Week 12: Indigenous and Colonial Relationships, Effects of Colonialism Part 4

Canadian Colonial Relations

The British North America Act received royal assent on March 29, 1867, and on July 1, 1867, it went into effect, creating the Dominion of Canada. The Act would define the political structure and the form of Government as a parliamentary government. Initially, there were four provinces with a provision for other British territories in North America to negotiate entry into the dominion. The new federalist dominion would remain under the sovereignty of the British Monarch for the next 115 years.

The Indian Act of 1876

Indigenous relations were one of the most critical items for the new parliament to consider. The indigenous population needed to be accounted for and controlled. Nine years later, it would enact the infamous Indian Act of 1876. “As a deputy minister of the Indian Affairs Branch noted: ‘The Indian Act is a Land Act. It is a Municipal Act, an Education Act and a Societies Act. It is primarily social legislation, but has a very broad scope; there is provisions about liquor, agriculture and mining as well as Indian lands, band membership and so forth. It has elements that are embodied in perhaps two dozen different acts of any of the provinces and overrides some federal legislation in some respects . . . It has the force of the Criminal Code and the impact of a constitution on those people and communities that come within its purview.'”113

Indigenous relations were one of the most critical items for the new parliament to consider. The indigenous population needed to be accounted for and controlled. Nine years later, it would enact the infamous Indian Act of 1876. “As a deputy minister of the Indian Affairs Branch noted: ‘The Indian Act is a Land Act. It is a Municipal Act, an Education Act and a Societies Act. It is primarily social legislation, but has a very broad scope; there is provisions about liquor, agriculture and mining as well as Indian lands, band membership and so forth. It has elements that are embodied in perhaps two dozen different acts of any of the provinces and overrides some federal legislation in some respects . . . It has the force of the Criminal Code and the impact of a constitution on those people and communities that come within its purview.'”113

113Schmalz, Ojibway, 196 quoting Franz M. Koennecke, “Wasoksing: The History of Parry Island, an Anishnabwe Community in the Georgian Bay, 1850-1920” (MA Thesis, University of Waterloo, 1984), 263.

“The new Act would become the single most influential object used by the Government of Canada to control our lives. Its control was dictatorial and its influence suffocating.”[1]

The new country had expansionist ideas from the start. Its first Prime Minister, John A MacDonald, had a vision of connecting the east coast of North America with the west coast via a railroad. As settler expansion moved west, more and more land would be required. The new Government would use the Indian Act to empower it to complete land surrender treaties with First Nations, often by coercion.

The keystone of Indian policy for the Dominion of Canada would be assimilation. Every action taken by the Government would be designed to assimilate First Nations into the dominant culture. Assimilation would continue to be official government policy until the Revision of the Act in 1985 when they would revert to a nation-to-nation dialogue.

A considerable bureaucracy called the Department of Indian Affairs would administer the Indian Act. The department’s structure would be top-down with no power making decisions below the Indian Agent. The Indian Agent had total discretion when setting local policy or making decisions affecting his reserve. Politicians often handed out these patronage appointments for favours granted by friends or relatives, which usually ended with Indian Agents unqualified for the post.

The Indian Act of 1876

Department of Indian Affairs

Excerpt from David D Plain, The Plains of Aamjiwnaang, Trafford Publishing: Victoria, B.C. 2007, pp127-129.

I do not intend to paint a picture of total corruption and abuse. There were some good Indian agents. There were also many good missionaries, ministers and priests. Many of these spoke out against the oppressive domination of the prevalent society, but they were visionaries far ahead of their time and notably in the minority.

One such figure was Froome Talfourd. He took over the visiting superintendency at St. Clair in 1858. Upon doing so, he found that we had lodged numerous complaints about missing moneys from land transactions and late payments from such large corporations as the Grand Western Railway Company. He investigated and found the discrepancies in the Land Account Books indicated that embezzlement was involved. He reported this to Lord Bury, the superintendent general of Indian affairs.121

This was one of many incidents in which Talfourd stood up on the side of his First Nations charge. So fair, honest and upright was he in his dealings with the St. Clair Reserve that he quickly gained a highly regarded reputation among us, so much

120Schmalz, Ojibway, 208.

121Ibid.,169-170.

128 David D Plain

so, in fact, that we instituted a feast in his honour. Nicholas Plain Jr. writes in his 1951 short history, “Among the Indians he was known as ‘The Englishman who keeps his word.’ . . . The Indians of the Sarnia Reserve tendered him a banquet on his birthday, November 4th . . . The Talfourd Feast was one event in the year that no Indian missed. Even the aged and sick had steaming plates of food delivered to their homes.”122

During the months of March through June 1891, a series of four articles appeared in The Canadian Indian under the pseudonym of “Fair Play”.123 The articles advocated cultural synthesis rather than cultural replacement (forced assimilation). Cultural synthesis is defined as encouraging “the synthesis of two cultures, that retains the elements of both, and that encourages the voluntary borrowing and adaptation by the weaker cultural system . . . the cultural components from different societies will be combined in ways that make sense to the borrowing society”.124

The articles also advocated a high degree of political autonomy. “He suggests it would constitute no harm or menace to Canada if the Indians of Ontario ‘were permitted to have their own centre of Government – their own Ottawa, so to speak; their own Lieutenant-Governor, and their own

Parliament’ “.125 These few grand ideas of the latter half of the

122Nicholas Plain, The History of Chippewas of Sarnia and the History of Sarnia

Reserve (Sarnia, ON: Privately Printed, 1951), 30.

123Nock argues that the author of the “Fair Play” articles was E.F. Wilson, despite the fact that the thrust of the articles went against the grain of the policies of the Shingwauk residential school, an institution founded and run for the first twenty years by him. See David A. Nock, A Victorian

Missionary, 135-150.

124Ibid.,1-2.

125Ibid.,136 quoting Fair Play, The Future of Our Indians, Paper No. 3,

The Canadian Indian 1, no. 9 (June 1891), 254.

The Plains of Aamjiwnaang 129

19th century succumbed to the more dominant paternalism in its many forms, which reached its zenith during this time period, much to our detriment.

Viewing Assignment 1

Understanding the Indian Act:

Viewing Assignment 2

21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act:

Indian Act Revisions

Revision of 1951 and 1985

Excerpt from David D Plain, The Plains, pp129-130.

After World War II both the Government and the public at large began to question Canada’s Indian Policy. A joint committee of House Representatives and the Senate was formed to study the matter. As a result the Indian Act of 1876 underwent extensive revision. As a result we regained our right to attend traditional religious ceremonies, to drink alcohol in public places such as bars and taverns, and compulsory enfranchisement ended (except in the case of native women marrying non-native men). The revised Act also gave individual band councils more authority.126 Assimilation was still the Government’s official policy but it would now be allowed to happen gradually and would not be forced upon us.

In 1970, Jeannette (Corbière) Lavell of Manitoulin Island registered an injunction prohibiting the registrar from removing her name from the Indian Register because she married a non-

First Nations person. She used the Bill of Rights clause against sexual discrimination and won in the lower courts. However, she lost in the Supreme Court. The Indian Act took precedence over the Bill of Rights. On the other hand, Sandra Lovelace of the Tobique Reserve in New Brunswick took her similar case to the United Nations. In 1981 Canada was found in violation of an international covenant on human rights. As a result the Indian Act was rewritten to remove sexual discrimination and married First Nations women and their children were allowed to regain lost status.129

129 Schmalz, Ojibwa. 256-257.

Reading and Listening Assignment 1

The Indian Act; The Secret Life of Cananda: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-act

Residential Schools

Excerpt from David D Plain, The Plains, pp 121-122.

The assimilation policy in Canada would be taken up in earnest when the responsibility for Indian affairs was transferred to the Government of Upper Canada in 1860. This policy remained official government policy for over one hundred years. The cornerstone of this process would be the residential school. These would come under the jurisdiction of the federal Government, but the responsibility of day-to-day operations would lay with the Church. Numerous manual labour schools were founded between 1842 and 1878.109

The complicity of the Church with the policy of total cultural replacement can be seen in a letter from the Rev. Alexander Sutherland, general secretary of the Methodist Church of Canada, Missionary Department, to Laurence Vankoughnet, deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs: “Experience convinces us that the only way in which the Indian of the country can be permanently elevated and thoroughly civilized is by removing the children from the surroundings of Indian home life, and keeping them separated long enough to form those habits of order, industry, and systematic effort, which they will never learn at home”.110

Edward Francis Wilson established the Shingwauk residential school for boys at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, in 1873.

109Schmalz, Ojibwa, 181-184.

110Ibid.,181.

122 David D Plain

Wilson was an Anglican missionary sent to Canada by the English Church Missionary Society. He was the school’s first principal and remained in that post until 1893. All residential schools had the aim of providing the environment for as total a cultural replacement as possible, and Shingwauk was no exception.

Language was seen as a major key in the cultural replacement program. We were not allowed to speak our language during school, chores or play. In order to enforce the ban we were rewarded for checking up on each other. This meant reporting any infractions to Wilson. When this failed, corporal punishment was meted out during the punishment period at seven in the evening. This policy against speaking our own language remained in effect until 1971.

Prohibition against all other forms of culture was also included in the residential schools’ rules. At play, we were not allowed to play any First Nations games but were made to play European ones; games such as marbles, cricket and soccer. First Nations forms of music were also forbidden. Shingwauk, like other residential schools, formed a marching band where the boys learned to play European marches and hymns. Other European cultural forms were forced upon us, such as the celebration of western holidays like Christmas, Easter and Dominion Day. Of course, participation in any First Nations feasts or religious ceremonies was strictly forbidden. These assimilationist policies continued well into the twentieth century.111

111For an excellent exposé on E.F. Wilson and his days as principal of the Shingwauk residential school see David A. Nock, A Victorian Missionary and Canadian Indian Policy (Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University. 1988), 67-100.

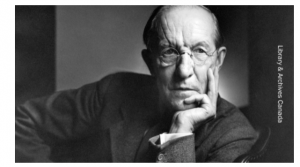

Duncan Campbell Scott was a long-time Department of Indian Affairs bureaucrat. He joined the department in 1879 at the age of seventeen. He rose steadily through the ranks until he was appointed Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs in 1913.

In 1907 the Chief Medical Health Officer, Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, issued a report on the residential schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. He reported that students were dying of disease, primarily tuberculosis. Overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions were the cause. Scott ignored the report.

Duncan Campbell Scott was also instrumental in expanding the residential school system. In 1920 he drafted a bill to amend the Indian Act to force First Nation children between seven and fifteen to attend residential school. The schools were often hundreds of kilometres from their homes. Before the bill passed, he reportedly said, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that this country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone. That is my whole point…Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department, that is the whole object of this Bill”[2]

Viewing Assignment 3

Heritage Minutes: Chaney Wenjack

Reading Assignment 2

The Residential School System: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_residential_school_system/

1969 White Paper

Excerpt from David D Plain, The Plains, p129-130

The assimilation policy culminated with Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s Liberal Government and its 1969 White Paper. This was the last official blueprint for cultural replacement and assimilation. It proposed to terminate all special rights and separate recognition of First Nations including the Indian Act, reserves and treaties. In return, First Nations people would receive the same legal rights and recognition as other Canadians.127

First Nations vehemently opposed the policy. For example, Chief Fred Plain, president of the Union of Ontario Indians at the time, countered the policy by presenting “a brief to Ottawa which would give twelve seats in the House of Commons to Indian representatives . . . He pointed out that New Zealand already had such a plan in effect for its Maori population”.128

126 Rogers and Smith, Aboriginal Ontario, 396.

127Ibid.,n18, 9.

128Schmalz, Ojibwa, 251.

130 David D Plain

This plan was not adopted, but because of the massive opposition to the White Paper it was formally withdrawn in 1971.

Reading Assignment 3

The White Paper 1969: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_white_paper_1969/

We will recognize treaty rights. We will recognize forms of contract which have been made with the Indian people by the Crown and we will try to bring justice in that area and this will mean that perhaps the treaties shouldn’t go on forever. It’s inconceivable, I think, that in a given society one section of the society have a treaty with the other section of the society. We must be all equal under the laws and we must not sign treaties among ourselves. And many of these treaties, indeed, would have less and less significance in the future anyhow, but things that in the past were covered by the treaties…things like so much twine, or so much gun powder and which haven’t been paid, this must be paid. But I don’t think that we should encourage the Indians to feel that their treaties should last forever within Canada so that they be able to receive their twine or their gun powder.” ~ Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, August 8, 1969.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission came out of The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, one of the largest class action settlements in Canadian history. The TRC was formed in 2007, with Senator Murray Sinclair, a former Queen’s Bench Justice appointed Chief Commissioner. Over the next six years, the $ 72 million Commission travelled the country interviewing residential school survivors and witnesses. It held seven national events to educate the public on the residential school legacy. In 2015 the TRC produced a six-volume final report.

A vital element of the report is 94 Calls to Action or recommendations to help facilitate reconciliation between the survivors and their communities with the Canadian public. The Calls are grouped under main headings. If you wish to participate in the reconciliation process, you should find one or more calls that speak to you and become involved with those. You can find the Calls to Action at https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf last accessed February 10, 2022.

Reading Assignment 4

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/truth-and-reconciliation-commission

Current Relationship Between First Nations and Settlers

Reconciliation is proving to be a challenge to achieve. Many are not participating in the Calls to Action. The apathy results in the status quo, as seen In the following videos.

Viewing Assignment 4

View the following three videos on the relationships between indigenous communities and their neighbouring settler communities:

https://gem.cbc.ca/media/mashkawi-manidoo-bimaadiziwin-spirit-to-soar/s01e01?cmp=pov-pareto-doc

https://gem.cbc.ca/media/cbc-docs-pov/s04e01?cmp=pov-pareto-docs

https://gem.cbc.ca/media/firsthand/s02e09?cmp=pov-pareto-docs

Questions

- What was the main objective of the Indian Act of 1876?

- What was the primary purpose of the Residential School System?

- Was the 1969 White Paper constitutional?

- What major shift in the relationship with the First Nations did the Government of Canada take after the 1985 Indian Act Revision?

- Do you think the 94 steps of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will bring reconciliation?

- If not, what more needs to happen to see reconciliation come to fruition?

[1] David D Plain, The Plains of Aamjiwnaang, Trafford Publishing: Victoria, B.C. 2007 p123

[2] The Canadian Encyclopedia https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/duncan-campbell-scott last accessed February 9, 2022.