Chapter 8: Organizational Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify the three levels of management and the responsibilities at each level.

- Discuss various options for organizing a business, and create an organization chart.

- Explain how specialization helps make organizations more efficient.

- Discuss the different ways that an organization can departmentalize.

- Explain other key terms related to this chapter such as chain of command, a delegation of authority, and span of control.

Organizing

If you read Chapter 7: Management and Leadership, you will recall developing a strategic plan for your new company, Notes-4-You. Once a business has completed the planning process, it will need to organize the company so that it can implement that plan. A manager engaged in organizing allocates resources (people, equipment, and money) to achieve a company’s objectives. Successful managers make sure that all the activities identified in the planning process are assigned to some person, department, or team and that everyone has the resources needed to perform assigned activities.

Levels of Management: How Managers Are Organized

A typical organization has several layers of management. Think of these layers as forming a pyramid, with top managers occupying the narrow space at the peak, first-line managers the broad base, and middle managers the levels in between.

As you move up the pyramid, management positions get more demanding, but they carry more authority and responsibility (along with more power, prestige, and pay). Top managers spend most of their time in planning and decision-making, while first-line managers focus on day-to-day operations. For obvious reasons, there are far more people with positions at the base of the pyramid than there are at the other two levels. Let’s look at each management level in more detail.

| Top managers | Are responsible for the health and performance of the organization. They set the objectives, or performance targets, designed to direct all the activities that must be performed if the company is going to fulfill its mission. Top-level executives routinely scan the external environment for opportunities and threats, and they redirect the club’s efforts when needed. They spend a considerable portion of their time planning and making major decisions. They represent the company in important dealings with other businesses and government agencies, and they promote it to the public. Job titles at this level typically include chief executive officer (CEO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief operating officer (COO), president, and vice president. In the case of golf courses, the top manager is the liaison between the owner, board of directors and the members/staff. |

|---|---|

| Middle managers | Are at the center of the management hierarchy: they report to top management and oversee the activities of first-line managers. They’re responsible for developing and implementing activities and allocating the resources needed to achieve the objectives set by top management. Common job titles include Head Golf professional, Food and Beverage Manager, Executive Chef and Golf course Superintendent |

| First-line managers | Supervise employees and coordinate their activities to make sure that the work performed throughout the company is consistent with the plans of both top and middle management. It’s at this level that most people acquire their first managerial experience. The job titles vary considerably but include such designations as Assistant or Associate golf professional, assistant to the food and beverage manager, first or second assistant to the golf course superintendent or sous-chef. |

Notes-4-You

Let’s take a quick survey of the management hierarchy at Notes-4-You. As president, you are a member of top management, and you’re responsible for the overall performance of your company. You spend much of your time setting performance targets, to ensure that the company meets the goals you’ve set for it— increased sales, higher-quality notes, and timely distribution.

Several middle managers report to you, including your operations manager. As a middle manager, this individual focuses on implementing two of your objectives: producing high-quality notes and distributing them to customers in a timely manner. To accomplish this task, the operations manager oversees the work of two first-line managers—the note-taking supervisor and the copying supervisor. Each first-line manager supervises several non-managerial employees to make sure that their work is consistent with the plans devised by the top and middle management.

Organizational Structure: How Companies Get the Job Done

Building an organizational structure engages managers in two activities: job specialization (dividing tasks into jobs) and departmentalization (grouping jobs into units). An organizational structure outlines the various roles within an organization, which positions report to which, and how an organization will departmentalize its work. Take note that an organizational structure is an arrangement of positions that are most appropriate for your company at a specific point in time. Given the rapidly changing environment in which businesses operate, a structure that works today might be outdated tomorrow. That’s why you hear so often about companies restructuring—altering existing organizational structures to become more competitive once conditions have changed. Let’s now look at how the processes of specialization and departmentalization are accomplished.

Specialization

Organizing activities into clusters of related tasks that can be handled by certain individuals or groups is called specialization. This aspect of designing an organizational structure is twofold:

- Identify the activities that need to be performed in order to achieve organizational goals.

- Break down these activities into tasks that can be performed by individuals or groups of employees.

Specialization has several advantages. First and foremost, it leads to efficiency. Specialization results in jobs that are easier to learn and roles that are clearer to employees. An example of this are workers who have expertise in areas such as culinary, teaching golf, equipment operation on the grounds crew, etc. But the approach has disadvantages, too. Doing the same thing over and over sometimes leads to boredom and may eventually leave employees dissatisfied with their jobs. Before long, companies may notice decreased performance and increased absenteeism and turnover (the percentage of workers who leave an organization and must be replaced). It is important that the top and middle management keep the job positions engaging. One way to accomplish this is through “job-rotation”

Departmentalization

The next step in designing an organizational structure is departmentalization—grouping specialized jobs into meaningful units. Depending on the organization and the size of the work units, they may be called divisions, departments, or just plain groups.

Traditional groupings of jobs result in different organizational structures, and for the sake of simplicity, we’ll focus on two types—functional and divisional organizations.

- A functional organization groups together people who have comparable skills and perform similar tasks. This form of organization is fairly typical for small to medium-size companies, which group their people by business functions: accountants are grouped together, as are people in finance, operations, marketing and sales, human resources, production, and research and development. Each unit is headed by an individual with expertise in the unit’s particular function. For example, Pro Shop, Grounds Operation, Administration, Food/Beverage (Front and Back of House).

There are a number of advantages to the functional approach. The structure is simple to understand and enables the staff to specialize in particular areas; everyone in the grounds department would probably have similar interests and expertise. But homogeneity also has drawbacks: it can hinder communication and decision-making between units and even promote interdepartmental conflict. The grounds department, for example, might butt heads with the pro shop because the grounds crew’s goal is to get the daily maintenance routines completed, however they may disrupt play on the golf course, which could lead to complaints to the proshop by members and guests

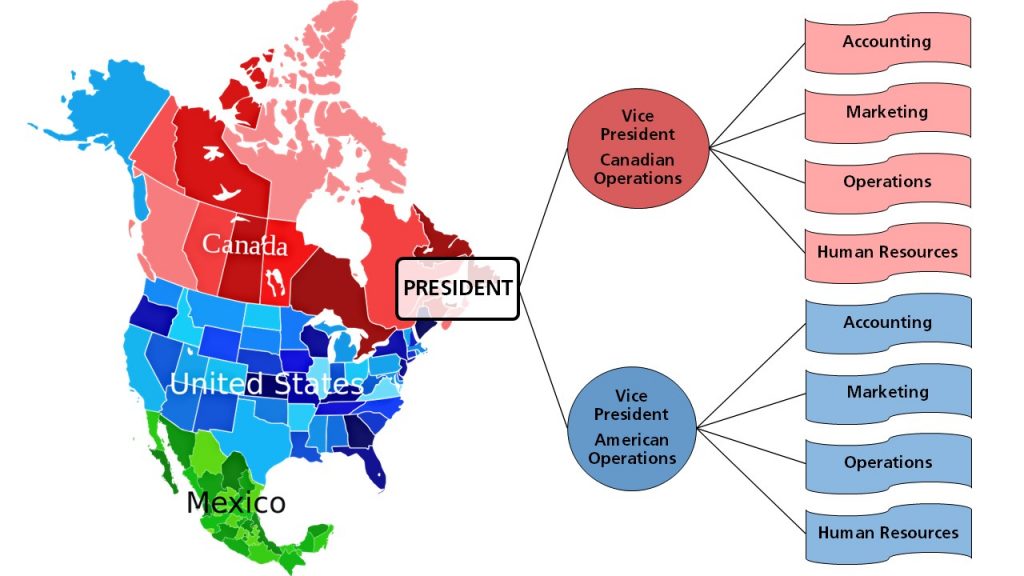

Large companies often find it unruly to operate as one large unit under a functional organizational structure. Sheer size makes it difficult for managers to oversee operations and serve customers. To rectify this problem, most large companies are structured as divisional organizations. They are similar in many respects to stand-alone companies, except that certain common tasks, like legal work, tends to be centralized at the headquarters level. Each division functions relatively autonomously because it contains most of the functional expertise (production, marketing, accounting, finance, human resources) needed to meet its objectives. The challenge is to find the most appropriate way of structuring operations to achieve overall company goals. Toward this end, divisions can be formed according to products, customers, processes, or geography. A good example of this is Golf North Properties or Clublink, where they have several golf courses with one central headquarters.

The Organization Chart

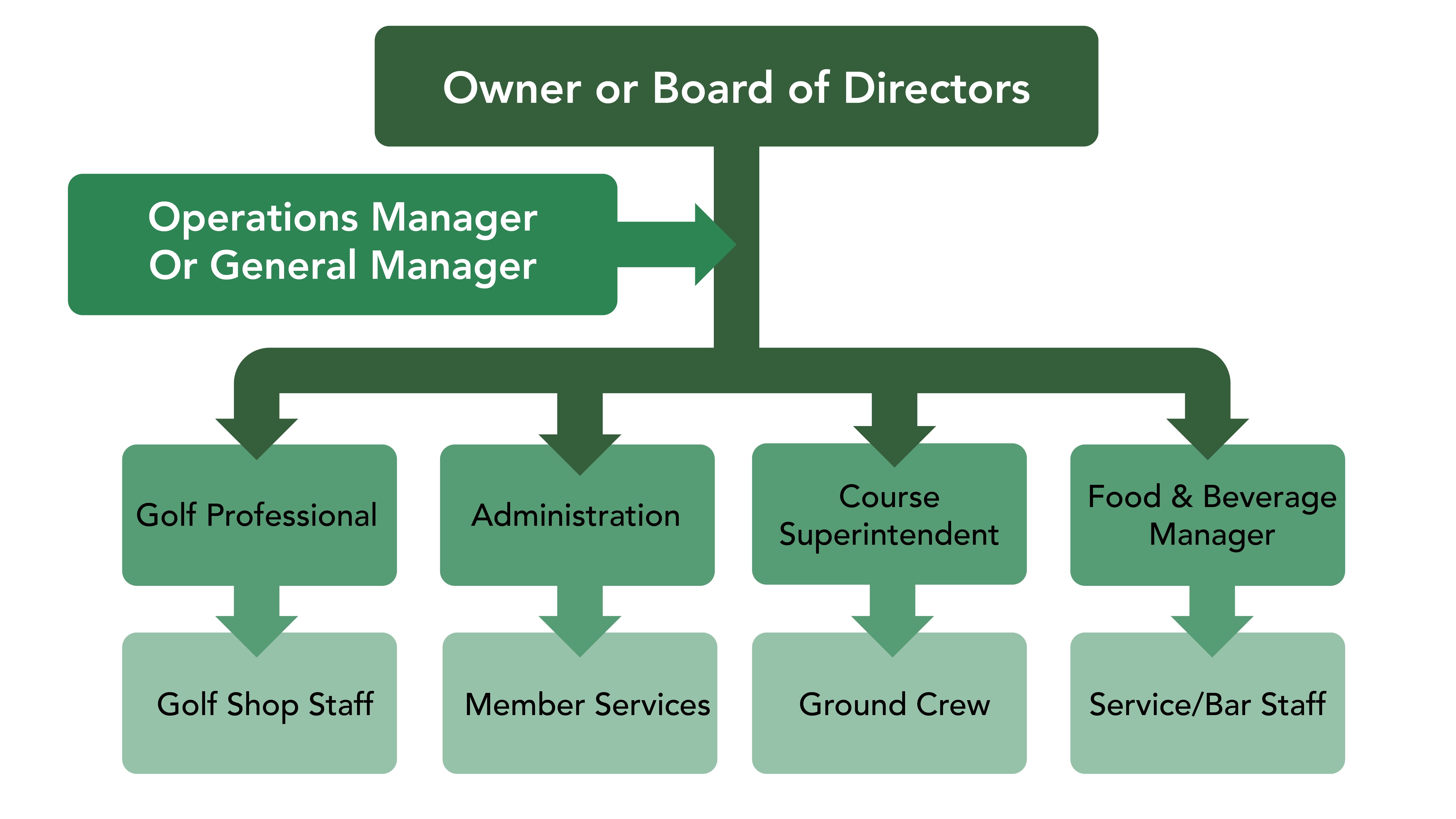

Once an organization has set its structure, it can represent that structure in an organization chart: a diagram delineating the interrelationships of positions within the organization. Here is an example of this type of organization chart as it pertains to the golf and club industry:

Imagine putting yourself at the top of the chart, as the company’s owner. You would then fill in the level directly below with the name of the general manager. Then the names of the people who work in each functional area: golf professional, administration, course superintendent and food and beverage manager

Although the structure suggests that you will communicate only with the general manager, this isn’t the way things normally work in practice. Behind every formal communication network there lies a network of informal communications—unofficial relationships among members of an organization. You might find that over time, you receive communications directly from members of the service staff; in fact, you might encourage this line of communication.

Over time, some golf course operations revise their organizational structures to accommodate growth and changes in the external environment. It’s not uncommon, for example, for a golf operation to adopt a functional structure in its early years. Then, as it becomes bigger and more complex, it might move to a divisional structure—perhaps to accommodate new services or to become more responsive to certain member/customers or geographical areas. Some golf course operations might ultimately rely on a combination of functional and divisional structures. This could be a good approach for Club Link that operates in both the United States and Canada. An outline of this organization chart might look like the following diagram.

Chain of Command

The vertical connecting lines in the organization chart show the club’s chain of command: the authority relationships among people working at different levels of the organization. That is to say, they show who reports to whom. When you’re examining an organization chart, you’ll probably want to know whether each person reports to one or more supervisors: to what extent, in other words, is there unity of command? To understand why unity of command is an important organizational feature, think about it from a personal standpoint. Would you want to report to more than one boss? What happens if you get conflicting directions? Whose directions would you follow?

Span of Control

Another thing to notice about a firm’s chain of command is the number of layers between the top managerial position and the lowest managerial level. As a rule, new organizations have only a few layers of management—an organizational structure that’s often called flat. Let’s say, for instance, that a member of the Notes-4-You sales staff wanted to express concern about slow sales among a certain group of students. That person’s message would have to filter upward through only two management layers—the sales supervisor and the marketing manager—before reaching the president.

As a company grows, however, it tends to add more layers between the top and the bottom; that is, it gets taller. Added layers of management can slow down communication and decision-making, causing the organization to become less efficient and productive. That’s one reason why many of today’s organizations are restructuring to become flattered.

There are trade-offs between the advantages and disadvantages of flat and tall organizations. Companies determine which trade-offs to make according to a principle called span of control, which measures the number of people reporting to a particular manager. If, for example, you remove layers of management to make your organization flatter, you end up increasing the number of people reporting to a particular supervisor.

Notes-4-You

So what’s better—a narrow span of control (with few direct reports) or a wide span of control (with many direct reports)? The answer to this question depends on a number of factors, including frequency and type of interaction, the proximity of subordinates, the competence of both supervisor and subordinates, and the nature of the work being supervised. For example, you’d expect a much wider span of control in each individual department of a golf course than perhaps decisions being made from the top-down and the need for certain processes or procedures to be followed to achieve a specific organizational goal.

Delegating Authority

Given the tendency toward flatter organizations and wider spans of control, how do managers handle increased workloads? They must learn how to handle delegation—the process of entrusting work to subordinates. Unfortunately, many managers are reluctant to delegate. As a result, they not only overburden themselves with tasks that could be handled by others, but they also deny subordinates the opportunity to learn and develop new skills.

Responsibility and Authority

As the owner of a Golf Course, you’ll probably want to control every aspect of your business, especially during the start-up stage. But as the organization grows, you’ll have to assign responsibility for performing certain tasks to other people. You’ll also have to accept the fact that responsibility alone—the duty to perform a task—won’t be enough to get the job done. You’ll need to grant subordinates the authority they require to complete a task—that is, the power to make the necessary decisions. (And they’ll also need sufficient resources.) Ultimately, you’ll also hold your subordinates accountable for their performance.

Centralization and Decentralization

If and when your company expands, you’ll have to decide whether most decisions should still be made by individuals at the top or delegated to lower-level employees. The first option, in which most decision-making is concentrated at the top, is called centralization. The second option, which spreads decision-making throughout the organization, is called decentralization.

- Centralization has the advantage of consistency in decision-making. Since in a centralized model, key decisions are made by the same top managers, those decisions tend to be more uniform than if decisions were made by a variety of different people at lower levels in the organization. In most cases, decisions can also be made more quickly provided that top management does not try to control too many decisions. However, centralization has some important disadvantages. If top management makes virtually all key decisions, then lower-level managers will feel under-utilized and will not develop decision-making skills that would help them become promotable. An overly centralized model might also fail to consider information that only front-line employees have or might actually delay the decision-making process. Fortunately, many golf courses have a board of directors or member committee that help make democratic decisions by taking into consideration on how decisions will affect all areas of the operation.

- An overly decentralized decision model (similar to the club link example) has its risks as well. Imagine a case in which a company had adopted a geographically-based divisional structure and had greatly decentralized decision making. In order to expand its business, suppose one division decided to expand its territory into the geography of another division. If headquarters approval for such a move was not required, the divisions of the company might end up competing against each other, to the detriment of the organization as a whole. Companies that wish to maximize their potential must find the right balance between centralized and decentralized decision-making.

Key Terms

Top managers are responsible for the health and performance of the organization.

Middle managers are at the center of the management hierarchy: they report to top management and oversee the activities of first-line managers.

First-line managers supervise employees and coordinate their activities to make sure that the work performed throughout the company is consistent with the plans of both top and middle management.

Specialization: Organizing activities into clusters of related tasks that can be handled by certain individuals or groups.

Departmentalization: Grouping specialized jobs into meaningful units.

A functional organization groups together people who have comparable skills and perform similar tasks.

Product division means that a company is structured according to its product lines.

Division structure because it enables companies to better serve their various categories of customers.

Geographical division enables companies that operate in several locations to be responsive to customers at a local level.

Organization chart: A diagram delineating the interrelationships of positions within the organization.

Chain of Command: The authority relationships among people working at different levels of the organization.

Delegation: The process of entrusting work to subordinates.

Centralization: The first option, in which most decision-making is concentrated at the top.

Decentralization: The second option, which spreads decision-making throughout the organization.

Key Takeaways

- Managers coordinate the activities identified in the planning process among individuals, departments, or other units and allocate the resources needed to perform them.

- Typically, there are three levels of management: top managers, who are responsible for overall performance; middle managers, who report to top managers and oversee lower-level managers; and first-line managers, who supervise employees to make sure that work is performed correctly and on time.

- Management must develop an organizational structure, or arrangement of people within the organization, that will best achieve company goals.

- The process begins with specialization—dividing necessary tasks into jobs; the principle of grouping jobs into units is called departmentalization.

- Units are then grouped into an appropriate organizational structure. Functional organization groups people with comparable skills and tasks; divisional organization creates a structure composed of self-contained units based on product, customer, process, or geographical division. Forms of organizational division are often combined.

- An organization’s structure is represented in an organization chart—a diagram showing the interrelationships of its positions.

-

- This chart highlights the chain of command, or authority relationships among people working at different levels.

- It also shows the number of layers between the top and lowest managerial levels. An organization with few layers has a wide span of control, with each manager overseeing a large number of subordinates; with a narrow span of control, only a limited number of subordinates reports to each manager.