Understanding Play

“Through play and inquiry, young children practice ways of learning and interacting with the world around them that they will apply throughout their lives. Problem-solving and critical thinking, communication and collaboration, creativity and imagination, initiative and citizenship are all capacities vital for success throughout school and beyond.” (How Does Learning Happen? p.15)

Children are born observers and are active participants in their own learning and understanding of the world around them from the very beginning of their existence. Today’s children are active participants in their own learning, not just recipients of a teacher’s knowledge.

Indigenous Perspectives

People of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy are committed to lifelong learning. Adults understand they have a responsibility to their children to facilitate an environment where reciprocal learning occurs. Children and Elders learn from each other, and each are respected for their contributions and gifts

1.1 Why Play?

“As children learn through play and inquiry, they develop – and have the opportunity to practice every day – many of the skills and competencies that they will need in order to thrive in the future, including the ability to engage in innovative and complex problem-solving and critical and creative thinking; to work collaboratively with others; and to take what is learned and apply it in new situations in a constantly changing world.” (The Kindergarten Program, 2016, p.11)

In its “Statement on Play-Based Learning,” CMEC (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada). (2012), recognizes the educational value of play as follows:

The benefits of play are recognized by the scientific community. There is now evidence that neural pathways in children’s brains are influenced by and advanced in their development through the exploration, thinking skills, problem-solving, and language expression that occur during play.

Research also demonstrates that play-based learning leads to greater social, emotional, and academic success. Based on such evidence, ministers of education endorse a sustainable pedagogy for the future that does not separate play from learning but brings them together to promote creativity in future generations. In fact, play is considered so essential to healthy development that the United Nations has recognized it as a specific right for all children.

Given the evidence, the CMEC believes in the intrinsic value and importance of play and its relationship to learning. Educators should intentionally plan and create challenging, dynamic, play-based learning opportunities. Intentional teaching is the opposite of teaching by rote or continuing with traditions simply because things have always been done that way. Intentional teaching involves educators’ being deliberate and purposeful in creating play-based learning environments – because when children are playing, children are learning.

Play:

- Inspires imagination

- Facilitates creativity

- Fosters problem solving

- Promotes the development of new skills

- Build confidence and higher levels of self-esteem

- Allows free exploration of the environment

- Fosters learning through hands-on and sensory exploration

It is now understood that moments often discounted as “just play” or as “fooling around” are moments in which children are actively learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2009; Jones and Reynolds 2011; Zigler, Singer, and Bishop-Josef 2004; Elkind 2007.) While engaged in play, children explore the physical properties of materials and the possibilities for action, transformation, or representation. Children try out a variety of ways to act on objects and materials and, in so doing, experiment with and build concepts and ideas. This active engagement with the world of people and objects starts from the moment of birth.

This description of the young child as an active participant in learning informs the role of the teacher who works with young children from birth to five. Early childhood teaching and learning begins with teachers watching and listening to discover how infants and young children actively engage in making sense of their everyday encounters with people and objects. When teachers observe and listen with care, infants and young children reveal clues about their thinking, their feelings, or their intentions. Children’s actions, gestures, and words illuminate what they are trying to figure out and how they attempt to make sense of the attributes, actions, and responses of people and objects. Effective early childhood teaching requires teachers to recognize how infants and young children actively search for meaning, making sense of ideas and feelings.

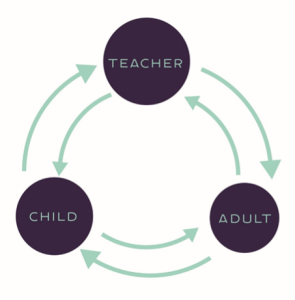

When teaching is viewed in this light, children become active participants alongside teachers in negotiating the course of the curriculum. Families who entrust their children to the care and guidance of early childhood teachers also become active participants in this process. Shared participation by everyone in the work of creating lively encounters with learning allows a dynamic exchange of information and ideas—from child to adult, from adult to child, from adult to adult, and from child to child. The perspective of each (child, family, teacher) informs the other, and each learns from the other. Each relationship (child with family, child with teacher, child with child, and family with teacher) is reciprocal, with each participant giving and receiving from the other, and each adding to the other’s learning and understanding. (California Department of Education, p.5)

Indigenous Perspective

The Cornhusk doll is still used today by Haudenosaunee children. The teaching that accompanies the corn husk doll provides an opportunity for adults to interact in a meaningful way with children. The children practice essential relationship skills by providing holistic care for their doll using a combination of creative and dramatic play that reflects their understanding of family roles and responsibilities.

For more information on the teachings related to Corn Husk Dolls, see the link at the end of this chapter.

In Ontario, The Kindergarten Program (2016) sets out five fundamental principles of play-based learning:

- Play is recognized as a child’s right, and it is essential to the child’s optimal development.

- All children are viewed as competent, curious, capable of complex thinking, and rich in potential and experience.

- A natural curiosity and a desire to explore, play, and enquire are the primary drivers of learning among young children.

- The learning environment plays a key role in what and how a child learns.

- In play-based learning programs, assessment supports the child’s learning and autonomy as a learner

Recent brain research has heralded the benefits of a stimulating play-based environment in encouraging the brain to grow and develop (Diamond 1988). Low-stress levels and high engagement combine to nourish neural development. Research by Vandell and others (2005) demonstrates how school-aged care environments achieve this through the combination of high intrinsic motivation and challenge, effort, and enjoyment. Lester and Russell (2010) identified the flexibility and plasticity of the brain, which develops through play and increases the potential for learning later in life.

The intellectual and cognitive benefits of playing have been well documented. Children who engage in quality play experiences are more likely to:

- Have well-developed memory skills and language development,

- Can regulate their behaviour, leading to enhanced adjustment to school and academic learning.

Play also provides children with an opportunity to just be. Educators observe stages of play experiences children navigate in their programs. Educators use these observations of children to plan for environments, set individual objectives, and create appropriate curricular experiences.

Pause to Reflect

What does it mean to just be? Consider a time either as a child or an adult, where you had an opportunity to just be.

What facilitated the opportunity?

What feelings did you experience?

What might this mean for young children?

1.2 History of Play

“Play lies at the core of creativity and innovation. Of all animal species, humans are the biggest players of all. We are built to play and built through play. When we play, we are engaged in the purest expression of our humanity, the truest expression of our individuality” (Brown, 2010).

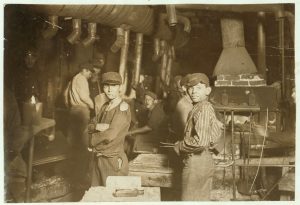

The importance of and value placed on childhood play can be traced all the back to ancient civilizations (500 BC to 500 CE). Ancient Egyptians understood that play influenced later development. However, during the Middle Ages (900-1200), ensuring children simply survived became much more important than providing developmental opportunities. Children were treated like adults as they were needed in the labour force. The Renaissance Period (1200-1700) ushered in a renewed belief that childhood was distinct from adulthood and that play had value. Learning through play continued to be valued into the Modern Period (1700-1900), even though child labour continued to be common during the Industrial Revolution (1750-1840). During the late 20th century (1950-1999), “Research found that children develop in predictable stages, that the environment and genetic inheritance are both instrumental, and that children construct. knowledge and intellect by doing” (Shipley, 2012, p.21). 21st century researchers continue to build on this foundational research, expanding our understanding of play theory and early learning.

1.3 Theories of Play

Barnard Gilmore (1966) proposed there are two categories of play theory: classical theories and dynamic theories. Classical theories (17th century to late 19th century) attempted to explain why people play while dynamic theories (20th century onward) attempt to explain how people play. Dynamic theories can be further categorized into psychoanalytic theories and developmental theories.

Classical Theories

- Surplus energy theory: energy not needed for work can be spent in play.

- Relaxation theory: play generates energy for work.

- Pre-exercise theory: play as practice for future roles in society.

- Recapitulation theory: children’s play looks like the behaviour of people from an earlier time. (Shipley, 2012, p.22)

Dynamic Theories

Psychoanalytic Theories

Freud (1856-1939): Freud believed that play gives children a way to express inner feelings they are unable to verbalize.

Erikson (1902-1994): Erikson believed that play develops physical and emotional skills that contribute to the development of healthy self-esteem.

Developmental Theories

Piaget (1896-1980): Piaget believed that play is a tool for consolidating new information and behaviours.

| Stage | Description |

| Functional Play (birth to 18 months) | Exploring, inspecting, and learning through repetitive physical activity |

| Symbolic Play (2-4 years) | The ability to use objects, actions, or ideas to represent other objects, actions, or ideas and may include taking on roles. |

| Constructive Play (4-7 years) | Involves experimenting with objects to build things; learning things that were previously unknown with hands on manipulations of materials. |

| Games with Rules (6-11 years) | Imposes rules that must be followed by everyone that is playing; the logic and order involved forms that the foundations for developing game playing strategy. |

Vygotsky (1896-1934): Vygotsky shared many of Piaget’s principles about the value of play; however, he placed more emphasis on the importance of the social interactions between children and more experienced adults that can result in learning through play and guided discovery.

Postmodern Views (1980-current)

Many postmodern theorists (e.g.: Kohlberg, Gardner, Malaguzzi, Mustard) questioned earlier theories that children’s play is universal and independent of cultural influences. They believe that “There are really two approaches to raising and educating children: a middle class, Eurocentric American approach, and a minority approach (Johnson et al., 2005). The postmodern perspective believed that play serves the goals of Western society that foster independence, competitiveness, power, and domination in children. Play was seen by non-Western cultures as frivolous and incompatible with values of group loyalty, obedience, respect for elders, co-operation and collectivism” (Shipley, 2012, p.31).

Indigenous Perspectives

Play for many Indigenous nations involves role-playing to learn what their responsibilities will be as an adult. For example, the game of lacrosse was traditionally a men’s game that allowed them to develop their stealth and agility skills to be a good hunter. Today, lacrosse is enjoyed by both men and women but skill development still begins very early allowing their abilities to mature over time.

The Play vs Structure Debate

Giving children the freedom to direct their own play is an idea that goes all the back to the philosophy Jean-Jacque Rousseau (1712-1778). Over the next 300 years, this belief fell in and out of favour.

The term “free play” was introduced early in the 20th century. Patty Smith Hall (1868-1946) defined “free play” as follows: “In free play, the self makes its own choices, selections, and decisions, and thus absolute freedom is given to the play of the child’s images and volition in expressing them” (Shipley, 2012, p.59-60)

In the 1960s and 1970s, any structure in programs for young children was frowned upon. (Shipley, 2012, p. 59). The pendulum swung back slightly during the 1980s when educators such as David Weikart (1931-2003) advocated that some structure was appropriate to enhance the benefits of play.

The early 1990s ushered in a new emphasis on the importance of the development of children’s self-esteem as a curriculum goal. Children were seldom held back in school for not achieving academic goals. Pedagogical practice was praising children for their efforts, not the result. This approach was labelled “child-centered education.” Unfortunately, it became incorrectly interpreted as having lower expectations for children. This misinterpretation resulted in the “back to basics” movement that was based on an unsupported linkage between poor results on standardized tests and child-centered education.

In the late 1990s, the Reggio Emilia Approach gained prominence as a successful child-centered, constructivist, curriculum model. This approach balances “both sides of the play versus structure issue, an influence that restored the credibility of developmental skills as viable outcomes and play-based intervention to help children achieve them.” (Shipley, 2012, p.60)

Increasing globalization in the 2000s has renewed the interest of parents in early academic success for their children. It is common for parents to ask Early Childhood Educators “Why do you let the children play all day?” Early Childhood Educators must:

- be knowledgeable about the value of play

- be able to clearly explain the developmental outcomes that children are achieving through play

- be able to make learning visible through documentation.

“Learning success for the information age emphasizes the ability to perform complex tasks and roles.” (Shipley, 2012, p.63). 21st century skills that are developed during play include:

- Making choices

- Staying focused for extended periods of time

- Demonstrating understanding

- Social skills such as entering a group, negotiating roles, collaborating with others

- Using divergent thinking skills to solve problems

- Assessing risk

Pause to Reflect

Play activities for children have always been associated with teachings for the Haudenosaunee people and other Indigenous nations of Canada. It provided an opportunity for adults to relay important life lessons to children during their development. This is a practice that continues today.

Take a moment to reflect on how colonization and in particular, the residential school system and sixties scoop negatively affected this important transfer of knowledge from generation to generation.

The Diversity of Beliefs About and Practices of Play

In an extensive and thorough review of international research on adults’ beliefs about play, children’s play with parents, and children’s own play conceptualizes play as “both culturally framed and unframed activities that are subsumed under the umbrella of ‘playfulness’”.

“As distinguished from conventional definitions of play, playfulness is a more universal phenomenon and includes childhood and parent-child unframed play activities that co-occur during caregiving and in children’s encounters with different individuals and objects within specific developmental niches.” (Roopnarine, 2011)

When children (or adults) introduce playfulness into what has been initiated as activities other than play, they in fact, at least temporarily, reframes the activity as play(ful). Research has shown that parents differ in their view of the merits of play (Roopnarine, 2011). Parents from what is referred to as European or European- heritage cultures, and particularly among higher-educated middle-class backgrounds, differ in being positive to “‘concerted cultivation’ during socialization (constantly coaching, creating opportunities) compared to low-income families who believe that children naturally acquire certain skills”, including play support. Regarding the latter, there was a positive relationship between play support and parental education, and an inverse relationship between parental education and academic focus, suggesting that parents with higher levels of educational attainment were more likely to endorse play as a means for learning early cognitive and social skills than those with lower levels of educational attainment.

That is, higher-educated parents are more positive to play as a means of facilitating children’s development – and children’s development more generally than promoting particular learning outcomes – than lower-educated parents. Among the latter group, “economic and social pressures may lead parents to choose didactic approaches over play in early education in order to minimize the risk of attendant to school failure later on” (Roopnarine, 2011). It is important to realize that what is here referred to as ‘didactic approaches’ denote practices based on traditional school instruction,

Not surprisingly, but importantly, variation in parental beliefs concerning the value of play corresponds with the frequency, nature and quality of parent-child play, with parents in European and European-heritage communities engaging, for example, in playful activities with children and objects in ways that involve labeling more than parents with other cultural backgrounds.

Unfortunately, the lay view that play is not serious, and thus not important to ‘real’ education, is still all too common. In their extensive review of studies on play in education, Fisher, Hirsch-Pasek, Golinkoff, Singer, and Berk deduce this controversy to a more long-standing debate on how children learn. They argue that historically there are two traditions to this question, what they refer to as “the ‘empty vessel’ approach” and “the whole-child perspective” respectively.

The Empty Vessel Approach

Arising from behaviourist philosophies, some believe that there is a core set of basic skills that children must learn and a carefully planned, scripted pedagogy is the ideal teaching practice. In this ‘direct instruction’ perspective, teachers become agents of transmission, identifying and communicating need-to-know facts that define academic success. Learning is compartmentalized into domain-specific lessons (mathematics, reading, language) to ensure the appropriate knowledge is being conveyed. Worksheets, memorization, and assessment often characterize this approach – with little academic value associated with play, even in preschool.

The Whole Child Approach

In contrast to the empty vessel approach, described by Fisher et al., they present what they refer to as the whole-child approach, in which children themselves are ascribed an active role in their learning, where meaningfulness is critical, and “play, in particular, represents a predominant method for children to acquire information, practice skills, and engage in activities that expand their repertoire”. A recurring concept in discussions and theorizing emphasizing children’s active participation is agency.

In general, the field of early childhood education is most closely aligned with the whole-child approach. However, it is important to remember that making an “either/or” distinction between the two approaches is an oversimplification and one would not expect to find clear-cut examples of either approach. For example, the important roles of more experienced peers, particularly teachers, in children’s learning and development are sometimes miscommunicated. Rather than arguing for one or the other approach, it is critical to theorize teaching in play-based activities in more nuanced ways than what “either/or” choices allow.

Reviewing studies on play and learning, Fisher et al. conclude that “the findings show that play can be gently scaffolded by a teacher/adult to promote curricular goals while still maintaining critical aspects of play.” What they refer to as ‘playful learning’ consists of two parts: free play and guided play. The latter has two aspects: adults enriching children’s environment with toys and other objects relevant to a curricular domain (e.g., literacy), and adults playing along with children, including critically, asking questions and “the teacher may model ways to expand the child’s repertoire (e.g., make sounds, talk to other animals, use it to ‘pull’ a wagon)”. While children’s play provides the basis for this form of pedagogy, “teacher guidance will be essential”. Teacher guidance, as Fisher et al. point out, “falls on a continuum”, that is, the question is not whether or not the teacher participates (or should participate) but the extent to – and more critically, how.

The example of developing preschool children’s shape concepts can illustrate the merits of this form of pedagogy. In the study, children were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: guided play, direct instruction, or control condition. In the guided play condition, children were encouraged to “discover the ‘secret of the shapes’” and adults asked what the researchers refer to as ‘leading questions’, such as how many sides there are to a shape. In the instruction condition, in contrast, the adult verbally described the shape properties to the children. In the control, condition children listened to a story instead of engaging with shapes. Afterward, the children were asked to draw and sort shapes.

Results from a shape-sorting task revealed that guided play and direct instruction appear equal in learning outcomes for simple, familiar shapes (e.g., circles). However, children in the guided play condition showed significantly superior geometric knowledge for the novel, highly complex shape (pentagon) than the other conditions. For the complex shapes, the direct instruction and control conditions performed similarly. The findings suggest discovery through engagement and teacher commentary (dialogic inquiry) are key elements that foster and shape learning in guided play.

This research concluded there is no difference in learning outcomes between guided play and direct instruction when it comes to relatively simple content, but when it comes to more complex content, guided play outperforms direct instruction; in fact, as found, when it comes to complex content, direct instruction was no better than what the control group performed (i.e., in this case, direct instruction made no difference to learning outcomes, on a group level). As clarified by Fisher et al.’s reasoning, teacher participation is critical to the success of guided play, not least to engage children in talking about the matters at hand and how these may be understood.

Pause to Reflect

Haudenosaunee children learn through play and mimicking their parents. For example, a child may have a toy rattle and mimic their parents’ actions in a drumming circle. The parent guides the children’s actions to help them become more proficient and independent.

Is this an example of the “empty vessel” or “whole child” approach? Why?

Important Things to Remember

- Children are born observers and are active participants in their own learning and understanding of the world around them from the very beginning of their existence.

- There is now evidence that neural pathways in children’s brains are influenced by and advanced in their development through the exploration, thinking skills, problem solving, and language expression that occur during play.

- Play is considered so essential to healthy development that the United Nations has recognized it as a specific right for all children.

- Classical theories of play (17th century to late 19th century) attempted to explain why people play while dynamic theories of play (20th century onward) attempt to explain how people play.

- Culture influences how children’s play is viewed and valued.

- Play can be scaffolded by a teacher/adult to promote curricular goals while still maintaining critical aspects of play.

Supplemental Readings

References

Brown, S., with Vaughn, C. (2010). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. New York, NY: Avery (Penguin).

California Department of Education, The Integrated Nature of Learning is used with permission

CMEC (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada). (2012). “Statement on play-based learning.” Retrieved from: http://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/282/play-based-learning_ statement_EN.pdf

Diamond, M. C. (1988). Enriching heredity: The impact of the environment on the anatomy of the brain. Free Press.

Elkind, D. (2007). The power of play: How spontaneous imaginative activities lead to happier, healthier children. Da Capo Press.

Fisher, K., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Singer, D. G., & Berk, L. (2011). Playing around in school: Implications for learning and educational policy. In A. D. Pellegrini (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 341–360). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hirsch-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R., Berk, L., Singer, D. (2009). A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jones, E., Reynold, G. (2011). The Play’s the Thing: Teachers’ Roles in Children’s Play. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lester, Stuart & Russell, Wendy. (2010). Children’s Right to Play: An Examination of the Importance of Play in the Lives of Children Worldwide. Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Ministry of Education, Ontario. How Does Learning Happen? Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014

Roopnarine, J. L. (2011). Cultural variations in beliefs about play, parent-child play, and children’s play: Meaning for childhood development. In A. D. Pellegrini (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 19–37). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Shipley, D. (2012). Empowering Children: Play-Based Curriculum for Lifelong Learning, Nelson Canada.

The Kindergarten Program. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016.

Vandell, D., Pierce, K., Dadisman, K. (2005). Out-of-school settings as a developmental context for children and youth. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, Volume 33, 43-77. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2407(05)80004-7

Zigler, E. F., & Bishop-Josef, S. J. (2004). Play under siege: A historical overview. In E. F. Zigler, D. G. Singer, & S. J. Bishop-Josef (Eds.), Children’s play: The roots of reading (pp. 1–13). ZERO TO THREE/National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families.