3.3 Types of Muscle Contractions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain concentric, isotonic, and eccentric contractions

- Describe the length-tension relationship

To move an object, referred to as load, the sarcomeres in the muscle fibers of the skeletal muscle must shorten. The force generated by the contraction of the muscle (or shortening of the sarcomeres) is called muscle tension. However, muscle tension also is generated when the muscle is contracting against a load that does not move, resulting in two main types of skeletal muscle contractions: isotonic contractions and isometric contractions.

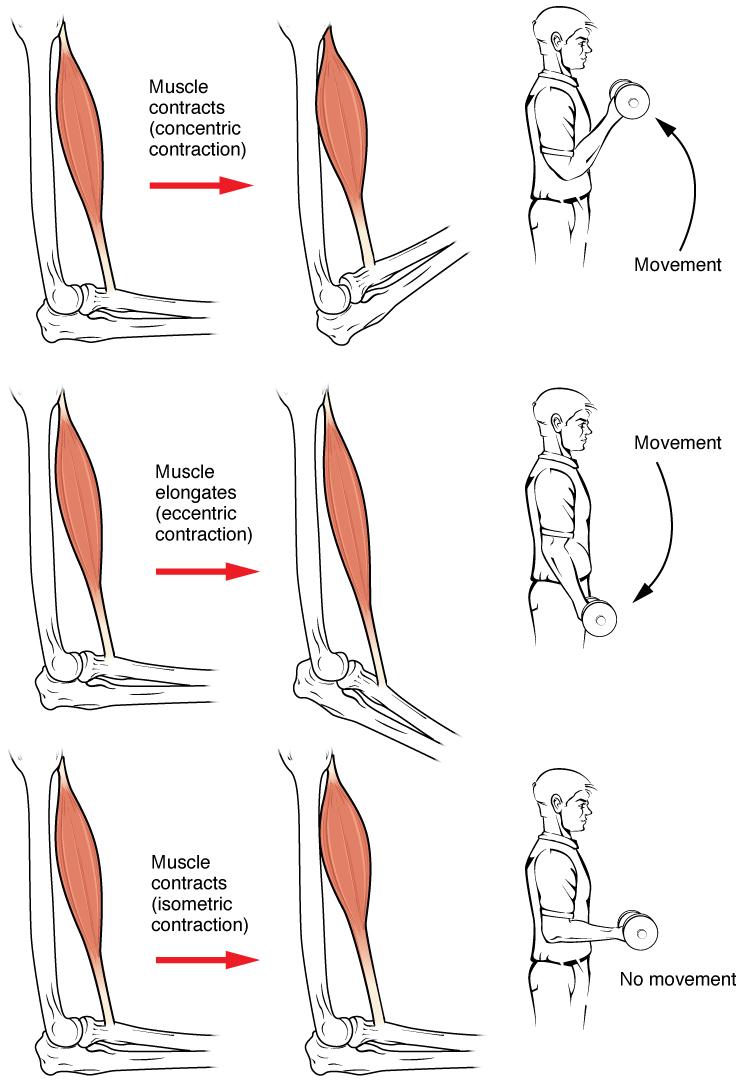

In isotonic contractions, where the tension in the muscle stays constant, a load is moved as the length of the muscle changes (shortens). There are two types of isotonic contractions: concentric and eccentric. A concentric contraction involves the muscle shortening to move a load. An example of this is the biceps brachii muscle contracting when a hand weight is brought upward with increasing muscle tension. As the biceps brachii contract, the angle of the elbow joint decreases as the forearm is brought toward the body. Here, the biceps brachii contracts as sarcomeres in its muscle fibers are shortening and cross-bridges form; the myosin heads pull the actin. An eccentric contraction occurs as the muscle tension diminishes and the muscle lengthens. In this case, the hand weight is lowered in a slow and controlled manner as the amount of cross-bridges being activated by nervous system stimulation decreases. In this case, as tension is released from the biceps brachii, the angle of the elbow joint increases. Eccentric contractions are also used for movement and balance of the body.

An isometric contraction occurs as the muscle produces tension without changing the angle of a skeletal joint. Isometric contractions involve sarcomere shortening and increasing muscle tension, but do not move a load, as the force produced cannot overcome the resistance provided by the load. For example, if one attempts to lift a hand weight that is too heavy, there will be sarcomere activation and shortening to a point, and ever-increasing muscle tension, but no change in the angle of the elbow joint. In everyday living, isometric contractions are active in maintaining posture and maintaining bone and joint stability. However, holding your head in an upright position occurs not because the muscles cannot move the head, but because the goal is to remain stationary and not produce movement. Most actions of the body are the result of a combination of isotonic and isometric contractions working together to produce a wide range of outcomes (Figure 3.9).

Interactive Link

Watch this video for a practical example of the differences between isometric, concentric, and eccentric contractions and the importance of strengthening exercises of all types of contractions.

The Length-Tension Range of a Sarcomere

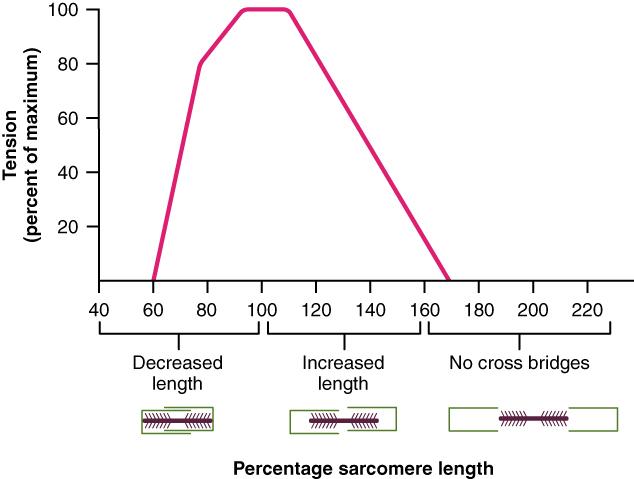

When a skeletal muscle fiber contracts, myosin heads attach to actin to form cross-bridges followed by the thin filaments sliding over the thick filaments as the heads pull the actin, and this results in sarcomere shortening, creating the tension of the muscle contraction. The cross-bridges can only form where thin and thick filaments already overlap, so that the length of the sarcomere has a direct influence on the force generated when the sarcomere shortens. This is called the length-tension relationship.

The ideal length of a sarcomere to produce maximal tension occurs at 80 percent to 120 percent of its resting length, with 100 percent being the state where the medial edges of the thin filaments are just at the most-medial myosin heads of the thick filaments (Figure 3.10). This length maximizes the overlap of actin-binding sites and myosin heads. If a sarcomere is stretched past this ideal length (beyond 120 percent), thick and thin filaments do not overlap sufficiently, which results in less tension produced. If a sarcomere is shortened beyond 80 percent, the zone of overlap is reduced with the thin filaments jutting beyond the last of the myosin heads and shrinks the H zone, which is normally composed of myosin tails. Eventually, there is nowhere else for the thin filaments to go and the amount of tension is diminished. If the muscle is stretched to the point where thick and thin filaments do not overlap at all, no cross-bridges can be formed, and no tension is produced in that sarcomere. This amount of stretching does not usually occur, as accessory proteins and connective tissue oppose extreme stretching.