4.1 Basic Structure and Function of the Nervous System

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the anatomical and functional divisions of the nervous system

- List the basic functions of the nervous system

The picture you have in your mind of the nervous system probably includes the brain, the nervous tissue contained within the cranium, and the spinal cord, the extension of nervous tissue within the vertebral column. That suggests it is made of two organs—and you may not even think of the spinal cord as an organ—but the nervous system is a very complex structure. Within the brain, many different and separate regions are responsible for many different and separate functions. It is as if the nervous system is composed of many organs that all look similar and can only be differentiated using tools such as the microscope or electrophysiology. In comparison, it is easy to see that the stomach is different than the esophagus or the liver, so you can imagine the digestive system as a collection of specific organs.

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

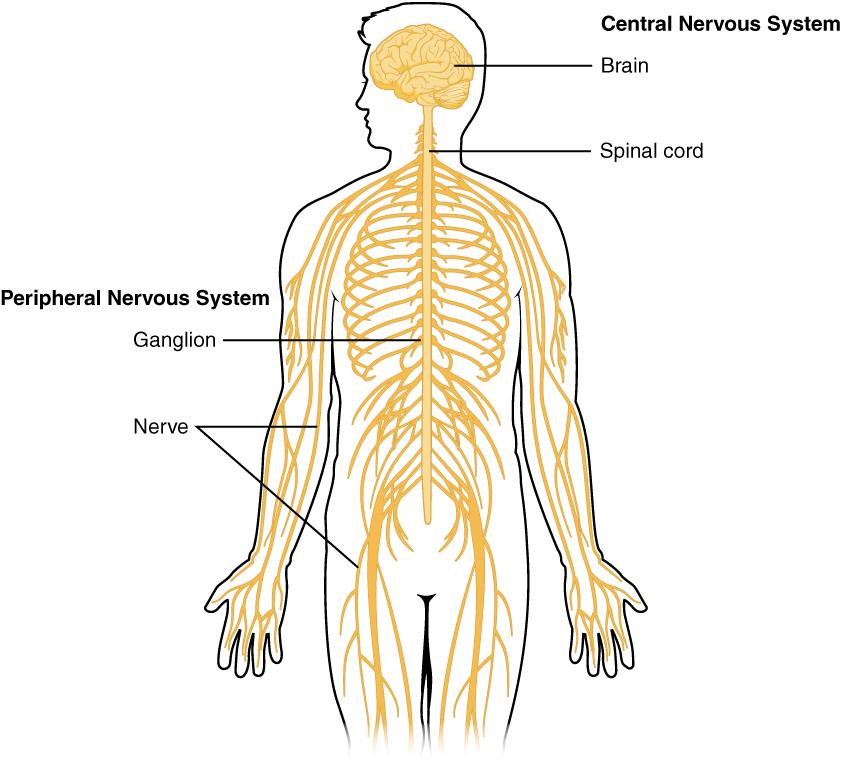

The nervous system can be divided into two major regions: the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) is the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is everything else (Figure 4.2). The brain is contained within the cranial cavity of the skull, and the spinal cord is contained within the vertebral cavity of the vertebral column. It is a bit of an oversimplification to say that the CNS is what is inside these two cavities and the peripheral nervous system is outside of them, but that is one way to start to think about it. In actuality, there are some elements of the peripheral nervous system that are within the cranial or vertebral cavities. The peripheral nervous system is so named because it is on the periphery—meaning beyond the brain and spinal cord. Depending on different aspects of the nervous system, the dividing line between central and peripheral is not necessarily universal.

Components of the Central Nervous System

The brain and the spinal cord are the central nervous system, and they represent the main organs of the nervous system. The spinal cord is a single structure, whereas the adult brain is described in terms of four major regions: the cerebrum, the diencephalon, the brain stem, and the cerebellum. A person’s conscious experiences are based on neural activity in the brain.

The Cerebrum

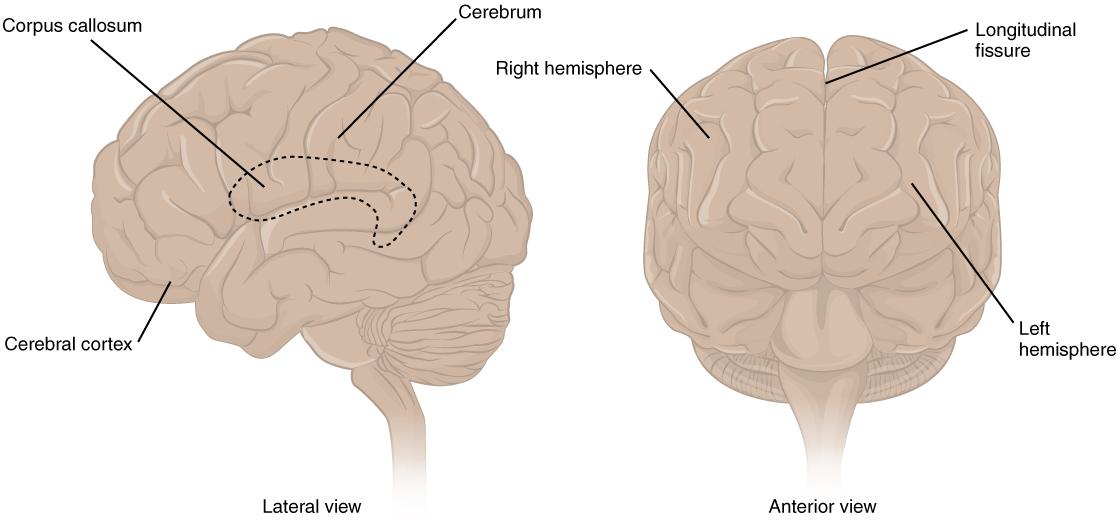

The iconic gray mantle of the human brain, which appears to make up most of the mass of the brain, is the cerebrum (Figure 4.3). The wrinkled portion is the cerebral cortex, and the rest of the structure is beneath that outer covering. There is a large separation between the two sides of the cerebrum called the longitudinal fissure. It separates the cerebrum into two distinct halves, a right and left cerebral hemisphere.

Many of the higher neurological functions, such as memory, emotion, and consciousness, are the result of cerebral function. The complexity of the cerebrum is different across vertebrate species. The complexity of the cerebrum separates human thinking from other mammals. The cerebrum can be divided into different regions, each with its own particular function.

The Diencephalon

The diencephalon is the one region of the adult brain that retains its name from embryologic development. The etymology of the word diencephalon translates to “through brain.” It is the connection between the cerebrum and the rest of the nervous system, with one exception. The rest of the brain, the spinal cord, and the PNS all send information to the cerebrum through the diencephalon. Output from the cerebrum passes through the diencephalon.

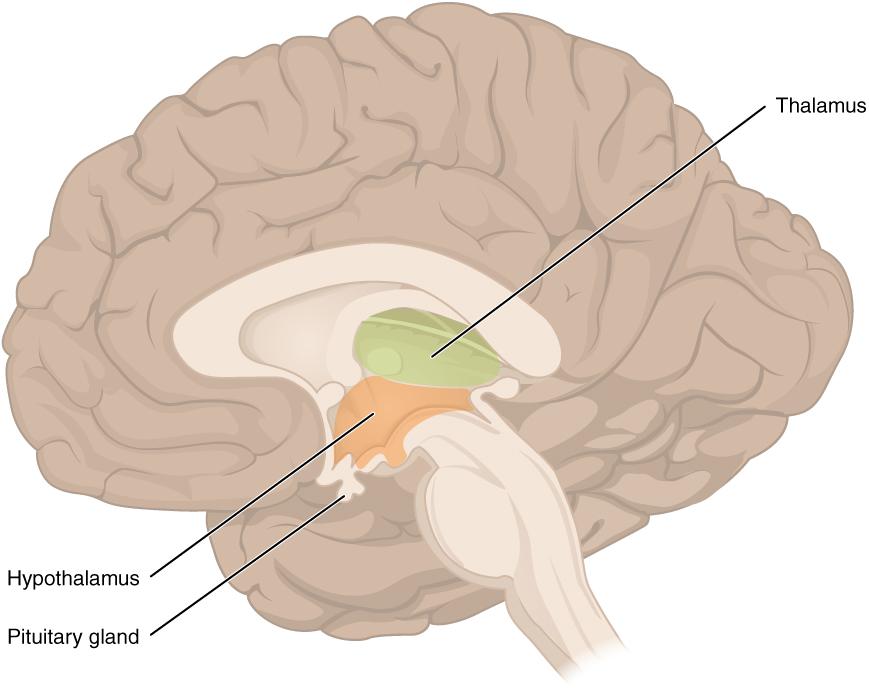

The diencephalon is deep beneath the cerebrum. The diencephalon can be described as any region of the brain with “thalamus” in its name. The two major regions of the diencephalon are the thalamus itself and the hypothalamus (Figure 4.4).

Thalamus: The thalamus is a collection of nuclei that relay information between the cerebral cortex and the periphery, spinal cord, or brain stem. All sensory information, except for the sense of smell, passes through the thalamus before processing by the cortex.

The cerebrum also sends information down to the thalamus, which usually communicates motor commands.

Hypothalamus: Inferior and slightly anterior to the thalamus is the hypothalamus, the other major region of the diencephalon. The hypothalamus is a collection of nuclei that are largely involved in regulating homeostasis. The hypothalamus is the executive region in charge of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system.

Brain Stem

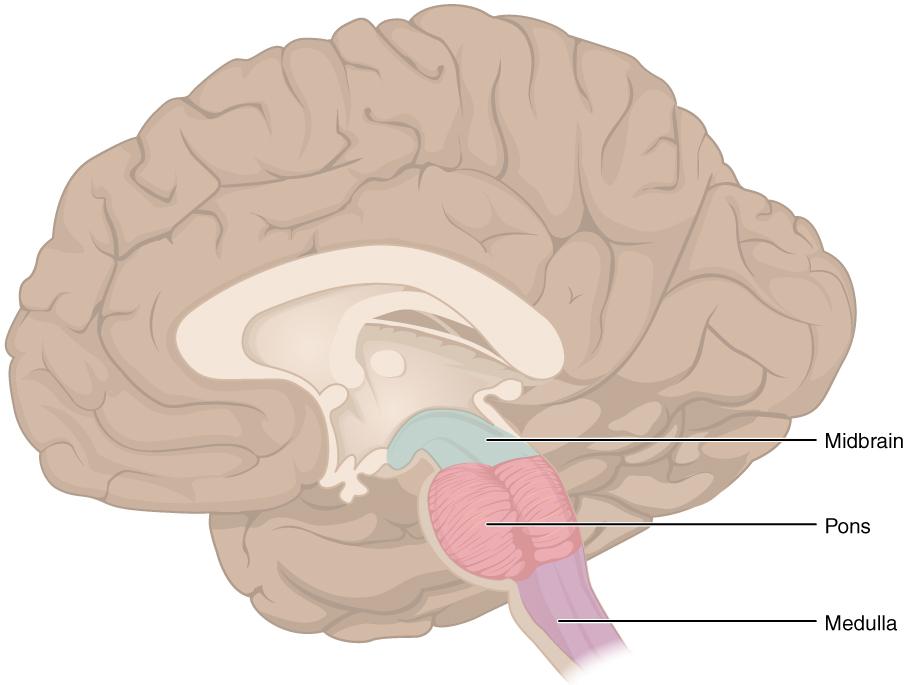

The midbrain, pons and medulla are collectively referred to as the brain stem (Figure 4.5). The structure emerges from the ventral surface of the cerebrum as a tapering cone that connects the brain to the spinal cord. The brainstem coordinates sensory representations of the visual, auditory, and somatosensory perceptual spaces. It also regulates several crucial functions, including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and rates.

The Cerebellum

The cerebellum, as the name suggests, is the “little brain”, and looks like a miniature version of the cerebrum. The cerebellum is largely responsible for coordination of voluntary movement, balance, and posture. It does this by comparing information from the cerebrum with sensory feedback from the periphery through the spinal cord.

The Spinal Cord

The description of the CNS is concentrated on the structures of the brain, but the spinal cord is another major organ of the system.

The length of the spinal cord is divided into regions that correspond to the regions of the vertebral column. The name of a spinal cord region corresponds to the level at which spinal nerves pass through the intervertebral foramina. Immediately adjacent to the brain stem is the cervical region, followed by the thoracic, then the lumbar, and finally the sacral region. The spinal cord is not the full length of the vertebral column because the spinal cord does not grow significantly longer after the first or second year, but the skeleton continues to grow. The nerves that emerge from the spinal cord pass through the intervertebral foramina at the respective levels. As the vertebral column grows, these nerves grow with it and result in a long bundle of nerves that resembles a horse’s tail and is named the cauda equina. The sacral spinal cord is at the level of the upper lumbar vertebral bones. The spinal nerves extend from their various levels to the proper level of the vertebral column.

The spinal cord can be thought of as a “highway” that carries information between the brain and body. Similar to a highway, this information flows in two directions. The ascending tracts of the spinal cord carry sensory information from the body up to the brain. The descending tracts of the spinal cord carry motor commands from the brain out to the body.

Functional Divisions of the Nervous System

The nervous system can also be divided on the basis of its functions. There are two ways to consider how the nervous system is divided functionally. First, the nervous system can be divided based on control of the body – it can be somatic or autonomic. Secondly, the nervous system can be divided based on its basic functions – sensation, integration and response.

Controlling the Body

The nervous system can be divided into two parts mostly on the basis of a functional difference in responses. The somatic nervous system (SNS) is responsible for conscious perception and voluntary motor responses. Voluntary motor response means the contraction of skeletal muscle, but those contractions are not always voluntary in the sense that you have to want to perform them. Some somatic motor responses are reflexes, and often happen without a conscious decision to perform them. If your friend jumps out from behind a corner and yells “Boo!” you will be startled and you might scream or leap back. You didn’t decide to do that, and you may not have wanted to give your friend a reason to laugh at your expense, but it is a reflex involving skeletal muscle contractions. Other motor responses become automatic (in other words, unconscious) as a person learns motor skills (referred to as “habit learning” or “procedural memory”).

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for involuntary control of the body, usually for the sake of homeostasis (regulation of the internal environment). Sensory input for autonomic functions can be from sensory structures tuned to external or internal environmental stimuli. The motor output extends to smooth and cardiac muscle as well as glandular tissue. The role of the autonomic system is to regulate the organ systems of the body, which usually means to control homeostasis. Sweat glands, for example, are controlled by the autonomic system. When you are hot, sweating helps cool your body down. That is a homeostatic mechanism. But when you are nervous, you might start sweating also. That is not homeostatic, it is the physiological response to an emotional state.

Basic Functions

The nervous system is involved in receiving information about the environment around us (sensation) and generating responses to that information (motor responses). The nervous system can be divided into regions that are responsible for sensation (sensory functions) and for the response (motor functions). But there is a third function that needs to be included. Sensory input needs to be integrated with other sensations, as well as with memories, emotional state, or learning (cognition). Some regions of the nervous system are termed integration or association areas. The process of integration combines sensory perceptions and higher cognitive functions such as memories, learning, and emotion to produce a response.

Sensation. The first major function of the nervous system is sensation—receiving information about the environment to gain input about what is happening outside the body (or, sometimes, within the body). The sensory functions of the nervous system register the presence of a change from homeostasis or a particular event in the environment, known as a stimulus. The senses we think of most are the “big five”: taste, smell, touch, sight, and hearing. There are actually more senses than just those, but that list represents the major senses. Those five are all senses that receive stimuli from the outside world, and of which there is conscious perception. Additional sensory stimuli might be from the internal environment (inside the body), such as the stretch of an organ wall.

Response. The nervous system produces a response on the basis of the stimuli perceived by sensory structures. An obvious response would be the movement of muscles, such as withdrawing a hand from a hot stove, but there are broader uses of the term. The nervous system can cause the contraction of all three types of muscle tissue. For example, skeletal muscle contracts to move the skeleton, cardiac muscle is influenced as heart rate increases during exercise, and smooth muscle contracts as the digestive system moves food along the digestive tract. Responses also include the neural control of glands in the body as well, such as the production and secretion of sweat to lower body temperature.

Responses can be divided into those that are voluntary or conscious (contraction of skeletal muscle) and those that are involuntary (contraction of smooth muscles, regulation of cardiac muscle, activation of glands). Voluntary responses are governed by the somatic nervous system and involuntary responses are governed by the autonomic nervous system.

Integration. Stimuli that are received by sensory structures are communicated to the nervous system where that information is processed. This is called integration. Stimuli are compared with, or integrated with, other stimuli, memories of previous stimuli, or the state of a person at a particular time. This leads to the specific response that will be generated. Seeing a baseball pitched to a batter will not automatically cause the batter to swing. The trajectory of the ball and its speed will need to be considered. Maybe the count is three balls and one strike, and the batter wants to let this pitch go by in the hope of getting a walk to first base. Or maybe the batter’s team is so far ahead, it would be fun to just swing away.