The Andron

Ashley Rydzik

The andron: a place where Greek men wined, dined, and socialized during an event called a symposium. In many ways, a symposium could be considered similar to what we refer to as a ‘house party’ today – people get together, consume food and drink, listen to music or another form of entertainment, and socialize with one another.

There were even times during symposia when men would drink too much wine (the primary beverage consumed at these events) and make themselves sick – a feeling that is all too familiar to many at a house party. An ancient representation of said debauchery is depicted in the vase painting shown on the left. Although parallels can be drawn between symposia and house parties, there are several stark differences, especially when discussing the gender division of the andron. This chapter will explore the andron and the symposium, and will answer questions regarding the function and organization of both.

The andron was a room found in some, but not all, Classical Greek houses. Architecturally, this room is often identified by its square shape and raised cement borders, which presumably held the klinai, the couches that guests reclined on during symposia. Pebble mosaic designs sometimes adorned the middle of the floor, such as the mosaics found in rooms at the Villa of Good Fortune. The andron was largely separate from the rest of the house, often with an antechamber preceding its entryway and an offset door.

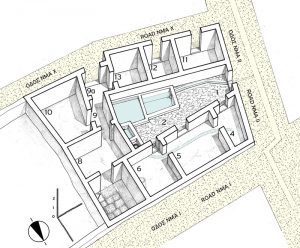

This design was thought to be done to ensure that women were completely separate from the events that took place in the andron and to prevent them from seeing or interacting with those who were attending a symposium. It supports the concept of separate gendered spaces for men and women in classical Greece. See, for example, House Θ to the right. In this house’s grid plan, room 7 is thought to be the andron, with room 8 being the antechamber. Scholars think room 7 to be the andron because of the raised cement borders and mosaic tiling that remains. The image at the bottom of this page shows the actual remains of House Θ from one of the exhibition areas at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. It is important to note that although all androns may have had the same function, they certainly did not all look the same. Discrepancies between androns can likely be attributed to status, as the wealthy would have been able to better adorn their space than poorer citizens.

So, what did an ‘average’ andron look like, and is it possible for us to identify it in the material record? Literary sources, such as Lysias’ On the Murder of Eratosthenes (1.9), describe the andron as a flexible, rather than a permanent space. These texts suggest that the andron, and its symposium (the main event that took place in the andron) were portable, and did not necessarily have to take place in a designated area of the house. Lysias’ work demonstrates this well as Euphiletus is able to move his andron upstairs when needed. A fairly common conception is that the andron and symposia were only for wealthy, elite men. The above evidence, however, offers an alternative idea – that ‘average’ androns existed, but they just did not survive archaeologically because of their temporary nature (compared to the more structural permanency of elite, cement-bordered androns).

The literal meaning of andron is “of men,” implying that the andron was a space for men only. But androns were likely multi-functional spaces as is hypothesized for the rest of the Classical Greek house. Thus, the andron was not simply used for symposia (male drinking parties), but rather had different uses at different times dependent on need. Androns could even be used by women for household activities such as weaving, which is evident by the presence of loom weights in typical andron rooms at Olynthus. Additionally, we know that during symposia it was not solely male citizens who were present. Enslaved people, entertainers, and prostitutes, many of whom were female, played a key role at symposia, although one that was much different from the elite men hosting and attending the event. Men and women did not have the same status and rights in ancient Greece, especially not the women attending symposia as they were not deemed “respectable.” They could be forced into sexual submission with impunity – a sad reality that is often overlooked when studying ancient symposia. Such violence is what the famous sex labourer Neaira experienced when she attended a victory party with her lover Phrynion ([Dem]. 59.33-34).

The symposium was the fundamental social institution in ancient Greece – particularly in Athens. It consisted of a small group of men convening in the house of a friend for an evening of drinking; there may have been a meal beforehand as well. The men reclined on couches, sang, told stories and philosophized, and gazed at the hired entertainers, as can be seen in the depiction of a symposium on the drinking cup to the left. Said entertainers ranged from musicians and acrobats to hetairai – trained sexual companions. But the importance of the symposium did not lie in the event itself, but rather the overall atmosphere it produced. Communal drinking activities were intended to forge and emphasize group identity – a concept that was as crucial to democracy in classical Athens as it had been among the aristocracy of archaic Greece. The change to democracy saw the coming together of people from all over Attica and from all walks of life, and so establishing a collaborative social environment among the citizen men was essential – and the most acceptable way to do so was through drinking.

The Art of Mixing Wine

The drink of choice was wine mixed with water in a large mixing vessel called a krater. Mixing was done in order to ensure the symposiasts maintained their composure and self-control – traits that were highly valued in ancient Greek society. It was believed that only uncivilized peoples drank unmixed wine, and the Greeks thought themselves to be much better than their non-Greek counterparts. But were the Greeks really any better? The dilution did not keep the men sober as they consumed on average between 4-5 kraters per night. Thus, evenings often ended in drunken debauchery, with symposia often getting out of hand and leading to destruction of property and injuries. This is discussed briefly in Plato’s Laws, as he describes how excessive drunkenness, such as occurred at symposia, could lead to fighting, vandalism, and other seditious acts (1.637a-640).

The symposium itself mirrored the nature of Greek (namely Athenian) culture and society and, as politics and history affected the people of Athens, they also affected the microcosm of life in the symposium. The environment of the symposium was designed to uphold equality, just as the newly founded democracy was designed to do. There were, however, two essential, but conflicting, characteristics of Athenian society – egalitarianism (democracy) and an agonistic spirit (the desire to be the best; resulting in competition, such as at the ancient Olympics). The symposium breeds this same tension, since there was the underlying concept of equality, but also the desire to have individual recognition among one’s peers. This desire led to the incorporation of status into the ‘status-less’ environment of communal drinking, as men would attempt to show off their wealth through the luxury of their andron, entertainment, and refreshments. See for example the mosaic floor in the House Θ andron shown above, and another in chapter 2 “From the Ground Up”.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Lynch, K. 2007. “More Thoughts on the Space of the Symposium.” In Building Communities: Home, Settlement and Society in the Aegean and Beyond edited by R. Westgate, N.R.E Fisher and J. Whitley, 243-249. London: British School at Athens.

- Nevett, L.C, et al. 2017. “Towards a Multi-Scalar, Multidisciplinary Approach to the Classical Greek City: The Olynthos Project.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 112: 155-206.

- Morgan, J. 2011. “Drunken Men and Modern Myths: Re-Viewing the Classical ἀνδρών.” In Sociable man: Essays on Ancient Greek Social Behaviour in Honour of Nick Fisher, edited by S.D. Lambert and D.L. Cairns, 267-290. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales.

- Robinson, D.M. 1934. “The Villa of Good Fortune at Olynthus.” American Journal of Archaeology 38: 501-510.

- Westgate, R. 1997. “Greek Mosaics in Their Architectural and Social Context.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 42: 93-115.