9 Victoria

Victoria

Dir. Sebastian Schipper, 2015

IMDb entry – trailers, cast & crew, trivia, and more

Reviews:

Victoria’s One Shot

Much is made of the way Victoria was made – a continuous, unbroken shot of 134 minutes. Many reviewers find it intriguing, if gimmicky: you can’t help but admire the technical and logistical audacity of Schipper’s undertaking, but you have to wonder if the film has anything going for it beyond the one shot wonder. The use of the one shot in the film isn’t gratuitous, however. The rush of this film is the rush in which it is made and presented. As Victoria gets swept up in the events of a fated misadventure, the viewer experiences some of that excitement (and panic) thanks to the non-stop nature of the one shot. Only twice during the film – as Victoria and her new-found friends go up to the rooftop of the apartment building, and when they return to the club after the robbery – does the film’s pacing slow dramatically thanks to non-diegetic “soundovers” that act like aural montage scenes, although instead of condensing time and activity, they give the viewers a moment to catch their breath and reflect on what is going on. There are other scenes where the pacing slows as well, most notably at the cafe when Victoria and Sonne are alone, but these scenes contribute to the narrative, whereas the “soundovers” eliminate the need to pay attention to plot.

Victoria and Genre

Moss and Wilson, in their book Film Appreciation, say the following about film genre:

Genre refers to the way in which films are categorized or marketed by film studios and the expectations that such categories bring to bear on the cinema spectator themselves. Film theorist Rick Altman defines genre in terms of its predictability and repetition of situations, themes and icons. So genre can be examined in terms of its structural conventions (expectations of plot, character, setting or style), thematic codes (for example, the themes of social corruption and infection contained in the zombie flick) or iconography (objects that instantly denote genre such as cowboy hats within the Western). Audience pleasure in genre stems from the familiarity of repetition, but it also stems from the ways in which films deviate from the expected script. We both want to know what to expect from a film and we also want to be surprised, to have our expectations exceeded. While audiences might choose to view a film based on expectations and familiarity with the particular genre, a director can surprise the audience by manipulating these genre expectations. Audience pleasure in genre stems from the familiarity of repetition, but it also stems from the ways in which films deviate from the expected script.

Victoria is often pegged as a heist film, but as such it’s maybe not a very good one: the heist doesn’t dominate the film from the outset, the way one sees in classics of the genre like Ocean’s Eleven (2001) or The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974). In fact, we don’t even see the actual heist. The lads go into the bank, but the camera remains with Victoria as she in frustration tries to restart the stolen getaway vehicle. But that doesn’t mean that Victoria doesn’t connect to the heist genre and some of its other occasional expectations: the botched job, the romance within the gang, the redemption or release that comes when the job is finally complete.

Of course, being set entirely in Berlin, and with Berlin being used as the set for the film, Victoria can also be classified as a Berlin film. But just as there are different kinds of heist films, there are also different kinds of Berlin films. Crime has often been a focus of the Berlin film, and a couple of classic Berlin films – M (1931) by Fritz Lang and Lola rennt (= Run Lola Run) (1998) by Tom Tykwer – share with Victoria an affinity for the streets of Berlin, a throwback perhaps to the street films of the 1920s (a genre M was both celebrating and changing when it was made in the early 1930s). Jan-Ole Gerster’s Oh Boy (= A Coffee in Berlin) from 2012 also sees the nearly penniless protagonist wandering through Berlin over the period of a day, though he’s not trying to commit a crime, he’s just trying to find a cup of coffee and figure his life out.

Another set of Berlin films will highlight the city’s famous landmarks, in particular those that remind us of the city’s place at the nexus of some of the twentieth century’s most important and horrendous geopolitical events. Der Himmel über Berlin (= Wings of Desire), Wim Wenders’s 1987 masterpiece, lets us see both sides of the Berlin Wall as well as a close-up of the angel at the top of the city’s Victory Column. Contemporary spy thrillers set partially in Berlin will often give us a glimpse of such sites as the tv tower on Alexanderplatz or the Brandenburg Gate in order to mark for the viewer the location of the action, just as they would show the Eiffel Tower for scenes set in Paris or Big Ben for those taking place in London.

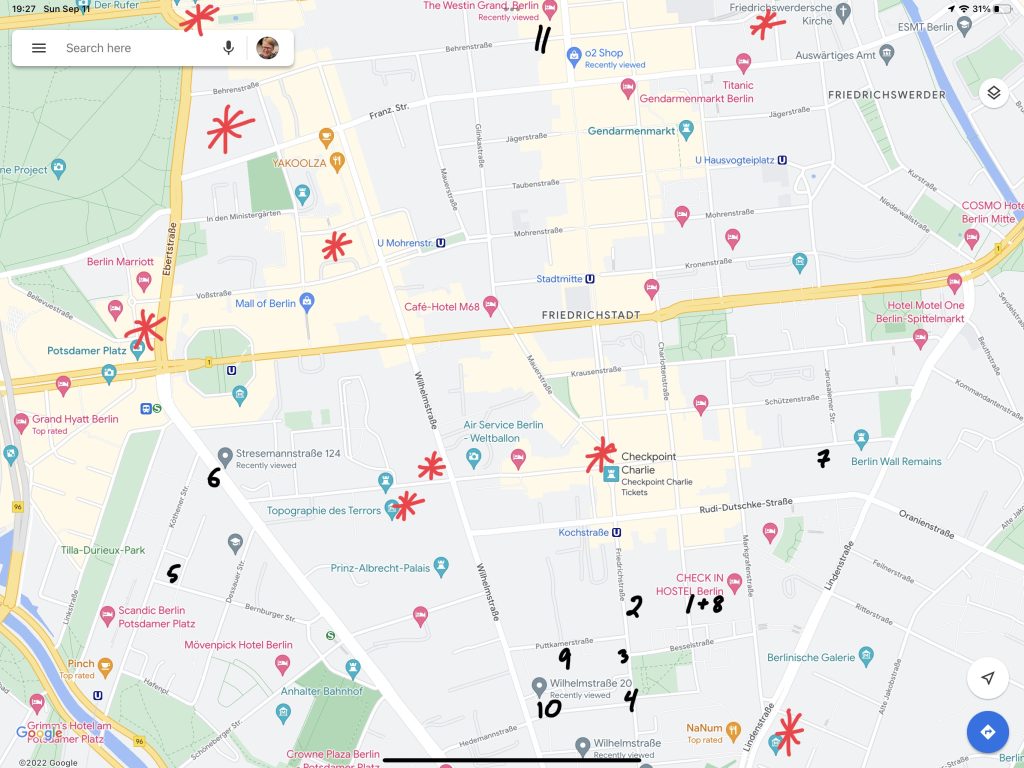

What’s intriguing about Victoria is that even though the film is set in an area of Berlin full of sites of significance in the history of the Third Reich and the Cold War, sites that are on the sightseeing agendas of many tourists who come to the city, the film rarely gives us any glimpse of them and never acknowledges them. To illustrate this, I’ve created a map that indicates the where the action of the film takes place (the numbered sites are where the characters stop for some amount of time) as well as important historical/tourist sites (red asterisks):

During the drive from the underground parking lot (#5) to the bank (#7), the hapless crew stop briefly to steel their nerves (#6). The route from there to the bank takes them past the Topographie des Terrors, the museum situated at the former headquarters of the Gestapo, and right through Checkpoint Charlie, a former entry point along the Berlin Wall. But we as viewers never notice these sites, and the camera is loathe to even acknowledge them.

If the film’s one shot technique keeps the pace of the action at a fever pitch, it also fits well with a film that refuses to acknowledge the past and is set entirely in the now.

Student Questions

In preparation for the lecture on Victoria, students of VCULT 100/FINE 102 – World Cinema and Visual Culture – are invited to submit questions. Some of those questions are answered in the material above, but this is a large course, and we get a lot of questions, so here’s a short list of other questions that haven’t been addressed yet, along with some brief answers.

What was the process for making the film in one shot?

Let’s let the director and star answer that question. The interview below goes into various details about the film, but the portion from about the 8.00 to about the 12.00 minute mark gets at the heart of the matter:

I know Victoria is a one-shot film, which means it only contains one long shot. And there are almost no clips in the film. But during the part where Victoria and a few others run away from the police, the screen frequently goes black and then switches to another scene. Is this a violation of the definition of a one-shot film?

In those brief moments you’ll see that the screen goes dark because the camera is keeping pace with the fleeing bank robbers. It sometimes gets to close to objects which causes the screen to go dark.

I’d like to know how much of this movie was scripted and how much was improvised, seeing as it was all done in one take. And I’d be curious to know how that compares to most other movies.

The “script” was a story outline 12 pages in length; the English translation provided to Laia Costa (who played Victoria) was only three pages long. So almost all of the dialogue was improvised. The plot of the film was divided into chunks of about 10 minutes in length, and the actors knew what was to happen in each of those chunks, but they were given the freedom to speak in character without set lines. This improvisation is almost like the script equivalent of the one shot filming technique: it gives the film a raw, natural feel. Most films are scripted, and that “scriptedness” aims at a different effect: a constructed, polished work of art that is very intentional in its attempt to move or entertain the viewer.

Why was the pace of the movie so slow? What else could they have done to make the movie more intriguing and fun to watch?

One person’s “slow film” is another person’s “well-paced” film. Pacing is a matter of expectation. If we are expecting an action movie involving a bank robbery, for example, we might think the narrative will move along at a quick clip. Students commented that the film felt slow at the beginning – was it really necessary, as one student pointed out, to open the film with a three-minute shot of Victoria dancing? My response is that whenever we come across something in a film that we find odd or unexpected or even irritating, we should take a moment to think about why we are surprised or annoyed. Could the filmmakers have a reason for doing what they’ve done? Does our annoyance have something to do with how we’ve been socialized into watching film? For example, is most of the filmed entertainment we watch fast-paced, and so when we come across something that is a slower, we find ourselves unnerved by it? From there we should ask ourselves what the director/filmmakers might be attempting to accomplish with this kind of pacing.

A number of students commented on the colour palette of the film. Shot at night, it’s not unexpected that there would be a lot of cool blue tinting to the film, which contrasted with the warm yellows that were prevalent in the café scene. Later in the film, during and after the bank robbery, the blues were seen to dominate. How was this effect achieved, was it intentional?

Hard to answer that without speaking to the film crew directly. The streets scenes appear to have been lit with available lighting only, which gives those passages of the film a realist, almost grainy appearance. Indoor scenes, such as in the café, may have had some additional lighting, but since we do get a fairly wide shot of the café and don’t see any lighting equipment, I think we can hazard the guess that the cafe’s lighting was not cinematically enhanced (although colour correction and adjustments surely occurred in post-production). It’s not that the colours signify anything in and of themselves, but the contrast of lighting colour is a visual cue for viewers to take note of something; when most of the film has a bluish tinge, and then a scene occurs where yellow dominates, that scene will be more memorable.

Was there any significance to Victoria tying up and re-tying her hair? I noticed that there were multiple instances where the scene focused on this detail and I was wondering if this had some sort of deeper meaning. This could just be because it is a one-shot film and small details like this could not be cut away from, but it is a small point that stuck in my mind.

I don’t think there’s any significance per se. In a more scripted film you would be unlikely to see an actor playing with their hair as much as Victoria does, unless doing so had a connection to the plot or character is some significant fashion. Instead, I’d read it as a fairly normal activity of a person of Victoria’s age who often fusses with her hair. I suppose one could argue that this might speak to Victoria’s character (indicating nervousness or anxiety), but it could also simply be a natural enough gesture imitated by countless people.

But others disagree with me. Take for example what Myrto the TA writes: Victoria seems to untie her hair during moments in the story that she feels out of danger and can let go, for instance when she sits down with the boys on the rooftop (00:26:25) or when she’s at the club after the heist (01:34:00), and then re-tie it when she senses she might be in danger again, for instance when she sees the police cars after getting out of the club following the heist (01:38:05) or when she’s about to approach the hotel reception at the end of the film (01:56:38). This might not be exclusively intentional on Schipper’s or Costa’s part, but there is some consistency to both gestures that supports this interpretation.

I am wondering how different people’s opinions about the movie would be if no subtitles had been available and we, like the main character, were out of the loop. It would add to the theme of isolation but at the cost of being constantly confused.

Whenever we watch a movie, we can ask ourselves to what extent do we fall down the rabbit hole of the film and become completely immersed in the story. Are there elements to the filmmaking itself that keep us falling down that hole? Subtitles are one such element; they remind us we’re watching a story, not participating in one. It would be possible to present this film without subtitles, and that’s done sometimes for the very reason you suggest, to keep the viewers out of the loop just like some characters in a film. But that is very alienating, and most filmmakers and distributors would want to avoid that. So subtitles are kind of unavoidable.

Another point to make about subtitles: if you know the language being spoken, you’ll often be disappointed by the subtitles. Subtitles are almost often always abridged; it takes longer to read dialogue than to listen to it, so the subtitles have to be as concise as possible or else they’ll get out of sync with the dialogue. Moreover, there are some expressions that just don’t translate well, and yet there’s no space or time to explain more fully what’s being said.

Are women statistically, generally, safer in Spain/Germany than here in Canada? If so, is that why Victoria thought it was fine to go with some random men she just met? Maybe that could be attributed to poor street smarts, but I’m genuinely curious.

I tried looking into some statistics on this, but haven’t found anything yet. Women are victims of assault the world over, and certainly in a city like Berlin assault can take place. I think what’s more interesting is what this says about Victoria as a character that she would tag along with this group. During the film we learn that she’s new to Berlin and doesn’t know anyone, and perhaps that’s enough reason to suspend disbelief on the part of the audience about how risky her behaviour is?

There were a number of questions along these lines: Do you find Victoria’s willingness to go along with the heist and the events that follow realistic?

As with the answer above, I think it’s sometimes important to suspend disbelief and let the film take us where it wants to take us. Many characters in stories and films do things that I would never dream of doing: reading about or seeing what happens to them is part of the fun of reading/watching fiction. Since we know so little about Victoria in the first place, watching her follow along isn’t implausible; we don’t know enough about her to know why she would object to participating. Our surprise about her willingness to be dragged along might speak more to our sense of ourselves than our sense of Victoria.

One can also argue that the first scene in the film establishes Victoria’s loneliness, isolation, and search for connection. She speaks with the bartender and even offers to buy him a drink. Later, her willingness to go along with the heist is the final link in a chain of small decisions she has made up until this point in order to get to know Sonne, given that she has no other friends in the city and finds it difficult to connect with people, as the first scene establishes. Add to that the fearlessness/recklessness that we see when Victoria is on the rooftop (see below), and perhaps her willingness to go along with the heist doesn’t seem too far-fetched.

Something that I didn’t really understand is how Victoria wanted to stand on the ledge of the roof so easily. For me it seemed that there was some reasoning behind this decision, whether that was her wanting to “let loose” and enjoy the night or something that is much bigger.

I’m personally afraid of ledges, and whenever I watch that scene I get nervous! I view it as an indicative of Victoria’s fearlessness. I don’t mean that as a compliment, but just as a statement of fact: she appears oblivious to the riskiness of what she’s doing. This character trait might also help explain her actions in the rest of the film.

I would like to know where Victoria is going at the end of the movie? Is she walking back to the coffee shop?

That’s the million dollar question. The ending of the film is mostly a closed one – we know that the heist is over – but it’s also still slightly open: as Victoria walks away from the hotel, the camera stops in the middle of the street, and Victoria continues along Behrenstrasse, slowly receding from view. We almost expect the police to finally catch up to her and arrest her, but that doesn’t happen, and so we can only speculate, based on what we’ve learned about her in the film, as to where she’s going, both now in this moment and in her life.