Module 5: Remaking Mi’kma’ki, Acadie, & Nova Scotia

Lesson 5.1: Le Grand Dérangement

Introduction

The founding of Halifax marked a radical turn for Mi’kma’ki and Acadie. Before 1749, the British presence on the land had been fairly marginal. Though they had begun to push beyond the fortifications at Annapolis Royal, for the most part the region was one defined by the Mi’kmaq and their Acadian neighbours. With the establishment of Halifax at Kjipuktuk in 1749, the British presence became much more ubiquitous and contested. Not only did Britain build a new fort there, but with this imperial investment, they also brought settlers in the hundreds. Alongside Halifax, the British also established German speaking Protestants at Lunenburg. All told, by 1755 there were as many as 5,000 British settlers now living in the colony.

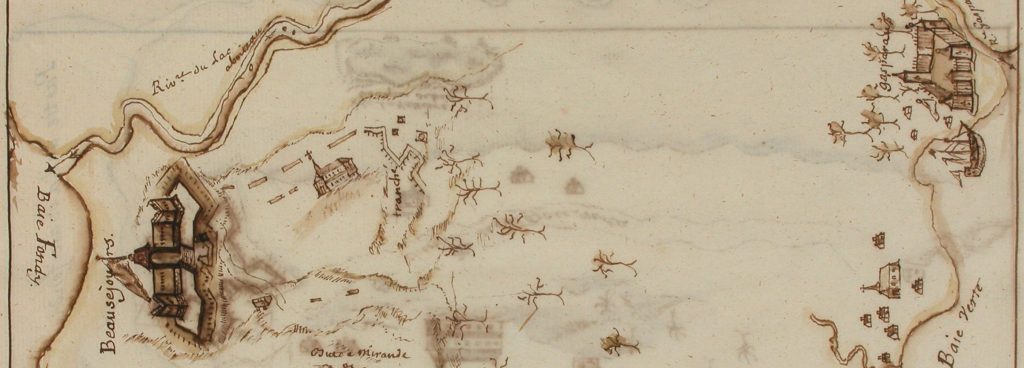

Halifax is emblematic of broader changes in how Europeans were thinking about empire. As imperial officials encountered growing challenges in managing overseas affairs, imperial policies began to change. There were two key consequences of these changes. First, as we saw with treaties, decisions were increasingly being made by people with neither a deep understanding of the local context nor on-the-ground relationships, making it easier to implement policies that might harm local communities. Second, both empires were now willing to invest in North America in unprecedented ways. For example, to protect its economic interests, in 1719, France built Louisbourg in Unama’kik, as well as several new fortifications in the Lower Great Lakes and along the Mississippi, connecting its colonies of Canada and Louisiana. France also built a new fort at Beaubassin in 1750, known as Fort Beausejour (depicted above).

These changes were part of a military contest that by 1749 had already brought considerable violence to the region. Though warfare really only arrived in the region in the later years of The War of Austrian Succession, its impact was significant and yielded significant casualties in Mi’kma’ki. The French, along with Mi’kmaw, Wabanaki, and Wendat allies, made two separate unsuccessful attacks on Annapolis Royal. In 1747, they had more success in a raid on a British encampment at Grand Pré. This victory was relatively insignificant, however, given that only the previous year, New Englanders had successfully captured Louisbourg. The French position in the region was weak.

With the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, peace returned in early 1748. The lesson learned on both sides, however, was that Mi’kma’ki needed to be militarized if either empire were to prevail. In addition to building at Beaubassin, France reinvested at Louisbourg, and fortified Baie Verte (Fort Gaspereaux) and the mouth of the Saint John River. The British, meanwhile, in addition to building Halifax, extended their military presence to Piziquid (Fort Edward) and Sackville, as well as into Beaubassin. By 1751, France’s Fort Beausejour lay only four kilometers across the Missaguash River from Britain’s Fort Lawrence.

Rather than bringing lasting peace, it is more accurate to say that the 1748 peace caused a pause in the fighting. By 1754, violence between Britain and France was renewed in the Ohio Country, territory between the Mississippi and Lake Erie. Shortly thereafter it sparked again in Mi’kma’ki; Beaubassin was the only place in the world where British and French fortifications were located in such close proximity to each other.

Furthermore, despite the growing British Protestant population in Halifax and Lunenburg, the French Catholic Acadian population had reached over 15,000 people. British officials with limited relationships with either the Acadians or Mi’kmaq feared that, with the French military so close, those groups would be encouraged to rise up against the British. With a large population of New Englanders, many of whom were upset that Britain had returned Louisbourg to France, British officials at Halifax and in Boston planned to seize Fort Beausejour.

The attack came in June 1755 and was over almost as quickly as it had begun. The British capture of Fort Beausejour, however, was only the beginning. In addition to removing the French military threat, British and New England officials quickly sought to solve the Acadian problem that had long been a thorn in the colony’s side.

From the moment of Britain’s initial occupation of the fort at Annapolis in 1710, tensions over the loyalty of the Acadian population threatened the region’s stability. At issue was whether this French Catholic population would agree to take an oath of allegiance to the British crown. Though the question had festered for decades, British administrators had been willing to compromise until the new regime arrived in 1749. The new administrators had limited understanding of local experience, and the issue of loyalty flared up again in the 1750s – specifically in the weeks after Beausejour fell. On 28 July, 1755, British officials decided to deport the entire Acadian community. By 1763, when the deportation wound down, over 15,000 people had been forcibly removed to Britain’s American colonies, England, France, Louisiana, and the Caribbean.

This module will introduce you to several accounts written at Beaubassin during the 1750s. Using the digital tools we have drawn upon in earlier modules, you will develop an understanding of the circumstances that led to the Acadian Deportation.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Explain the causes and consequences of the Acadian Deportation.

- Understand the on-the-ground situation that led to the capture of Fort Beausejour.

- Use distant reading techniques to compare and contrast accounts of the events that took place at Beaubassin in 1755.

Technologies used for this lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

- Voyant Tools is a web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts. It is a scholarly project that is designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public. Read more about Voyant Tools.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in lesson 1.1 and map making in lesson 2.1. In this lesson, you will need to use the StoryMaps feature in your ArcGIS public account. To prepare you for making your story map, read through this tutorial before beginning this lesson.

Instructions

Documents

- “Journal of Colonel John Winslow of the Provincial Troops, while engaged in the Siege of Fort Beausejour in the Summer and Autumn of 1755,” in T.B. Akins, ed., Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1869), pp. 141-230. (selections).

-

- John Winslow was a well established officer in the British Army. The grandchild and great-grandchild of governors of the Plymouth Colony, Winslow quickly rose up the ranks of the British military, serving in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Maine. In 1755, he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel, overseeing a regiment charged with supporting Charles Lawrence remove the French from the aspiring colony of Nova Scotia. In June of that year, he was stationed at Fort Lawrence and once the French threat had ended there, he moved to Grand Pre, where he oversaw the removal of over 1,500 Acadians to Britain’s other American colonies.

- Winslow Journal (selections) [Opens in a new tab]

- Read the whole journal here [Opens in a new tab]

-

-

“Lieut.-Colonel Monkton’s Journal of 1755” in John Clarence Webster, ed., The Forts of Chignecto: A Study of the Eighteenth Century Conflict between France and Great Britain in Acadia (Published by the Author, 1930).

-

- Robert Monckton was a British aristocrat from Yorkshire. Joining the British Army at age 15, Monckton served in Europe before being posted to Nova Scotia to command Fort Lawrence in 1752. A year later, he joined the Nova Scotia Council. In June 1755, he oversaw the capture of Forts Beauséjour and Gaspereaux, and by end of year was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia.

- Monkton Journal [Opens in a new tab]

-

-

“Journal of Abijah Willard of Lancaster, Mass.,” in J Clarence Webster, ed., Collections of the New Brunswick Historical Society no. 13 (Saint John, 1930).

-

- Abijah Willard was a captain in the New England Provincial Regiment that attacked Fort Beausejour in June 1755. Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, Willard followed a family tradition of joining the provincial military. In addition to fighting in the siege of Beausejour, Willard also participated in the 1745 capture of Louisbourg. He remained active in the British military throughout the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, settling in Saint John at the conclusion of the later conflict.

- Journal of Abijah Willard [Opens in a new tab]

- The original can be found at the Huntington Library. [Opens in a new tab]

-

-

[Charles Morris], Remarks concerning the settlement of Nova Scotia. 1 (Charles Morris, 1753.) Remarks concerning the settlement of Nova Scotia. 1 (Charles Morris, 1753.) Source: Le Canada-français: Documents inédits (Sur l’Acadie ), (Québec :Université Laval,1888), 97-101.

-

- The son of a prominent New England family, Charles Morris was the surveyor-general of Nova Scotia. He arrived in the province shortly after the founding of Halifax. By 1755 he had been appointed to the Legislative Council, marking him as one of most powerful people in the colony’s first decades. As provincial surveyor, he travelled the region mapping townships and settlements before and after the expulsion, smoothing the way for New England and other non-Catholic settlers to build the colony. No one, therefore, had a better sense of the social and political geography of the colony. His views were very persuasive.

- Report of Charles Morris, 1753 [Opens in new tab]

-

-

“Governor Lawrence to Col. Monkton, Halifax, 31 July, 1755 to Charles Lawrence and response.” In Thomas B. Akins, Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax, (C. Annand, 1869), pp. 267-269

-

Résumé of Imprisoned Beaubassin Inhabitants to Monkton in Leicester Harmsworth ed. The Northcliffe Collection (Ottawa, F. A. Acland, 1936), pp. 33-34

-

“Translation of the Pisiquid, Menis (Mines) and River Canard deputies’ address at a council held at the Governor’s house in Halifax on Friday July 28th 1755 to Charles Lawrence and response.” In Thomas B. Akins, Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax, (C. Annand, 1869), pp. 263-267.

-

“Translation of the Memorial from the French inhabitants of Annapolis River presented at a council held at the Governor’s house in Halifax on Friday July 25th 1755 to Charles Lawrence and response.” In Thomas B. Akins, Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax, (C. Annand, 1869), pp. 261-262.

-

A Large and Particular Plan of Shegnekto Bay and the Circumjacent Country with the Forts and Settlements of the French till dispossessed by the English in June 1755. Drawn on the Spot by an Officer.