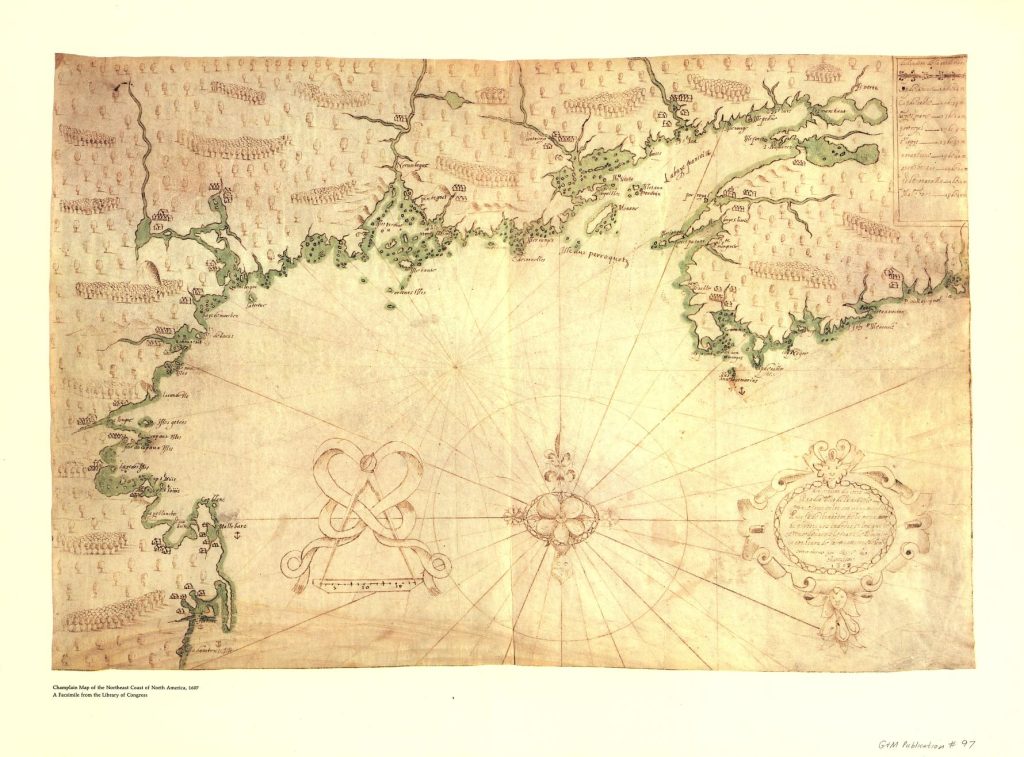

Module 3: Missionaries and Captivity Narratives

Lesson 3.2: Captivity Narratives

Introduction

As you have seen in lesson 3.1, missionaries’ letters inform us of the social dynamics that prevailed in Mi’kma’ki. As privileged witnesses, the missionaries provide glimpses of the daily life of the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqiyik, and the Abenakis with whom they had to share their lives. The letters illustrate the many difficulties the missionaries faced while trying to adapt to life among people whose visions of the world were not shaped by western and Christian tenets. While distorted by eurocentric lenses, their testimonies serve as valuable ethnographic documents.

In lesson 3.2, you will access other types of documents that provide valuable information on the interactions between the Indigenous, French, and English populations in Mi’kma’ki: captivity narratives and deeds of sale for enslaved people.

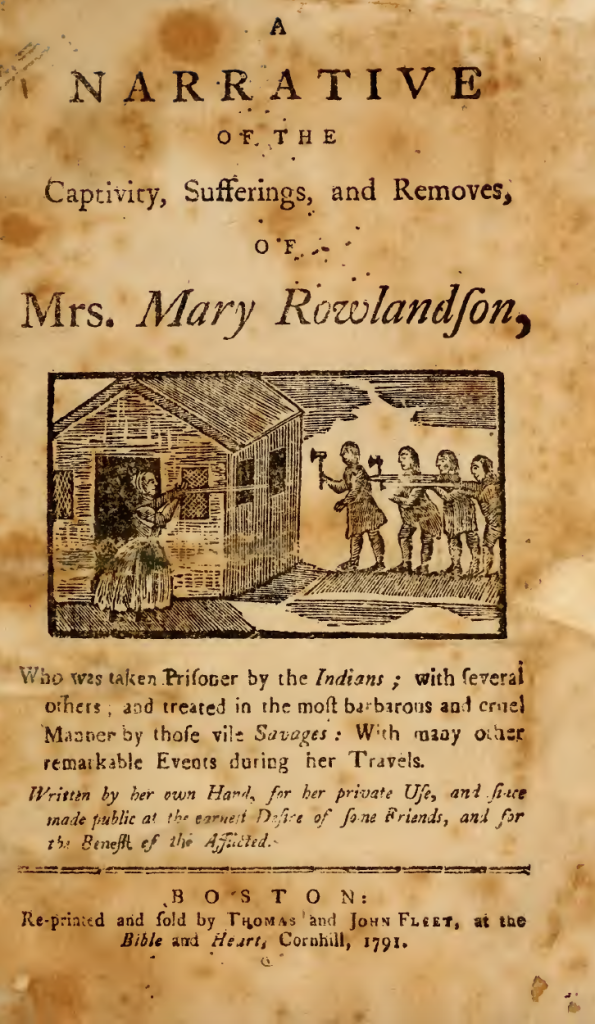

Captivity narratives were published accounts of settlers who were captured in wars or raids and held by French or Indigenous peoples. They were kept for ransom or to be used in prisoner exchanges during diplomatic negotiations. These stories were very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, to the point of becoming a literary genre. Filled with drama, action, and emotion, some captivity narratives read like adventure stories, while others are reminiscent of religious pilgrimages. For New England colonists, narratives like those of Rowlandson and Gyles were set in a familiar world, a violent environment torn by conflicts and wars, and where being taken as a prisoner was a common risk. Those stories served to demonstrate that people who had returned from captivity had been able to keep their moral integrity, even after living among those they considered uncivilized.

Mary Rowlandson and her three children were captured in February 1676 by a group of Algonquian-speaking Wampanoags, Narragansetts, and Nipmucs during the conflict known as King Philip’s war, or Metacom’s war (1675-1676), one of the bloodiest conflicts in American history. The hostilities were sparked by accumulate frustrations provoked by the relentless encroachment of English newcomers into Indigenous land. Both sides committed atrocities, and the relationship between English settlers and Indigenous peoples was deeply affected.

While none of the Wabanaki nations participated in King Philip’s War, they suffered its repercussions. British settlers’ hostility extended to all northeastern Indigenous nations, drawing few distinctions between the Indigenous nations of the northeast, affecting their relations with the Mi’kmaq and the Wolastoqiyik as well. Conflicts with New England settlements pushing further north, and with New England fishers along the coast of Nova Scotia, meant that settlers saw the Mi’kmaq as enemies requiring annihilation. That contributed to decades of ongoing conflict – and occasional open warfare – stretching far north into Maine and Nova Scotia.

John Gyles’ captivity was also part this context of war and tension between New England, New France, and the Wabanaki Confederacy. In August 1689, Gyles, aged nine, was captured by a party of Wolastoqiyik in Pemaquid, Maine. His mother, sisters, and brothers suffered the same fate, while his father was killed during the attack.

Rowlandson spent eleven weeks with her captors, relocating multiple times until she was ransomed later that spring. John Gyles’ captivity with the Wolastoqiyik lasted six years, at which point he was sold to a French settler. He spent an additional three years in Acadie before eventually returning to Boston as a free man.

[You’ll encounter Gyles again in Module 4, as a translator in British-Wabanaki treaty negotiations during the 1710s and 1720s.]

We can imagine how traumatizing these experiences were, and how they affected the hostages’ perceptions of their captors. Rowlandson’s youngest child died in her arms. Her other two children were separated from her. She suffered from cold and hunger. While Gyles survived physical torments, he saw his brother tortured to death. As Puritans, the notion of being incorporated into an Indigenous society – a Catholic one, no less – made them dread losing their “Englishness” and their souls as much as they feared losing their lives. To different degrees, their faith in God and their hopes of future ransom and return to their people helped them to survive their ordeals.

Despite the hostages having privileged access to the daily life of their captors, their captivity narratives inform us more about the lenses through which they translated their experiences, than about the communities in which they were held. Having been forced into participation in the lifestyles of those whom they considered to be uncivilized people, their accounts gave reassurance that even once taken, one could return – that redemption was possible even after events that they perceived as God’s punishment for sinners.

Their testimonies also showed readers that captives could retain their identities and not be permanently changed by exposure to those who were commonly depicted as cruel and barbarous. The captives’ survival of their ordeals, the dramatic renditions amplified with descriptions of “savage Indians,” offered New Englanders a sense that people of faith – such as themselves – could endure in this dangerous world. The captives, and by extension the readers of captivity narratives, were exemplars of good Christians overcoming the dangers posed by “savages” and Catholics.

Enslavement was another form of captivity experienced in the Americas. In the West Indies, enslaved labourers were essential to the operation of the lucrative plantations producing sugar cane. In Acadie, however, the situation for enslaved people was different. The most important forms of labour – on farms, in the fishery and the fur trade – were undertaken by colonists and free Indigenous people, while enslaved people were primarily forced into domestic work. The men took care of the gardens and the outside chores, while the women were responsible for the household chores and cared for the children. They contributed to the success of their owners’ households, and their presence in those households was a sign of high status.

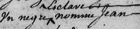

In Canada, the majority of enslaved people were Panis, a generic term for Indigenous slaves. While there were some Panis in Acadie, as a result of the close commercial connection between the French colony, New England, and the West Indies, most enslaved people in Acadie were of African descent. Treated as merchandise or commodities, they were part of commercial transactions between the colonies. These enslaved peoples were sold in for money or bartered for goods, and transferred from one place to another without consent.

Unlike Rowlandson and Gyles, none of those enslaved in Acadie wrote testimonies about their lives in this oppressive system. Their voices remain silent. However, legal documents, deeds of sale, and records of inheritance can shed some light on the lives of those men, women, and children. In the documents included in this lesson, you will meet some of the enslaved people who were part of society in Acadie. Through the documents, you will learn the names their owners gave them, their ages, the financial value put on their persons, how they arrived in the region, and the identities of those involved in the transactions. However faintly drawn, portraits of Jean, Jacques, Tousaint, Catherine, Louise, and Baptiste emerge from these papers, and reveal themselves as active members of their community.

Note on terms used

In these captivity narratives, you will notice that both Rowlandson and Gyles refer to Indigenous women as ‘squaws.’ The term is an adaptation of an Algonquin word meaning woman, but it has become offensive thanks to usage that has demeaned and objectified Indigenous women.

The term ‘negro’ is another sensitive word. The Spanish first used it as an evolution from the Latin word ‘niger,’ which translates as ‘black.’ Like the other terms mentioned above, it was used as a pejorative way to amalgamate all people of African descent into one dehumanized group, and has strong racist connotations. In a similar way, the term ‘Panis,’ originally a reference to a specific Indigenous nation in Illinois, was applied to all enslaved Indigenous people in New France.

These are hurtful terms. Students are encouraged to use them only when necessary, and to do so cautiously and thoughtfully. We do not wish to replicate the harm, only to make clear their effect.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Compare and contrast the underlying themes of the captivity narratives using both close and distant reading.

- Recognize the diversity of the social fabric in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki.

- Use the arcGIS Online platform to illustrate that diversity.

Technologies used for this lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

- Voyant Tools is a web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts. It is a scholarly project that is designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public. Read more about Voyant Tools.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in Lesson 1.1. In the fourth activity in this lesson, you will extend your learning by using the “sketch” function to make a basic map. To complete this activity, you will need to create a public account on ArcGIS’s online platform. We have also created a tutorial worksheet for you, which will help you begin to use ArcGIS.

Instructions

Documents

Captivity Documents

-

- The soveraignty & goodness of God: together, with the faithfulness of his promises displayed: being a narrative of the captivity and restauration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson: commended by her, to all that desires to know the Lords doings to, and dealings with her: especially to her dear children and relations. (Cambridge, printed by Samuel Green, 1682).

Rowlandson divided her narrative into the twenty removes she was forced into by her captors. Each section describes the events that took place, as well as the emotions Rowlandson felt during each relocation. The excerpts we chose are the Fifth and Sixth removes, relocations which took place when the English army pursuing them was getting close. The narrative illustrates how Rowlandson’s emotions wavered between hope and despair throughout her ordeal, and how she found solace in her faith.

-

-

- Fifth and Sixth Removes: Excerpt from Mary White Rowlandson [Opens in new window]

- Whole document: Narrative of Mary White Rowlandson [Opens in new window]

-

Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, &c. in the captivity of John Gyles, Esq; commander of the garrison on St. George’s River. Written by himself. ; Eight lines in English from Homer’s Odyssey (Boston, in N.E.: Printed and sold by S. Kneeland and T. Green, in Queen-Street, over against the prison., MDCCXXXVI. [1736]).

-

Gyles’ Memoirs reads more like an adventure story. The excerpt we chose is the third chapter Of further Difficulties and Deliverances. While Gyles is still considered to be and treated as a captive, he participates in regular activities like hunting and fishing with some of his captors, and demonstrates an interesting level of personal agency.

-

-

-

- Chapter III, Of further Difficulties and Deliverances: Excerpt from John Gyles [Opens in new window]

- Whole document: Narrative of John Gyles [Opens in new window]

-

-

Slavery Documents

Note that the links below all open in new windows.

-

- On 27 April, 1753, a young boy named Jean, aged 11 years old, is sold in Louisbourg to Sr Joseph Bete to become his slave.

- On 11 October, 1757, the enslaved Jacques, just arriving from Martinique, is sold to Mr Pierre de la Croix in Louisbourg.

- On 28 December, 1753, the enslaved Tousaint, a baker by trade, is auctioned in Louisbourg with specific conditions.

- On 1 March, 1753, the Sr Cassaignoles agrees to sell his slave Catherine to Cupidon, who wants to marry her.

- No date, probably 1727, the enslaved Panis Louise is brought from Montreal to Louisbourg, to be sold to the innkeeper Jean Seigneur.

- On 1 October, 1749, in Louisbourg hospital, an enslaved man known as Baptiste is recognized by a group of city officials as a slave belonging to a religious congregation.

Further Reading