4 Not so Accidental: Farmworkers, Car Crashes, and Capitalist Agriculture

Edward Dunsworth

Early in August 2018, near the southern Italian city of Foggia, sixteen migrant farmworkers from various African countries were killed in two separate car accidents. In both cases, vans taking migrants back to camp after work collided with trucks carrying tomatoes from the very fields where they had spent the day toiling. The tragedy brought international media scrutiny to the Puglia region’s agricultural sector, where African migrants are housed in squalid camps and ferried from farm to farm by mob-connected recruiters to work dangerous jobs for minimal pay and with few protections. It also sparked resistance from farmworkers themselves, who on 8 August took the roads of the tomato district, chanting “we are not slaves, no to exploitation.”

This horrific loss of life came, unfortunately, as little surprise to activists and academics working on farm labour, both in Italy and around the world. In Canada, it called up memories of the 2012 crash in Hampstead, Ontario, when a van taking Latin American poultry farm workers home collided with a transport truck, killing ten farmworkers and the truck driver and leaving just three survivors. For me, it also brought to mind the countless times during my research on tobacco labour in twentieth-century Ontario that I’ve come across reports of tobacco workers dying on the road while looking for work or heading into town after the workday.

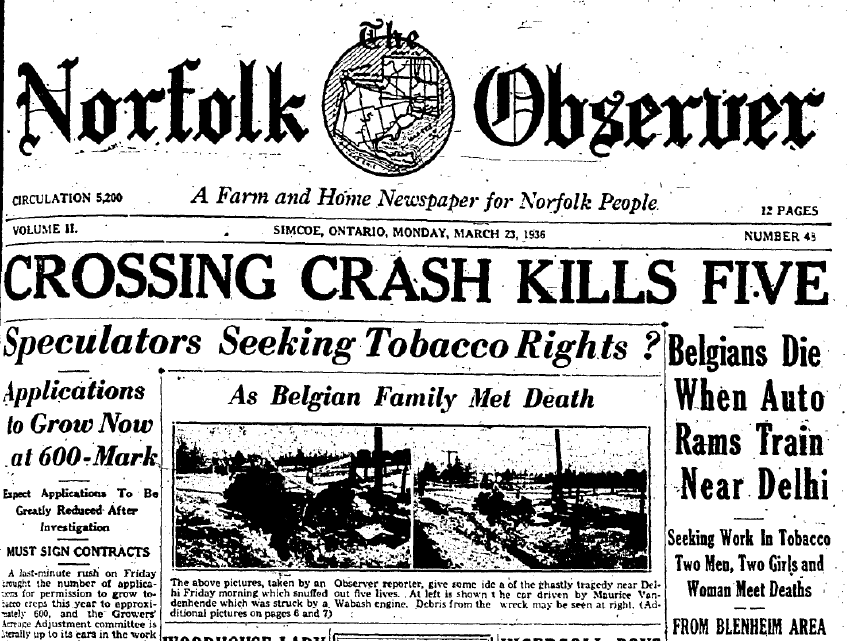

In 1936, for example, the Verheecks, a Belgian immigrant family of four living in Blenheim, Ontario, received a tip that work was available for them on a tobacco farm 150 kilometers down the highway in Delhi. Under the economic pressures of the Great Depression, that was enough to get them on the road, and the four of them – mother Sidonia, father Acheele, and daughters Georgette and Marlette, aged 17 and 12 – set out the next day along with a family friend, Maurice Vandenhende. Just outside of Delhi, however, their car failed to brake at a rail crossing and was struck by an oncoming train, killing all five.1

In the media and in the evaluations of police and other state officials, crashes such as these are usually labelled as “accidents,” though not blameless ones. Forensic investigators attempt to determine exactly what happened leading up to and at the exact moment of the collision, in large part with a view to ascribing culpability. Did someone run a stop sign? Were all drivers properly licensed? Stepping back a bit from the scene of the crash and adopting a broader perspective on the propensity of farmworkers to be involved in car crashes, it quickly becomes apparent that categories like “accident” and “individual responsibility” are woefully inadequate for explaining the all-too-common occurrence of tragedies like those in Foggia, Hampstead, and Delhi.

Instead, it is more accurate to understand dying by vehicular collision as an occupational hazard of capitalist agriculture. While capitalist agriculture – at least in unmechanized crops – is known for being labour-intensive, it is also what we might call land-extensive. Over the last hundred-plus years, downward pressures on commodity prices have encouraged producers to grow food on ever-greater scales in order minimize the per-unit cost of production. They have also tended to specialize: while mixed-crop farms still exist, more and more common are vast fields of a single crop, also known as mono-cropping.

This lay-out of land and crops has advantages for producing at scale but poses a challenge to employers when it comes to labour. Most agricultural commodities require a surge of workers for only short periods of time – most obviously during harvests. Thus, a persistent feature of capitalist agriculture has been the circulation of labour across vast expanses of space, as workers travel to the places that require their labour power. This need for mobile labour has engendered numerous techniques for supplying it–from private recruiters to state-managed guestworker programs–dating back well over a century.2 Historian Gunther Peck has written brilliantly on the ways in which turn-of-the-twentieth-century padrones “commodified” mobility and space in building large commercial empires based on labour supply throughout the North American west.

Even after farmworkers arrive in the distant places where their labour is needed, travel across large distances remains an important feature of their life and work. As farm sizes grow, it is not uncommon for farmers to own or rent multiple fields distributed across large areas. In my own experience working alongside Mexican migrants on farms in southwestern Ontario, the farthest field we travelled to was a 45-minute drive from the home farm and bunkhouse. The farmer had it timed so that we would depart exactly 45 minutes before sunrise, driving through the dark in order to arrive right as the sun’s first light streamed across the field, allowing for maximum production during the daylight hours. Some days we would work until dark before returning to the bunkhouse. Workers often took advantage of the long drives to sneak in a few more minutes of sleep, sometimes leaving the driver as the only person awake in the van. Fortunately, he was not shy about blasting norteña music to keep himself awake, napping coworkers be damned.

Farms are also, of course, usually located at some distance from the nearest shop or town, meaning that workers wanting to run an errand after work often need to travel by bicycle or foot, along poorly lit rural roads with no sidewalks, a situation that has been insightfully described by geographer Emily Reid-Musson.

Taken together, these aspects of capitalist agriculture ensure that farmworkers spend a surprising amount of time in transit, in cars or vans, or on bicycle or foot. As Frank Bardacke writes in the prologue to his history of the United Farm Workers, cars are “perhaps the most essential agricultural implements in California.” And time on the road, especially with fatigued drivers, the conditions of rural roadways, and an absence of regulation around work-related travel, brings a greater likelihood of “accidents,” a fact that I’ve been repeatedly reminded of during my research. To give just one more example, in 1942, a First Nations tobacco worker named Alex Porter (likely from Munsee-Delaware nation) was changing a flat tire on his car, just east of Tillsonburg when he was struck by a passing vehicle that did not remain on the scene. Porter was listed as being in “critical condition” and it is not clear what became of him.3

The two examples from my research (out of dozens) make it clear that while the methods of labour supply have changed over time, capitalist agriculture’s requirement of mobile workers moving across vast spaces – and the dangers inherent in this set-up – have remained constant. Also stubbornly persistent has been the inability for most observers and authorities to get beyond the “accident” paradigm and consider the structural reasons why such incidents continue to happen or what might be done to curtail them.

In Italy, in the wake of the horrific deaths of sixteen men, there are some glimmers of hope. The Puglia region has committed to implementing a public transit system to safely transport farm workers during the harvest season, something that unions and farm labour activists have been advocating for years. In Canada, despite calls from activists for an inquest into the Hampstead crash, Ontario’s chief coroner ultimately declined, determining that the collision was a result of “driver error,” and that an inquest was not likely to produce recommendations that would prevent similar incidents in the future. An examination of the history of automobile accidents and farmworkers reveals that such incidents are not isolated tragedies, but part and parcel of capitalist agriculture, a structural problem that requires structural solutions.