plaster is more common in wealthier houses, as the upper classes would be able to afford artisans.

The Bigger the Better?

When thinking of what a wealthy person’s house in ancient Greece would look like, most people might imagine a massive, luxurious country villa. While these certainly did exist, for the most part wealth did not play a significant role in the size of houses. Many houses, especially in heavily urban areas like around the Athenian agora, were all roughly the same size.

As the houses themselves were all relatively equal, wealthy members of society had to compensate with interior decoration. This would often be done with elaborate artwork, such as plaster paintings, stone carvings and mosaics. For example, mosaic floors depicting scenes from Greek mythology have been found at the site of Olynthus, something that would have distinguished the owners as being wealthier than the average family, who would have had simple bare floors. Since social image was an important part of Greek society, wealthy individuals would make sure to beautify the inside of their homes to flaunt their status to any guests.

Once all the materials were gathered, the house actually had to be put together. There are few sources describing the actual construction process, but from what has been found we can divide the people involved into two broad categories. There were the general labourers and the specialists. The actual building of the house fell on the general labourers. These were people who put the entire structure together, similar to modern construction workers. Specialists were more extensively trained in a specific field. For example, while the house was built by a general team, there may be a few people who are well versed in the creation of drainage systems, or a professional stone carver.

While room use in the Greek household was very flexible, certain rooms required permanent specifications in order to be used properly. For example, floors of designated bathrooms would often be waterproofed with a thick layer of plaster. Fixed hearths, while not as common as portable braziers in the Classical period, were built directly into the structure itself, and therefore required extra specifications. Chimneys then had to be built into these rooms to prevent smoke buildup.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Antonaccio, C. 2000. “Architecture and Behavior: Building Gender into Greek Houses.”Classical World 93: 517-533.

- Aylward, W. 2011. “Security, Synoikismos, and Koinon As Determinants for Troad Housing in Classical and Hellenistic Times.” In Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity edited by B.A. Ault and L. Nevett, 36-53. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

- Ault, B.A. 2011. “Housing the Poor and Homeless in Ancient Greece.” In Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity edited by B.A. Ault and L. Nevett, 140-159. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

- -. 2000. “Living in the Classical Polis: The Greek House as Microcosm.” Classical World 93: 483-496.

- Gardner, E. 1901. “The Greek House.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 21: 293-305.

- Lang, F. 2007. “House — Community — Settlement: The New Concept of Living in Archaic Greece.” In Building Communities: Home, Settlement and Society in the Aegean and Beyond edited by R. Westgate, N.R.E Fisher and J. Whitley, 183-193. London: British School at Athens.

- -. 2011. “Structural Change in Archaic Greek Housing.” In Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity edited by B.A. Ault and L. Nevett, 12-35. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.