4.4 The Action Potential

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the components of the membrane that establish the resting membrane potential

- Describe the changes that occur to the membrane that result in the action potential

The functions of the nervous system—sensation, integration, and response—depend on the functions of the neurons underlying these pathways. To understand how neurons are able to communicate, it is necessary to describe the role of an excitable membrane in generating these signals. The basis of this communication is the action potential, which demonstrates how changes in the membrane can constitute a signal. Looking at the way these signals work in more variable circumstances involves a look at graded potentials, which will be covered in the next section.

Electrically Active Cell Membranes

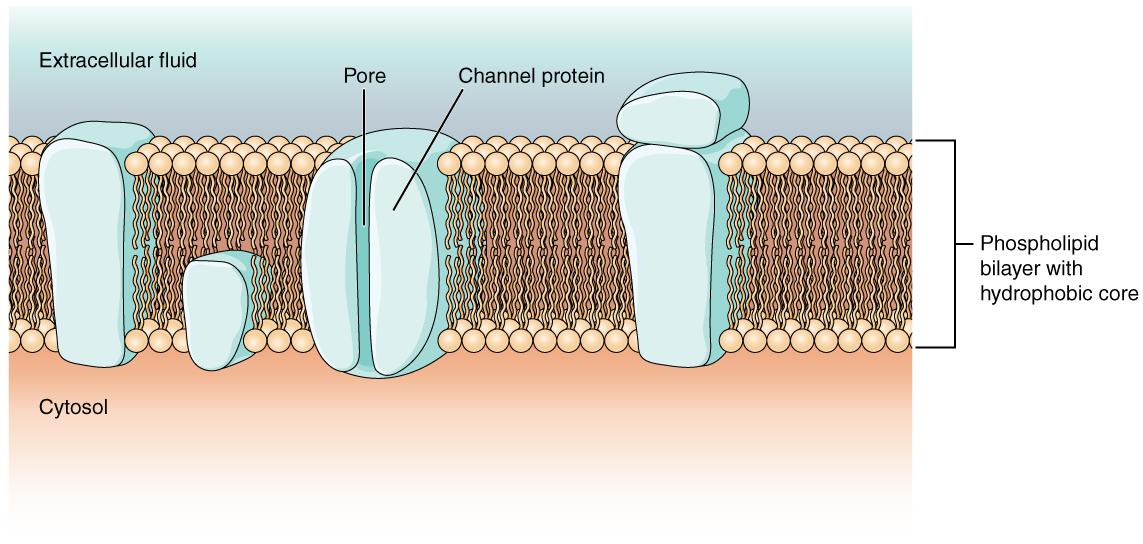

Most cells in the body make use of charged particles, ions, to build up a charge across the cell membrane. The cell membrane is primarily responsible for regulating what can cross the membrane and what stays on only one side. Charged particles cannot pass through the cell membrane without assistance (Figure 4.12). Proteins embedded into the cell membrane make this possible. Of special interest is the carrier protein referred to as the sodium/potassium pump that moves sodium ions (Na+) out of a cell and potassium ions (K+) into a cell, thus regulating ion concentration on both sides of the cell membrane.

The Membrane Potential

The electrical state of the cell membrane can have several variations. These are all variations in the membrane potential. A potential is a distribution of charge across the cell membrane, measured in millivolts (mV). The standard is to compare the inside of the cell relative to the outside, so the membrane potential is a value representing the charge on the intracellular side of the membrane based on the outside being zero, relatively speaking.

Before action potentials can be described, the resting state of the membrane must be explained. When the cell is at rest, and the protein channels are closed, ions are distributed across the membrane in a very predictable way. The concentration of Na+ outside the cell is 10 times greater than the concentration inside. Also, the concentration of K+ inside the cell is greater than outside.

With the ions distributed across the membrane at these concentrations, the difference in charge is measured at -70 mV, the value described as the resting membrane potential. The exact value measured for the resting membrane potential varies between cells, but -70 mV is most commonly used as this value.

The Action Potential

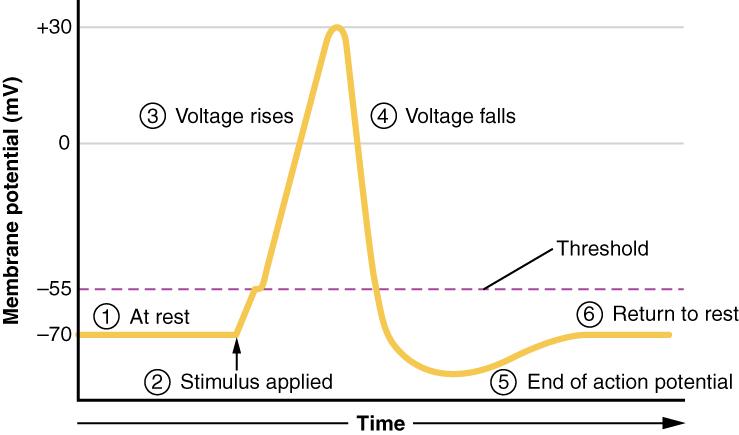

Resting membrane potential describes the steady state of the cell. Without any outside influence, it will not change. To get an electrical signal started, the membrane potential has to change.

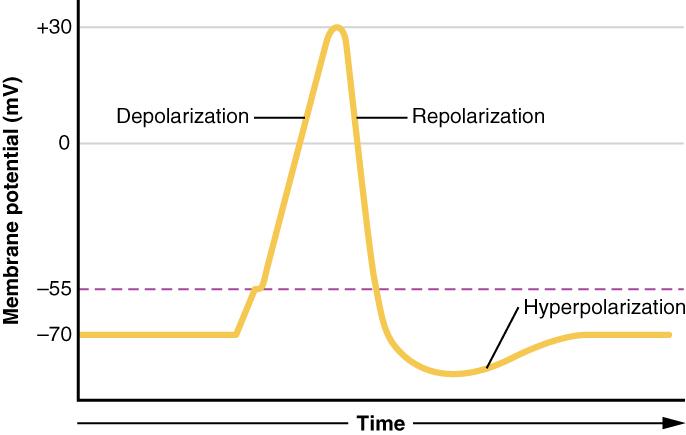

This starts with a channel opening for Na+ in the membrane. Because the concentration of Na+ is higher outside the cell than inside the cell by a factor of 10, ions will rush into the cell that are driven largely by the concentration gradient. Because sodium is a positively charged ion, it will change the relative voltage immediately inside the cell relative to immediately outside. The resting potential is the state of the membrane at a voltage of -70 mV, so the positively charge sodium ions entering the cell will cause it to become less negative. This is known as depolarization, meaning the membrane potential moves toward zero.

The concentration gradient for Na+ is so strong that it will continue to enter the cell even after the membrane potential has become zero, so that the voltage immediately around the pore begins to become positive. The electrical gradient also plays a role, as negative proteins below the membrane attract the sodium ion. The membrane potential will reach +30 mV by the time sodium has entered the cell.

As the membrane potential reaches +30 mV, other voltage-gated channels are opening in the membrane. These channels are specific for the potassium ion. A concentration gradient acts on K+, as well. As K+ starts to leave the cell, taking a positive charge with it, the membrane potential begins to move back toward its resting voltage. This is called repolarization, meaning that the membrane voltage moves back toward the -70 mV value of the resting membrane potential.

Repolarization returns the membrane potential to the -70 mV value that indicates the resting potential, but it actually overshoots that value. Potassium ions reach equilibrium when the membrane voltage is below -70 mV, so a period of hyperpolarization occurs while the K+ channels are open. Those K+ channels are slightly delayed in closing, accounting for this short overshoot.

What has been described here is the action potential, which is presented as a graph of voltage over time in Figure 4.13. It is the electrical signal that nervous tissue generates for communication. The change in the membrane voltage from -70 mV at rest to +30 mV at the end of depolarization is a 100 mV change.

The question is, now, what initiates the action potential? The description above conveniently glosses over that point. But it is vital to understanding what is happening. The membrane potential will stay at the resting voltage until something changes. The description above just says that a Na+ channel opens. Now, to say “a channel opens” does not mean that one individual transmembrane protein changes. Instead, it means that one kind of channel opens. A Na+ channel will open when a neurotransmitter binds to it or a Na+ channel will open when a physical stimulus affects a sensory receptor (like pressure applied to the skin compresses a touch receptor). Whether it is a neurotransmitter binding to its receptor protein or a sensory stimulus activating a sensory receptor cell, some stimulus gets the process started. Sodium starts to enter the cell and the membrane becomes less negative.

As the sodium enters, the membrane potential becomes less negative. The amount of sodium that enters at this point is related to the size of the stimulus. This is a graded potential. When the membrane potential reaches threshold (-55 mV), more sodium channels open, and an action potential will be initiated.

Action potentials follow an All-or-Nothing law—it either happens or it does not. If the threshold is not reached, then no action potential occurs. If depolarization reaches -55 mV, then the action potential continues and runs all the way to +30 mV, at which K+ causes repolarization, including the hyperpolarizing overshoot. Also, those changes are the same for every action potential, which means that once the threshold is reached, the exact same thing happens. A stronger stimulus, which might depolarize the membrane well past threshold, will not make a “bigger” action potential. Action potentials are “all or none.” Either the membrane reaches the threshold and everything occurs as described above, or the membrane does not reach the threshold and nothing else happens. All action potentials peak at the same voltage (+30 mV), so one action potential is not bigger than another. Stronger stimuli will initiate multiple action potentials more quickly, but the individual signals are not bigger.

Interactive Link

Watch this video that provides an animation of the process of an action potential and the flow of ions that are responsible for the action potential.