2.6 Fibrous Joints

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structural features of fibrous joints

- Distinguish between a suture, syndesmosis, and gomphosis

- Give an example of each type of fibrous joint

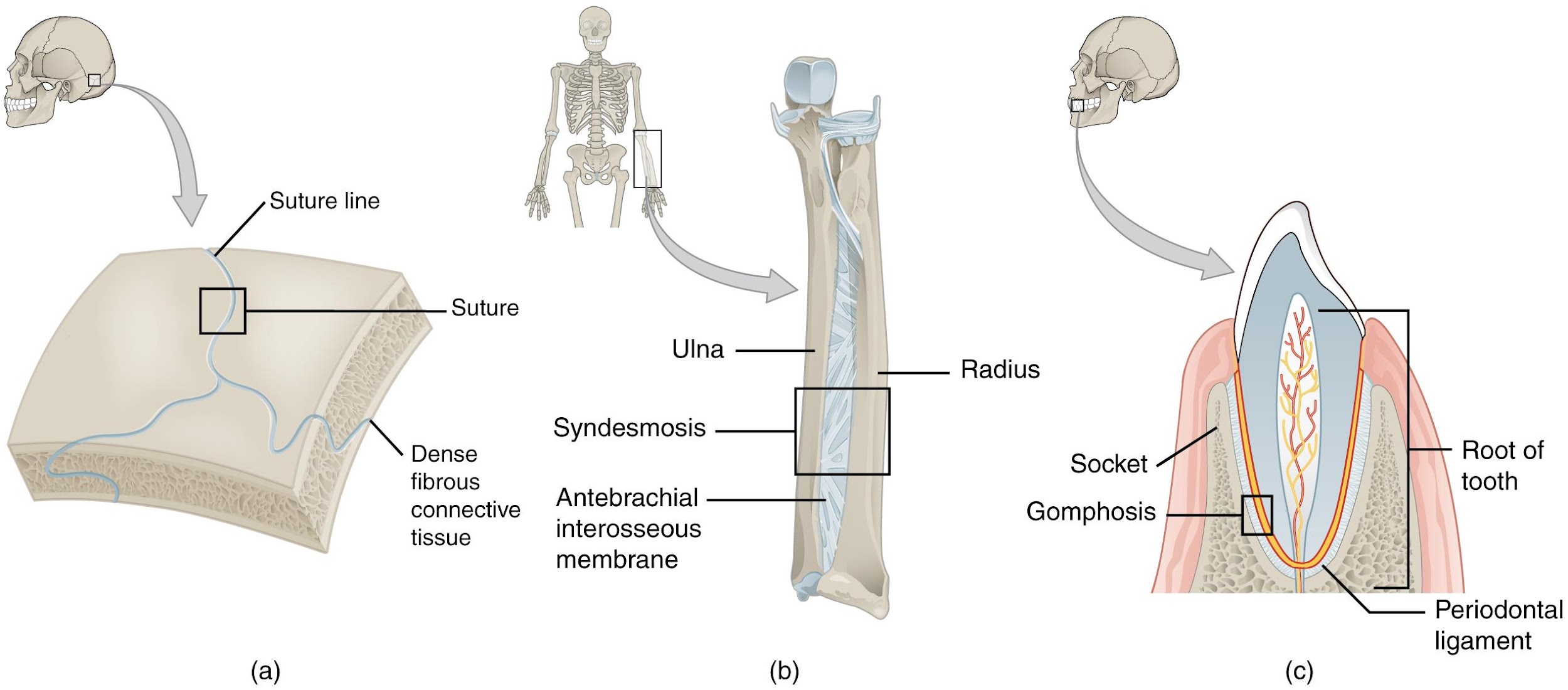

At a fibrous joint, the adjacent bones are directly connected to each other by fibrous connective tissue, and thus the bones do not have a joint cavity between them (Figure 2.18). The gap between the bones may be narrow or wide. There are three types of fibrous joints. A suture is the narrow fibrous joint found between most bones of the skull. At a syndesmosis joint, the bones are more widely separated but are held together by a narrow band of fibrous connective tissue called a ligament or a wide sheet of connective tissue called an interosseous membrane. This type of fibrous joint is found between the shaft regions of the long bones in the forearm and in the leg. Lastly, a gomphosis is the narrow fibrous joint between the roots of a tooth and the bony socket in the jaw into which the tooth fits.

Suture

All the bones of the skull, except for the mandible, are joined to each other by a fibrous joint called a suture. The fibrous connective tissue found at a suture (“to bind or sew”) strongly unites the adjacent skull bones and thus helps to protect the brain and form the face. In adults, the skull bones are closely opposed and fibrous connective tissue fills the narrow gap between the bones. The suture is frequently convoluted, forming a tight union that prevents most movement between the bones. (Figure 2.18a.) Thus, skull sutures are functionally classified as a synarthrosis, although some sutures may allow for slight movements between the cranial bones.

Syndesmosis

A syndesmosis (“fastened with a band”) is a type of fibrous joint in which two parallel bones are united to each other by fibrous connective tissue. The gap between the bones may be narrow, with the bones joined by ligaments, or the gap may be wide and filled in by a broad sheet of connective tissue called an interosseous membrane.

In the forearm, the wide gap between the shaft portions of the radius and ulna bones are strongly united by an interosseous membrane (Figure 2.18b). Similarly, in the leg, the shafts of the tibia and fibula are also united by an interosseous membrane. In addition, at the distal tibiofibular joint, the articulating surfaces of the bones lack cartilage and the narrow gap between the bones is anchored by fibrous connective tissue and ligaments on both the anterior and posterior aspects of the joint. Together, the interosseous membrane and these ligaments form the tibiofibular syndesmosis.

The syndesmoses found in the forearm and leg serve to unite parallel bones and prevent their separation. However, a syndesmosis does not prevent all movement between the bones, and thus this type of fibrous joint is functionally classified as an amphiarthrosis. In the leg, the syndesmosis between the tibia and fibula strongly unites the bones, allows for little movement, and firmly locks the talus bone in place between the tibia and fibula at the ankle joint. This provides strength and stability to the leg and ankle, which are important during weight bearing. In the forearm, the interosseous membrane is flexible enough to allow for rotation of the radius bone during forearm movements. Thus in contrast to the stability provided by the tibiofibular syndesmosis, the flexibility of the antebrachial interosseous membrane allows for the much greater mobility of the forearm.

The interosseous membranes of the leg and forearm also provide areas for muscle attachment.

Gomphosis

A gomphosis (“fastened with bolts”) is the specialized fibrous joint that anchors the root of a tooth into its bony socket within the maxillary bone (upper jaw) or mandible bone (lower jaw) of the skull (Figure 2.18c). Due to the immobility of a gomphosis, this type of joint is functionally classified as a synarthrosis.