At the Margins

Shakeel Ahmed

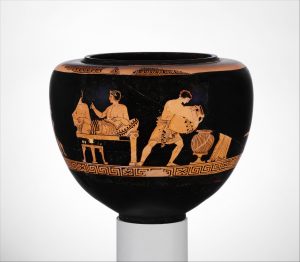

Who are the people at the margins of the Greek household? The imagery around this circular vase captures a moment of an all-male social gathering (the symposium ) in a Greek house. The artist wants us to observe the whole imagery as a continuous action, like a clip of a scene in a movie. But the inclusion of a bulky young man holding a large vessel in his arms arrests the progression of the scene momentarily.

Attributed to the Group of Vienna 4013,

c. 375–350 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York. Rogers Fund, 1914.

He is seen pouring some liquid (likely wine) from an amphora into a container where the wine would be mixed with water (Greeks saw virtue in drinking diluted wine ). A man and his companion, reclined on a couch, seem oblivious to him and his task. Their disinterest pushes the young man to the margin of this scene. His location at the margin, along with his task and clothing (a short tunic wrapped around the waist), confirm his social status as an enslaved domestic labour. The artist’s choice in depicting him thus seems appropriate when we consider that the Greek household privileged free-born citizens over enslaved individuals.

It is generally thought that the average Athenian household had at least one enslaved labourer. Such persons performed various tasks ranging from childminding and working looms to working alongside their enslaver (of course, not wealthy ones) in agriculture and household industry (see below and chapter 10). Any manual task would be carried out by the enslaved members of the household.

This vase image shows a young man moving heavy furniture, a sympotic couch and a table slung over his shoulders. He is nude, but his build is not particularly athletic. His bent legs and the left foot slightly raised off the ground suggest that he is struggling under the weight of the furniture. His unremarkable physique and un-heroic nudity symbolize his social status as a domestic enslaved labourer.

In the fifth and fourth century BCE, Athenian society was a slave society because many enslaved and formerly enslaved populations influenced its socio-economic landscape. The roles and functions of enslaved people thus contributed to the financial success of the Greek household. In some instances, the enslaver relied on enslaved labour to maximize profits in his trade. Sometimes he worked alongside them and drew the same wage; an Athenian inscription shows that during the construction of the Erechtheum the stonemason Phalarkos worked with his enslaved workers fluting the columns of the east porch (IG13 Erechtheion). Other workers may have lived and worked apart from the enslaver practising a trade or manufacturing products to sell in the market and paying a share of their income to their enslavers (Aesch. 1.97). A law court speech shows that an Athenian purchased a skilled enslaved man, Midas, and his two sons, along with their perfumery business (Hyperides Against Athenogenes 4-27). There is no indication that the enslaver shared his living space with the family of Midas. Perhaps they lived as well as worked at the perfumery. The absence of a mother highlights the tragic incompleteness of the family. Moreover, Midas and his sons change hands from one enslaver to another when they are sold. This case shows that despite having a steady source of income and some independence as enslaved workers” “living apart”, enslaved families lived under the constant fear of separation or drastic change in their living situation (Hyp. Ath. 5).

The fact that enslaved people could earn an income in ancient Greece alerts us to the fact that enslaved individuals could buy their freedom. What was life like for freedmen and women in ancient Greece? Enslaved males likely had an easier time after being freed. Athenian lawcourt cases highlight the vulnerability faced by women in particular who were voluntarily freed by their enslavers or who managed to buy their freedom. We should remember that many enslaved people had to work for a long time to save enough money to buy or be given their freedom. That meant they spent the better part of their lives in slavery. Many never had an opportunity to start a family (Xenophon Oeconomicus 9.5). These people could find themselves isolated outside the enslaver household. The incidental death of a freed and retired nurse at the hands of two Athenian men highlights the risks for freed people living outside of legally recognized households. The old nurse had moved back in with her former enslaver after her husband’s death; having no children, she likely had nowhere else to turn to after serving the household for the greater part of her life. Since she had been released from enslaved status and had no known relatives, Athenian law did not permit her ex-enslaver to prosecute the two men (Demosthenes 47.55-72). In another case, the famous sex labourer, Neaira, drifted from one place to another, trying to establish a household for herself and her children after earning her freedom from a brothel house in Corinth (Demosthenes 59.18-73). In this case, she continued to work in the sex trade until she eventually found stability as the live-in companion of an Athenian man.

Enslaved People as a Mark of Status

Archaeological and textual evidence shows that enslaved labour, besides significantly contributing to the household’s surplus income, also assisted their enslavers (the husband and the wife) in day-to-day activities.

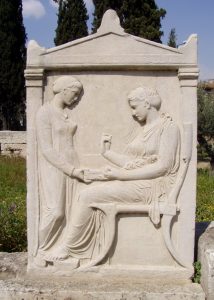

This funerary stele depicts a young, lean, petit woman in a plain long-sleeved chiton helping her enslaver mistress with her jewellery box. The depiction of a comfortably ensconced woman, much larger in size with an elaborate hairstyle and voluminous chiton, highlights the woman’s status as an Athenian wife belonging to a wealthy household. Could an emotional connection have existed between these women despite the disparity in their social status? The inscription on the stele bears one name only, identifying the seated woman as Hegeso. She, and not her connection to the enslaved attendant, is the focus of attention on the tombstone. Her dominant frame contrasts sharply with the slender girl standing at the margin. Greek artists regularly used size and other physical characteristics to distinguish between free and enslaved people. In this case, the unnamed enslaved attendant highlights Hegeso’s social status and wealth, much like the jewellery box, rather than any intimacy between the two women. In addition to their labour, enslaved people served as markers of their enslaver’s wealth and status.

The case concerning the sale of Midas and his family also draws our attention to the sexual exploitation of enslaved people by free citizens. The prosecutor claims that because of his passion for Midas’ youngest son, he agreed to buy the father, his two sons, and their business and not tear apart the whole family. But it also gave him guaranteed sexual access to the young man. Citizens’ involvement with enslaved men and boys did not complicate household affairs, as did citizens’ involvement with enslaved or freedwomen engaged in the city’s entertainment business. Citizens’ relationships with such women could result in children. These women and children threatened Greek households’ wealth and ideological structure, which only granted citizenship to children born to two citizens.

Two sons of a deceased Athenian man, Euctemon, from his relationship with a woman not connected to a recognized Greek household, are at the centre of a property and inheritance dispute in another lawcourt speech (Isaeus, On the Estate of Philoktemon 6.5-28). The prosecutor claims that the sons’ birth mother is Alke, a formerly enslaved sex labourer and a brothel keeper. The speech plays with Athenians’ anxieties over the role of enslaved women in the household and their place in the city as sex labourers. The speaker appeals to the jury to consider the extraordinary stress Alke has caused the legitimate wife of Euctemon’s household. Highlighting her role as a sexual companion, her transgressive mobility in the city, and her habitations at various marginal and less-reputable locales, the speaker paints Alke as a typical companion/ entertainer/ sex labourer who is threatening to break up the legitimate household and rob its legal members of their wealth. The prosecutor strategically stereotypes Alke as an alien woman living beyond the code of decency, looking for the opportunity to fool a citizen of a wealthy household to claim his inheritance and pass off her illegitimate sons as citizens— a significant violation of the laws since only legally recognized Athenian women citizens could bear legitimate children who had a claim to the household. There was no legal prohibition, however, against citizen men’s involvement with alien/enslaved/freed women in the entertainment and sex trade. Wealthy men like Euctemon could afford to set up another house for their mistress (See also [Dem.] 48.53-56 and [Dem.] 59.114). Yet such court speeches also highlight the hardship in the lives of these marginalized women as they try to leave the sex trade and set up a stable household.

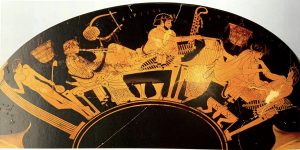

Enslaved women also entered the household for all-male gatherings in the andron, from which women-folk were excluded. Enslaved women were invited as hired musicians, dancers, and companions for the male guests’ entertainment. In this vase painting, male guests are entertained by a flute player and a female sexual companion. The inside of the cup also depicts a female dancer. The physical contact between the reclined man and the woman on the right side of the scene shows that entertainment and sex were closely linked in male social gatherings. The presence of an enslaved man at the margin of the scene, leaning against the pillar and quietly observing the proceedings, makes us acutely aware of his low status and his role as server of the guests.

We should remember that all the ancient evidence discussed above preeminently relays the elite male perspective. So, our view of the enslaved experience is limited; at best, it only captures glimpses of reality. Furthermore, the evidence that at first glance shows close ties between enslaved and free might instead demonstrate the emotional labour required of enslaved people in these relationships. Enslaved people needed to obscure their own feelings and desires in the presence of the enslaver in order to be successful in a slave society.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Fisher, N. 1993. Slavery in Classical Greece. London: Bristol Classical Press.

- Glazebrook, A. 2006. “The Bad Girls of Athens: The Image and Function of Hetairai in Judicial Oratory.” In Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World, edited by C.A. Faraone and L.K. McClure, 125-38. Madison (Wisc.): University of Wisconsin Press.

- —. 2021. Sexual Labor in the Athenian Courts. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Golden, M. 2011. “Slavery and the Greek Family.” In Cambridge World History of Slavery, edited by K. Bradley and P Cartledge, 134-52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, J. 2010. The Classical Greek House. Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press.