Module 1: Historical Geography & Critical Cartography

Lesson 1.2: Imperial Designs

Introduction

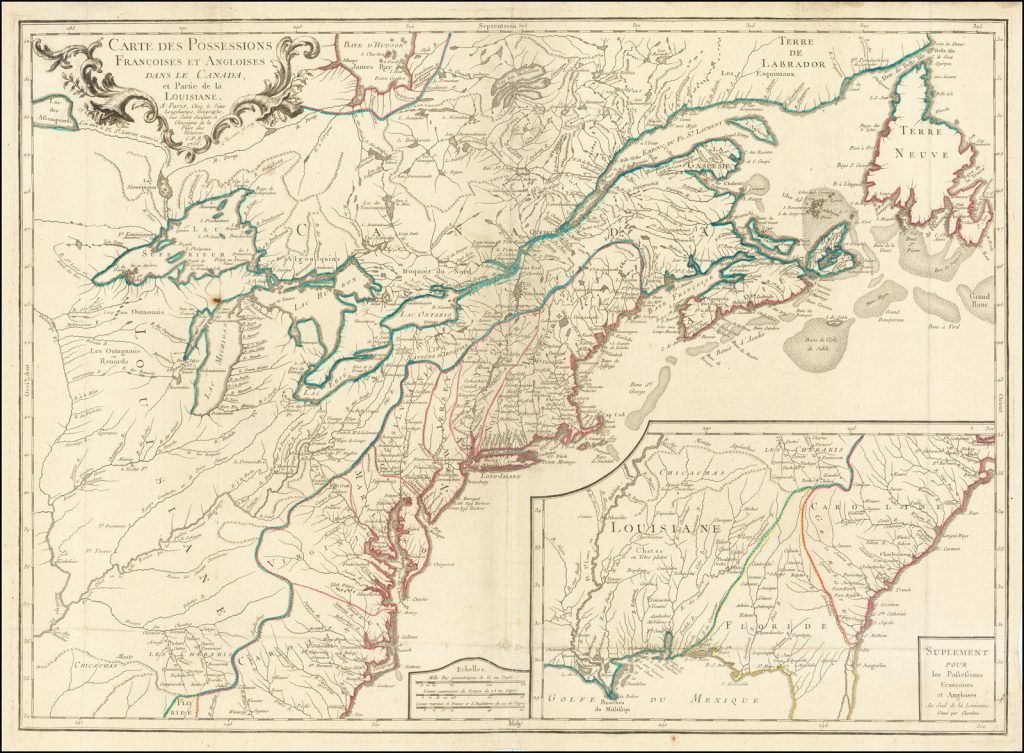

This lesson encourages you to “read” maps critically – that is, to evaluate maps as having a point of view, and as being far more subjective than we often imagine. The map at the head of this page is a good example. It wants us to take its information at face value – as objective fact. But we can see from the image that the mapmaker made choices. Across that broad region now commonly identified as the Canadian Maritime provinces is written “New Scotland.” But compare that with the next map (immediately below), a detail from Vicenzo Coronelli’s America Settentrionale from 1688, which shows that space as partly “Acadia,” and partly “Les Etchemins.” So why are two maps of the same region, made at about the same time, so different? And who are the Etchemins? Which map is right? Is either of them right? And how can we tell?

Maps can tell stories and have points of view. They don’t always show you “what is,” but what the mapmaker wants you to see. This issue was very much on the mind of colonial officials in Britain and France in the 1750s as they struggled to clearly define the boundaries of Acadie. Maps, as we’ll see in this lesson, were a key feature of both French and British land claims. Maps seem to be “objective,” and their grounding in Enlightenment science and its methods of explaining the world gave them an appearance of certainty. So, why were the maps so different from each other?

In 1710, British forces captured Port Royal, the capital of the French colony of Acadie. Three years later, in the subsequent peace treaty (the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713), Acadia “with its ancient boundaries” was passed permanently into British control. That seems straightforward enough, except that no one had described Acadia’s “ancient boundaries.” Where was Acadie?

There was little doubt then, as now, that “the ancient limits of Acadie” centred on what we today call Nova Scotia. But the boundary lines were much less clear.

During the war the British had captured the colonial capital, Port Royal, but once the treaty confirmed their possession of the region they did little more than administer the town. Indeed, the people of Acadie were mostly farmers living between 20 and 100 km away from Port Royal. They had limited interaction with British officials, and the British made little effort to govern these French Catholics. Most Acadians went on with their lives, and many actually prospered under the new conditions of peace with “les Anglais.” By the 1740s, Acadians outnumbered English-speaking Protestants in the area by more than 10 to 1. The British believed they were the sovereign power in all of what they called Nova Scotia, but in terms of actually governing people, their reach was small.

Militarily, the British were perhaps even weaker. The Mi’kmaq, along with their Wabanaki allies in what is today New Brunswick and northern New England, were without doubt the preeminent military power in the area. And yet, as we’ll see, their views – and in some ways even in their existence – had limited impact on the process of drafting the maps, or the political understandings that would emerge in the period. In this instance, what we don’t see may be at least as important as what the mapmakers chose to show.

This module asks you to explore the same questions that occupied those colonial administrators and diplomats: what was this place called Acadie? Where exactly was it located? Where were its boundaries?

Unlike the administrators, you don’t need to draw lines on a map; in fact there’s little point in determining who was ‘right.’ You just need to ask yourself, in the mid-18th-century, who and what defined this place? Or was it ‘these places’? What does seem clear is that neither the British or the French held clear control of this territory. There were local areas where the nature of the control seemed evident, but even then, power was far from unimpeded.

In this lesson we’ll follow the ideas of historian Elizabeth Manke, in that it might be helpful to think less about sovereign colonial states, and more in terms of what she calls “spaces of power”: locations in this larger territory that the British dominated, others that the French (or perhaps the Acadians?) dominated, and those that the Mi’kmaq dominated. Those spaces of power weren’t often clearly delineated on maps, but for us as historians, looking back on that time, it may make more sense to think in those terms rather than about official states and boundary lines.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Evaluate a map beyond its content, and identify a strategy or argument.

- Explain the British and French cartographic strategies for controlling Acadie/Nova Scotia.

- Explain maps as tools of cartographic imperialism.

Technologies Used

- hypothes.is is a web-based social annotation tool that runs as a plug-in on this site. When you access the pdf documents below you will have access to the functionality. Note that you will need to have an account to use this tool. Through the following links, you can read hypothes.is’ privacy policy, terms of service, community guidelines, and access hypothes.is help.

Instructions

Documents

1. The British interpretation of Utrecht:

2. The French interpretation of Utrecht:

3. “All the memorials of the courts of Great Britain and France: since the peace of Aix la Chapelle, relative to the limits of the territories of both crowns in North America; and the right to the neutral islands in the West Indies” (The Hague, 1756).

- The negotiations between Britain and France over these territories (as well as over the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia) lasted over twenty years and were very complex. This document summarises the British and French positions.

- Open Memorials of the Courts [link opens in new window]

4. “Letter from William Shirley, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay, to the Board of Trade, 16 October 1744″, in Correspondence of William Shirley : governor of Massachusetts and military commander in America, 1731-1760 (New York, MacMillan, 1912), pp.150-51.

- Peace rarely prevailed in Mi’kma’ki, though the period from 1726 to 1744 was fairly stable. But it was not only the British military who sometimes acted against the Mi’kmaq. The ongoing presence of New England fishing fleets and occasionally that of privateers meant that there were lots of opportunities for British actors (if not always British state actors) to anger Mi’kmaw peoples. Here you’ll read the perspective of the British governor of Massachusetts. Why Massachusetts and not Nova Scotia? While Britain assumed control of the colony after 1713, Britain expended few resources in developing the area; its government was heavily dominated by the larger, older colony of Massachusetts. Moreover, most commercial interests in Nova Scotia – fishing fleets, merchants, and land developers – were from Massachusetts. Nova Scotia was, at this point, as much a colony of Massachusetts as of Britain.

- Shirley’s declaration of war [link opens in new window]

5. Jacques l’Hermitte, Carte de l’Isle Royale, rectifiée sur les anciennes, sur l’original des sauvages, & les Observations faites en 1716 & 1717 [reprinted, Jacques Bellin, Paris, 1744]