SECTION 8: PARTICIPANTS’ RECOMMENDATIONS

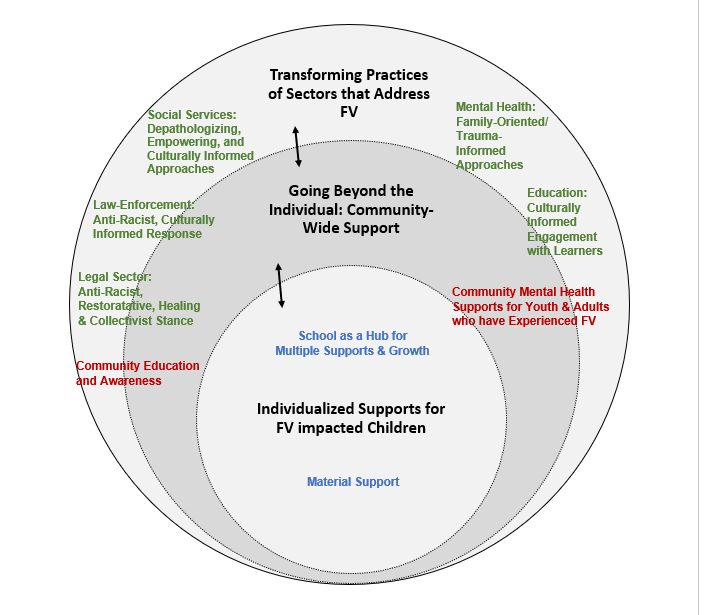

Below we provide a model for holistic, trauma and culturally informed services for racialized immigrant children living with FV. We have conceptualized the recommendations of participants under three themes: Individualized support for children impacted by FV; Going beyond the individual: Community-wide support; and Transforming the practices of sectors that deal with FV. Work at all levels, including transforming practices needs to happen simultaneously for sustainable impact on the lives of children experiencing FV. This holistic model is summarized in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Participants’ recommendations: Holistic, trauma-informed, culturally informed services for racialized immigrant children living with FV (Adapted from George et al., 2022, p. 9)

Individualized Supports for Children Impacted by Family Violence

Jasmine, Maria, Viktor, Sonia, Anita, and Sandiran discussed schools’ critical role in their lives. Some participants described the school as a place of refuge and stability amid chaos.

Viktor, Sonia, and Anita discussed the need for the school to be a safe space for children to discuss challenging issues. Sonia suggested creating opportunities for children to share what is going on in their lives and process their emotions without any dire consequences on their lives:

If you make it voluntary and anonymous so that nobody knows that they’re accessing this information, nobody knows that they’re using this information, maybe it’s online, maybe it’s like workbooks that they work through whatever it is. Maybe that could help, but it’s so tricky.

Maria also talked about the need for teachers to engage with children who are quiet or falling behind:

I think it’s more about acknowledging, too, because, for me, I was quiet. No one was even understanding. And in order to have the support, you have to see what’s happening and beyond . . . like in school systems. If a student is falling behind, at least question it, and then you will be able to have the right supports for that kid.

Maria and Jasmine also suggested counselling support for children in school. Sandiran discussed the importance of providing culturally and trauma-informed counselling support, which is discussed further in the Transforming the Practices of Sectors that Address Family Violence section. Jasmine discussed the importance of helping children with guilt and self-blame they might experience due to FV.

Viktor and Abi recommended recreational programs such as sports or art that facilitate channelling children’s energy or diverting their attention from experiences at home. Abi felt art would have helped her make friends, and Victor found sports helped him channel his aggression.

Along with managing the trauma of FV, Maya and Samantha shouldered the responsibility of running their homes without any skills. Based on their experience, they discussed the need for schools to provide academic and life skills to prepare children for such roles. Maya wished that someone had taught her about finances, how to clean the house, do laundry, and wash dishes, as these were things that she faced when her mother returned to work.

Participants also recommended school supports for children to develop academic skills and help with homework for children without support or with extraordinary responsibilities at home. Jasmine recommended that schools train children in effective communication, anger management, and self-care and encourage them to access supports when needed.

Based on Adriana’s experience, she recommended material support such as shelter and financial assistance for teenagers who may be forced to leave home to escape the toxic environment.

Going Beyond the Individual: Community-Wide Support

This theme looks at participants’ perspectives on going beyond providing support at the individual level to working at the community level, focusing on remedial and preventive aspects of addressing FV.

Participants recommended counselling and mental health supports for racialized immigrant youth where FV was not identified or occurred late in childhood.

Based on the multiple mental health challenges they experienced, Maria, Chiairo, Adriana, and Anita discussed the importance of community mental health support for youth and adults who have experienced FV. Based on her experience, Adriana talked about the significance of mental health support for children: “Definitely mental health support [for children], a method to express themselves as they would have an identity crisis on top of the abuse that they’re experiencing at home . . . and they have nowhere else to go.”

Unfortunately, none of the participants except Maria (who was in Guyana then) could access counselling support while in school, as OHIP does not cover it. They accessed it only while in the university, where free counselling is available for students. Sonia accessed counselling support privately as she was out of university then.

Sonia and Samantha discussed the importance of providing mental health support to adult men and women involved in FV. However, Sonia drew attention to the stigma of mental health in ethnic communities that might prevent individuals like her father from accessing counselling, even though they needed it.

The participants discussed the criticality of community education and awareness to address the stigma related to FV, make community members realize that FV is not a personal/familial but a social issue and encourage them to access community supports. It took Chiairo a long time to find the language to speak about FV and understand the patterns of abuse and control she was experiencing. Based on her experience, she suggested community-specific education on identifying FV and intervening when it happens.

Sonia lamented that her father, who needs mental health support, does not avail himself of counselling services because of the stigma of counselling in the community:

And I wish that maybe he saw that on . . . a billboard at the [place of worship] one day and was like, oh, this talks about how I can manage my anger, maybe I’ll . . . call them and do it. But there’s nothing . . . that’s also in [City in Ontario]. It’s nowhere else.

Maria added that in Canada, where immigrants come from a context without enough mental health support, educating immigrants and addressing the stigma of mental health before expecting them to access support is essential.

Transforming the Practices of Sectors that Address Family Violence

Moving from support at the individual and community levels, this section provides participants’ insights on how sectors such as healthcare, including mental health, education, social services, law enforcement, and the justice system could respond more appropriately in the context of racialized immigrant children experiencing FV. Participants made recommendations based on their struggles with the services provided by these sectors. This theme highlights the essential work that needs to be done to support people experiencing FV and take preventive action to address FV. The recommendations call on governments to increase resources for remedial and preventive work.

Mental health sector: Adopting family-oriented and trauma-informed approaches

Abi talked helplessly about the inappropriate mental health support her father, who suffers from war trauma and developed schizophrenia. She said, “My dad . . . had a language barrier, my sister or I have to translate at appointments, and just the healthcare that he receives, [the] medication . . . it’s not really . . . helping him deal with anything . . . it hasn’t resolved anything.” She felt more appropriate services could have helped her father recover and for them to function as a family.

Abi’s disappointment in her father’s current mental health treatment was echoed by her sibling, Sandiran, who felt that the Canadian healthcare system was too narrowly focused on the individual. They recommended a family-oriented, trauma-informed approach to addressing FV:

So, I think like, like a family approach to domestic violence, a family approach to abuse is so necessary . . . and I also expand that outward to . . . community approaches to healing . . . you know what does it mean when a war afflicted family, a war afflicted community is now in a region where they, they’re not, no longer in that war but that war remains in a lot of internalized ways and so what does it mean to provide proper community services that link, individual to family to community, especially in communities where that trust has been eroded because of the political, social tensions.

Abi also spoke of the importance of intervention to keep the family together while working with all members. This intervention should support all individuals caught in the violence with their best interests in mind and support them living as a unit rather than isolating family members from each other and eventually breaking the family apart.

Chiairo recommended making mental health supports affordable and accessible so that they could be widely accessed by children and youth when needed:

I think that if mental health care was just more widely available and potentially free or very low cost or subsidized, getting that support would probably be a lot more feasible, a lot earlier.. . . because you know therapy isn’t covered by OHIP . . . I’ve gotten most of my therapy through the schools that I’ve gone to and then … my partner was working at a place that had like health benefits … that is like … a privilege

Education sector: Offering culturally informed engagement with students

Sandiran discussed that racialized immigrant children may not display typical signs of abuse and suggested that teachers need to be able to have conversations with students about FV and identify a child living with FV, even if these children are not demonstrating disruptive behaviour or showing signs of abuse:

It could be a child who was like myself, my brother and my sister and many of the people I know. We are quiet children who go through our school systems, and the signs aren’t clear. To be able to recognize that, especially for model-minority communities, where we’re taught in collectivist cultures to be more quiet or keep to ourselves like the signs are not the same. We need . . . people in [the] educational sector . . . to ask different questions, to look in different ways.

Sandiran also recommended a bottom-up approach that taps into community expertise to develop services. This would mean including racialized immigrant communities in designing support for their children and vesting resources in their hands to implement this work. It also calls for transforming the current education sector by training teachers to be culturally informed and support racialized immigrant learners experiencing challenging circumstances in their homes.

Justice System: Embracing a restorative and holistic approach

The participants discussed the need for the legal sector to take a holistic approach. Based on their personal life experiences, their narratives reveal various factors that aggravated FV. They recommended a holistic approach to addressing FV and provide healing for all family members, implying a complete transformation in the functioning of the legal sector.

Sandiran shared their perspective on the violence in their home, the factors that aggravated the situation, and how it could be addressed using a restorative justice approach and with an understanding of collectivist worldviews.

Chiairo shared her perspectives on the discrimination against racialized children and men by the justice system and challenged it to change its approach:

I think . . . we need alternatives from the justice system that is punitive as systems that . . . take away children of colour . . . at exorbitantly disproportional rates. I think that there’s a lot of fear of those systems and a fear of interacting with them. . . . Violence is often cyclical, it’s often trauma-based, and I think a lot of other people who actually get support in those, those cycles of violence and are treated through less punitive measures are our white folks . . . mainly [White] Canadians and not, not men of colour.

Chiairo’s reflections highlight the disproportionate rate of racialized children taken away by the State (through CPS) and the criminalization of brown men, especially after 9/11. Chiairo points to the limitation of such a punitive approach without support for families that are trapped in it:

We need our Children’s Aid Services [CP] to be restructured . . . starting to look at forms of justice that are . . . restorative and transformative justice. So, a child’s aid service[CPS] that is rooted in that form of justice that acknowledges that violence towards someone is unacceptable. It means healing those relationships. So, I’m thinking about very large principles . . . premised on this idea of restorative practices, and also collectivists practices.

Law enforcement sector: Adopting a culturally informed response

The participants recommended a de-escalation versus arrest approach by the police, listening and respecting the parties involved, and a more culturally informed approach to address most FV cases among racialized immigrant families. Participants called for a reassessment of the law enforcement sector to empower police to better assess risk to family members, to listen and respect the parties involved, and to use a culturally informed and victim-centered approach to address most FV cases among racialized immigrant families.

Based on the experience Sonia’s mother had with law enforcement officers, Sonia shared an approach that would help racialized immigrant women:

Yeah, I don’t know if this is relevant, but the police officers that came to my home were white. I don’t know if they were brown, would it have been different, like would they have been able to talk to my dad in Punjabi and calm him down? Would that have worked? I don’t know. He didn’t have to get arrested that day. It was the arrest that sparked all this. . . . My mom . . . just wanted the situation to de-escalate.

Social service sector: Embracing culturally appropriate approaches that do not stigmatize and that facilitate freedom from oppression

Chiairo and Samantha reflected on alternative ways of supporting racialized immigrant families. Chiairo discussed the need for culturally informed support to preserve the family and establish a healthier, healing relationship between members. She felt that “an alternative system of care and practitioners within those systems who have a greater understanding of some of the social and cultural dynamics that might be at play” would be helpful. She also suggested that resources and supports from outside the community would be particularly beneficial to persons from small towns to avoid gossip. She also shared the need for societal and religious support for women who do not want to leave their abusive spouses but have healthier relationships with them

I don’t think my mom would have ever left [my stepfather]. So [if] there was a way that I could engage somebody else to support . . . help them have a healthier relationship, and that can be like, through our religious community, or through our broader social net.

Similarly, Samantha talked about the importance of de-pathologizing families requiring support and transforming social services from a surveillance-based institution to an empathetic and emancipatory one:

More training for some of the staff and the institutions who are coming into contact with the kids. Just to give me a bit more empathy on what’s going on or more understanding because I can imagine honestly like if I don’t come from the background if I come from a very stable, different background . . . I would react the same way they did, right. But I think, for them to best support those people . . . it might benefit them to have more information and training . . . more knowledge and empathy. . . . Even . . . Ontario Works, like, you know, I think it’s harder for them, but you know I imagined they meet many people, you know if you don’t have your things together and struggling, I think half the time it’s not because you’re lazy, it’s because there’s a lot more going on right. And I think having that approach . . . maybe more empathetic approach, or more empowering approach at every step of the way.

This section brings forward the voices of participants who recommended fundamental transformative changes in various sectors of our society. These recommendations are invaluable as they are grounded in the personal life experiences of participants and, hence, offer us immense insights into responding to FV in racialized immigrant communities. These voices call for a paradigm shift that acknowledges children who have experienced FV as valuable stakeholders and experts who deserve to be heard while deciding on family law matters that affect them profoundly.