Module 4: Treaties & Resistance

Lesson 4.1: Voices of Resistance

Introduction

After decades of back-and-forth between competing French and English claims to Mi’kma’ki, the European geopolitical context changed in 1713. In that year, and 5,000 kilometres away in the Netherlands, European diplomats came to an agreement that ended the War of Spanish Succession. Though there were no Indigenous diplomats at the meetings that brought about the peace, the resulting Treaty of Utrecht had lasting repercussions in Mi’kma’ki. Just three years prior, the British had captured Port Royal (for the fourth time) and, at Utrecht, France and Britain agreed to a division of territory that effectively ripped Mi’kma’ki in two.

For the first time since Europeans set foot on Mi’kmaw Homelands, Mi’kma’ki was divided between French and British claims to their Land. The Mi’kmaw regions of Kespukwitk, Sipekne’katik, Eskikewa’kik, and Piktuk were claimed by Britain, while Unama’kik, Epekwitk, Siknikt, and Kespe’k were claimed by France. Despite European agreement about this new geopolitical situation, no one informed the Mi’kmaq. When they learned what France and Britain had agreed upon, they were shocked. By what right had the King of France ceded Mi’kma’ki to Britain, they asked.

In this lesson, we will listen to the Mi’kmaq and their Wabanaki allies and see how they responded to this type of unilateral European action. Though we can assume that there might have been similar tensions before 1713, the small-scale nature of the European presence in Mi’kma’ki meant that evidence of this type of opposition is difficult to find. After this period, and with almost every extension of the French or British occupation of Mi’kma’ki, the Mi’kmaq and their allies made their position clear. Listening to their words helps us understand the structures of power at work in the region over the course of the 18th century. In their documents we read about how these people envisioned their relationships with the European newcomers, with each other, and with the Land. Though each document was penned by French allies – and have sometimes been dismissed because of this – we see these sources as some of the clearest and most direct articulations of contemporary Indigenous perspectives available to us.

To better understand each of these documents, we are going to return to ArcGIS and ask you to build a story map that helps interpret how the Mi’kmaq and Wabanaki responded to the Treaty of Utrecht and subsequent British encroachment into Mi’kma’ki. The collected documents will take you from Utrecht and its immediate aftermath through to the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify the key changes brought about by the Treaty of Utrecht.

- Discuss Mi’kmaw and Wabanaki perspectives on their territory and political relationship to European empire.

- Build a basic story map using ArcGIS online.

Technologies used for this lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

- Voyant Tools is a web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts. It is a scholarly project that is designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public. Read more about Voyant Tools.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in Lesson 1.1. In the fourth activity in this lesson, you will extend your learning by using the “sketch” function to make a basic map. To complete this activity, you will need to create a public account on ArcGIS’s online platform. We have also created a tutorial worksheet for you, which will help you begin to use ArcGIS.

Instructions

Documents

- Lettre des Abénaquis au roi de France pour obtenir son appui alors que les Anglais cherchent à s’emparer de leurs terres, vers 1715. C11A-1 fol. 266-267v.

-

- Possibly written by the Jesuit Joseph Aubery, who worked among the Abenaki at Odanak, this bilingual document was written in both Wabanaki and French. Though it uses the language of Catholicism, pay careful attention to the guiding principles that it develops related to imperial entrenchments, Land, and warfare.

- Open 1715 Translation [Opens in a new window]

-

-

Antoine and Pierre Couaret to Philipps, 2 Oct 1720, CO217-3, f. 155.

-

- Antoine and Pierre Couaret were two Mi’kmaw leaders from Sipekne’katik, known by the 1720s to the French and English as Minas. Their letter to Nova Scotia Governor Richard Philipps is one of the first written expressions of Mi’kmaw resistance to imperial intrusions in the archival record; it was penned shortly after several Mi’kmaw men had captured John Alden’s trading vessel in the Minas Basin.

- Open Couaret letter – 1720 [Opens in a new window]

-

-

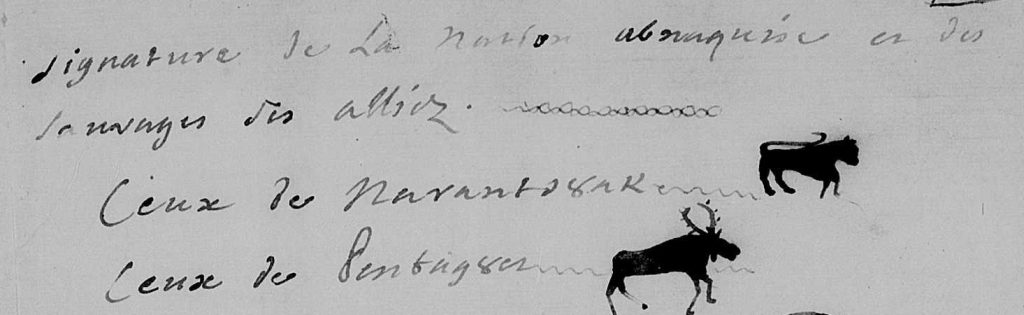

Grand Captaine des Anglois… , 28 July 1721, UKNA CO 5, vol. 869, fol. 106-107

-

- This letter is similar to Document 1. Rather than addressing their concerns to the French though, here the letter is addressed to the British governor at Boston, Samuel Shute. Though sharing some similar messages, the document also claims to represent a broader polity including Wabanaki nations, but also their Mi’kmaw allies as well as allies from the St. Lawrence River. In addition to circulating locally within the region, the letter’s contents were also printed in The Weekly Journal: or British Gazetteer, a British newspaper.

- Open Great Captain of the English – 1721 [Opens in a new window]

-

-

Lettre de M. Maillard à l’abbé Dufau et un recommendation pour une promotion à DuCaubet, 1749, Musée de la civilisation, fonds d’archives du Séminaire de Québec, Lettres P, no. 66, https://collections.mcq.org/objets/270888.

-

- Though penned by the Catholic missionary Pierre Maillard, this letter expresses Mi’kmaw views on the arrival of British troops at Halifax at Kjipuktuk (Halifax). It was sent to Edward Cornwallis shortly after his appointment as Governor of Nova Scotia. Much like Joseph Aubery at Odanak, Maillard spent much of his time in Mi’kma’ki learning the Mi’kmaw language, making him a pivotal intermediary between Mi’kmaq and British officials.

- Open Maillard to Dufau – 1749 [Opens in a new window]

-

-

At a council holden at the Governor’s house on Monday, the 9th day of September 1754, T.B. Akins, Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1869), 216. This is from a translated letter sent by Le Loutre. See also Copie de la lettre de M. l’abbé Le Loutre, prêtre missionnaire des sauvages à l’Acadie, à M. Lawrence, commandant en chef de la province d’Acadie à Halifax, 26 Aug 1754, C11D-8, f. 209-210.

-

-

- Abbe Jean-Louis Le Loutre was a contemporary of Pierre Maillard’s. Where Maillard served the Mi’kmaq around Unama’kik, Le Loutre was more active in Sipekne’katik and Siknikt. Though both missionaries served in important diplomatic roles during this period, Le Loutre took a much more active role in supporting France’s war efforts during the 1740s and 1750s.

- At a council holden at the Governor – 1754 [Opens in a new window]

-