Module 5: Remaking Mi’kma’ki, Acadie, & Nova Scotia

Lesson 5.2: Making “Nova Scotia”

Introduction

Having expelled most Acadian settlers in 1755 and 1758 and having negotiated a series of treaties with the Mi’kmaw and Wabanaki nations, Britain and its colonial officials in Boston and Halifax set about efforts to remake the colony as an Anglo-American place. From a British-New England perspective, they now had a blank slate upon which they could write as they pleased. Part of that process occurred through measured state-led endeavours to administer settlement and proper government; part of it was a land grab, a period which one notable historian describes as a series of “wild schemes, conflicting claims, and unfulfillable promises that actually hindered the colony’s recovery from the devastations of war and depopulation” [Anderson, CoW, 523]. In many ways it was both.

Though small compared to the rapidly growing New England colonies, Acadians had built a series of successful agricultural settlements. Acadian farms regularly produced surpluses of cattle and wheat that found a ready market in Annapolis Royal and Boston, and from a British perspective, more problematically in Louisbourg and Quebec. That made these lands attractive. Knowledge of this productivity was widespread and in fact was one of the reasons the British never pushed hard for the removal of the Acadians after 1713: they knew Acadian crops were vital supports for the feeding the fishery and the military. As we’ve seen, however, that thinking changed, and now imperial and colonial planners set about putting a British stamp on Acadie/Mi’kma’ki.

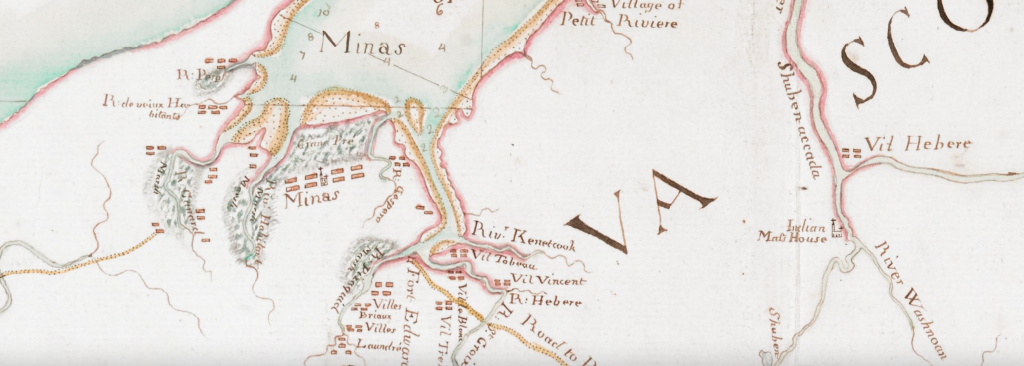

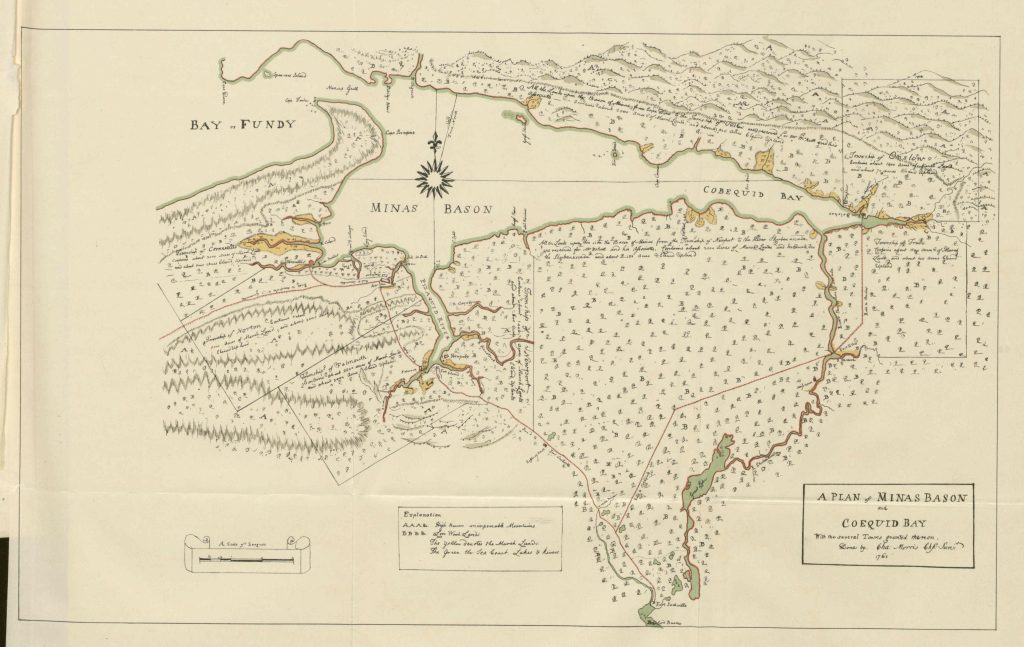

One of the most important of these British planners was Charles Morris, a Boston-born army officer who was stationed at Annapolis Royal, and in 1750 was appointed Crown surveyor for the province. His reports and maps outline many of the specific actions that would unfold over the next decade, as well as the general views of British officials in acquired territories. Morris was one of the architects of the expulsion of the Acadians. In a series of reports written between 1749 and 1755, he outlined various schemes for marginalising the Acadians (mostly swamping them with British, New England, Swiss and German Protestant settlers), and renaming places: the Acadian village of Beaubassin became Sackville; the Mi’kmaw settlement of Mirligueche became Lunenburg, and they would be populated not with “Indians” and French Catholics, but European Protestants. He quickly shifted his position, however, to simply removing the French Catholics who had farmed those lands for three, sometimes four generations. His 1755 map of the French settlements was very much a tool for identifying the major and minor Acadian settlements. By that point he had become one of the most influential figures in Boston and Halifax. As Surveyor-General he had become the most knowledgeable Briton alive on the geography of the province; that knowledge would now allow him to be the principal architect remaking Acadie into Nova Scotia.

This lesson asks you to examine texts and maps related to planning Nova Scotia after the Seven Years War. In Acadie/Mi’kma’ki the language, and indeed the story itself, is tricky because it was not simply European colonizers displacing Indigenous peoples, but of one set of European colonizers dispossessing not only Indigenous peoples but also another set of European colonizers. That latter group, the Acadians, was not an army, but several thousand farmers who had occupied their lands for generations. The relationship between the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq was not as easy a coexistence as is often presented in the mythic description of Acadia, but at minimum the two peoples had spent decades sharing space without large-scale conflict. They had also come to share a common enemy: the British. We can’t explore that Acadian-Mi’kmaq relationship in this course, but we can explore how the Anglo-Americans saw the two groups, and how they planned for their removal.

These documents will allow you to see the strategies employed by the mapmakers, their goals, and how the maps were designed to both reflect existing policy and to envision new approaches and possibilities. In exploring the production of maps, this exercise will enable you to better understand the language and strategy of mapping and its role in turning Acadie/Mi’kma’ki into British Nova Scotia.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Evaluate a map beyond its content, and identify a strategy or argument.

- Explain the British strategy for remaking Acadie as British Nova Scotia.

- Trace the imprinting of Nova Scotia onto Acadie and Mi’kma’ki.

Technologies Used in this Lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in lesson 1.1 and map making in lesson 2.1.

Instructions

Documents

1. Charles Morris, “A Chart of the Sea Coasts of the Peninsula of Nova Scotia,” 1755. Source: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

- As noted above, Morris was the Crown Surveyor of Nova Scotia, working there after 1748. Exceptionally knowledgeable, he was politically influential and powerful as British and New England officials sought to make Nova Scotia a truly British colony. This map was made early in 1755, and is undoubtedly the best map we have of Acadian settlements prior to what Acadians still call “le Grand Dérangement” [the great upheaval]. But there are indications of change already in view. Some features on the map suggest Acadian lives in turmoil; can you see indications of the political instability they were facing even in this moment before le Grand Dérangement?

- Open Morris, Chart of the Seacoasts [link opens in new window]

2. Charles Morris, “A chart of the peninsula of Nova Scotia,” [1761], Source: Library of Congress.

- Once its people were expelled, “Acadie” became a very different place. In this second Charles Morris map from 1761, what are the changes you see when compared to the 1755 version?

- Open Morris, Chart of the Peninsula [link opens in new window]

3. “An Act for the Quieting of Possessions to the Protestant Grantees of the Lands formerly occuppied [sic] by the French Inhabitants, and for preventing vexatious Actions relating to the same.” At the General Assembly of the Province of Nova Scotia, August 1759, 33 George II – Chapter 3 (Session 1). Source: British North American Legislative Database, University of New Brunswick.

- Nova Scotia’s movement from battleground to colony of settlement required a dramatic shift in the priorities of government. Why, after the expulsions of the Acadian population in 1755 and 1758, would British colonial assemblymen need to pass legislation such as this?

- Open Quieting Possessions [link opens in new window]

4. [Charles Morris], “Description and State of the New Settlements in Nova Scotia in 1761 by the Crown Surveyor [1761],” Report on Canadian Archives, 1904 (Ottawa, Dept of Agriculture, 1904), 289-301.

- No one in British North America knew early Nova Scotia’s geography as well as Charles Morris, but this report is not an objective compendium of information. Like the maps, it has a clear orientation, and a purpose. What did Morris view as progress? What did he point to as factors holding back these communities? Were they, in fact, new settlements?

- Open Morris, Description of the New Settlements [link opens in new window]

5. Documents relating to the settlement of Falmouth, Nova Scotia, 1760 and 1763.

- Very few British or New England settlers immigrated to Nova Scotia after Britain formally acquired the colony in 1713. But after 1755, their numbers increased dramatically. What had changed? Does this rush suggest another dimension of Britain’s desire to control Mi’kma’ki? Where is Falmouth? What’s a sloop? What do these details suggest about the movement of peoples? Compare these reports with what Morris reported in 1761.

- Open List of Settlers brought from Newport in Rhode Island to Falmouth in the Sloop Sally [link opens in new window]