Module 4: Treaties & Resistance

Lesson 4.2: Treaties – Expressions of Peace and Friendship

Introduction

All nations are governed by treaties. Most often when we think of treaties we think of those that end wars – peace treaties – but they can be for trade purposes (as just a few years ago when the United States, Mexico, and Canada signed a new trade agreement), basic diplomatic matters such as recognition of national boundaries, or more complex international agreements on everything from environmental standards to limits on nuclear weapons. While covering quite different topics, treaties impose the same forms of legal obligations on all the signatories. As treaties signed between recognised national groups, Canada’s historic treaties with Indigenous peoples are no different.

Between 1678 and 1761, numerous treaties were signed between Great Britain, or its colonial governments in Boston and Halifax, and the Wabanaki peoples of the northeast. They are called Peace and Friendship Treaties. For the British, the treaties sought to pacify the Mi’kmaq and their Wabanaki allies – all traditional allies of the French – and prevent them from participating in an ongoing series of wars over territory in what is today termed eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. For the Mi’kmaq, the treaties were aimed at restraining British settlers’ incursions into Mi’kma’ki.

The most important of these treaties came about in the 1690s and 1720s, decades marked by a series of wars across the northeast. The biggest of these wars is most commonly called King Philip’s War; it was probably the most destructive war of the colonial era. That war ended in 1678, and peace treaties were signed. But as historian Lisa Brooks explains, the colonial land grabs that sparked that war continued, as the New England colonies expanded north along the coast and inland to the west. That expansion also brought the British colonies into conflict with the French colonies to the north (Canada) and the northeast (Acadia). Much of that same period was also marked by ongoing wars in western Europe between its two great powers, Britain and France, and these spilled over into northeastern North America. Thus, the land between British and French settlements, whether by land or by sea, was often a war zone. And that war zone was Wabanaki territory.

In one of those later wars, the one which European history calls the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14), British and New England forces captured Port Royal, the administrative capital of Acadia. Britain was awarded Acadia in the subsequent peace treaty (Utrecht). As we already saw in Lesson 1.2, that simple statement was much messier on the ground than on paper. But amid a lot of blurred lines, two things were indisputable. First, that the French Catholic Acadians were now, at least nominally, ruled by Britain. (We’ll come back to that issue in Module 5). Second, “Acadia,” as we’ve seen, was really a series of small agricultural settlements and even smaller fishing settlements. The territory labelled “Acadie” on European maps was still controlled by the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and other Wabanaki peoples, and British control over Acadie was weak. That meant that if Britain wanted to maintain its very tenuous hold on the peninsula, it would need to either defeat the Mi’kmaq militarily, or negotiate treaties with them.

We’ll examine two of the actual treaties, one signed in 1725 and another in 1752, and try to understand exactly what they say. The treaties are fundamentally similar, though not identical. They were signed in different times, by different peoples, under different circumstances. We can, however, see some common patterns and some common principles. And legally, the treaties are all still in force. So our question then becomes, what does that mean?

We’ll also examine a set of records related to the 1725 treaty and explore the context of the 18th-century colonial-Indigenous treaties, as well as the process of making them. We’ll use Voyant Tools to explore the broader context.

Historians are limited by the sources available to them. Most of the documents we’re reading in this lesson come from two sets of records published by archives in Maine and Nova Scotia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Examining the entire corpus of records, not just the ones we’ve identified as relevant, offers insights into both the broader historical context and the biases of colonial archives.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify the nature of the agreements formed by Wabanaki-British treaties.

- Describe how the historical context alters/confirms our understanding of those treaties.

- Describe the relationship between Wabanaki-British diplomacy and settler colonialism.

- Understand the manner by which the Wabanki confederacy organized their diplomacy.

Technologies used for this lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

- Voyant Tools is a web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts. It is a scholarly project that is designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public. Read more about Voyant Tools.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in lesson 1.1 and map making in lesson 2.1. In this lesson, you will need to use the StoryMaps feature in your ArcGIS public account. To prepare you for making your story map, read through this tutorial before beginning this lesson.

Instructions

Documents

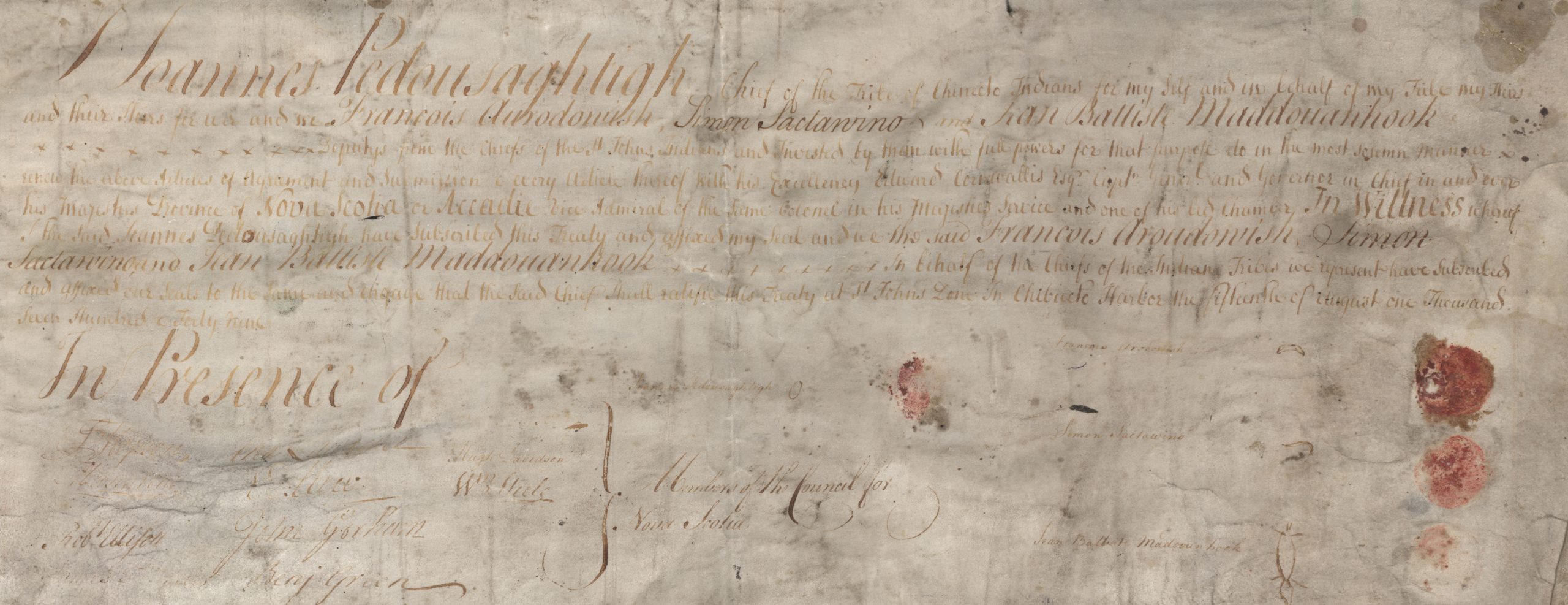

1. “Treaty of Boston,” 1725.

-

- For Britain and France, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) ended Queen Anne’s War, but it did nothing to prevent British settlers from pushing further into Wabanaki territory. For another ten years, British settlers aggressively annexed land into what is today the state of Maine. Further north, in Nova Scotia, the British struggled to assert control of the territory they now claimed there. The Wabanaki were amenable to negotiations, but also resisted armed efforts to take their land. Realising their limited capacity to protect their own people, the British pursued negotiations beginning around 1722. The Treaty of Boston (1725) was the outcome of those negotiations.

- Treaty of Boston [link opens in new window]

2. “Treaty or Articles of Peace and Friendship, Renewed between His Excellency Peregrine Thomas Hopson Esquire Captain General and Governor in Chief in and over His Majesty’s Province of Nova Scotia or Acadie,” 1752.

-

- After the British-French Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and Wabanaki-British Treaty of Boston (1725), two major events altered the situation in Mi’kma’ki/Nova Scotia.

- The European War of the Austrian Succession spread to the colonies, where it’s known as King George’s War (1744-48). Though formally speaking, little changed as a result of that war, it made it clear to British and Mi’kmaw leaders alike that the peace of 1725 was no longer effective.

- The British sought to counter the French fortress of Louisbourg. In 1749, therefore, Halifax was founded as a garrisoned port city that would solidify British presence on the mainland of Nova Scotia and allow them better access to the fishing banks and shipping lanes off the coast. As we saw in our last lesson, the Mi’kmaq saw this act as an invasion of their territory.

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship, 1752 [link opens in new window]

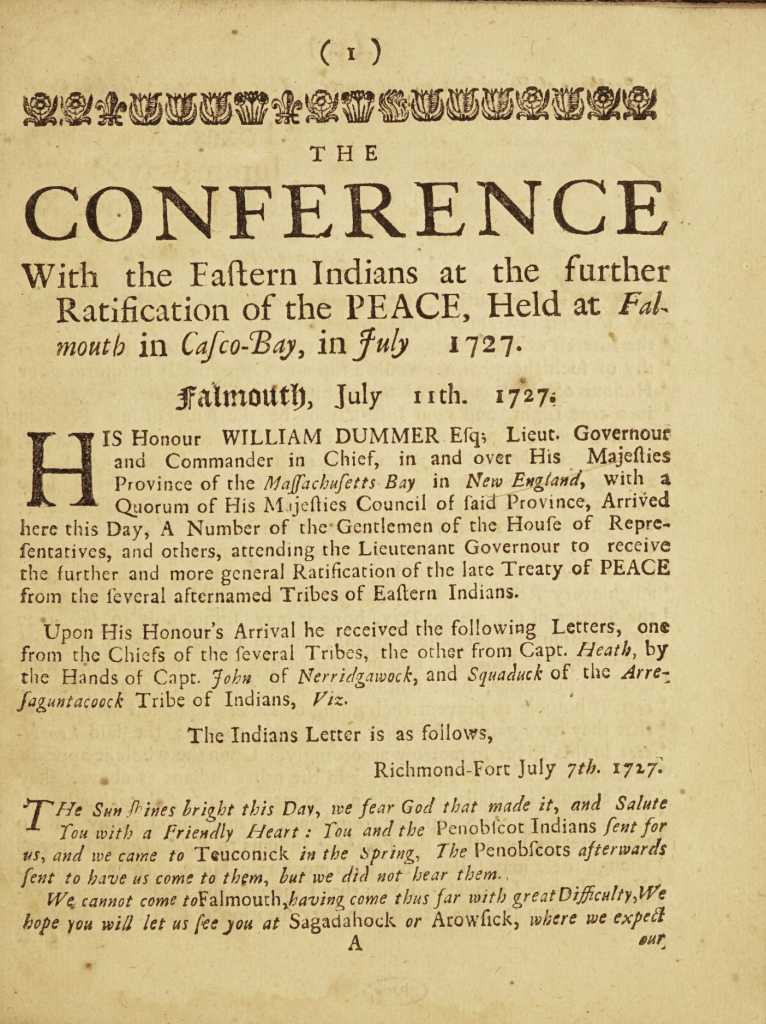

3. “Reports of Council regarding negotiations with Wabanaki, Assembly of Massachusetts,” November 1725.

-

- The period following Utrecht saw continued confrontations between the British and various Indigenous peoples north and east of Massachusetts. Here we see the outcome of several years of diplomatic efforts to bring together the “eastern Indians” – the Wabanaki – and the British in negotiations at Casco Bay, just north of Boston. These negotiations were complex and while led by Penobscot leaders, we can see evidence of the broader Wabenaki presence.

- In 1725, Nova Scotia’s government consisted of only a few appointed officials, but officials in Boston and London believed they needed stronger guarantees of peace with the Mi’kmaq. As a result, the following year, the council in Annapolis Royal [the old French capital of Port-Royale] sought a ratification directly with the Mi’kmaw leadership.

- Massachusetts Assembly reports [link opens in new window]