Module 3: Missionaries and Captivity Narratives

Lesson 3.1: Missionaries, Soldiers of God, Agents of the Empire

Introduction

Since the early days of Christianity, members of that religion have travelled the world to spread the word of their God, and to convince pagans and those they saw as infidels to embrace their faith. European arrival in the Americas opened up a new reservoir of souls to harvest, and stimulated the creation of “missions” across the newly-discovered continent.

Like the other Catholic powers, Spain and Portugal, France forged intricate connections between conversion and colonization in what they considered to be their civilizing mission. Once the colonial project took shape, the French monarch, referred to as “the Most Christian King,” quickly encouraged the conversion of the Indigenous peoples. Bringing the word of God to New France, they believed, would save souls. And, once the Indigenous peoples of the world joined the great Catholic family, they would be easier to control. It is important to recognize that identity and ‘otherness’ in the 17th century was not a question of race, but more one of allegiance. If you recognized the rule of the French King and the Pope, you were considered a French subject. And the number of subjects a ruler had reflected the magnitude of their power.

Members of different Catholic religious orders came to New France for a variety of purposes. Nuns devoted themselves to education and medical assistance. Missionary work, which often implied living with Indigenous people, was primarily a masculine activity. The first missionaries to arrive in Mi’kma’ki were members of the Recollect, Jesuit, and Capuchin orders. They were joined towards the end of the 17th century by secular priests, Sulpicians, and members of the Missions Étrangères. While the groups had different approaches, they were all dedicated to a common mission: the spiritual salvation of the Indigenous people through Christian conversion.

The first challenge they faced was to find an efficient way to convey the message of their God to non-sedentary populations whose languages they did not know. How could they introduce the gospel to people with whom they could barely communicate? The missionaries soon realized their only option was to learn the different languages. The best way to do that was to live with Indigenous groups. That in turn implied travelling with them, as the Mi’kmaq and the Wolastoqiyik were seasonally nomadic. While some priests remained in local parishes to serve European settlers, missionaries constantly moved from one settlement to another. Their hosts settled close to the sea during summer for their fishing activities, and moved inland in winter to hunt. The lifestyle was unfamiliar and often difficult, but it gave the missionaries the opportunity to create strong links with the Indigenous communities they were serving, and to observe their customs.

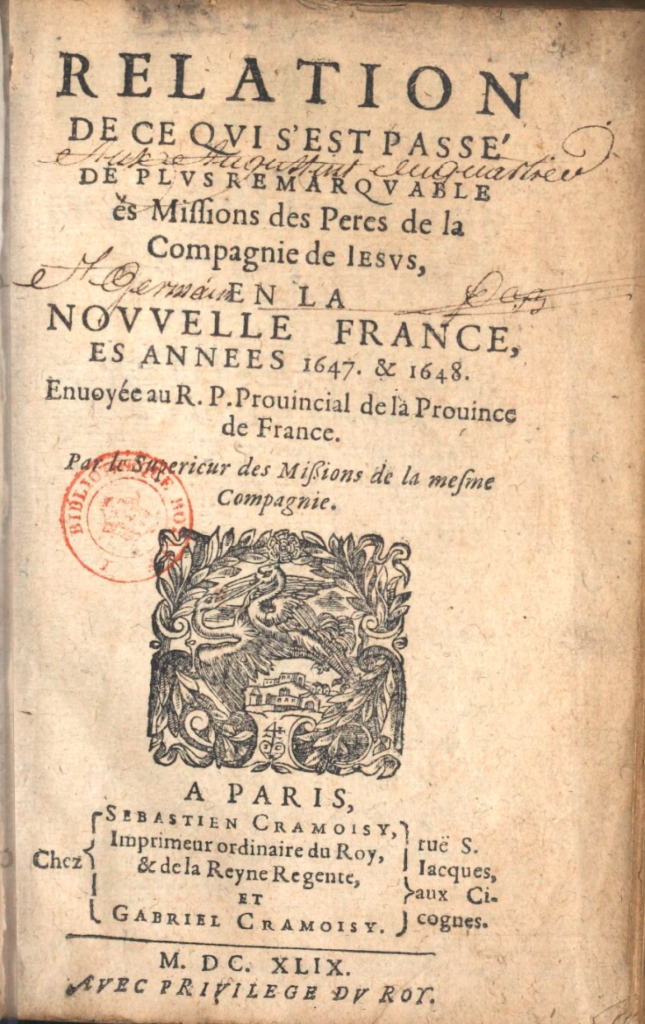

From their initial presence in Mi’kma’ki, missionaries had to provide regular reports to their superiors in France, Rome, and eventually Quebec. Some of those reports were published as Relations, although only after a certain amount of editing took place. These documents are valuable ethnographic works, even though the authors’ biases twist the image they present of the Indigenous communities.

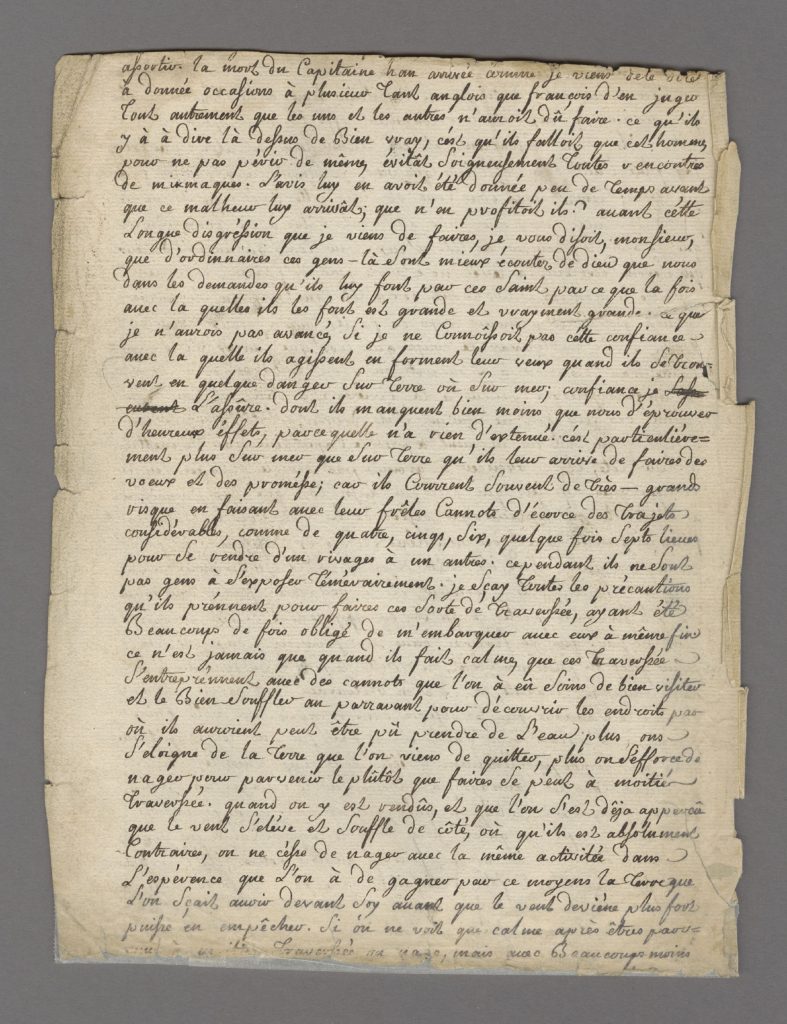

The missionaries’ correspondence, where they describe their experiences living among the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Abenaki, is another type of document that provides relevant information about life in Mi’kma’ki. The letters reveal not only the successes but also the difficulties and frustrations that the religious men faced in their efforts to carry out their mission.

Although the deep desire to save souls was the missionaries’ main incentive, the conversion of the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Abenakis to Catholicism was part of a broader imperial project. Providing new subjects for the King of France would help prevent the spread of the Protestant heresy in North America. Because of their close connection to the Indigenous nations of Mi’kma’ki, and the influence the missionaries could exert, French authorities used them to influence the Mi’kmaq away from alliances with the British. Meanwhile, the British saw the missionaries as a menace, and as the main reason behind Indigenous peoples’ and Acadian refusals to take an oath of allegiance.

The political situation affected the work of missionaries who actively participated in the French-English conflict, some even joining their Indigenous allies in war expeditions against the British. In Acadie, the missionaries served France as well as God.

In lesson 3.1, you will find relations and letters written by missionaries who stayed with different Indigenous communities throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. The first three documents are from Jesuits: Pierre Biard, Julien Perrault, and André Richard. The Jesuits were a well-organized religious order whose main objective was the evangelisation of infidels. They had missions in Europe, Asia, and South America. The following two are from the Capuchin Ignace de Paris and the Recollect Chrestien LeClercq, both from mendicant orders which were part of the Franciscan family. The last three are from missionaries from the Missions Étrangères de Paris, an order also devoted to evangelisation.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify challenges missionaries faced in converting the Mi’kmaq to Catholicism

- Identify and reflect on the differences between the missionaries’ approaches to those challenges and their depictions of the Mi’kmaq.

- Use automated text analysis technology to analyse historical documents.

Technologies used for this lesson

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

- Voyant Tools is a web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts. It is a scholarly project that has been designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public. Read more about Voyant Tools.

Instructions

Documents

-

- Pierre Biard, Relation de la Nouvelle France, 1616, excerpt from chapter X, “On the Necessity of Thoroughly Catechizing These People Before Baptizing Them,” in Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Jesuit Relation and Allied Documents vol. III (Cleveland, Burrows Brother Company, 1896), p. 143-149.

- The Jesuit Pierre Biard spent two years in Port-Royal from 1611 to 1613. He is the first missionary to write a Relation describing his experience in New France at that time limited to a very small part of Mi’kma’ki territory. In these early years of the colony, the evangelisation of Indigenous people was crucial to maintain the favour of the French crown and the devout and wealthy investors. Despite the pressure imposed by colonial administrators, Biard insisted on the importance of providing religious teaching and ensuring that the Indigenous people who requested baptism were true believers. He believed that quickly incorporating Indigenous populations into the Church without genuine faith meant that the new converts would maintain their old beliefs and superstitions.

- Open Biard document [link opens in new window].

-

Julien Perrault, “Relation of certain details regarding the Island of Cape Breton and its Inhabitants,” 1635. In Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Jesuit Relation and Allied Documents vol. VIII (Cleveland, Burrows Brother Company, 1897), p. 157-167.

- The Jesuit Julien Perrault was appointed to the Cape Breton mission in 1634 to serve as a pastor for the French fishermen who lived at or frequented the post. He remained there for two years. However, in the short report he sent to his French provincial, we find a precious early ethnographical depiction of the Mi’kmaq, made in the typical writing style of the Jesuits.

- Open Perrault [link opens in new window].

-

André Richard, “Of what Occurred at Miscou,” 1644. In Reuben Gold Thwaites,The Jesuit Relation and Allied Documents XXVIII (Cleveland, Burrows Brother Company, 1898), p. 23-37.

- We do not know much about the Jesuit André Richard except that, as Julien Perrault, he was appointed to the Cape Breton mission in 1634. He was eventually transferred to the parish of Miscou in the Baie des Chaleurs. In 1644 he wrote a report on his experience there.

- Open Richard document [link opens in new window].

-

Ignace de Paris, excerpt from “Letter from the Capuchin Father R. P. Ignatius.” In PH. F. Bourgeois, Les Anciens Missionnaires de l’Acadie Devant l’histoire ( Shédiac, Presses du moniteur acadien, 1910), p. 88-97.

- Ignace de Paris was a Capuchin priest. He arrived in Port Royal in 1641. At that time, the Capuchins had missions in Port-Royal, Saint John River, Canseau, Saint-Pierre, Nipisiguit and Pentagouet. He served as superior in Pentagouet from 1646 to 1647. He wrote a report in 1656 on the situation in Acadie to the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda who until then had supported the presence of the Capuchins in Acadia. It was a difficult time for the Capuchins who had been expelled by the English after they took over Port Royal in 1654. Rome, unlike France, had little interest in such an unstable region as Acadie, and his pleas went unanswered. Capuchins did not return to Nova Scotia until the end of the 19th century.

- Open de Paris document [link opens in a new window].

-

Chrestien LeClercq, New Relation of Gaspesia, 1691, excerpts from chapter VII, “On the Ignorance of the Gaspesians,” William F. Ganong, trans. (Toronto, The Champlain Society, 1910), p. 131-135.

- Chrestien LeClercq was a Recollect missionary. He was appointed to the mission in Percé in 1675 specifically to serve the Mi’kmaq. He wrote about his 12 years’ experience among them in his ‘New Relation of Gaspesia,’ published in 1691, where he provides precious information on the customs of the Mi’kmaq. After learning their language, LeClercq developed a writing system using pictograms as a tool to facilitate the transmission of the Christian principles.

- Open LeClercq document [link opens in a new window].

-

Louis-Pierre Thury, extract from “a letter from Sieur de Thury, missionary, October 11. 1698.”

- Louis-Pierre Thury, a missionary from the Missions Étrangères, was sent by the Bishop of Québec to install a mission in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki in 1684. Thury first chose Miramichi, where he stayed for three years, then moved to Pentagouet for eight years. He became vicar general of Acadie in 1698 and founded another mission in Pigiguit. He was very involved in the politics of the region and took an active part in many Abenaki expeditions against the English.

- Open Thury document [link opens in a new window].

-

Pierre Maillard, Letter 1 Oct, 1738 and Letter 13 Oct, 1751, and Excerpt of a “letter from M. l’Abbé Maillard on the Missions of l’Acadie and

particularly on the Mi’kmaq Missions, sent to Monsieur de Lalane, grand vicar of Langres et superior of the Missions Étrangères seminary in Paris”, in Les

Soirées Canadiennes, Recueil de littérature Nationale (Québec, Brousseau frères,

1863), p.310–317.- Pierre Maillard, a missionary from the Missions Étrangères, arrived in Louisbourg in 1735. Exceptionally talented, he quickly mastered the Mi’kmaw language and perfected the hieroglyph system developed by Le Clercq, which permitted him to write down prayers and songs in Mi’kmaq and translate some of their treaties. Very devoted to his missionary task, Maillard served the Mi’kmaq throughout Acadie/Mi’kma’ki and was known as the apostle of the Mi’kmaq. He was very involved in politics and resented the presence of the Recollects, who he accused of being corrupted. Because of his close connections with the Mi’kmaq, he took part in their military campaigns during the French-English conflicts. You have two of his letters, one dated 1738 and the other dated 1751.

- Open Maillard document 1 [link opens in a new window]

- Open Maillard document 2 [link opens in a new window]

-

Jean-Louis Le Loutre, Letter 1 Oct, 1738

- Jean-Louis Le Loutre is a controversial figure perceived by some historians more as a French agent than a devoted missionary. Coming from the Missions Étrangères, he arrived in Louisbourg in 1737. While he was supposed to serve as a parish priest in Annapolis Royal, he stayed first in Maligouèche with Pierre Maillard to learn the Mi’kmaw language. He continued the next year with his missionary work in Shubenacadie, from where he served the Mi’kmaq and the French through a vast territory from Cap Sable to Chedabouctou. Like Maillard, he was deeply involved in the conflicts and encouraged the Mi’kmaq in their attacks against the English.

- Open Le Loutre document [link opens in a new window].

- Pierre Biard, Relation de la Nouvelle France, 1616, excerpt from chapter X, “On the Necessity of Thoroughly Catechizing These People Before Baptizing Them,” in Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Jesuit Relation and Allied Documents vol. III (Cleveland, Burrows Brother Company, 1896), p. 143-149.

References

-

- Archives nationales d’outre-mer COL C11D 3/fol.118-132. https://nouvelle-france.org/eng/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=7243&

- SME-Fonds Séminaire de Québec / SME2-L’administration au Séminaire de Québec / SME2.1-La correspondance précieuse / Lettres P, no 64. https://collections.mcq.org/objets/270886

- Lettres P, no 68. https://collections.mcq.org/objets/270890

- SME-Fonds Séminaire de Québec / SME2-L’administration au Séminaire de Québec / SME2.1-La correspondance précieuse / Lettres R, no 87. https://collections.mcq.org/objets/268460