10 Little Bear’s Cree and Canada’s Uncomfortable History of Refugee Creation

Benjamin Hoy

Refugees create complicated political and social climates. Federal decisions to admit or reject individuals, families, and communities fleeing from hardships intertwine humanitarian concerns, political profiteering, immigration policy, domestic security, and racial perceptions into an often-ugly mess. Refugees force countries to consider their moral obligations to those less fortunate and to examine the possibility of their own complicity in the international crisis that sparked movement. As Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi’s September 2015 comments regarding the Syrian refugee crisis suggest, Canada’s treatment of refugees is a matter of national pride and identity.1 A country’s failure to live up to domestic and international expectations opens it up to disdain and derision at home and abroad.

Although much of the recent media frenzy surrounding immigration and refugees has focused on Canada’s obligation to reacquire or defend its reputation as a sanctuary for those fleeing violence, Canada’s historical relationship to movement under stress is quite a bit more complicated. There is no simple binary between countries that produce refugees, and those that care for them. Most countries, considered historically, are involved on both sides of the equation. The exodus of the Cree after the 1885 Rebellion offers a Canadian example. The Cree’s experience serves not only as a reminder of our uncomfortable past, but also reveals some of the limitations in the model we continue to use to conceive of refugees and our obligations to them.

By the 1870s, the decline in buffalo across the Canadian and American plains had created a crisis of subsistence for groups such as the Cree. Indigenous hunters moved back and forth across the border hoping to take advantage of the few remaining herds they could find. The situation grew worse as time passed. The American military began evicting “Canadian” Indigenous peoples found hunting south of the border.

The practical realities of life along the border made such actions difficult. Canada and the United States had surveyed their shared border along the plains less than a decade earlier (largely between 1872 and 1874) and the social, economic, and political connections people maintained reflected the newness of the division. The Cree, Lakota, Dakota, and Métis maintained extensive transnational connections and hunting parties continued to cross the border with ease.

Canada’s refusal to supply the rations and annuities it had promised to the Cree through treaties exacerbated the disappearance of the buffalo and led to widespread suffering, starvation, and resentment, despite the long distances hunting parties trekked. Canada’s failure to honor its treaty promises reflected both an ineffectual and insufficient administration in the West as well as an intentional assimilationist policy. Canadian and American Indian agents withheld rations from individuals or groups who tried to live beyond the confines of their reservations, making starvation a powerful tool that Canada and the United States utilized to exert social, political, and cultural control.

Conditions for the Cree living near the border became grim by 1883. The Cree failed to find enough buffalo to support themselves and crop failures eliminated other sources of subsistence. The Cree were not alone. During the winter of 1882-1883, an estimated one-sixth to one-quarter of the Piegan population in Montana died of starvation. Desperate to avoid a similar fate, the Cree sent raiders against other Indigenous groups in an attempt to secure much needed horses and supplies. On both sides of the border, the Cree found themselves in dire straits.

The Northwest Rebellion of 1885, over prolonged disagreements between the Métis and the Canadian government, exacerbated an already difficult situation. During the rebellion, several members of Big Bear’s Band of Cree killed nine settlers at Frog Lake and took others hostage. Although the Cree did not intend these attacks to be part of the rebellion, the Canadian government understood them as such. Canadian authorities captured Big Bear on July 2, 1885, and sentenced him to three years in prison, despite his attempt to prevent the violence. Imasees (Little Bear) and other Cree leaders including Lucky Man and Little Poplar remained free but feared similar reprisals.

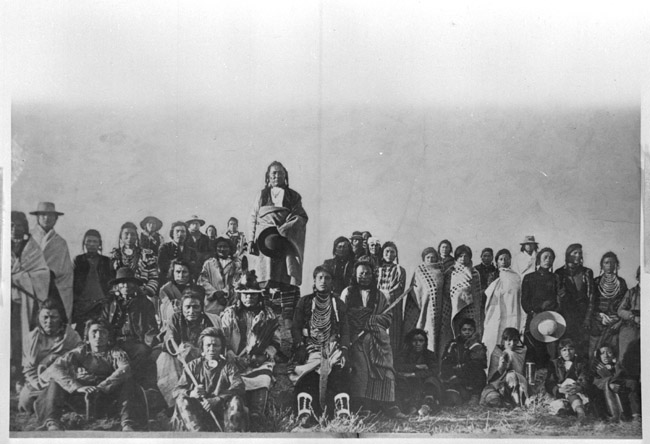

In the aftermath of the 1885 Rebellion, Little Bear and Little Poplar led hundreds of their followers to the United States hoping to avoid arrest or persecution. The four hundred-mile journey, conducted without adequate provisions or horses, created great hardship. The American government labeled the Cree as undesirable refugees upon their arrival and did little to provide them with assistance.

The categorization of the Cree as refugees condensed a complicated situation into a simple mould. The term refugee was correct in the sense that the Cree had left their homes and crossed national lines out of fear that if they stayed they would be subjected to violence, arrest, or persecution. The Cree did not, however, flee to wholly foreign lands. Indigenous boundaries did not coincide with European ones, making it difficult to apply European understandings of a ‘refugee,’ which relied on the boundaries of nation states, to a transnational people.

The United States’ interpretation of Little Bear’s band as refugees glossed over a complicated situation, but it allowed the American government to achieve two significant aims. First, the refugee status allowed the United States to distance itself from any legal or treaty responsibility it might have to the Cree, despite the historic connections Little Bear and others maintained on both sides of the border. In short, their refugee status allowed the United States to blame the Cree’s predicament solely on the Canadian government. The American government provided the Cree refugees with rations, but did so as a matter of voluntary charity and as a peace-keeping effort. It admitted no legal compulsion to do so. Second, the Cree’s refugee status also allowed the United States to chastise Canada for its unenlightened Indian policy, a satisfying position given Canada’s indictment of American Indian policy following Sitting Bull’s exodus from the United States after the battle of Little Big Horn, and the Nez Perce’s attempted flight in 1877.

Although the American government’s classification of the Cree as refugees allowed it to achieve a number of significant aims, it did little to improve the Cree’s situation. Little Bear failed to convince the United States to recognize the Cree’s claim to land south of the border. John Dewitt Clinton Atkins, commissioner of Indian Affairs in the United States, argued that the poor treatment of the Cree sullied the dignity of the American government, but his pleas resulted in few practical changes. American newspapers described the “Canadian” Cree as thieving scavengers and little was done to offer them a permanent home south of the border. As public opinion of the Cree worsened, their status as refugees from Canada opened up calls for their expulsion.

In 1895, the United States Congress appropriated $5,000 to rid the country of the “Canadian” Cree, arguing that they violated American gaming law and had become a general nuance. Congress believed that Canada alone should be responsible for rectifying this difficult situation. During the summer of 1896 the American military deported Little Bear, Lucky Man (Papewes) and 523 Indigenous peoples, believed to be Canadian Cree, by force to Canada. While the American military promised that the Canadian government had granted the Cree amnesty, Northwest Mounted Police officers arrested Lucky Man and Little Bear as soon as the American military delivered them across the border. The Canadian government later dropped the charges against the two men, but the arrests confirmed longstanding fears of persecution by the Canadian state.

By the turn of the century, most of the Cree who had followed Lucky Man and Little Bear returned to Montana despite the hardships they had faced there. Over the next two decades, Little Bear continued to push for land. In 1916, almost thirty years after the rebellion had driven him from his home, Little Bear found a permanent home for his people on the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana.

The case of Little Bear reveals the challenges that a tight adherence to legal status can have in regions filled with motion and complexity. It highlights the ways that countries can distance themselves from political and legal responsibility by declaring a people as refugees instead of accepting some measure of culpability in their condition.

Moreover, it suggests that we must look beyond the admissions statistics themselves to inquire as to the long-term quality of living being provided to those fleeing violence. Although Canadian political leaders have recently publicized the number of refugees they would admit to Canada if they were elected to office, admission serves as only one component of refugee support. Little Bear and hundreds of Cree, for example, had no difficulty entering into the United States and even a forcible deportation did not keep them out of Montana. For them, the difficulties occurred not in crossing the border but in securing land recognition and meaningful employment once there. Allowing refugees to fester in limbo for years, or for decades in the case of Little Bear, skirts responsibility, increases suffering, and encourages risk taking by those seeking refuge. Finally, Little Bear’s case provides a cautious reminder that Canada, like many other countries, has not only accepted refugees, but also created them.