Pedagogical Foundations and Models

“Pedagogy is about how learning takes place. Play is a child-centered activity that engages a young child and promotes learning (Berk & Winsler, 1995; Kagan & Britto, 2005; Kagan & Lowenstein, 2004; Greenspan & Shanker, 2004).

Play is how children make sense of the world and is an effective method of learning for young children. Ideas and skills become meaningful; tools for learning are practiced; and concepts are understood.

Play engages children’s attention when it offers a challenge that is within the child’s capacity to master. Early childhood settings that value children’s play create a ‘‘climate of delight” that honours childhood (ETFO, 1999). Effective settings take advantage of play and embed opportunities for learning in the physical environment and play activities.

Children who thrive in primary school and whose pathways are set for later academic success are those who enter Grade 1 with strong oral communication skills, are confident, able to make friends, are persistent and creative in completing tasks and solving problems and excited to learn (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Bennett, 2004; National Research Council, 2001; Sylva et al., 2004; Maggi et al., 2005). These are the same qualities that children strengthen through high-quality play during their early years.” (Excerpts from ELECT, p.9)

3.1 How Does Learning Happen? Foundations for Learning

“Pedagogical approaches that nurture learning and development in the early years include:

- establishing positive, responsive adult-child relationships.

- providing inclusive learning environments and experiences that encourage exploration, play, and inquiry

- engaging as co-learners with children, families/caregivers, and others.

- planning and creating environments as a “third teacher.”

- using pedagogical documentation as a means to value, discuss, and make learning visible.

- participating in ongoing reflective practice and collaborative inquiry with others.” (How Does Learning Happen? pg.16)

“Engagement suggests a state of being involved and focused. When children are able to explore the world around them with their natural curiosity and exuberance, they are fully engaged. Through this type of play and inquiry, they develop skills such as problem solving, creative thinking, and innovating, which are essential for learning and success in school and beyond.” (How Does Learning Happen? p.7)

- Research has proven that children learn best in environments that enable them to be fully involved in meaningful exploration, spontaneous play, and inquiry. (How Does Learning Happen? p.35.)

- Engagement is supported when educators are co-learners, valuing children’s ideas and contributions.

- The environment itself directly impacts children’s opportunities to become fully engaged in their play. A neatly organized assortment of open-ended materials encourages exploration and play. It is equally important to ensure children are given long periods of time to become fully engaged in their play.

“Expression or communication (to be heard, as well as to listen) may take many different forms. Through their bodies, words, and use of materials, children develop capacities for increasingly complex communication. Opportunities to explore materials support creativity, problem-solving, and mathematical behaviours. Language-rich environments support growing communication skills, which are foundational for literacy.” (How Does Learning Happen? p.8)

- Supportive early learning environments enable children to communicate and express themselves in a wide variety of forms.

- Children can communicate their thoughts and feelings verbally, non-verbally, and through creative expression.

- How Does Learning Happen? emphasizes the importance of valuing a child’s first language and culture as a means of expression.

Indigenous Perspective

The family structure of the Haudenosaunee involves extended family such as cousins, aunties, uncles, and grandparents. Through this family unit, a child is fully supported as they learn to explore their world. Children who are engaged by family members of a variety of ages develop the capacity to communicate on multiple levels including both verbal and non-verbal methods.

3.2 Developmentally Appropriate Practice

Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP), as outlined by NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children), challenges early childhood professionals to be intentional in their interactions and environments to create optimal experiences to maximize children’s growth and development. Under this umbrella of DAP, knowledge is based upon discovery and discovery occurs through active learning and abundant opportunities for exploration. Through a “hands-on” approach and using play as a vehicle, children will develop skills in domains necessary for growth and development.

Pause to Reflect

Consider your childhood. Were you presented with toys that were specific to a culture? We can find and intentionally include toys from other cultures that will spark new language and appreciation.

According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s Position Statement, “The core of developmentally appropriate practice lies in… intentionality, in the knowledge that practitioners consider when they are making decisions, and in their always aiming for goals that are both challenging and achievable for children.” To do this, they must use developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). DAP includes three areas of knowledge:

- Age-appropriateness – using what is known about child development and learning in general.

- Individual-appropriateness – using what is known about each child as an individual to be responsive to each child.

- Social- and cultural-appropriateness – using what is known about the social and cultural context in which children live. (NAEYC, 2019)

Head Start has guiding principles that reflect developmentally appropriate practice by an intentional teacher:

- Each child is unique and can succeed

- Learning occurs within the context of relationships.

- Families are children’s first and most important caregivers, teachers, and advocates.

- Children learn best when they are emotionally and physically safe and secure.

- Areas of development are integrated, and children learn many concepts and skills at the same time. Teaching must be intentional and focus on how children learn and grow.

- Every child has diverse strengths rooted in their family’s culture, background, language, and beliefs. (Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework)

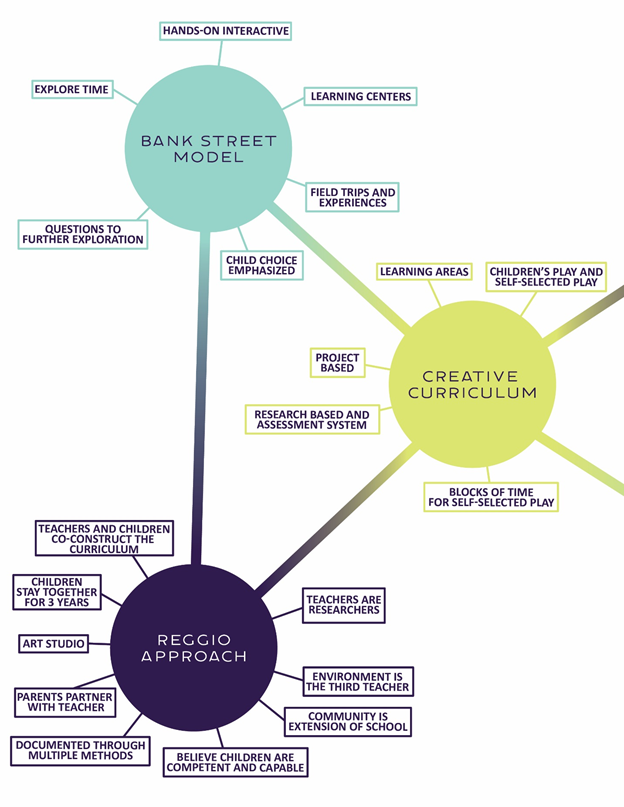

3.3 Bank Street Model

Lucy Sprague Mitchell founded Bank Street, an Integrated Approach, also referred to as the Developmental-Interactionist Approach.

In this model, the environment is arranged into learning centers and planning is organized using materials within the learning areas (centers).

- Art

- Science

- Sensory/Cooking

- Dramatic Play

- Language/Literacy

- Math/Manipulative/Blocks

- Technology

- Outdoors: Water and Sand Play

“A teacher’s knowledge and understanding of child development is crucial to this approach. Educational goals are set in terms of developmental processes and include the development of competence, a sense of autonomy and individuality, social relatedness and connectedness, creativity, and integration of different ways of experiencing the world” (Gordon, p.364)

3.4 Creative Curriculum Model (Diane Trister Dodge)

In the Creative Curriculum model, the focus is primarily on children’s play and self-selected activities. The Environment is arranged into learning areas and large blocks of time are given for self-selected play. This model focuses on project-based investigations as a means for children to apply skills and addresses four areas of development: social/emotional, physical, cognitive, and language.

The curriculum is designed to foster the development of the whole child through teacher-led, small, and large group activities centered around 11 interest areas:

- blocks

- dramatic play

- toys and games

- art

- library

- discovery

- sand and water

- music and movement

- cooking

- computers

- outdoors.

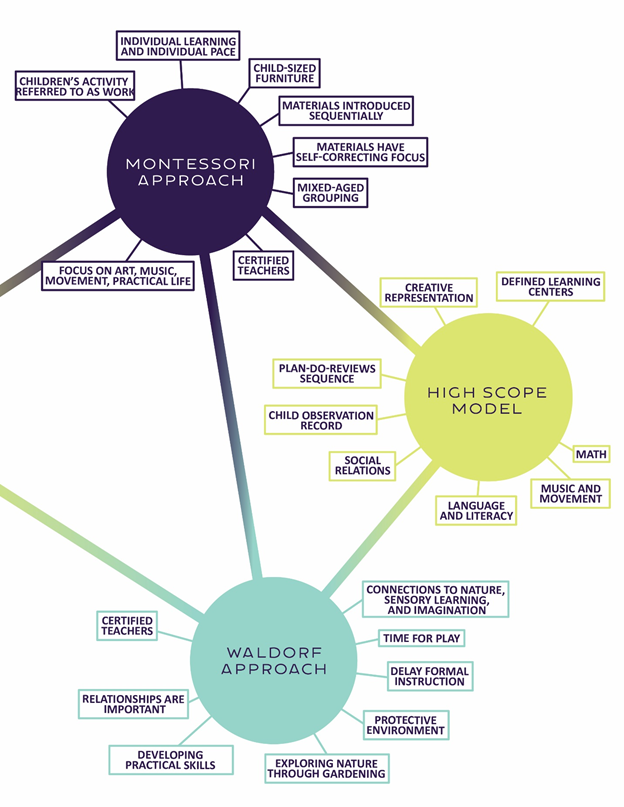

3.5 High Scope Model (David Weikert)

The High Scope Model focuses on developing learning centers like the Bank Street Model and emphasizes key experiences for tracking the development. The key experiences are assessed using a Child Observation Record for tracking the development and include areas of:

- Creative Representation

- Initiative

- Social Relations

- Language and Literacy

- Math (Classification, Seriation, Number, Space, Time)

- Music and Movement

3.6 Montessori Approach (Dr. Maria Montessori)

The Montessori Approach refers to children’s activity as work (not play); children are given prolonged periods of time to work and a strong emphasis on individual learning and the individual pace is valued. Central to Montessori’s method of education is the dynamic triad of child, educator, and environment. One of the educator’s roles is to guide the child through what Montessori termed the ‘prepared environment, i.e., a classroom and a way of learning that is designed to support the child’s intellectual, physical, emotional, and social development through active exploration, choice, and independent learning.

The educational materials have a self-correcting focus and areas of the curriculum consist of art, music, movement, and practical life (for example, pouring, dressing, and cleaning). In the Montessori method, the goal of education is to allow the child’s optimal development (intellectual, physical, emotional, and social) to unfold.

A typical Montessori program will have mixed-age grouping. Children are given the freedom to choose what they work on, where they work, with whom they work, and for how long they work on any activity, all within the limits of the class rules. No competition is set up between children, and there is no system of extrinsic rewards or punishments.

3.7 Waldorf Approach (Rudolf Steiner)

The Waldorf Approach, founded by Rudolf Steiner, features connections to nature, sensory learning, and imagination. The understanding of the child’s soul, of his or her development and individual needs, stands at the center of Steiner’s educational worldview.

The Waldorf approach is child-centered. It emerges from a deep understanding of child development and seeks to support the developmental tasks (physical, emotional, and intellectual) children face at any given stage. Children aged 3–5, for example, are developing a keen interest in the world, supported to a significant extent by freedom of movement, and must be supported to follow and deepen their curiosity through the encouragement of their sometimes endless asking of questions (Van Alphen & Van Alphen 1997). This approach to supporting children’s naturally blossoming curiosity, rather than answering the educators’ questions. At this stage, children’s play becomes increasingly complex, with children spontaneously engaging in role plays, as they construct and act upon imaginative situations based on their own experiences and stories they have heard. Thus, in Waldorf schools, ample time is given for free imaginative play as a cornerstone of children’s early learning.

The environment should protect children from negative influences and the curriculum should include exploring nature through gardening, but also developing practical skills, such as cooking, sewing, cleaning, etc. Relationships are important so groupings last for several years, by way of looping.

3.8 Reggio Emilia Approach (Loris Malaguzzi)

It places emphasis on children’s symbolic languages in the context of a project-oriented curriculum. Learning is viewed as a journey and education as building relationships with people (both children and adults) and creating connections between ideas and the environment.

Through this approach, adults help children understand the meaning of their experience more completely through documentation of children’s work, observations, and continuous educator-child dialogue. The Reggio approach guides children’s ideas with provocations—not predetermined curricula. There is collaboration on many levels: parent participation, educator discussions, and community.

Within the Reggio Emilia schools, great attention is given to the look and feel of the classroom. The environment is considered the “third teacher.” Educators carefully organize space for small and large group projects and small intimate spaces for one, two, or three children. Documentation of children’s work, plants, and collections that children have made from former outings are displayed both at the children’s and adults’ eye level. Common space available to all children in the school includes dramatic play areas and worktables.

There is a center for a gathering called the atelier (art studio) where children and children from different classrooms can come together. The intent of the atelier in these schools is to provide children with the opportunity to explore and connect with a variety of media and materials. The studios are designed to give children time, information, inspiration, and materials so that they can effectively express their understanding through the “inborn inheritance of our universal language, the language that speaks with the sounds of the lips and of the heart, the children’s learning with their actions, their signs, and their eyes: those “hundred languages” that we know to be universal. There is an atelierista (artist) to support this process and instruct children in arts.

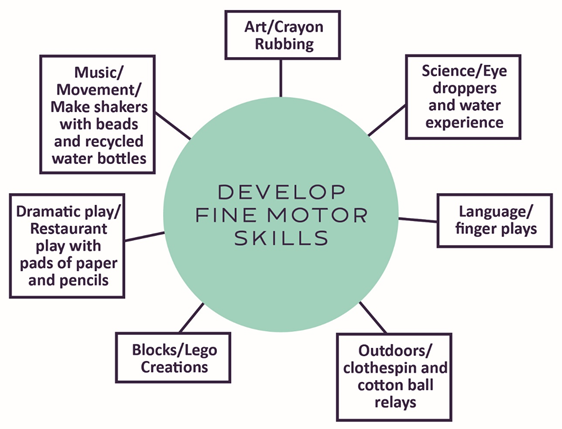

3.9 Webbing

The Reggio Emilia Approach is an emergent curriculum. One method that many Early Childhood Educators use when planning emergent curriculum is curriculum webbing based on observed skills or interests. This method uses brainstorming to create ideas and connections from children’s interests to enhance developmental skills. Webbing can look like a “Spider’s Web,” or it can be organized in list format

Webbing can be completed by:

- An individual educator

- A team of educators

- Educator and Children

- Educators, Children, and Families

Webbing provides endless planning opportunities as extensions continue from observing the activities and following the skills and interests exhibited. As an example demonstrates a web can begin from a skill to develop, but it can also be used in a Theme/Unit Approach such as transportation; friendships; animals, nature, etc.

3.10 Project Approach

The project approach is an in-depth exploration of a topic that may be child-or educator-initiated and involve an individual, a group of children, or the whole class. A project may be short-term or long-term depending on the level of children’s interests. What differentiates the project approach from an inquiry one is that within the project approach, there is an emphasis on the creation of a specific outcome that might take the form of a spoken report, a multimedia presentation, a poster, a demonstration, or a display. The project approach provides opportunities for children to take agency of their own learning and represent this learning through the construction of personally meaningful artifacts. If utilized effectively, possible characteristics may include active, agentic, collaborative, explicit, learner-focused, responsive, scaffolded, playful, language-rich, and dialogic.

In the project approach, adults and children investigate topics of discovery using six steps: Observation, Planning, Research, Exploration, Documentation, and Evaluation.

- Observation: An educator observes children engaging with each other or with materials and highlights ideas from the observations to further explore.

- Planning: Educators talk with children about the observation and brainstorm ideas about the topic and what to explore

- Research: Educators find resources related to the topic

- Explore: Children engage with experiences set around the topic to create hypotheses, make predictions, and formulate questions

- Documentation: Educators write notes, and create charts and children draw observations and fill in charts as they explore topics/questions

- Evaluate: Educators and children can reflect on the hypotheses originally developed and compare their experiences to predictions. Evaluation is key in determining skills enhanced and what worked or what did not work and why.

The benefits of a project approach are that young learners are directly involved in making decisions about the topic focus and research questions, the processes of investigation, and the selection of the culminating activities. When young learners take an active role in decision-making, agency, and engagement is promoted.

3.11 Culturally Appropriate Approach

The Cultural Appropriate Approach has evolved over the years and the practice of valuing children’s culture is imperative for children to feel a sense of belonging in ECE (Early Childhood Education) programs. Sensitivity to the variety of cultures within a community can create a welcoming atmosphere and teach children about differences and similarities among their peers. Consider meeting with families prior to starting the program to share cultural beliefs, languages, and or traditions.

Classroom areas can reflect the cultures in many ways:

- Library Area: Select books that represent cultures in the classroom

- Dramatic Area: Ask families to donate empty boxes of foods they commonly use, bring costumes or clothes representative of the culture

- Language: In writing center include a variety of language dictionaries

- Science: Encourage families to come and share a traditional meal

Pause to Reflect

Should children be given the opportunity to engage with Indigenous toys or crafts without understanding their connection to a specific nation?

What is the responsibility of the educator in this situation?

How can families play a role in sharing?

Important Things to Remember

- Play is how children make sense of the world and is an effective method of learning for young children. Ideas and skills become meaningful; tools for learning are practiced; and concepts are understood.

- Play engages children’s attention when it offers a challenge that is within the child’s capacity to master.

- Research has proven that children learn best in environments that enable them to be fully involved in meaningful exploration, spontaneous play, and inquiry.

- Supportive early learning environments enable children to communicate and express themselves in a wide variety of forms: verbally, non-verbally, and through creative expression.

- Areas of development are integrated, and children learn many concepts and skills at the same time.

- Developmentally appropriate practices are age-appropriate, individually appropriate, and socio-culturally appropriate.

Supplemental Readings

References

Berk, L. & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding Children’s Learning: Vygotsky and Early Childhood Education. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of the Young Child.

Excerpts from ELECT Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014

Gordon, A. M. & Browne, K. W. (2001) Beginnings and Beyond, 8th edition. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Greenspan, S. & Shanker, S. (2004). The First Idea: How Symbols, Language and Intelligence Evolved from Our Primate Ancestors to Modern Humans. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain

How Does Learning Happen? Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014

Kagan, S. & Britto, P. (2005). Going Global with Indicators of Child Development. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Final Report. New York, NY: UNICEF.

Kagan, S. L. & Lowenstein, A. E. (2004). School readiness and children’s play: Contemporary oxymoron or compatible option? In E.F. Zigler, D.G. Singer & S.J. Bishop-Josef (Eds.), Children’s Play: The Roots of Reading. Washington, DC: Zero To Three Press, 59-76.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009) Developmentally Appropriate NAEYC. Practice in Early Childhood

Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally- shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/PSDAP.pdf

The Creative Curriculum for Preschool, Fourth Edition by the U.S. Department of Education is in the public domain