3.2 Skeletal Muscle

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the layers of connective tissues packaging skeletal muscle

- Explain how muscles work with tendons to move the body

- Identify areas of the skeletal muscle fibers

- Describe excitation-contraction coupling

The best-known feature of skeletal muscle is its ability to contract and cause movement.. Small, constant adjustments of the skeletal muscles are needed to hold a body upright or balanced in any position. Muscles also prevent excess movement of the bones and joints, maintaining skeletal stability and preventing skeletal structure damage or deformation. Skeletal muscles also protect internal organs (particularly abdominal and pelvic organs) by acting as an external barrier or shield to external trauma and by supporting the weight of the organs.

Skeletal muscles contribute to the maintenance of homeostasis in the body by generating heat. Muscle contraction requires energy, and when ATP is broken down, heat is produced. This heat is very noticeable during exercise, when sustained muscle movement causes body temperature to rise, and in cases of extreme cold, when shivering produces random skeletal muscle contractions to generate heat.

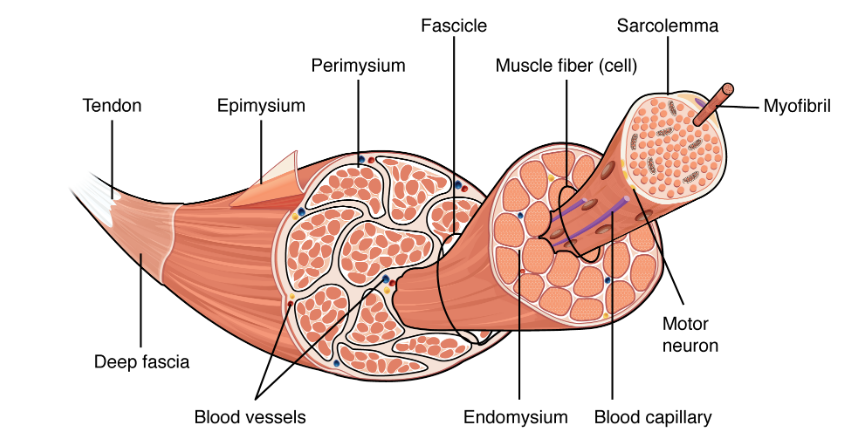

Each skeletal muscle is an organ that consists of various integrated tissues. These tissues include the skeletal muscle fibers, blood vessels, nerve fibers, and connective tissue. Each skeletal muscle has three layers of connective tissue (called “mysia”) that enclose it and provide structure to the muscle as a whole, and also compartmentalize the muscle fibers within the muscle (Figure 3.3). Each muscle is wrapped in a sheath of dense, irregular connective tissue called the epimysium, which allows a muscle to contract and move powerfully while maintaining its structural integrity. The epimysium also separates muscle from other tissues and organs in the area, allowing the muscle to move independently.

Inside each skeletal muscle, muscle fibers are organized into individual bundles, each called a fascicle, by a middle layer of connective tissue called the perimysium. Inside each fascicle, each muscle fiber is encased in a thin connective tissue layer of collagen and reticular fibers called the endomysium. The endomysium contains the extracellular fluid and nutrients to support the muscle fiber.

In skeletal muscles that work with tendons to pull on bones, the collagen in the three tissue layers (the mysia) intertwines with the collagen of a tendon. At the other end of the tendon, it fuses with the periosteum coating the bone. The tension created by contraction of the muscle fibers is then transferred through the mysia, to the tendon, and then to the periosteum to pull on the bone for movement of the skeleton. In other places, the mysia may fuse with a broad, tendon-like sheet called an aponeurosis, or to fascia, the connective tissue between skin and bones. The broad sheet of connective tissue in the lower back that the latissimus dorsi muscles (the “lats”) fuse into is an example of an aponeurosis.

Skeletal Muscle Fibers

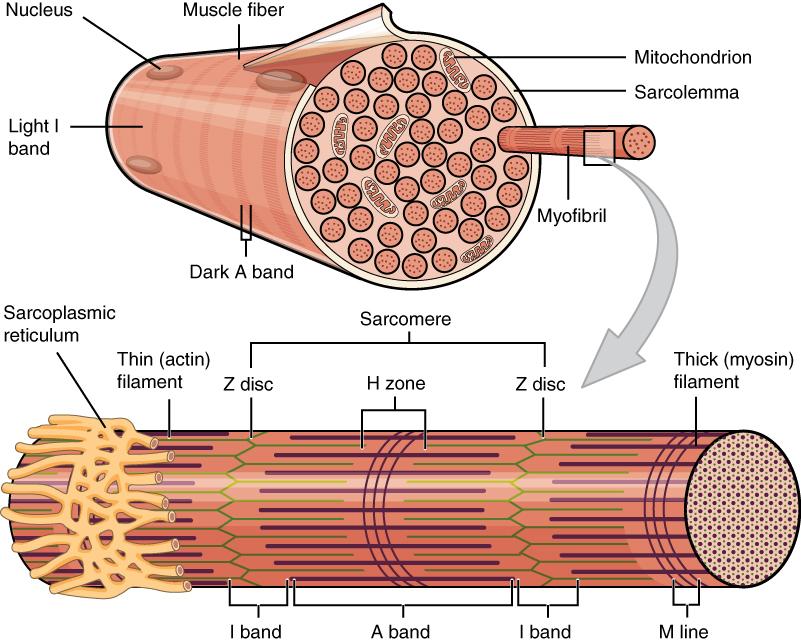

Because skeletal muscle cells are long and cylindrical, they are commonly referred to as muscle fibers. Some other terminology associated with muscle fibers is rooted in the Greek sarco, which means “flesh.” The plasma membrane of muscle fibers is called the sarcolemma, and the cytoplasm is referred to as sarcoplasm (Figure 3.4). As will soon be described, the functional unit of a skeletal muscle fiber is the sarcomere, a highly organized arrangement of the contractile myofilaments actin (thin filament) and myosin (thick filament), along with other support proteins.

The Sarcomere

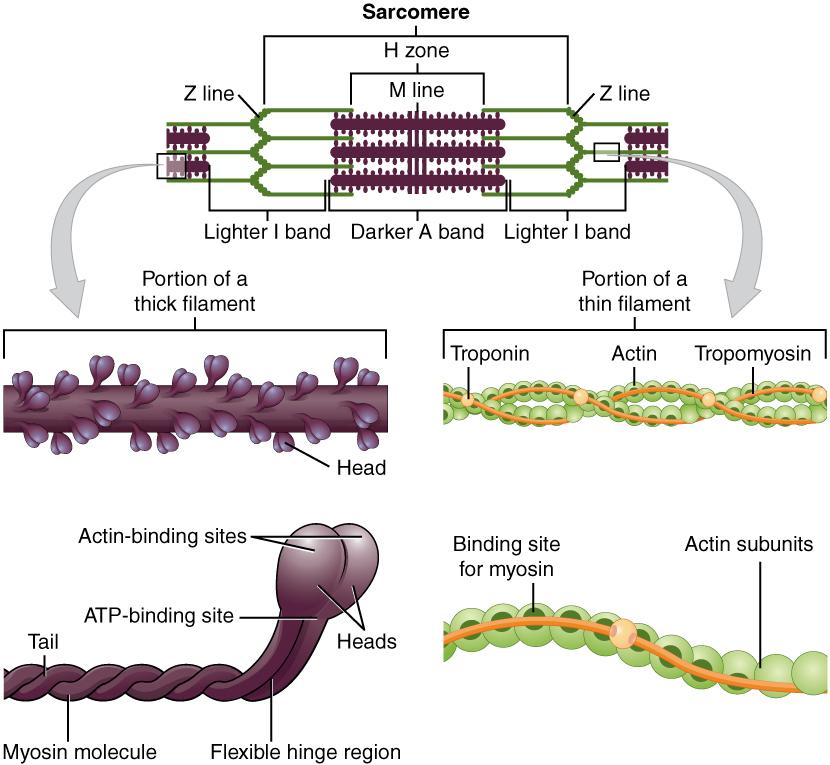

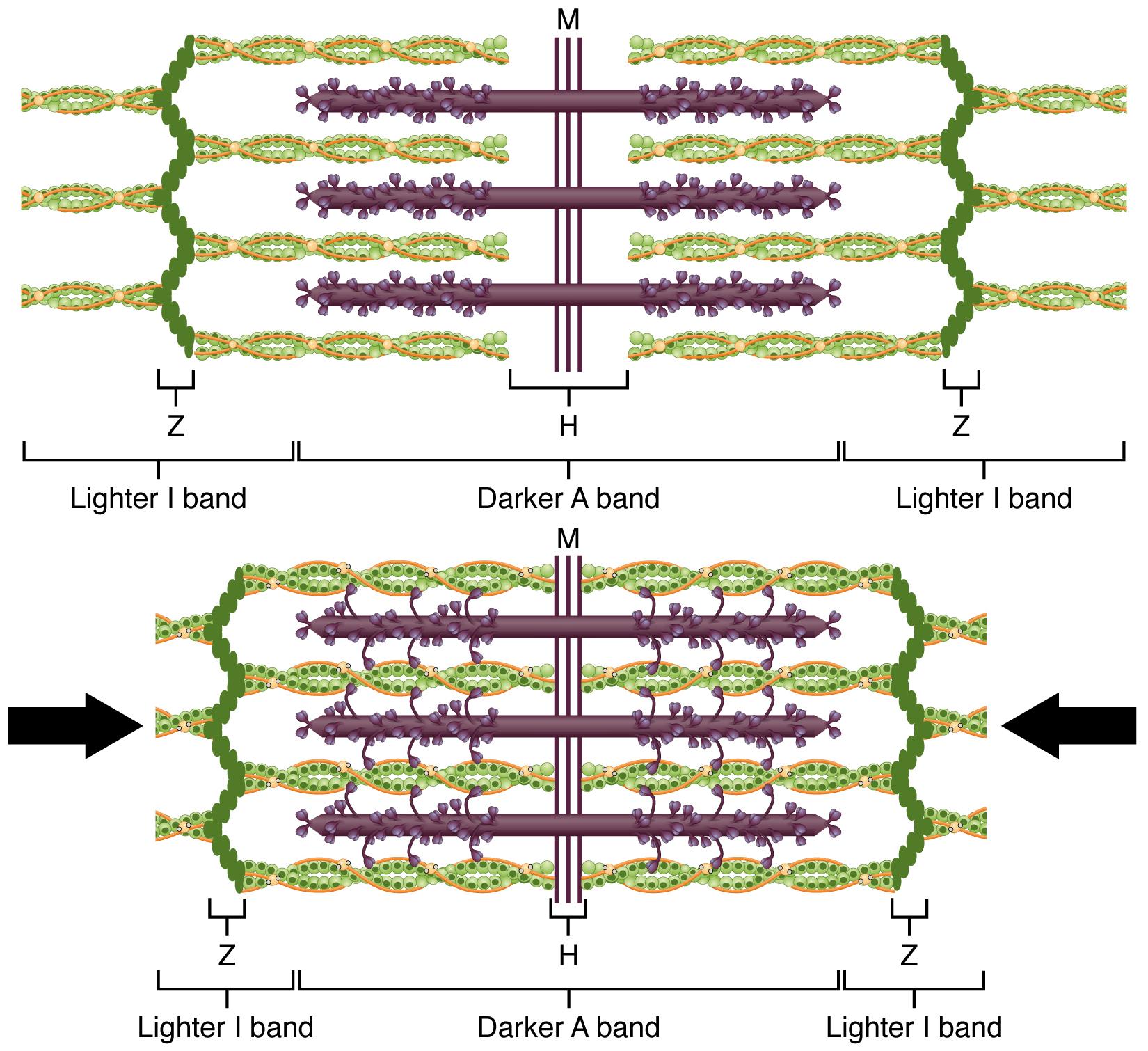

The striated appearance of skeletal muscle fibers is due to the arrangement of the myofilaments of actin and myosin in sequential order from one end of the muscle fiber to the other. Each packet of these microfilaments and their regulatory proteins, troponin and tropomyosin (along with other proteins) is called a sarcomere.

The sarcomere is the functional unit of the muscle fiber. The sarcomere itself is bundled within the myofibril that runs the entire length of the muscle fiber and attaches to the sarcolemma at its end. As myofibrils contract, the entire muscle cell contracts. Because myofibrils are only approximately 1.2 μm in diameter, hundreds to thousands (each with thousands of sarcomeres) can be found inside one muscle fiber. Each sarcomere is bordered by structures called Z-discs (also called Z-lines), to which the actin myofilaments are anchored (Figure 3.5). Because the actin form strands that are thinner than the myosin, it is called the thin filament of the sarcomere. Likewise, because the myosin strands and their multiple heads (projecting from the center of the sarcomere toward the Z-discs) have more mass and are thicker, they are called the thick filament of the sarcomere.

The Neuromuscular Junction

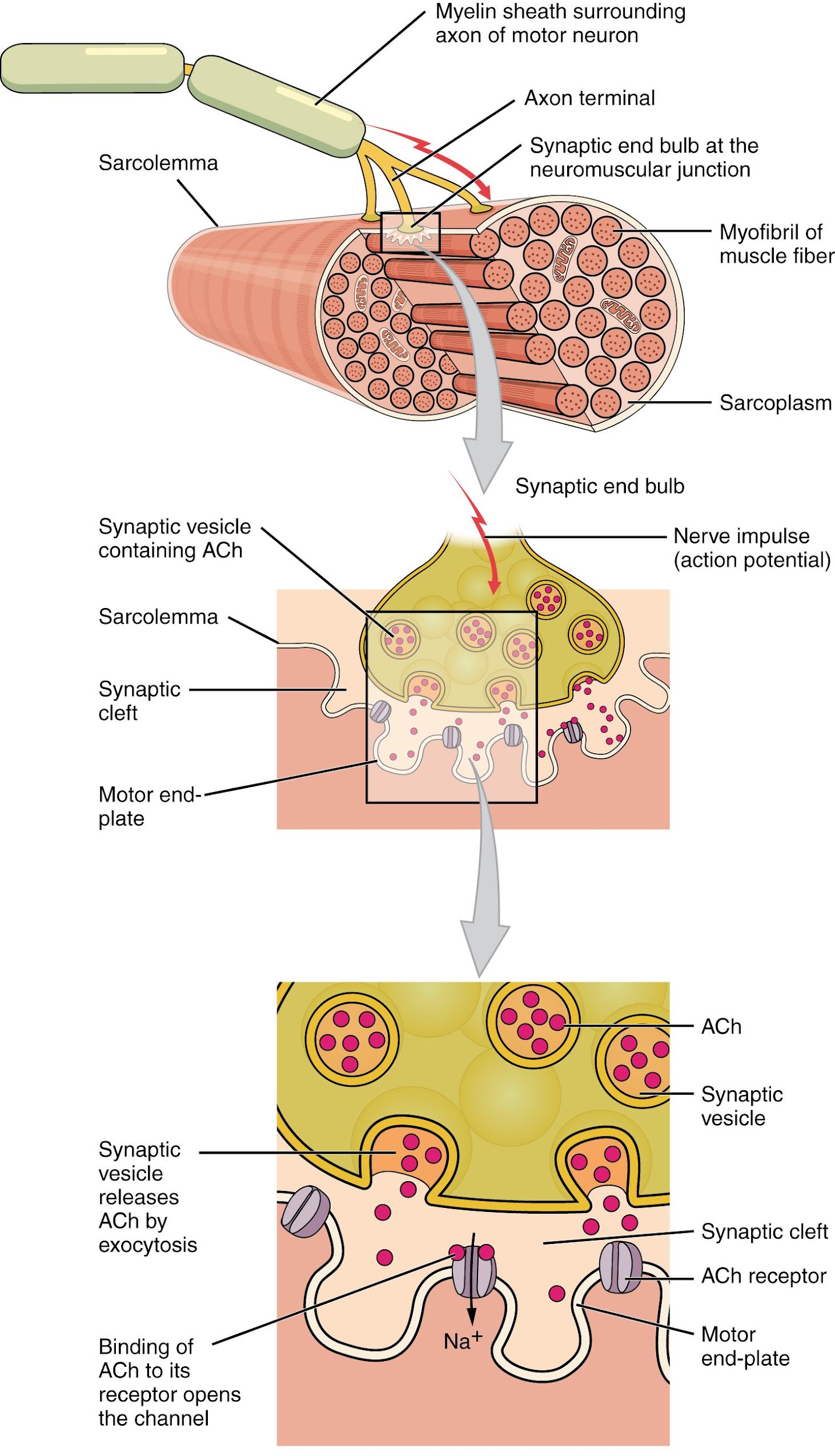

Another specialization of the skeletal muscle is the site where a motor neuron’s terminal meets the muscle fiber—called the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). This is where the muscle fiber first responds to signaling by the motor neuron. Every skeletal muscle fiber in every skeletal muscle is innervated by a motor neuron at the NMJ. Excitation signals from the neuron are the only way to functionally activate the fiber to contract.

Excitation-Contraction Coupling

All living cells have membrane potentials, or electrical gradients across their membranes. The inside of the membrane is usually around -60 to -90 mV, relative to the outside. This is referred to as a cell’s membrane potential. Neurons and muscle cells can use their membrane potentials to generate electrical signals. They do this by controlling the movement of charged particles, called ions, across their membranes to create electrical currents. This is achieved by opening and closing specialized proteins in the membrane called ion channels. Although the currents generated by ions moving through these channel proteins are very small, they form the basis of both neural signaling and muscle contraction.

Both neurons and skeletal muscle cells are electrically excitable, meaning that they are able to generate action potentials. An action potential is a special type of electrical signal that can travel along a cell membrane as a wave. This allows a signal to be transmitted quickly and faithfully over long distances.

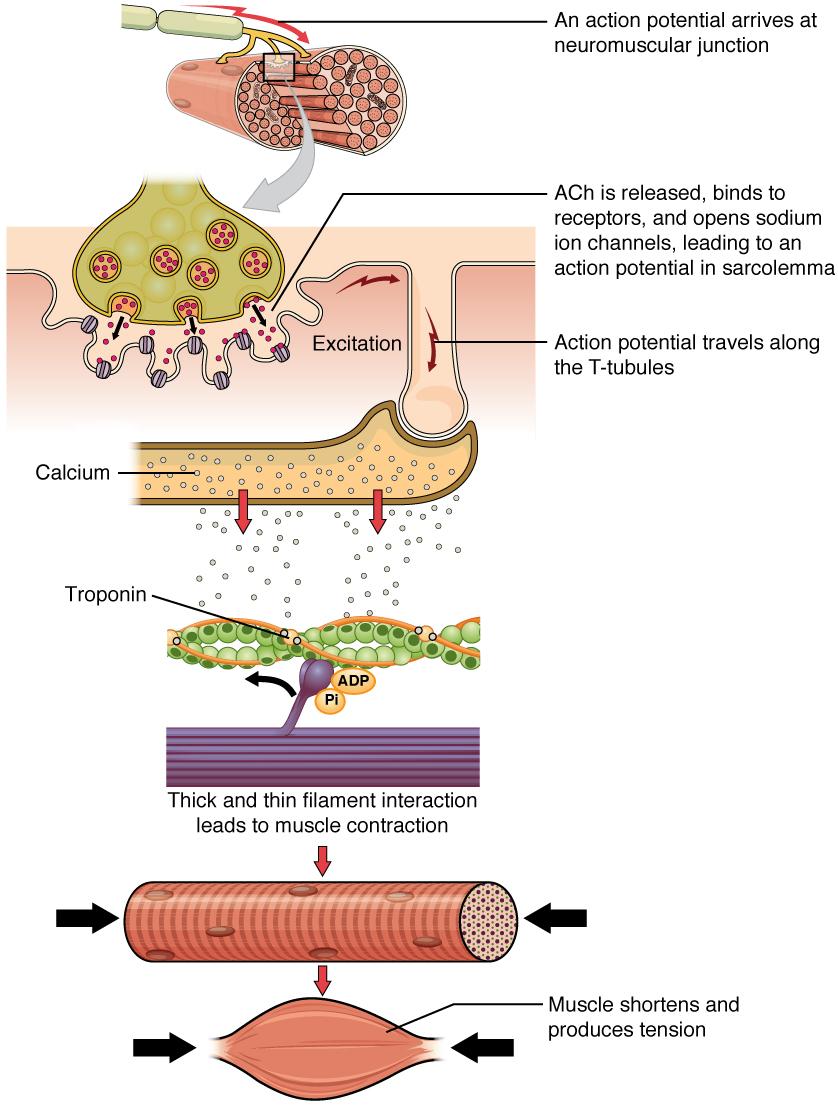

Although the term excitation-contraction coupling confuses or scares some students, it comes down to this: for a skeletal muscle fiber to contract, its membrane must first be “excited”—in other words, it must be stimulated to fire an action potential. The muscle fiber action potential, which sweeps along the sarcolemma as a wave, is “coupled” to the actual contraction through the release of calcium ions (Ca++).

The motor neurons that tell the skeletal muscle fibers to contract originate in the spinal cord, with a smaller number located in the brainstem for activation of skeletal muscles of the face, head, and neck. These neurons have long processes, called axons, which are specialized to transmit action potentials long distances— in this case, all the way from the spinal cord to the muscle itself (which may be up to three feet away). The axons of multiple neurons bundle together to form nerves, like wires bundled together in a cable.

Signaling begins when a neuronal action potential travels along the axon of a motor neuron, and then along the individual branches to terminate at the NMJ. At the NMJ, the axon terminal releases a chemical messenger, or neurotransmitter, called acetylcholine (ACh). The ACh molecules diffuse across a minute space called the synaptic cleft and bind to ACh receptors located within the motor end-plate of the sarcolemma on the other side of the synapse. Once ACh binds, a channel in the ACh receptor opens and positively charged ions can pass through into the muscle fiber, causing it to depolarize, meaning that the membrane potential of the muscle fiber becomes less negative (closer to zero.)

As the membrane depolarizes, another set of ion channels called voltage-gated sodium channels are triggered to open. Sodium ions enter the muscle fiber, and an action potential rapidly spreads (or “fires”) along the entire membrane to initiate excitation-contraction coupling. Things happen very quickly in the world of excitable membranes (just think about how quickly you can snap your fingers as soon as you decide to do it).

Propagation of an action potential along the sarcolemma is the excitation portion of excitation-contraction coupling. Recall that this excitation actually triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca++). It is the arrival of Ca++ in the sarcoplasm that initiates contraction of the muscle fiber by its contractile units, or sarcomeres. This is described next in the sliding filament model of contraction.

The Sliding Filament Model of Contraction

When signaled by a motor neuron, a skeletal muscle fiber contracts as the thin filaments are pulled and then slide past the thick filaments within the fiber’s sarcomeres. This process is known as the sliding filament model of muscle contraction (Figure 3.7).

Tropomyosin is a protein that winds around actin filament and covers the myosin-binding sites to prevent actin from binding to myosin. Tropomyosin binds to troponin to form a troponin-tropomyosin complex. The troponin-tropomyosin complex prevents the myosin “heads” from binding to the active sites on the actin microfilaments. Troponin also has a binding site for Ca++ ions.

To initiate muscle contraction, Ca++ binds to troponin, causing tropomyosin to slide away from the myosin-binding sites on the actin. This allows the myosin heads to bind to these exposed binding sites and form cross-bridges. The thin filaments are then pulled by the myosin heads to slide past the thick filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. But each head can only pull a very short distance before it has reached its limit and must be “re-cocked” before it can pull again, a step that requires ATP.

For thin filaments to continue to slide past thick filaments during muscle contraction, myosin heads must pull the actin at the binding sites, detach, re-cock, attach to more binding sites, pull, detach, re-cock, etc. This repeated movement is known as the cross-bridge cycle. This motion of the myosin heads is similar to the oars when an individual rows a boat: The paddle of the oars (the myosin heads) pull, are lifted from the water (detach), repositioned (re-cocked) and then immersed again to pull. Each cycle requires energy, and the action of the myosin heads in the sarcomeres repetitively pulling on the thin filaments also requires energy, which is provided by ATP.

Relaxation of a Skeletal Muscle

Relaxing skeletal muscle fibers, and ultimately, the skeletal muscle, begins with the motor neuron, which stops releasing its chemical signal, ACh, into the synapse at the NMJ. The muscle fiber will repolarize, which stops the release of Ca++. ATP-driven pumps will move Ca++ out of the sarcoplasm. This results in the “reshielding” of the actin-binding sites on the thin filaments. Without the ability to form cross-bridges between the thin and thick filaments, the muscle fiber loses its tension and relaxes.