5 Chapter Five: Evaluating Your Impact and Evolving your practice

Yelin Su and Lisa Endersby

Reflect back to reason forward

Y. (2018, April 04). 16074 Teaching Commons eCampus Project Video 3 Reframing. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYljX28gF4c

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one’s actions so as to engage in a process of continuous learning (Schön, 1983). For practitioners, it involves “paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice reflectively and reflexively. This leads to developmental insight” (Bolton, 2010). A key rationale for reflective practice is that experience alone does not necessarily lead to learning; deliberate reflection on experience is essential (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999; Loughran, 2002).

Reflective practice can be an important tool in practice-based professional learning settings where people learn from their own professional experiences, rather than solely from formal training and knowledge transfer. It may be the most important source of personal professional development and improvement. It is also an important way to bring together theory and practice; through the process of reflection a person is able to see and label forms of thought and theory within the context of his or her own work (McBrien, 2007). A person who reflects throughout his or her practice is not just looking back on past actions and events, but is taking a conscious look at emotions, experiences, actions, and responses, and using that information to add to his or her existing knowledge base and reach a higher level of understanding (Paterson & Chapman, 2013). Reflecting back is an extremely effective method of reasoning forward.

Reflective practice. (2018, April 11). Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reflective_practice

One way that your reflective practice and associated insights may be formalized is through the process of evaluation. Evaluation is an integral part of any instructional design and development regardless of the delivery mode of the instruction. In an ideal situation, any instructional design and development is a recursive process where evaluation is central stage and a recurring theme embedded throughout the whole process. A reminder about the terminologies we discussed in the previous chapter — in our book, the ‘Evaluation’ refers to measuring the effectiveness and quality of a course or instructional unit while the “Assessment’ is concerned with student learning.

As a central stage in the instructional design and development process, evaluation does not happen only at the end of each individual cycle or stage. On the contrary, evaluation should be threaded throughout the whole process to systematically collect multi-dimensional evidence on not only the effectiveness and the quality of the instruction but also the design and development process. As such, evaluation is the on-going reflection on the instructional design and is inherently continuous and mainly formative in nature. In this chapter, we will discuss planning an evaluation plan to document impact of the instruction and how they could be adopted to document the impacts of the instruction for SOTL.

Formative and summative evaluation

With evaluation as an integral and recurring theme, the instructional design and development becomes an ongoing process of planning, implementation, and review. To document the impact and effectiveness of an individual course, both formative and summative evaluation can be planned and conducted at different stages of the course design, development, and delivery.

Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation asks the question “how are we doing so far” before the instruction is fully developed or finalized. It measures whether and how well the instruction has met its goals while it is still “forming” (Morrison et. al, 2013). In the field of instructional design, it is thought to be most valuable to have formative evaluation embedded early in the initial design and development process and pilot newly developed course units/courses before its first delivery (Morrison et. al, 2013). Evaluating at early stages of the process allows time for timely revision and helps avoid wasting time and resources on instructional aspects that don’t work well.

In higher education, it is not always feasible to pilot newly designed and developed instruction before the first delivery. On the other hand, instructors in higher education may refine their instruction for each iteration of the course according to their prior teaching experience and students’ feedback. It is common practice in higher education to conduct formative evaluations during the first delivery of the newly designed and developed instruction and in each iteration of the instruction, particularly after major revisions. It is not uncommon that in higher education, formative evaluation is often an integral part of the lifecycle of a course and the instruction is always evolving.

The instruction is always evolving and Formative evaluation is the process of collecting and analyzing multidimensional data from various sources to examine the effectiveness of the developing instruction. As the formative evaluation is developmental in nature, it focuses on both the process of the instruction (such as instructional strategies, teaching methods, students attitudes, etc.) and the product of the instruction (student performance) to judge whether certain course features are working or not. Some of the commonly asked questions in formative evaluation include

- Are there any weaknesses and strengths in students’ achievement in learning outcomes?

- Was the student workload reasonable?

- Were the learning activities appropriate to the knowledge and skills that students were asked to learn?

- Were the learning activities manageable to students?

- Were the materials easy to access?

- Was the instruction organized and sequenced appropriately?

- Did the assessment satisfactorily measure student’s achievement in the learning outcomes?

- Were there sufficient technical support for students?

- What were students’ reactions to the learning management system?

To answer these questions, data from various resources are usually collected and analyzed to determine the effectiveness of course features and to provide suggestions for further improvements. You might consider to:

- Ask experts (subject matter and instructional design) to review course materials and design for feedback early in the design and development phase

- Pilot prototype instructional units with students before finalizing the design

- Observe student’s interaction with the course materials during the delivery

- Gather early feedback from your students during course delivery to see what’s working and what is not working

- Analyze students performance data to gauge whether the instruction has been successful during the course delivery

Summative Evaluation

Summative evaluation is typically used to assess the instruction’s effectiveness in reaching their goals after the instruction is implemented. Contrary to the formative evaluation, which is developmental in nature, the summative evaluation seeks to make unbiased and evidence-based decisions on whether the instruction has met its expected outcomes after the delivery. As such, the summative evaluation focuses more on the product of the instruction (e.g. whether students met or achieved the intended learning outcomes) than in the instructional processes. Depending on how the instructional effectiveness and goals are defined and operationalized, summative evaluations might ask similar questions as formative evaluations. Summative evaluation may ask questions such as:

- Are there any weaknesses and strengths in students’ achievement in learning outcomes?

- Was the student workload reasonable?

- Were the learning activities manageable to students?

- Were the materials essential and effective for students learning?

- Were there sufficient technical support for students?

- What were students’ opinions on quality of the instruction?

- If improvements are needed, how can they be made most effectively?

Summative evaluation is not a one-off exercise. It is valuable to systematically collect summative data shortly, if not immediately, after each implementation of the instruction. The analysis of the accumulated summative evaluation data tracks the strength and weaknesses of the instruction continuously to reveal areas for further improvements. Sometimes, after the instruction has been delivered for a period of time, stakeholders might also be interested in investigating the long term impacts of the instruction. In this case, confirmative evaluations will be conducted. The confirmative evaluation is the summative evaluation that measures the longer term effects of the instruction, particularly learners’ performance in learning outcomes in actual performance environment (e.g. at the workplace). It usually happens after a longer period of time of the course completion. Learners who have completed the instruction might be contacted for a follow-up evaluation to gauge whether and what the long-term benefits are of taking the instruction in their actual performances.

Student’s performance data, such as posttest scores and exam marks, are often collected as key information resources to judge the effectiveness of student learning. However, similar to the formative evaluation, summative evaluation also require collecting other data from multiple sources , such as efficiency of the instruction (time required for learning), cost of the instructional development and delivery, and student satisfaction, to determine the effectiveness and the cause.

Overlapping Formative and Summative Evaluation

Formative and summative evaluation differs in its purposes, emphasis, and is conducted at different times of the instructional design and development process. They share many similarities and their purposes often overlap. It is easier to clearly differentiate the formative and summative evaluation if we consider them in the context of a single cycle of instructional design and development process. However, in reality, the instructional design and development is a recursive process in which evaluation is a recurring theme embedded into all stages of the process. The evaluation becomes also a continuous and iterative process by itself and the distinction between the formative and summative evaluation becomes blurred. Many times, evaluations can be both formative and summative in nature as their results can always be used to both determine the effectiveness of the instruction and to inform the further improvement.

Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model

In general, evaluating instructions is to examine the effectiveness and quality of the instruction to determine whether it is successful in meeting its purposes, why it is successful, and how to improve. However, the “effectiveness” and “quality” of the instruction could be defined very differently depending on the stage(s) of the instructional design and development in which the evaluation will be conducted. Who is doing and/or funding the evaluation might also have an impact on how the the “effectiveness” and “quality” of the instruction is defined and meansured. While one course instructor wants to know whether a course is successfully teaching what it is supposed to, the other instructor is wondering about whether a pretest should be added in a particular course unit to provide information for the timely adjustment of the instruction, and an administrator is interested in finding out whether the curriculum should be continued as is, revised, or terminated. The different definitions of “effectiveness” and “quality” in various circumstances will, in turn, inevitably lead to different approaches to evaluation.

Every evaluation is biased in it only measures aspects that stakeholders deem relevant and crucial. Despite the criticisms, Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model remains the most popular model to provide guidance on what to measure to gain a more comprehensive understanding on the “effectiveness” of the instruction.

In the kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model, Kirkpatrick (1996) proposed a four-step evaluation model to measure the effectiveness of training programs: participant reaction, learning, behavior, and results.

Participant reaction is the first step of the evaluation. Measuring participant reaction is to gauge learners’ self-perceptions on whether they have enjoyed the instruction and how much they’ve learned. Measuring participant’s reaction with course evaluation is one of the most popular evaluation practices in higher education. However, participants reaction does not necessarily correlate with what participants have actually learned.

The second level of evaluation is to measure learning. This refers to using students assessment data to directly determine whether and how much learning has happened upon the completion of the instruction. This usually involves using pre and post tests, having learners take standardized exit tests, or using samples of relevant students classwork to demonstrate student’s learning.

The third level of evaluation is behavior or performance measurement. This level measures learners’ on-the-job performances, i.e., whether learners can transfer the knowledge, skills, and aptitudes that they’ve learned to the job. In higher education settings, behavior or performance evaluation is often measured by student’s performance in internship programs, in capstone project, and in a learning portfolio.

The fourth level of evaluation is results, which measures whether the instruction has helped bring the macro-level results the stakeholder is ultimately aiming at. For example, in the context of a for-profit organization, the results might be the increased sales, customer satisfaction, and decreased accidents. In the context of higher education, the results might be increased student employability, graduate school admission, research productivity and so on. Though highly desirable, it is very difficult to operationalize and measure these macro and long term results. In higher education, the fourth level of evaluation are sometimes conducted via alumni surveys and employer questionnaires.

Though ideally, course instructors and other stakeholders might want to collect multi-facet data on several or even all four levels of evaluation, in reality, it is not always feasible or necessary for each individual course/program.

After completing any level or degree of an evaluation process, you may be left with a large amount of information or data that could meaningfully inform your practice. Most evaluation models often end with the collection or dissemination of data, without considering how this information might support program improvement or individual professional development. The next section of this chapter will provide you with some suggestions for how you might leverage the opportunity from having access to insights into your teaching to not only learn from your experience but how to implement these insights into your future teaching practice.

Once you have had the opportunity to use data and other information gained from an evaluative process, it is good practice to share your findings with colleagues. Given the highly interconnected nature of education as a discipline, many of us are often working on very similar projects or working through similar professional challenges, which may benefit from lessons learned in the field. The final section of this chapter discusses the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) as a means to more formally gather and disseminate your reflective insights to contribute to ongoing conversations meant to advance our collective practice.

Documenting and Disseminating – The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

Through a SoTL lens

The formalized process of validating what it is about your course that is working, and what part of your designs align with what is working (and not) is the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL, pronounced“sō-tul”). It provides a scholarly lense (inquiry and rigor done deliberately and systematically) to your hard work, and curiosity.

So what is your hypothesis? Often this can be determined by reflecting on your reasons for incorporating a particular activity or assessment in your course blueprint. For example, if you believe strongly that your learners need to research a controversial issue and then participate in a debate, taking opposing sides so that you can effectively assess their ability to reason, an inquiry into the beliefs that led to the design and facilitation of this activity can provide you with extremely valuable re-design evidence, and could benefit your colleagues if you choose to share you results. A common first SoTL kind of question for this activity is an “Is it working?” question, and a second question is a descriptive questions about “What went on?”. A related third questions could perhaps include “What would it look like if…?”.

So what is your hypothesis? Often this can be determined by reflecting on your reasons for incorporating a particular activity or assessment in your course blueprint. For example, if you believe strongly that your learners need to research a controversial issue and then participate in a debate, taking opposing sides so that you can effectively assess their ability to reason, an inquiry into the beliefs that led to the design and facilitation of this activity can provide you with extremely valuable re-design evidence, and could benefit your colleagues if you choose to share you results. A common first SoTL kind of question for this activity is an “Is it working?” question, and a second question is a descriptive questions about “What went on?”. A related third questions could perhaps include “What would it look like if…?”.

By asking “How do I know if my students are learning?” and “Will my student’s learning last?” you can uncover what most interests or eluded you about your students’ success that can’t be answered simply by interpreting the results submitted by regularly assigned course work (Bernstein & Bass, 2005, p. 39).

C. (2013, September 11). Taxonomy of Questions from the Intro to Opening Lines. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCxPttq_e_Y

What does SoTL look like in practice?

It can be difficult to consider where this type of deeply reflective practice might fit in an already busy schedule of teaching, programming, and meetings. In practice, however, SoTL is much more than a strictly academic exercise. As discussed in previous sections of this chapter, the scholarship of teaching and learning is a way to formalize and disseminate what we already do in our daily practice – reflection for and in practice.

Compiling teaching portfolio

Teaching portfolios, also called teaching dossiers or teaching profiles, are pieces of evidence collected over time after they have been developed, tested, revised. They are used to highlight teaching strengths and accomplishments (Barrett, n.d.; Edgerton, Hutching & Quinlan, 2002; Seldin, 1997; Shulman, 1998). This collection of evidence can be paper based or electronic. Teaching portfolios can usually be integrated into self-assessment sections of performance appraisal requirements. No two teaching portfolios are alike and the content pieces can be arranged in creative and unique ways.

Reflective inquiry is a critical element in any portfolio and reflections about teaching approaches that failed, as well as those that succeeded, should be included (Lyons, 2006). Both goals that have been accomplished and specific plans for accomplishing future goals should be noted. Another segment of the portfolio could list certifications earned; workshops, conferences or other educational events attended; papers written about clinical teaching in a course; and awards received.

Teaching products could constitute another segment, such as writing a case study about a typical client in your practice setting; developing a student orientation module for your students; crafting a student learning activity such as a game or puzzle; devising an innovative strategy to support a struggling student; or demonstrating a skill on video. Mementos such as thank-you messages from students, colleagues, agency staff or clients could also be included. Distinguish between pieces of content that can be made public and those that should be kept as private records. For example, a student learning activity might be made public by publishing it in a journal article or teaching website, while mementos would be private and would likely only be shared with supervisors.

In all the ways that you gathered formative evaluation data, while delivering your course activity and assessment, you have created an opportunity to frame your portfolio with your narrative about teaching and learning, and how you positively affect the learning process. Don’t forget to gather formative evaluation of your course facilitation at a few point in your course. Provide a mechanism that is fully anonymous, for example an online survey, where students can comment on what is going well, what is not going well, and what advice they would like to give you.Your portfolio can share your responses to the feedback, your evaluation of the process, and future re-design plans triggered by this feedback. The possibilities for demonstrating instructional achievement is limitless.

Accessing communities of support

The instructor role is crucial for the successful implementation of blended and online learning (Garrison & Vaughan, 2008). Although teaching staff are experts in their respective fields, they may not have the expertise and experience to design and implement blended/online learning in their courses. Scholarship and professional development, much like many practices in teaching and learning, is not a solitary pursuit. At many institutions, centres for teaching and learning, as well as offices for institutional research, offer resources for helping us define and carry out our research. More importantly, these offices contain people who bring diverse perspectives and complementary competencies to an exploration of student learning and the ongoing development of our professional competencies.

Colleagues who teach may be well versed in the research surrounding their area of speciality, but they may remain curious about a more systematic review of teaching (whether in their own experience or the broader practice of instruction). How might you engage with colleagues to explore the art of teaching at your institution? How can you leverage the research and analysis expertise of your peers to promote, celebrate, and share good practice? SoTL is an interdisciplinary, collaborative practice. Working with and within a community of practice offers access to knowledge held with individuals, often a more dynamic, contextually-relevant record of practice than can be contained in books and journals. This knowledge is especially useful to practitioners as they demonstrate the ‘how’ of more generalized knowledge, responding to local circumstances that demand particular behaviours and strategies (Wenger, 2008).

While some aspects of academia may emphasize a solitary pursuit of publication and status, these communities of practice (whether formalized or informal groups) can more effectively and efficiently leverage knowledge in pursuit of our professional development. If our ultimate goal is to better support student success, these communities offer a valuable space to share the work and join in our celebrations of advancements in the field.

Contributing design-based research

Many professionals in higher education, whether they teach in a formal classroom or not, are expected to give back. Often, this may look like calls to serve on committees or participate in charitable initiatives. It can also take the form of the service we provide when we recognize and share our insights, questions, and lessons learned for the collective pursuit of student success. While perhaps not always recognized within more formal structures, these endeavours are incredibly important to our profession. Just as our students, our institutions, and the world at large continue to evolve, so too must our thinking about how, when, and what we teach. Design-based research offers some important first steps into contributing to the field in a practical, meaningful way.

As we conduct research about our practice, we will begin to gather and interpret insights from the very spaces and situations that will most benefit from these new ideas. We may often see or have for ourselves an insight into practice that seems particularly intriguing; one that could help fix a problem or approach a particular teaching strategy in a new way. However, these innovations are only as meaningful as their utility in practice. Design-based research emphasizes the importance of context – research takes place in naturalistic settings and continuous adjustments to experimental conditions (such as making small, incremental changes in how content is delivered) mimics our more traditional understanding of scientific inquiry (Barab & Squire, 2004). In this way, we are able to both investigate phenomena that may support our teaching while also learning how these approaches work (or don’t work) in our unique learning environments.

Disseminating our Knowledge

Our reflections often lead to important insights that can inform our practice. However, these insights are not meant to remain behind a locked filing cabinet or office door. The work of presenting at conferences and writing journal articles are two of many strategies that help to strengthen our SoTL community. With continued advancements in communication technologies, the Internet has also opened many previous barriers to sharing our knowledge across geographic, institutional, and discipline-defined boundaries.

When considering where you might be able to share your insights and ideas, it is helpful to determine where your work may be most useful. This will depend on, in part, what type of research you have done and the intended audience for your findings.

Sharing Your Ideas Locally

Your initial research may be most useful right within your own department or institution. What opportunities might be available to share your insights with colleagues who may be facing similar challenges and who may be able to act on your findings more or most immediately? Consider sharing your research through:

- Departmental or Institutional Newsletters

- Departmental Committee Meetings

- Teaching and Learning Committees

- Informal Research Talks or Gatherings

Sharing Within Your Discipline

Beyond your local institution, many colleagues in your shared discipline may also be working through similar challenges that you have been investigating. You may also find that your work lends itself to more generalized insights or broader questions that could inform your discipline or field as a whole. In these cases, it may be most helpful to locate avenues for dissemination that engage a wider audience:

- Discipline-Specific Newsletters or Blogs

- Local/International Conferences

- Professional Associations, including ISSOTL and STLHE

Publishing Online

The SoTL community is truly international, spanning many countries where teaching and learning remains at the forefront of our priorities at postsecondary institutions. Offering an international scope to your research invites many diverse perspectives while also broadening your own networks and community of practice. Taking advantage of online tools and technologies can help invite broader conversations that support our own learning and development. Disseminating your work to this wider audience could include venues such as:

- Blogging (Creating your own or contributing)

- Social Media (Twitter Hashtags or Facebook Discussions)

- On Twitter: #edchat, #highered, #edu

- Publication Sharing Sites (e.g. Academia.edu)

- Professional Discussion Forums (often run by professional associations)

- Submitting to online research journals

- Applying for research grants (funding typically includes a responsibility to publish findings)

Disseminating our work often leaves us open to scrutiny and feedback. While perhaps not always comfortable or desired, these conversations are critical to the continued advancement of our practice, field, and scholarship. Here again we can see the work of SoTL as encouraging and engaging in a dialogue. Our work may be undertaken for the immediate benefit of our own students or institution, but the field of teaching and learning shares many universal values related to student success and instructor effectiveness. When we pause to consider our common goals and shared passions, disseminating our knowledge becomes far more than a means to gain notoriety or elevate an agenda. Dissemination confirms and extends our shared values, while creating space to question and extend our values as our contexts, students, and institutions continue to evolve.

Reflection offers practitioners an opportunity to “better understand what they know and do as they develop their knowledge of practice through reconsidering what they learn in practice” (Loughran, 2002, p. 34). Schön’s (1983) seminal work highlighted the important link between reflection and practice, explicitly naming the reflective practitioner as a goal for educators in the field.

One goal of reflective practice is to actually make use of the insights gained through your learning. Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning (1984) includes a key step in active experimentation, meant to encourage using our assessment data as a way to pilot meaningful change. Rather than making a best guess, this stage emphasizes the use of evidence in our re-design of teaching strategies and classroom activities, from the smaller scale work of implementing an active learning strategy in primarily lecture based course through to larger changes of setting new precedents or principles driving how we respond to new challenges in the field.

Re-Design for the Classroom

The classroom is an important living laboratory for our scholarly exploration of teaching and learning. Unlike some other laboratories, however, we are investigating a who, not a what. Our opportunities for re-design based on the evidence we gather in pursuit of SoTL are meant to benefit and support our students in their ongoing learning and development. This evidence supports a model of continuous improvement in a context that allows us to control, to some degree, not just if we change, but how that change may occur.

When considering using assessment data as evidence for change, remember that change is done by, for, or with others. How will your students be involved in this change? Your students have agency to participate in your classroom re-design – what motivates your students to try something new? Are these the same things that might motivate you? Change at the local level respects context and formative gain; SoTL in and for the classroom can therefore offer insights and opportunities to course correct along the learning journey or provide insight into a timely challenge.

An evidence-based redesign of a classroom activity or learning strategy is a complex undertaking. When considering any change to your practice, it is important to consider questions like:

- What data are you using to drive this change? Where did it come from? Is this data you collected yourself or was it provided to you by another source? Consider the validity, accuracy, and motivation behind any data that drives change. Information is often only as valuable as its interpretation.

- Who will help you champion this change? Who will be your partner in motivating, persuading, and leading during this process?

- Who will be impacted by this change? Will some students benefit more than others?

- How will you assess the impact and effectiveness of your change? Will you only assess at the end of a predetermined amount of time, or will you look for formative opportunities to potentially course correct along the way?

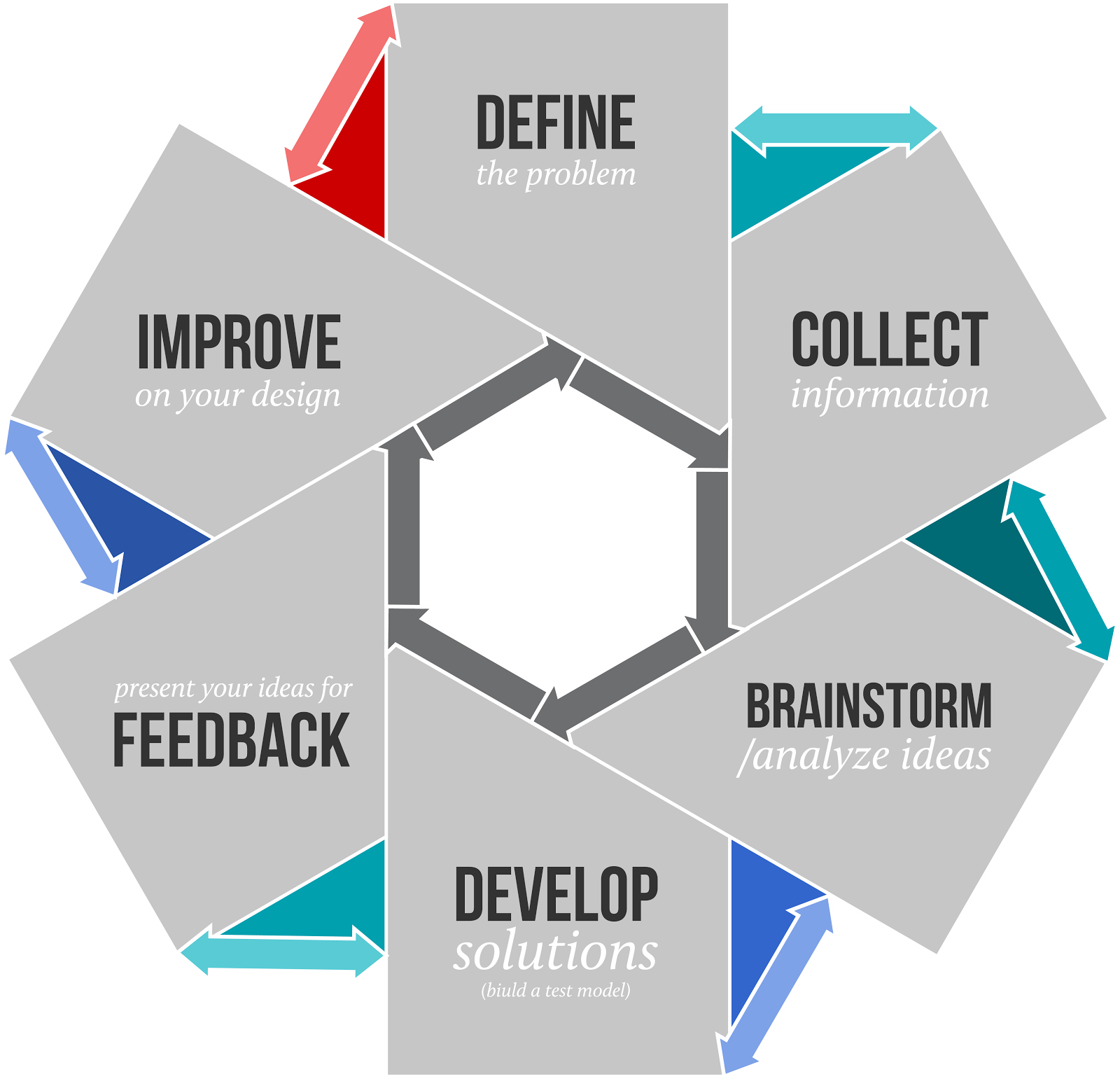

Evidence-based redesign follows a model akin to research and scholarship. The figure below outlines a simplified process for using a design-thinking approach to the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Re-Design for the Scholarly Community

Our work in the classroom often has a broader impact than within the walls of our institutions. The education community is rich with ideas, lessons learned, and promising practices that have been informed by work on a smaller scale that, through multiple iterations, has been tried, tested, and examined for continuous improvement. This community of practice holds decades of knowledge that can be leveraged to support our own unique teaching contexts. With such a rich field to draw on, it is imperative that we consider how we might contribute to, rather than only draw from, this unique community.

In addition to our previous discussion of disseminating our research findings, re-design for the scholarly community also involves the concurrent and sometimes more intangible work of creating and fostering this community. The field of education, much like the humanities, can at times appear to be populated by the archetype of lone, solitary authors engaged in primarily independent scholarship (Cronin, 2003). This often runs counter to our collegial, collaborative work within our home departments and institutions. Your work in disseminating research findings, including the results of your own investigations in and outside the classroom, serve not only to build a body of knowledge but also to enhance and strengthen our larger community of practice. Engaging with and contributing to these communities of practice allows us to retain knowledge in ‘living ways’ through considerations of both tacit and explicit knowledge relevant to practice, distribute and reinforce the responsibility of lifelong learning, and shape our identities as professionals continuing to develop our knowledge and competency in the field (Wenger, 2008).

Chapter Summary

The title of this chapter is intentional. Practitioners must continue to hold themselves to the same standards and expectations we hold for our students in lifelong learning and continued, reflective practice. As our students and the world around us evolves, so too must our considered approaches to teaching and learning. While the advent of online tools and digital technologies has precipitated what seems to be a nearly instantaneous shift in the what, where, and how we teach, our why remains, fundamentally, the same. Technology is a tool, not a learning outcome. As we create new pathways for learning inside and out of the classroom, our goals should be to mirror and model a practice that builds on itself by learning from itself. Technology may then help us to better collect, organize, create, and share new insights, but it is the measured, intentional act of reflection that will be the catalyst to innovations and change for effective, meaningful student learning.

Key Takeaways

Additional Resources

Researching Teaching and Student Outcomes in Postsecondary Education: A Guide

- The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO) has created a resource for investigating student learning as scholarship. The guide includes suggestions for initiating projects, collecting and interpreting data, as well as applying and disseminating results.

- This resource offers suggestions for implementing reflection in both individual and group practice. There is also a worksheet and additional information regarding a Critical Incident Reflection Framework that offers guiding questions for considering potential problems or ‘incidents’ and how reflective practice might help to mitigate these issues.

- The Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (STLHE) compiled information about SoTL from a historical and national context, including a list of relevant research in the area.

Reflective Questions

After reading this article, taking into consideration the content and examples provided in this textbooks previous chapters, what are three small methods that you could employ in your course that will provide you with evidence that could effectively, and efficiently direct your course blueprint redesign? What would you need to do to integrate these methods, and what would you do to benefit from the data you’ve gathered?

Once you’ve responded to the question, map the data you’ll gather, and how it will be directed, using the template provided.

What’s in YOUR Teaching Portfolio?

If you have not done so already, initiate a teaching portfolio and keep adding to it throughout your teaching career. Visualize a large black artists’ case that holds all the items that an artist would use to illustrate or sell work. For example, a portrait painter’s case might contain a black and white sketch of a young girl, a full-colour family portrait, and a detailed replica of a classic piece. Each item would be individual, would have personal relevance to the artist, and would reflect the artist’s skills. Similarly, your teaching portfolio will contain items that illustrate your individual interests and expertise. What’s in YOUR teaching portfolio?

A final comment

The evidence-based redesign report shared in the linked article is primarily a face to face experience, although learners are required to do pre-quiz and group work outside of the traditional classroom space. Although it’s technology enhanced, there’s certainly room to further maximize the technological potential of our connected society, as long as we remember that technology for technology’s sake is not an effective approach for you or your learners course experiences. By gathering feedback, you will be provided with themes for further refinement and some of those themes will be most effectively resolved with the integration of mobile and online technologies; one more learning space utilized to positively impact the achievement of course learning outcomes.

References

Archer, J. (2010). State of the science in health profession education: Effective feedback. Medical Education, 44(1), 101–108.

Assessment. (n.d.). In The glossary of education reform. Retrieved from http://edglossary.org/

Atherton, J. (2013). Learning and teaching: Learning contracts [Fact sheet]. Retrieved from http://www.learningandteaching.info/teaching/learning_contracts.htm

Austin, Z. & Gregory, P. (2007). Evaluating the accuracy of pharmacy students’ self-assessment skills. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 71(5), 1–8.

Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14.

Barrett, H. (n.d.). Dr. Helen Barrett’s electronic portfolios [website]. Retrieved from http://electronicportfolios.com/

Baxter, P., & Norman, G. (2011). Self-Assessment or self-deception? A negative association between self-assessment and performance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(11), 2406–2413.

Beckett, S. (1983). Worstward ho. Location Unknown: Margarana Books.

Benton, S. & Cashin, W. (2012). Student ratings of teaching: A summary of research and literature. Idea paper #50. Manhattan KS: The Idea Centre. Retrieved from http://www.ntid.rit.edu/sites/default/files/academic_affairs/Sumry%20of%20Res%20%2350%20Benton%202012.pdf

Billings, D. & Halstead, J. (2012). Teaching in nursing: A guide for faculty (4th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier.

Black, S., Curzio, J. & Terry, L. (2014). Failing a student nurse: A new horizon of moral courage. Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 224–238

Boud, D. (1995). Enhancing learning through self-assessment. London: Kogan Page.

Bradshaw, M. & Lowenstein, A. (2014). Innovative teaching strategies in nursing and related health professions education (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Brookhart, S. (2008). How to give effective feedback to your students. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bush, H., Schreiber, R. & Oliver, S. (2013). Failing to fail: Clinicians’ experience of assessing underperforming dental students. European Journal of Dental Education, 17(4), 198–207.

Carnegie Mellon. (n.d.) What is the difference between formative and summative assessment? [Fact sheet]. Retrieved from the Eberly Centre for Teaching Excellence, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA. http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/basics/formative-summative.html

Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Peer observation guidelines and recommendations [Fact sheet]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. Available at http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/resources/peer/guidelines/index.html

Centre for the Study of Higher Education. (2002). A comparison of norm-referencing and criterion-referencing methods for determining student grades in higher education. Australian Universities Teaching Committee. Retrieved from http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/assessinglearning/06/normvcrit6.html

Chan, S. & Wai-tong, C. (2000). Implementing contract learning in a clinical context: Report on a study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(2), 298–305.

Cheung, R. & Au, T. (2011). Nursing students’ anxiety and clinical performance. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(5), 286–289.

Chickering, A. & Gamson, Z. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. American Association for Higher Education AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3–7.

Colthart, I., Bagnall, G., Evans, A., Allbutt, H., Haig, A., Illing, J. & McKinstry, B. (2008). The effectiveness of self-assessment on the identification of learning needs, learner activity, and impact on clinical practice: BEME Guide No. 10. Medical Teacher, 30,124–145.

Concordia University. (n.d.) How to provide feedback to health professions students [Wiki]. Retrieved from http://www.wikihow.com/Provide-Feedback-to-Health-Professions-Students

Cronin, B. (2003). Scholarly communication and epistemic cultures. Paper presented at, Scholarly tribes and tribulations: How tradition and technology are driving disciplinary change. Association of Research Libraries, October 17, 2003, Washington, D.C. Retrieved February 22, 2008, from http://www.arl.org/bm~doc/cronin.pdf

Davis, D., Mazmanian, P., Fordis, M., Van Harrison, R., Thorpe, K. & Perrier, L. (2006). Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 296(9), 1094–1102.

Dearnley, C. & Meddings, F. (2007) Student self-assessment and its impact on learning: A pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 27(4), 333–340.

Duffy, K. (2003). Failing students: A qualitative study of factors that influence the decisions regarding assessment of students’ competence in practice. Glasgow, UK: Glasgow Caledonian Nursing and Midwifery Research Centre. Retrieved from http://www.nm.stir.ac.uk/documents/failing-students-kathleen-duffy.pdf

Duffy, K. (2004). Mentors need more support to fail incompetent students. British Journal of Nursing, 13(10), 582.

Dunning, D., Heath, C. & Suls, J. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health education and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(3) 69–106. Retrieved from https://faculty-gsb.stanford.edu/heath/documents/PSPI%20-%20Biased%20Self%20Views.pdf

Edgerton, R., Hutching, P. & Quinlan, K. (2002). The teaching portfolio: Capturing the scholarship of teaching. Washington DC: American Association of Higher Education.

Emerson, R. (2007). Nursing education in the clinical setting. St Louis: Mosby.

Frank, T. & Scharff, L. (2013). Learning contracts in undergraduate courses: Impacts on student behaviors and academic performance. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(4), 36–53.

Gaberson, K., Oermann, M. & Schellenbarger, T. (2015). Clinical teaching strategies in nursing (4th ed.). New York: Springer.

Gainsbury, S. (2010). Mentors passing students despite doubts over ability. Nursing Times, 106(16), 1.

Galbraith R., Hawkins R. & Holmboe E. (2008). Making self-assessment more effective. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 28(1), 20–24.

Gardner, M. & Suplee, P (2010). Handbook of clinical teaching in nursing and health sciences. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Gregory, D., Guse, L., Dick, D., Davis, P. & Russell, C. (2009). What clinical learning contracts reveal about nursing education and patient safety. Canadian Nurse, 105(8), 20–25.

Hall, M. (2013). An expanded look at evaluating clinical performance: Faculty use of anecdotal notes in the US and Canada. Nurse Education in Practice, 13, 271–276.

Heaslip, V. & Scammel, J. (2012). Failing under-performing students: The role of grading in practice assessment. Nursing Education in Practice, 12(2), 95–100.

Hodgson, P., Chan, K. & Liu, J. (2014). Outcomes of synergetic peer assessment: first-year experience. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(2), 168–179.

Kajander-Unkuri, S., Meretoja, R., Katajisto, J., Saarikoski, M., Salminen, L., Suhonene, R. & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2013). Self-assessed level of competence of graduating nursing students and factors related to it. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 795 – 801.

Keary, E. & Byrne, M. (2013). A trainee’s guide to managing clinical placements. The Irish Psychologist, 39(4), 104–110.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Knowles, M. (1975). Self-directed learning. New York: Association Press.

Larocque, S. & Luhanga, F. (2013). Exploring the issue of failure to fail in a nursing program. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 10(1), 1–8.

Loughran, J. J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33-43.

Lyons, N. (2006). Reflective engagement as professional development in the lives of university teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12(2), 151–168.

McBrien, B. (2007). Learning from practice–reflections on a critical incident. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 15(3), 128-133.

Marsh, S., Cooper, K., Jordan, G. Merrett, S., Scammell, J. & Clark, V. (2005). Assessment of students in health and social care: Managing failing students in practice. Bournemouth, UK: Bournemouth University Publishing.

Mass, M., Sluijsmans, D., Van der Wees, P., Heerkens, Y., Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. & van der Vleuten, C. (2014). Why peer assessment helps to improve clinical performance in undergraduate physical therapy education: A mixed methods design. BMC Medical Education, 14, 117.

Mehrdad, N., Bigdeli, S. & Ebrahimi, H. (2012). A comparative study on self, peer and teacher evaluation to evaluate clinical skills of nursing students. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Science, 47, 1847–1852.

Melrose, S. & Shapiro, B. (1999). Students’ perceptions of their psychiatric mental health clinical nursing experience: A personal construct theory explanation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30(6), 1451–1458.

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., Kemp, J. E., & Kalman, H. (2013). Designing effective instruction (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Mort, J. & Hansen, D. (2010). First-year pharmacy students’ self-assessment of communication skills and the impact of video review. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(5), 1–7.

O’Connor, A. (2015). Clinical instruction and evaluation. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Oermann, M. (2015). Teaching in nursing and role of the educator. New York: Springer.

Pisklakov, S., Rimal, J. & McGuirt, S. (2014). Role of self-evaluation and self-assessment in medical student and resident education. British Journal of Education, Society and Behavioral Science, 4(1), 1–9.

Ramani, S. & Krackov, S. (2012). Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Medical Teacher, 34, 787–791.

Ramli, A., Joseph, L. & & Lee, S. (2013). Learning pathways during clinical placement of physiotherapy students: A Malaysian experience of using learning contracts and reflective diaries. Journal of Educational Evaluation in the Health Professions, 10, 6.

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education. London: Routledge.

Regehr, G. & Eva, K. (2006). Self-assessment, self-direction, and the self-regulating professional. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 449, 34–38. Retrieved from http://innovationlabs.com/r3p_public/rtr3/pre/pre-read/Self-assessment.Regher.Eva.2006.pdf

Rudland, J., Wilkinson, T., Wearn, A., Nicol, P., Tunny, T., Owen, C. & O’Keefe, M. (2013). A student-centred model for educators. The Clinical Teacher, 10(2), 92–102.

Rush, S., Firth, T., Burke, L. & Marks-Maran, D. (2012). Implementation and evaluation of peer assessment of clinical skills for first year student nurses. Nurse Education in Practice, 12(4), 2219–2226.

Rye, K. (2008). Perceived benefits of the use of learning contracts to guide clinical education in respiratory care students. Respiratory Care, 53(11), 1475–1481.

Scales, D. E. (1943). Differences between measurement criteria of pure scientists and of classroom teachers. Journal of Educational Research 37, 1–13.

Scanlan, J. & Care, D. & Glessler, S. (2001). Dealing with the unsafe student in clinical practice. Nurse Educator, 26(1), 23–27.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Secomb, J. (2008). A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(6), 703–716.

Seldin, P. (1997). The teaching portfolio: A practical guide to improved performance and promotion/tenure decisions (2nd ed.). Bolton, MA: Ankor.

Shulman, L. (1998). Teacher portfolios: A theoretical activity. In N. Lyons (Ed.). With portfolio in hand: Validating the new teacher professionalism. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sluijsmans, D., Van Merriënboer, J., Brand-gruwel, S. & Bastiaens, T. (2003). The training of peer assessment skills to promote the development of reflection skills in teacher education. Studies in Education Evaluation, 29, 23–42.

Stark, P. B. (2014, September 26). An Evaluation of Course Evaluations. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://www.specs-csn.qc.ca/site-com/qlp/2015-2016/2016-03-30/articles.pdf

Timmins, F. (2002). The usefulness of learning contracts in nurse education: The Irish perspective. Nurse Education in Practice, 2(3), 190–196.

Walsh, T., Jairath, N., Paterson, M. & Grandjean, C. (2010). Quality and safety education for nurses clinical evaluation tool. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(9), 517–522.

Weeks, B. & Horan, S. (2013). A video-based learning activity is effective for preparing physiotherapy students for practical examinations. Physiotherapy, 99, 292–297.

Welsh, P. (2014). How first year occupational therapy students rate the degree to which anxiety negatively impacts on their performance in skills assessments: A pilot study at the University of South Australia. Ergo, 3(2), 31–38. Retrieved from http://www.ojs.unisa.edu.au/index.php/ergo/article/view/927

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems Thinker, 9(5), 2-3.

Winstrom, E. (n.d.). Norm-referenced or criterion-referenced? You be the judge! [Fact sheet]. Retrieved from http://www.brighthubeducation.com/student-assessment-tools/72677-norm-referenced-versus-criterion-referenced-assessments/?cid=parsely_rec