7 Using Old Photographs to Gain New Perspectives on Refugees, Past and Present

Sonya de Laat

In the summer of 2018 an unprecedented number of people claiming to be refugees crossed into Canada at unofficial border points. Many Canadians learned of these events through photographs and other visual media circulating through the press. Responding to such images, public reaction in Canada has been mixed. While some people support actions aimed at helping these families and individuals, others have sensationalized the situation by labelling it a “crisis” and calling border-crossers “illegals” or “queue jumpers.”

It is not the photographs on their own that have contributed to this ambivalence, since “photographs are mute”. Photographs take their meaning from the words around them: captions, news anchor statements, accompanying articles, or even the “narrative templates in our own minds.”1 Responses such as those that surfaced this summer are not new. Indeed, they are reflective of a historical pattern of response towards refugees over the past century. Looking at one set of photographs from that era can give us another perspective on current debates and remind us of the powerful role photography plays in mediating social relations.

There is a little-known collection of photographs made by Lewis Hine for the American Red Cross (ARC) at the tail end and immediately following the Great War. The ARC hired Hine because of his reputation as America’s foremost photographer of social reform issues. Hine had trained as a sociologist and an educator. He was not a journalist, but rather a social reformer whose main medium of advocacy was the camera. By the mid-1910s, Hine had developed a reputation as “the most extensive and successful photographer of social welfare work in [America].”2 During the First World War, his positive portrayals of refugees served the ARC well in their development as America’s foremost relief agency .

This dive into the ARC and Lewis Hine archives is meant to contribute to reflections on new directions for humanitarian photography that take into consideration historical legacies of particular practices around the use of photography, and to reflect on the role of photography in influencing or changing peoples’ perceptions. It’s in this sense that Hine’s photographs give insight into the cycles of rising and falling sympathy towards refugees that have occurred over the past century and the role of the mobilization of photography therein.

A group of people “that appeared in the public arena virtually overnight,”3 the term “refugee” was resurrected during the Great War’s early years, expanding from its original meaning of religious persecution to encompass all people fleeing persecution and seeking safety. Representing them as “hapless wartime victims”, Hine’s photographs allowed Europe’s refugees to stake a claim on American sentiments, however briefly. Indeed, the ARC’s sympathetic portrayal of refugees during the height of the war had already, by 1918, become a counter-narrative to debate and anxiety about refugees.

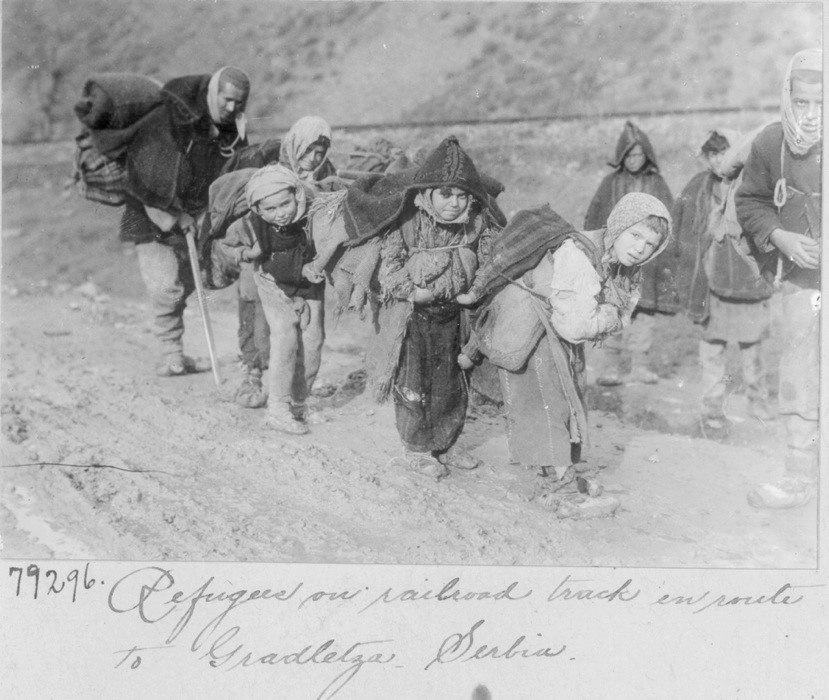

After the war, Hine continued to photograph refugees for the ARC’s Special Survey of reconstruction needs. His pictures and captions in many ways defined and specified the condition of being a refugee, or “refugeedom.”4 The content and themes in Hine’s refugee-labeled photographs contain elements that are repeated in pictures of refugees today. He frequently pictured family groups, with children, burdened under the weight of their worldly possessions, as they travelled cross-country by foot along dusty or muddy roadways, or along the rail lines (see Image 1).

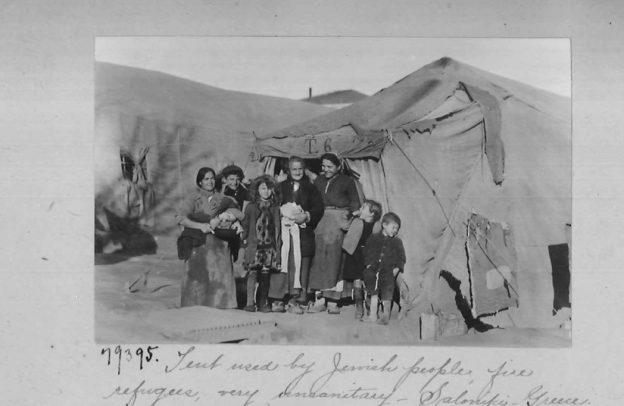

Perseverance, ingenuity, capacity to labour, and drive despite loss were all themes Hine built into his images, and they were themes an American audience could relate to. All the while he deliberately focused on expressions of hope, or at least positive qualities of resilience and resourcefulness (see Image 2). I interpret what Hine was doing as working along the lines of philosopher Richard Rorty’s concept of “sentimental education,” where narratives (in the captions) and representations (in the pictures) have the potential “to expand the reference of terms ‘our kind of people’ and ‘people like us’” to include people who might otherwise be considered ‘other’ or ‘them’.5

Despite all this, in the early months of post-war peace, refugees—foundational to ARC reputation and practice—were being outmaneuvered by a narrowing of humanitarian idealism as the wartime sense of international humanitarianism as a patriotic duty was being replaced by an insular nationalistic fervor. The visual framing and displacement of refugees from the ARC’s publications forms part of an ongoing pattern of the rise and fall of sentiments towards refugees that would continue through the century to today.

Visual culture scholars will often base much of their analysis on the ways in which photographs have been used or the conditions in which pictures develop; what Elizabeth Edwards has termed their “social life”.6 But Hine’s Special Survey pictures have almost no “social life” to speak of. Of the approximately 1000 photographs he made in Italy, Serbia, Greece, and Belgium between November 1918 and April 1919, the ARC would publish fewer than a handful.

That’s why I propose instead to build on Ariella Azoulay’s idea of “watching” his photographs to reconstruct what little social life they had.7 Instead of simply looking at photographs, watching a picture is fundamentally an act of historical thinking. “Watching” entails dimensions of time and movement that need to be re-inscribed in the interpretation of the still photographic image. This action, according to Azoulay, is an intentional act of viewing of the photograph that “reconstructs the photographic situation and allows a reading of the injury [or I would say, affect or condition] inflicted on others [as] a civic skill, not an exercise in aesthetic appreciation”. “Watching” the photographs in Azoulay’s sense can return to us clues as to Hine’s intentions and perspectives; it also enables a richer glimpse into refugeedom.

Approaching photographs in the manner I propose is essential to foster a deeper understanding of the condition and experience of being a refugee. In particular, I embrace John Berger’s idea that “a radial system has to be constructed around the photograph so that it may be seen in terms which are simultaneously personal, political, economic, dramatic, everyday and historic”.8 Here, I’m demonstrating the way photographs “continue to exist in time, instead of being arrested moments” by building a “radial system” that explores the historical and social context of the arena of actors, actions that existed and continue to exist beyond the picture’s frame as photography plays an ever greater role in mediating perceptions.

“Watching”—rather than looking—at photographs, also unravels what Azoulay has termed “potential histories,” which opens the mind to trajectories that might have happened had mechanisms of control been different or nonexistent. Exploring potential histories is an act of challenging official memory and dominant histories that obscure or deny spectators’ ability to judge situations from multiple perspectives, let alone recognize their being implicated (or even complicit) in them.

Historical thinking and exploring the potential histories in archival photographs can lead to questioning such as:

- What discursive and imaginary opportunities emerge when comparing historical and contemporary photographs of refugeedom? What happens to the discourse once that civil space is opened up?

- What might have happened had the ARC published a large photo-spread of post-war refugee and reconstruction needs, from that Special Survey, and framed them as needs that Americans were ideally positioned to respond to? How might that have impacted political policies such as the 1924 Johnson-Reid Act which emerged in response to First World War refugees seeking settlement in North America?

- Given that Hine ascribed the term “refugee” in his captions to only certain types of people, while calling others “beggars” or “nomads”, what might this reveal in terms of histories of limits to humanitarian imagination or the politics of naming today?

- How might reflection on the pattern of visual depictions of refugees—the visual culture of refugeedom—over the past century impact considerations of moral responsibilities and social obligations forged before or that extend beyond nationalism, or the increasing social constructions of sedentary bias or nativism in policy changes over the past century?

I’m not sure yet what such a new humanitarian/historical photography might look like, where these lines of questioning may lead, but in a moment in which there are approximately 68.5 million forcibly displaced people, of which some 25.4 million are refugees according to the UNHCR definition, historical perspective can open to new lines of inquiry or different ways of seeing the situation (in the words of John Berger).9 I look forward to seeing the possibilities that unfold and what implications on public discourse about refugees it may have.