SECTION 6: MAJOR FINDINGS

The key findings that emerge from this study are presented as the following themes: Direct and indirect experiences of FV, Roles played by participants during violent incidents, Differential experience, engagement and role of participants’ siblings, Accessing supports during FV, and The impact of FV on children.

Direct and Indirect Experiences of Family Violence

We use the terms direct and indirect to describe different types of violence experienced by participants. Direct violence connotes violence that participants were subjected to in their childhood, and indirect violence connotes participants witnessing violence directed toward their mothers. The findings revealed that while some participants experienced direct violence from either or both parents, others experienced indirect violence, their mothers being the target of direct violence.

Participants experienced many forms of direct violence: verbal, physical, psychological, sexual, and religious. The following excerpts describe acts of violence participants experienced and their impact on them.

Adriana recounted how acts of direct violence, in the form of verbal abuse, emerged:

It would happen mainly when there [was] something . . . I have done something that they might not have approved of, and thus they would react to my actions with, you know, physically beating me and then my father would go on to blame my mother for my actions, and thus they would start an argument because of me. . . . I come from a very conservative family . . . and they would use a lot of things like “you will burn in hell” and that sort of thing to sort of scare me into, you know, obeying what they believed was acceptable into their culture; everything in my life was controlled.

Adriana experienced verbal abuse when she acted in ways her parents felt were contrary to their religion. Her mother was the source of much of the verbal abuse:

She said that I was the child of the devil and that my head was being controlled with demons, and that would be used a lot . . . beating me and my mother brutalizing me emotionally with words such as, you know, “I hope you burn in hell.” It’s very important to understand that in that family’s cultural set[ting], it’s like the use of fear technique was very much used in things like, “I hope you burn in hell, I don’t understand why God even created you; you are a disgrace to us” . . . in this scenario, it’s mostly the use of religion, you know, the comparison between the disobedient child and demons, and saying that demons are controlling my head and that sort of thing.

Adriana’s father stalked her and even controlled her while she was living away from home, attending school:

I was constantly [terrified that my father would find me]. . . . There was one incident that . . . happened. . . . I was getting off the school bus, and I was walking home, and then obviously he had found out from somewhere that I was taking this school bus. . . . Anyways he was hiding in a bush. I did not see him, I put on my headphones, and I was walking home, and then all of a sudden, I start hearing my friend calling my name and shouting, and then I take off my headphones, and I look back and I [saw] my dad running towards me and my friend [was] running after him trying to . . . stop him. And then I just start[ed] running, I [froze] for a second, I think, because I just panic[ed], and then he catches up to me, and then he starts holding me and pulling me and saying let’s go home. . . . They took away my phone, they took away my case, they took away everything, and they took away my passport.

The psychological violence transitioned into physical violence on another occasion when both parents attacked Adriana in her new home:

There was one time in December 2018 . . . I opened the door [to my room] . . . and [my parents] grabbed me, and then they start[ed] . . . dragging me from the seventh floor to the first floor. I tried to run, but I couldn’t. I was wearing a necklace . . . around my neck, so my mother starts pulling the necklace around my neck, almost choked me, and I realized, you know what, they’re not gonna let me go. I’m not gonna be able to escape because two of them are pulling me and dragging me, so I just didn’t move, I just played dead, you know, and I started screaming, I started screaming, “Help, help, call the police” and my neighbours were obviously all very, you know shocked . . . my neighbours gathered around us, you know Chinese people, they gathered around us, and obviously none of them understood, you know, the swearing was in Arabic, you know, so none of them understood what was going on so I was always screaming in Chinese, you know, “Call the police, call the police,” and one of them finally, I’ll never forget this, one of them, you know, held my father’s arm as he was, you know, hitting me, and told him, you know, “You can’t do this.” . . . And for a while, for about a month after that or two weeks, I was living at different people’s houses because I was too scared to go back to my place. I would eventually, after a month, find a new place to live, and I would go back and sleep at night to my old place just in case anyone was watching the place. So I would pack all my things, empty the place, and return the keys to the landlord, and go to [a] new place.

Adriana’s narrative provides a glimpse into the severe physical, emotional, verbal, and religious abuse and coercive control she experienced from her parents. The father exercised his influence and power in many ways to control and abuse Adriana, and her mother colluded with him. Her mother desperately tried to convince Adriana to change her path, citing religious teachings and expressing fear of the eventual damnation of Adriana’s eternal soul.

Maya shared her experiences of both direct and indirect violence:

They [parents] came to Canada when they were like teenagers . . . that’s how they met, then they got together so for them it was like a choice to get married, rather than they were compelled to. My mom’s family didn’t want her to get married, and my dad’s family didn’t want him to get married . . . there were like multiple issues. So mostly, it was caste issues, and then it was financial issues. . . . Both of them graduated high school, but neither of them went to college or post-secondary . . . there were still arguments because of things like caste. . . . My dad would hit my mom, right, so hitting, using like whatever he had in his hands, kicking her. . . . I remember seeing him jump on her . . . so I stopped him, and I pushed him off . . . sometimes, like when there was a fight, he would be escorted off by officers. And, or, like, I think only once he actually got arrested, but then other times he would just leave.

Maya’s excerpt reveals several factors contributing to a strained relationship between her parents. First, they were from different castes. Second, the excerpt highlights the struggle of new immigrants caught between attaining a higher level of education and earning income for survival.

In addition to witnessing violence, Maya talked about her experience of being abused by her mother. Recalling her situation, she said,

I didn’t like my mom, either, growing up, I guess, because she would say emotionally manipulative things like, Oh, “if I didn’t have you guys, and you know I’d be free.” All this stuff, which I remember vividly, and she still says stuff like that nowadays. . . whatever abuse she got from my dad, she would just throw it back at us. So she was physically and emotionally abusive, and then it just got worse in high school . . . because that’s when the gambling happened . . . it made it worse because she would leave me alone to watch my siblings, so I had to like, leave school; I couldn’t hang out with friends or anything, or I couldn’t do extracurriculars. . . . I don’t remember there being a key . . . so I would have to go through the window first . . . then open the door so then when my siblings came home . . . I had to learn how to start cooking [and] things like laundry and cleaning the house so it looks proper.

The above excerpt highlights the physical and emotional abuse Maya experienced at the hands of her mother, the downloading of the responsibility of looking after her siblings and its impact on her academics. It also reveals the pattern of abuse as a transfer of abuse.

Chiairo watched her stepfather abuse her mother physically and emotionally. In addition, his controlling and abusive behaviour also jeopardized Chiairo’s safety:

I think probably the most obvious way early on to notice was, was that he was very controlling. . . . He didn’t like when my, my mom, you know, left the house without him, knowing where and who she was with, and didn’t want her to drive. . . . At one point, he really got upset when, when she wanted to go anywhere by herself, or when my mom spent time with friends, he would get upset . . . a lot of isolating behaviour. . . . When he was upset, he would act in ways that sometimes jeopardized our lives . . . he would drive, really, really dangerously. About a decade into their relationship . . . my mom finally told me that he sometimes hit her and grabbed [her]. My elder sister once witnessed him dragging her out of a room.

This excerpt illustrates aspects of Chiairo’s stepfather’s coercive and emotional control by isolating her mother and family members from their networks, his physical abuse, and his reckless behaviour to instill fear in family members. Chiairo’s mother kept the physical abuse a secret for a long time until Chiairo was older.

In addition to the impact of interpersonal violence, Chiairo’s story offers a glimpse of how racism played a role in family violence:

I think part of the reason that I was so adamant about no one knowing that he [stepfather] existed, let alone what was happening . . . my mom’s husband . . . was White . . . and I think race also played . . . a role . . . in that relationship of control and violence. He did say a number of racist things throughout our lives . . . comments about . . . the way my grandparents spoke, or comments about family members, and like the observance of certain cultural traditions, or comments [about] my mom’s friends or relationships within the community. . . . I think part of it was born out of like this feeling of exclusion . . . he sensed a sense of community and connection there, he wanted to isolate her from it, and so he was like incredibly critical of a number of people in the community and some of that was under-handed comments about people’s . . . education . . . and intelligence.

Viktor is the eldest of three siblings. His mother escaped from their home with three children when he was very young. As a child, Viktor witnessed verbal and physical violence directed toward his mother and sometimes toward himself and his siblings. Talking about the violence, Viktor said,

I feel that [FV] always causes a sense of unease because you never know when the next event is gonna blow up. You feel like it’s sort of like a time bomb or like it’s only a matter of fact, the next incident occurs. . . . I forget exactly when we actually left, like the exact year, but [I remember the violence] . . . it would be arguments and physical. It was not uncommon for him to get physical at all, be it on either my mother or any of me and my siblings. . . . Those arguments and fights and all that stuff have stemmed from other things that weren’t really related to us usually, but it did spread to us as well, and as a child, it did change our sort of mindset to be like I don’t want to get punished.

Viktor’s experience captures a child’s emotions and fears when navigating an abusive environment. He talked about his feelings of uncertainty, of always feeling uneasy and on edge, of never really knowing when the next incident would occur. Viktor’s story draws attention to the harm caused to children who live in constant fear in an abusive home; it highlights how fear and abuse rob children of their childhood.

Jasmine recounted that while growing up, there were often verbal arguments between her parents. Their frustration and anger were not only directed toward each other but also at Jasmine:

Once we came to Canada, we were in close quarters, I also have a younger brother, and we lived in a small apartment, the four of us together, and I remember that’s when it became extremely difficult because I would see them fighting and everything . . . mostly petty arguments. Sometimes it would get very loud. I would say verbally violent. . . . I remember before we came to Canada . . . I remember my dad’s side of the family. They were very controlling of my mother. . . . My father also had a habit of trying to buy our love, you know. If he would really attack my character or make me feel terrible, I remember one day, both my mom and my dad were scolding me so much about my grades that I was literally covering my face in a corner in the fetal position, just crying, asking them to stop like I was begging them to just stop.

Many of the participants in this study witnessed severe violence between their parents. In every case, the father directed this violence toward the mother. Two participants, Abi and Sandiran, interviewed individually, are siblings, with Abi three years older. After having a very rocky relationship while growing up, they have realized the reason and are now rebuilding it. Interestingly, even though they witnessed the same violence, their perspectives differ. As indicated in the excerpt below, while Abi shares her mother’s response to the abuse by her husband, in Sandiran’s narrative, this information is missing. Abi recounts witnessing the violence:

My father has an illness . . . because of his illness, he kind of . . . took out his [fears] . . . on my mom. And my mom didn’t have anybody. . . . She was also angry at my father for not doing his role as a husband and father, so there was tension in that sense, so my father was angry with my mother for something, and my mother was angry with my father. . . . I think what happened was upon arriving in Canada . . . his illness either got worse or was to the point where it was identifiable. I think in Sri Lanka, maybe he already had the illness, but he was able to suppress it, and he was able to go on being pretty functional. But upon arriving in Canada, and I guess with the different stressors, he ended up, he ended up not doing as well.

Abi’s experience shows how her father’s battle with a mental illness strained his relationship with his wife and children. Abi’s parents’ relationship seems stressful because her father did not fulfill his family role. Abi speculated that her father’s illness became identifiable upon their arrival and settlement in Canada as different stressors were introduced in his life. Abi hinted at the settlement challenges experienced by racialized immigrants in this country, which her father could not manage, exacerbating his mental illness.

While Abi shed light on the causes of FV, Sandiran provided a graphic picture of the nature of the violence in their home:

My dad has paranoid schizophrenia . . . because of the traumas he’d gone through during the war and how that affected his life. That’s why he would go to beat my mother, and so we would have to kind of, like, pull him out. Like, harm him in some ways so that he could stop harming my mother. . . . My dad also has another co-morbidity that’s related to his schizophrenia, and he was at least a very, very heavy alcoholic, and we took his alcohol away from him because we had no other option. He also became violent because he didn’t have access to money. . . . [My mom] would sleep in our bedroom because at night my dad would come in to beat her . . . taking my mom’s head and slamming it. . . . I’m sure I had a heightened sense of stress, and I think I’m bringing in my medical background here and a heightened sense of a heightened level of cortisol . . . it was just normalized over the course of our lives.

The above excerpts highlight the importance of support for people who have experienced war trauma and new immigrants who have settled in Canada. Sandiran’s reference to the normalization of violence, when it occurred regularly at home, signals the importance of preventive services for immigrants from war-affected regions. Sandiran’s description also highlights the significance of taking proactive steps to minimize and respond to the physical violence of her father.

Maria shared her experience witnessing physical, verbal, and financial abuse towards her mother while growing up. Maria was very aware that her father was violent towards her mother:

He used to beat her [or] hit her. . . . For the verbal abuse, he used a lot of bad words—cursing, yelling, degrading who she was as a woman. Financially, he was never a good provider . . . and if it wasn’t for her having a place [that she rented], she wouldn’t have had an income.

Maria’s father’s violence had a negative impact on multiple aspects of her life. She witnessed her father degrading and disrespecting her mother and abusing her verbally, physically, and financially. Like other participants’ fathers, Maria’s father left it to Maria’s mother to provide for the family.

Samantha’s mother escaped from Pakistan with Samantha as an infant and sought refuge in Ontario. However, the mother returned to Pakistan when Samantha was five years old and escaped again three years later when their domestic situation did not improve. Samantha recollected witnessing violence while they were in Pakistan:

My mother, she tried to again and again to go back and live with my father [because of financial and cultural pressures], but she was unable to . . . establish [a] relationship with him . . . or the brief amount of time that we lived with my father, there was always a lot of financial, physical, emotional abuse. . . . The yelling and fighting would start in the morning . . . because my father was very short-tempered. . . . I think the physical [abuse] . . . when I would see it happen was difficult. . . . My parents only lived together . . . for three years in total . . . [and] have four children together . . . All of the domestic violence and the custodial issues took place in [Pakistan], but there were a lot of implications that happened in Canada. . . . I lived in [Pakistan] till I was about four or five, and then I came to Canada with my mother and all my siblings were left behind in Pakistan because of the custody issue. . . . To this day, all three of my siblings still live in4 [Pakistan], and I grew up here [in Canada] . . . we don’t really know each other or anything. They have no relationship with my mother because they’ve always been taught to be against her. . . . It’s not their fault; it’s just what they’ve been taught over the years . . . it’s a very fractured dynamic in our family, resulting from the domestic abuse, the very controlling nature [of] my father.

The “fractured dynamic” Samantha described is present in several participants’ stories wherein FV has impacted relationships between family members – parents and children and also among children. Samantha’s story highlights the long-term impact of abuse and separation from her children on her mother’s mental health, who developed schizophrenia later in life. Samantha has played a caretaker role for her mother, while her siblings live with the misunderstanding that their mother abandoned them. From Samantha’s point of view, her mother could not bring her siblings to Canada because of custody issues and immigration policies and procedures.

Samantha also suggests that the factors that pushed her mother to reunite with her husband after deciding to leave were financial and cultural. This points to the stigma and isolation experienced by divorced/separated women in certain cultures. 3

Sonia described witnessing verbal, emotional, and physical violence directed toward her mother by her father and his family. She recalled the relationship between her parents, who immigrated from India, as follows:

My parents have always not really gotten along. It was an arranged marriage, so it wasn’t by choice; they didn’t really know each other. And since day one, my mom has always had conflicts or tensions with my dad’s side of the family. When they immigrated to Canada, those tensions . . . just got worse. I was around 10 when I saw a physical event happen between them . . . my dad pushed my mom down the stairs . . . she had rug burns, all the way down her arms, her forearms. . . . When they came to this country, they didn’t really have anything to get good jobs with, and my dad started off as like a cab driver and then made his way into trucking, so he’s a truck driver now, and my mom, she’s primarily worked in like factories her entire life. . . . And I think that I’m sure [finances] played a factor.

Although her parents did not explicitly say so, Sonia knew that her parents had conflicts from her childhood. Like Samantha, Sonia stated that her mother faced emotional abuse from her father’s family. Similar to Maya’s situation, Sonia’s case also highlights how financial stress increased tensions at home that contributed to transforming a home into a violent space.

Anita witnessed verbal arguments between her parents that often revolved around their daughters’ futures. Her parents lived in a Middle Eastern country and decided to immigrate to Canada. Anita described the situation as follows:

The fights I’ve seen were more about our future, about moving, about giving us a better life. My mom wanted to come here because we still lived in [a Middle Eastern country], and my mom saw that there’s no future for [her daughters]. My dad did not like the Western culture, so [he disagreed]. [Friends and relatives] would tell both of my parents that Western culture isn’t good, your daughters are, in fact, not kids, your daughters, and I’m emphasizing daughters because there is always a gender difference. Their fights would end up [with them] not talking to each other for a few days or even weeks.

Anita’s experiences reveal a cultural factor that can lead to tension in immigrant families—the fear of daughters assimilating into western culture. The tension between Anita’s parents reflects gender-based discrimination in many cultures, where girls are expected to carry the burden of cultural preservation. Anita’s mother fought to get her daughters out of a constraining environment to an environment that provided more opportunities for them. Her mother sought help from her sister, who lived in Toronto and supported their immigration plan. The father’s side of the family was resistant to the idea of immigration and influenced the father negatively. The resulting FV in Anita’s family manifests the dynamics in many family-oriented cultures where extended family members play an essential role in decision-making for other members.

Jay described the violence between his parents that was both physical and emotional. The violence was physical, as the father threw and broke items around the house, and these actions had an emotional impact on Jay:

A lot of things broke up and like, you know, furniture, glasses, tumblers . . . it was just over some small little funny things between my mom and dad, things that kind of annoyed my mom like she’ll kind of like just hold it in and then like once or twice, she’ll say certain things. . . . For me, it was just more like things that I saw; there was no actual harm that was actually done to me like, like physical harm or anything. . . . I just saw my dad kind of get like, you know, roughed up or not roughed up like you know, loud and stuff, and things might break but nothing where anything comes into harm, so everything like no. . . .[until] I saw harm done to my mom. . . . I kind of noticed something, witnessed something, and then I told my dad, I’m like, “Listen, either you call, or I’m going to call [the police].”

Jay’s experience provides insight into the reality of a home where abuse is normalized; it is not spoken about. In such contexts, it is challenging to act until the situation worsens. Jay’s action demonstrates his agency in standing up against such normalization of violence at a young age.

This section looked at the direct and indirect FV experienced by the participants. Their experiences uncovered the personal, cultural, religious, and systemic factors that converge to complicate FV for racialized immigrant families. The following section provides insight into the roles the participants played as children at the time of FV.

Roles Played by Participants During Violent Incidents

During the interviews, participants were asked to speak about their role when tension escalated between their parents. The interviews revealed that participants felt compelled to take on demanding roles often at a young age: Protector and provider, Peacemaker, and Challenger. The data revealed that some participants played multiple roles fluidly at different times, and their roles varied depending on the context and their age. However, the analysis below focuses only on the dominant role(s) the participants identified they had played within their families.

Protector and provider

Maya, the eldest child in her family, found herself having to act as a protector of her siblings and be their provider and caregiver while her mother was absent because of her gambling problem:

I’m the older sibling, so I had to take on a protector role at a young age. . . . I had to worry about whether my siblings [were] home and whether they [could] get into the house because [my mother] . . . said she’d leave a key, but I don’t remember there being a key . . . so I would have to go through the window first . . . then open the door so then when my siblings came home. . . . I had to learn how to start cooking.

While Maya automatically took on the role of protecting her siblings, Viktor was conscious of the need to fill the same role to alleviate his mother’s responsibilities but was reluctant to take it on:

I actually kind of [had] to act . . . like a parent to the other two kids . . . and well, I [didn’t] really feel like I [had] a choice in the matter. I . . . saw . . . how my mother had to take on three of us to provide for us but to raise us as well. . . . Even if it’s something as simple as just taking my sister to work, that makes my mom’s life easier.

Interestingly, Maya and Viktor were subtly pushed into taking this role at a young age when they were least prepared for it.

Some participants were forced to intervene physically to protect their mother from their father’s abuse. Sandiran spoke about their and Abi’s collective efforts:

My sister and I, sometimes we would put our bed in front of the door . . . so we would know when he would come in. Sometimes, my mom would sleep right next to us . . . once we woke up to him like beating on her, and so we would have to get him and . . . pull him out.

Samantha shared how she navigated playing a similar role in Pakistan and Canada:

There was always like a severe fear of my father growing up . . . because I could tell he controlled everything . . . like every day you know he would come home around 7 pm . . . we all have to be quiet and be very careful, you know, like a walk on eggshells around him, because, you know he could be very nice, but it was just like a matter of seconds when his temper went off, and then he would like lose it completely right, so it was a lot of fear. . . . I would try to . . . intervene, to stop him, but he would continue. . . . I was . . . very protective [of] my mother, and especially because [of] her mental health, I could tell from . . . a very young age [that there were] issues. We came back [to Canada] when I was ten [and] were living in . . . a shelter as well, and we stayed there for a few months. My mother . . . she’s a very . . . affectionate, loving person and . . . I’ve seen her repeatedly in very bad situations with my father and her own family. . . . I feel protective of her now, trying to help her be in a better place and . . . the impact of all that on me is that a lot of times, one, you build a lot of patience, so you have severe patience, two is like learning how to deal with . . . continuous setbacks or problems . . . and it’s exhausting at times but . . . you get better at dealing with like little crises, over and over again.

Samantha’s narrative highlights the complicated role she played in different situations. Even though she intended to protect her mother, she could not do much to protect her mother due to her father’s fear. However, she became her sole caregiver and protector through her challenging physical and mental health problems, such as liver failure and schizophrenia.

These excerpts reveal the incredible responsibilities Maya, Viktor, Samantha, and Sandiran shouldered at a young age, whether willingly or not; they accepted their expected roles. As children, they were called upon to not only deal with the impact of violence on themselves but to think beyond themselves and protect their siblings and mothers.

Peacekeeper

Apart from taking care of her mother and her brother, Sonia found herself having to be a peacekeeper in her home:

I got involved to de-escalate that situation for sure. I’ve never been hit or anything like that. That’s never happened, but like I’ve definitely been like the peacekeeper if that makes sense. . . . I have no problem yelling at my dad. . . whether I’m getting mad at her for bringing up something that she shouldn’t be bringing up and causing a fight about something that’s irrelevant, whether I’m trying to de-escalate him . . . I’m always the person that de-escalates. . . . And as I’ve gotten older, like I do everything for my parents. Anything financial-related, I’m now the “go-to.” I’ve always filled out my brother’s school forms, I’ve always, I’ve gone to my brother’s parent and teacher conferences because my parents don’t understand what’s being said properly, and so I’ve always taken care of my mom, and that responsibility has pretty much exponentially grown as I’ve gotten older.

Challenger

Participants shared the way they challenged their abusive parent/s either overtly or covertly.

Jay overtly challenged his father’s decision not to seek medical help after he hit his wife and she was injured. As a child, Jay was not sure of the severity of the wound and requested that his father call 911. His father refused to do so, so Jay called 911 based on his concern for his mother’s safety. According to Jay, his intervention was successful as it made his father cautious about not repeating such behaviour in the future.

Maria remembered being very young and screaming at her father to stop the abuse. She would “scream and tell them, stop. . . . I was young; I was like 5-6-7. . . . So when I see her screaming, or I see those kinds of stuff, all I would cry and scream and tell him, stop, like you know, beg.

Chiairo’s tactic of challenging looks different. She used the covert strategy of convincing her mother to leave her abusive husband.

Adriana shared her story of overtly challenging her parents’ expectations of wearing hijab as per their religious norm:

When I leave the house, I would be dressed as my mother wished, you know, a long shirt like down to my knees, and then hijab, and then once I leave, I would have like a change of clothes in my backpack. . . . I would change my clothes on the staircase. . . . Also, other times I would wait till I go to the subway and then change my clothes in the subway bathroom and then before coming home, I would do the same thing and change back into like clothes. So, it always felt like Cinderella, you know.

Most excerpts in this section demonstrate participants’ agency in playing different roles and accepting new ones per the situation’s demands.

Differential Experiences, Engagement, and the Role of Participants’ Siblings

It is crucial to emphasize that the participants acknowledged that their experiences and roles differed vastly from those of their siblings. The intersectional analysis below presents siblings’ engagement and roles based on their age and gender intersections.

Intersections of gender and age

Sandiran is the youngest child in their family. However, they made significant efforts to protect their mother and navigate the violence that was going on at home. Talking about their experience, they shared that their experience of FV at home differed from their older brother’s and sister Abi’s experiences:

Throughout the course of my life, my brother was always the one to take more action because he was a male, male child and he was also the oldest. I think, once, I was getting older, I had more sort of control to be able to yell at my dad and to essentially threaten him if we ever heard him threaten my mom if you ever sort of raised a hand to try to hit her.

Sandiran continued:

My mum was very strict with my brother and my sister when they were growing up, but as I was the last child in the family . . . I had a lot more privileges, and a . . . lot less of this affected me compared to how it affected my older two siblings who had to take on like [the] role of the father or this mother-role when my parents couldn’t, or were there. . . . And he taught me, and he was a really good big brother like even when I got bullied in school, he would come in and he would yell at the kid who bullied me. . . . I have a lot of respect for just what he went through because I don’t know what I would have done as a first-child, as a first-male, having so much of that pressure on him.

Sandiran’s experience sheds light on how siblings experience the same situation differently based on age and gender. Sandiran’s brother, the only male child in the household, had to take on much more responsibility because of his gender. Sandiran was sheltered and protected as the youngest in the family but took more responsibility as they got older.

Viktor is the eldest of three siblings; his parents separated when he was five. Because of this, he felt he had to help his mother and take on the responsibility of looking after his younger siblings, even if it was as simple as taking his sister to work, to make his mother’s life “easier.” Viktor also felt that sometimes his mother relied on him to support her. This family dynamic made him a critical link between his siblings and their mother.

The excerpts also highlight that gender and age played a significant role in expecting the oldest male child to take on the responsibility and fill in the void created by FV. The relationship between the first child and the parent seems much more potent based on how the child supports and stands with the parents during the separation phase of a divorce. However, in the case of some participants, the families did not adhere to gender and age-based role expectations. The discussion below provides insight into the role expectations of some participants.

Looking beyond intersectional analysis

Sonia’s and Anita’s reflections challenge the gendered and age-based intersectional analysis provided above.

Sonia, the eldest of two siblings, stated that her younger brother does not engage with what happens at home. Even though he is expected to take on responsibility as a male child, he has not taken any, leaving Sonia to manage.

Anita, the middle child of three sisters, reflected on her situation. She and her sister did not try to control the violence as children. Her elder sister lives on campus, but Anita lives at home. She has taken on the responsibility of collecting her younger sister (who is 11 years younger than her) from school. Being in a university, Anita has to navigate the stress of managing her classes and arriving at her sister’s school in time to take her home. As the middle child, she finds herself trapped by having to meet many of her parents’ expectations.

Accessing Supports During Family Violence

This section shares participants’ perspectives on accessing the services of social institutions such as the Child Protection Services (CPS), known as the Children’s Aid Society (CAS), teachers, doctors, law enforcement officers, and counselling services. We discovered that many participants had accessed few or no institutional supports and that most had maintained secrecy about the violence they were experiencing at home.

Child Protection Services (CPS): Fear and secrecy about violence

Findings revealed that a few participants kept the FV a secret because of fear of CPS. According to Abi, keeping the violence a secret impacted her relationship with people outside the family.

It was very important that we kept my dad’s illness and everything that happened at home very private. So I know that I never, like in my experience, I never got close to anyone until maybe the past, like until maybe I hit age 20.

Sandiran confirmed Abi’s perspective on the need for secrecy:

Over the course of our childhood, at least, my mum was very adamant on teaching my brother and my sister, and me to not utter a word about what was happening at home to anyone. And I’m, you know, the more I grow up, the more I’m so thankful that she did that because I think we would have ended up in foster care. So, I think she knew exactly what she was doing.

Chiairo knew that there was a negative perception of racialized immigrants in society and did not feel comfortable talking about her abuse to counsellors and other professionals for this reason:

I probably would not have talked to a counsellor about it before . . . at an earlier point in my life. I know CAS would have been called on my family . . . and I think that’s a traumatic experience, and I think that especially the way it’s wielded against immigrant families and families of colour, especially in like small, mostly white communities, which is, it’s a community where I grew up. Yeah, I think that that is, is traumatic, and often doesn’t help. . . . I’m not an immigrant, I’m the child of immigrants, but I do identify quite strongly . . . with my community. I think that the way immigrant communities are treated within the justice system and . . . social work as well . . . I think often those systems that other people might see as people who can help, are people who might disrupt our lives, or harm us. . . . In my childhood, CAS [CPS] was called on my mother; it’s because, like we did karate. At one point, my sister got a bruise from karate, and somebody thought that my mother did that. And I think a huge part of that was because of my mom‘s identity . . . that people think that . . . [South Asian] people are . . . violent against their children, and those types of stereotypes. . . . When you grow up as one of the few families of colour . . . in a white community, I think that there’s an added layer that like you’re being watched and judged. . . . I have had a number of therapists and care practitioners. I think only one of those people has ever been a person of colour. . . . The advice that a therapist gave most of the times like didn’t always feel very relevant or appropriate.

Maya compartmentalized her school and home life. While she saw school as a place of escape from the realities of home, she also knew that it was not safe from the point of view of CPS. So, she was cautious and said,

School is a place where I can like to get away from my parents. That’s why I didn’t feel the need. Also, I knew that if I told them something, they might call CAS, and I already had that happening anyway, so then there was no point.

Because of her mother’s mental health, Samantha had to access services from several institutions over the years. She recalled her numerous interactions with CPS, Ontario Works (OW), Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), and Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP). Talking about her experience with CPS, Samantha said,

Unfortunately, from a young age, we had a lot of involvement with CAS . . . for example, you know my mom, sometimes she would say if you don’t want to go to school, you don’t need to go to school. . . . The school called CAS because they’re like she’s just not coming to school . . . and that gave a fear in my head of like being taken away from her. . . . So, I would be very careful to not speak out at all. . . . I was just so fearful of this, like if I’m not with her, then I am with my dad. When I was in grade eight . . . she was evaluated by a family doctor. . . . They figured out it was schizophrenia, and then she was hospitalized for about three months. . . . My mum’s brother, who lives in the US . . . he came and stayed with me for a little bit [of] time. . . . It was a difficult time with CAS . . . because they said that if I was not with him, I think I would have to go to a foster family. . . . This one time, the social worker was to just actually come by for visits, and so he literally, like that night, he booked a flight from the US to be available for the visit.

Participants’ reflections reveal an overwhelming fear and apprehension of being surveilled and judged by CPS. Grounded in Eurocentric practices that look down on collectivist and family-oriented values, CPS can end up separating children from their parents; hence, racialized immigrant families do not fit the mould of CPS and its services.

School: From a place of guidance and inspiration to erasure of experience

Sandiran, Chiairo, Samantha, and Maria shared their experiences with the school and teachers.

Sandiran’s apprehension about the response of CPS also carried over to schooling:

I didn’t talk about this with teachers because I went to an elementary school, a public school that was located in the richest neighbourhood in Montreal, whereas I and some of my peers were living in one of the most racialized low-income neighbourhoods in Montreal . . . and one of the best indications to me was when my teacher would ask me to tell the class . . . every year where I went [for vacation] . . . it would be go ask your, go ask your parents for help on this. I was like, I would remember, I remember just laughing and thinking to myself, well, these people don’t have any idea. . . . And I guess during those actual times I . . . would just need to put on like a smile and then go into school and do the things that I needed to do. . . . In high school, it was the same thing, I went to high school where it was more students from different backgrounds, but there as well there was never a time where I felt like any teacher had proven themselves to be trustworthy.

However, Samantha, Maria, and Adriana had different experiences with their teachers. While Samantha’s teachers complied with the Duty to Report procedure that leads to CPS involvement, Samantha also commented positively about the school and teachers:

Over the years, my teachers always could tell that things are off when my mom would show up at odd hours at school like it was a lot of eccentric behaviour. So, the school could tell there were issues going on . . . they were kind of empathetic . . . they did a good job of dealing with it. I think my interactions, like I’m still good friends with that one teacher for many, many years later because we lived in the same community.

While Maria kept the violence in her family a secret from her teachers in Guyana, her school eventually found out what was happening, which made her feel ashamed. This is indicative of the stigma associated with FV. Adriana talked about the tremendous support she received from her teachers in China. Her teachers were observant and noticed that Adriana was experiencing trouble in her home because of her subdued nature and artwork. Adriana felt comfortable talking about her abuse to one particular teacher. Though the teacher was on the safeguarding team at school and empathized with her, Adriana felt there was little the teacher could do.

Adrianna shared a story of what happened to her in the year 2018 on the last day of school before Christmas break. Adrianna’s parents stormed her home and dragged her down the stairs. One of the neighbours called the police at Adriana’s request. When the police refused to support Adriana, she reached out to her teacher:

I had my school laptop in my backpack. That’s how I was able to link it to the police station’s Wi-Fi. And, you know, I sent out SOS emails to everyone in my contact list, and luckily, one of my teachers checked her email before she boarded on the plane. Then she made a few calls, and then one of the administrators, you know, workers, you know, she came with her husband, late at night and picked me up. . . . I did receive a lot of support from that particular teacher; she would later on become, you know, a very important person in my life, both, you know, throughout my studies and personal life. But the school’s official position at the time was to take no sides because they didn’t want to be involved, you know, they couldn’t afford to be involved in a lawsuit. So, you know, the school’s official position was that they would not be involved. So whatever that teacher or other teachers helped me with was on their own, you know, responsibility.

The above excerpts reveal participants’ contrasting experiences with teachers. While Sandiran’s and Samantha’s experiences were in schools in Canada, Maria’s and Adriana’s experiences were based in Guyana and China, respectively.

Adriana’s narrative reveals the positive contribution a teacher can make in a child’s life. It is noteworthy that even though the school and teachers could not do anything officially, the teacher’s compassion, concern, courage, and empathy played an important role in creating a safe space for Adriana.

Social service organizations and professional supports: Lack of outreach, engagement, and surveillance

It is not that participants didn’t want to access support, but that the supports available failed them. Sandiran painted a picture of the challenges of seeking support:

Like in my neighbourhood[a city in Quebec], it was, it’s a neighbourhood where there’s a lot of community organizations, a lot of mobilization, a lot of mutual aid taking place. Because of our background as South Asians, we didn’t really receive any support from these organizations. We were always othered in the neighbourhood. It was primarily Anglophone and Francophone way, and the Caribbean or people of African descent neighbourhood. And so, that’s whom the community organizations cater to as well . . . and then in CEGEP [college]after I think I had spoken to a physician at the adolescent health clinic who for the first time confided in . . . she really encouraged me to start talking to a counsellor . . . and then that’s when I started talking to a counsellor. . . .This counsellor was a white middle-class, great lady but didn’t understand the realities. And so I spoke to her here and there. And I think the very first thing I told her when I went in was that my father has paranoid schizophrenia, and I saw him beat the crap out of my mother throughout my life. So, it just came pouring out . . . but everyone at [the University] was very trauma uninformed . . . catered to the typical, the default student, someone who has privilege, was upper-middle class, didn’t come from a migrant community. I also had quite a few bad experiences with them.

Sandiran’s negative experiences with community-based organizations speak to the preference and limited scope of specific ethnic neighbourhood organizations, excluding other ethnic communities.

Samantha shared her experiences with a major mental health organization in Ontario and other organizations:

Well, I think that the [a major mental health organization in Ontario] . . . they had her [Samantha’s mother] in this new treatment program, so then they would come and verify with me and talk to me, and that provided a lot of stability because I found it easier to connect with them because their approach was like concrete, and to help me. So I had a lot of support from them. Initially, it was Ontario Works for my mother, and then after her diagnosis with schizophrenia and liver failure, it was to ODSP (Ontario Disability Support Program). So, and you know, the region that we live in is not very ethnically diverse. . . . And I think there was some tension between the social workers . . . and my mother would always be fearful . . . a negative relationship between them. I couldn’t figure out what it was . . . that was a very, very challenging, turbulent experience, and I know they also came and visited her quite often in person and things like that.

Government departments: Mismatch of service delivery models

Sonia and Jay shared their experiences with government departments, such as law enforcement services.

Being an immigrant to Canada, Sonia’s mother lacked the traditional support of the elders she would have had in her home country to intervene when her husband got violent. Sonia shared an experience when her mother called 911 for support, which resulted in her father’s arrest. According to Sonia, there is a need for law enforcement to understand the reason for the call rather than administer a uniform protocol.

This is probably the first time in like a year that he [father] ever did anything, but he like pushed my mom forcefully and then slapped her across the face and like started becoming more physical with her. So she got quite afraid because he’s never acted like, to that extent before. So the first thing she did was call 911. And that was the very first time the justice system has ever been involved in anything relating to our troubles. . . . I get home, and you see police cars, and you’re like I can’t describe that feeling . . . it’s just horrible, and anyways, so my dad was handcuffed and taken away because he was still quite angry he wasn’t coming down. So the police said, “Well, you’re obviously showing signs of aggression; we’re going to take you away.” . . . He can’t just go because she didn’t understand this when she called 911. . . . And if they hadn’t, if they just brought the police to the house and de-escalated him, I think we would have been like, wow, she called cops like I need to get my shit together, so this doesn’t happen again. And he wouldn’t have done that again; I know my dad . . . and everything would have been resolved without this legal piece, which has really messed with all of us.

Jay called 911 when his father hit his mother, and she was injured in the head. However, Jay appreciated the intervention by the law enforcement officers and EMS. In Jay’s opinion, his action has changed the dynamics between his parents:

They came, they checked . . . to see if the person is responding . . . they just checked, my mom’s good okay, they left it, and since that day I always ask my dad, I’m like, “So how was your experience?” So after that, my dad is kind of very like, I would say not controlled, but the way how he would articulate certain conversations with my mom and myself, like despite the age difference, right, is very like respectful, even thought process, right, not only like physical behaviour, just like thought process.

The participants’ reflections on institutional supports reveal that, in most cases, the supports fell short at the most critical time for them. Instead of supporting the participants, the services of institutions such as CPS were negatively perceived and not accessed. Other societal institutions such as schools, counsellors, and law enforcement failed to adopt a trauma-informed, needs-based, culturally informed approach. There is also a critical need for increased awareness of FV as a social issue that moves away from pathologizing families and cultures.

Since the participants rarely accessed social services, we asked what informal supports these families and children accessed to address FV. The following section highlights the informal support received by participants and their families.

Accessing informal supports during family violence

While some participants only accessed support later in life, others sought support from extended family members.

Chiairo, Jay, Maya, Sonia, Samantha, and Viktor received support from their mother’s side of the family. Chiario’s maternal grandparents played a significant role in raising her and her sister and provided stability and security. Maya’s grandmother, mother’s sister [aunt] and brother [uncle] played a vital role by paying their bills, sheltering Maya, and guiding her in her career. Similarly, Sonia also found unconditional support from a maternal uncle and his daughters, with whom she got along very well. Sandiran and Abi, too, spoke of support from their mother’s family. Samantha’s maternal uncle helped; he stayed with Samantha when her mother was hospitalized. Like Sonia, Jay and Anita had a solid support system in their cousins with whom they shared about their family situation.

However, a few participants sought support from friends at varying stages of their life and for various reasons. As a child, Sonia did not seek support from friends, but now that she is older, she feels comfortable talking about her family. Adriana did not confide with most of her school friends, as they were from culturally diverse backgrounds and hence would not understand her situation. She only confided with one friend, who, after learning about her situation, stood by her through all her struggles. Jasmine, who had an intense fear of her father, sought help from her friend to forge a report card to help avert her father’s anger:

Like my friend was actually the one who helped me forge the report card, she’s [South East Asian], and she also has had that experience of having strict parents, so she was like, I’ll help you with this, you know, I’ll help you. And she helped me because I was like, I have no idea how to forge a report card. I have no idea; help me. And she’s like, don’t worry, “I’m gonna Photoshop, I’ll help you,” and she actually helped me make it look pretty legitimate. I was like, wow, you should make a career out of this.

Except for Abi, none of the participants received any support from their father’s side of the family. While Abi stayed at her cousin’s (paternal uncle’s daughter) when she and her mother had a misunderstanding, her sibling Sandiran felt the uncle’s family did not support their family despite being very well off.

Impacts of Experiencing Family Violence

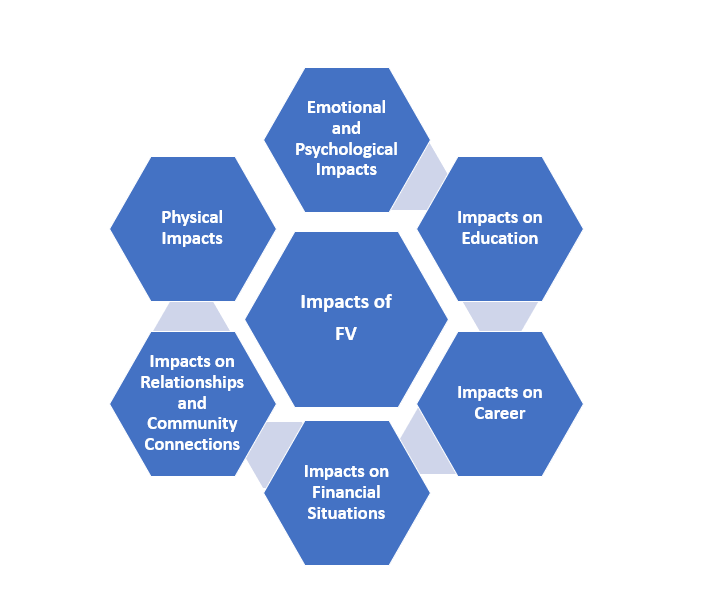

In keeping with the phenomenological approach to inquiry, we focused on gathering information from participants about the impact of FV on their lives. The findings revealed that for each participant, the impact of FV extended to their physical, emotional/psychological, financial, and social dimensions. It impacted their educational prospects, careers, social relationships, and relationships with siblings, parents, and communities. Most participants demonstrated great agency in overcoming the consequences of FV, and a few are still dealing with the fallout. For clarity, we analyze each dimension of the impact separately; however, it is essential to remember that participants were impacted in several ways simultaneously.

Figure 1: Impacts of Experiencing Family Violence

Physical impact

Anita talked about noticing stress lines on her forehead due to the stressful environment in which she was living. She felt that the constant stress, pressure, and anxiety caused premature wrinkling and aging:

Yes, so I feel like I am getting lines on my forehead, and because I’m only 21, I feel like that’s not normal, especially because I’m seeing within my friend circle, my older sister, no one has that except for me, so I felt like I took in a lot of stress, especially because I lived at home. . . . I have more responsibility.

Anita’s statement highlights how siblings experience the home environment differently and are thus impacted differently. Though the middle child, Anita bore the brunt of the situation by taking on more responsibilities, pressure, and stress than her elder and younger sisters. When we think of the impact of FV on a person, we think of mental health, relationships, careers, and the like. While these are real, we often overlook the bodily changes associated with living with constant stress. When one constantly compares oneself to others, the lower confidence and negative self-image that comes with it further impact mental health. Anita’s narrative emphasizes the reality of FV and how this can impact every aspect of one’s mind, body, and spirit.

Jasmine talked about the physical impact of living in perpetual stress due to family violence, compounded by the stress of attending university.

I’ve had stomach problems pretty much since I started university. I would say maybe a year or two into university [it] got worse. I was in and out of hospitals a lot, emergency clinics. .. They could not figure out for the life of them what was going on. I did an endoscopy, and they didn’t find anything physically wrong at the time, and the doctor attributed it to stress. Which I definitely would agree with because I had a lot of pressure with the school. Especially after the first year doing so badly, I wasn’t able to stay in that co-op program, which was the main reason that I wanted to go there in the first place, and that definitely took a toll on my physical and mental health. . . . And I feel like physically. It made me feel more tired, not wanting to do things. . . . And even now, I still have the same issues with my stomach. I did an endoscopy last year, and they found my stomach was inflamed. I have a hernia on my esophagus. So physical issues, I’ve had for years and a lot of it. I would definitely attribute my stress and just my inability to like. I don’t know. I think it’s just me wanting to delay things a lot. Like even seeing a doctor, I delay it because I’m scared to go see the doctor; I don’t want to hear what they have to say to me.

In Jasmine’s case, we can see how discouraging it was for her always to feel physically unwell and her lack of motivation to visit a doctor because of the fear of more bad news. Jasmine struggles with her physical ailment, emphasizing the long-lasting impact of being in a stressful setting.

Emotional and psychological impact

This section presents the multiple emotional and psychological impacts participants experienced consistently and concurrently. Rather than organizing the impacts thematically, we have presented below the actual impacts for each participant to provide an insight into their compounded effect on these individuals.

Self-harm

Witnessing FV impacted Maria’s mental health as a teenager. She described episodes of physical self-harm:

I used to cut myself. My outburst in high school used to be me cutting myself . . . and no one understood it, I didn’t even understand why, but when I was angry, I couldn’t feel anything. And I used to literally just take the razor blade and cut. . . . I never used to feel that much pain when doing it, or maybe it’s just a mind thing. But I used to only cut this hand [left hand], and I tried cutting my foot once because I didn’t want people to see it . . . and then after doing it, I would just feel a sense of relaxation, but it never used to pain me that much like I don’t know why.

Maria was also rebellious in her teenage years:

I think it was me being on the phone, me being rude. I used to have outbursts. I would cry. Like, if they [parents] don’t agree with anything . . . say if I wanted to do something, and they don’t agree, and I don’t get my way, I used to just cry, and rebel like in a rude way. But I think that was me just rebelling in general, yeah.

As an adult, Maria has stopped harming herself but continues to experience anger, disappointment, dejection, and helplessness when she regards her parents’ situation:

I get angry when my mom and dad cannot see eye to eye because I look at other people. I’m like, their family can see eye to eye. Their kid is not involved. They do it just for the kid. And, you know, it’s okay, like . . . before the day before I left Guyana to come here to study, it was the last day I saw my father. He came, and he said he wants to drop me into the airport, but my mom, she’s like no. . . . And then, they had their outbursts. . . . We have a house. He’s outside of the house sleeping in the vehicle. I’m inside the house with mommy sleeping. . . . Now, I’m in a position where I have to choose. And I chose Mom because she’s the reason like she financially did everything for me, and if it wasn’t for her, I wouldn’t even be here studying, and at the same time, I feel sorry for my father. And it was the worst situation . . . that was hard.

Maria vividly described the mixed emotions she has experienced throughout her life for her parents. She struggles with balancing her love for her mother and father, resulting in an emotional challenge.

Stress and anxiety

Chiairo has always experienced stress and anxiety, and these continue even after she has left home for the university:

I was under a lot of stress most of the time because of the way he [stepfather] behaved and also worried about my mother, worried about her wellbeing, her life. . . . I lived in a lot of anxiety because of the situation for a very long time, that persisted even when I left home for school. I think sometimes it even was worse afterwards because I wasn’t close and didn’t always know what was going on. So I think psychologically, there was a lot of stress, I think, physically I reacted to that stress. . . . I think that I don’t totally understand the way that particular experience impacted my mental health because things are always complexly intertwined, but I have struggled with mental health for quite a while.

Chiairo’s excerpt highlights the interrelatedness of physical and emotional/mental health. Hence, the excerpt highlights the need for a holistic approach that responds to all areas for total recovery for individuals affected by FV.

Schizophrenia and low self-esteem

Abi, who experienced severe emotional and physical abuse as a child, has struggled with acute anxiety, schizophrenia, and low self-esteem. Abi felt that her mental illness affected her academic success and employment prospects:

I don’t know if it’s because of what happened in the past. But I’m more than the average person. I’m anxious. . . . And I also have a diagnosis of a mental illness as well. I also have schizophrenia. . . . And if I compare myself to somebody my age, I’m not as functional as somebody else my age would be, and I’m a lot more stressed. I have more barriers. And so, like life is a lot harder to live. . . . I have very low self-esteem. . . . I know that I have insecurities about being a racialized individual and, you know, as a woman as well . . . like, it has impacted my self-esteem to the point where I’m not . . . able to ask for my needs as, as clearly as I would like to. For example, accessing healthcare services . . . I don’t put my foot forward . . . I’m more of a passive person. . . . It all has contributed to the person that I’ve become . . . I do feel inferior, and I do feel like I’m, I’m viewed a certain way. . . . With my education, with my anxiety, like, it’s so much harder. . . . I started university ten years ago, and I’m still doing my undergrad.

Abi revealed how mental illness has impacted her life and made her dependent on her already overstretched mother and brother. The excerpt also reveals Abi’s awareness of racism in healthcare and other services discriminating against racialized individuals.

Depression, fear, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

At a young age, Samantha had to take on the multiple responsibilities of caring for her mother, who is living with schizophrenia and liver failure. She has dealt with CPS, OW, a major mental health organization in Ontario, and immigration lawyers, besides financially supporting household expenses in Toronto and sending a monthly allowance to her siblings in Pakistan. Until her immigration status was stabilized, she experienced intense fear of being sent back to her father or foster care. The impact of this stress, navigating various institutions, and caregiving has impacted Samantha, who has recently been diagnosed with depression, fear, and PTSD.

Lack of trust, social isolation, depression, and mental health diagnosis

Childhood experiences of abuse caused Sandiran to become distrustful of people. They experienced severe mental distress in their childhood and have experienced suicidal thoughts since childhood.

Constant, constant isolation. And, you know, I don’t remember telling myself anything in particular, apart from don’t trust these people, as in, don’t trust everyone who essentially fails you. . . . It was more so how I constructed the world around me and how I understood it. I understood it as a place where people didn’t give a shit. I understood it as a place where . . . no one was there to help; no one was there to support. . . . I understood it as a cold place . . . over the course of my life, over the first 17 years of my life . . . I experienced severe forms of mental distress. I was heavily, heavily, heavily depressed, suicidal as well. There essentially was no day over my 17 years, honestly like it’s not even to over exaggerate, but never a day when I wouldn’t think about jumping off the balcony, throwing myself in front of like a car or bus or the metro. And I also tried to take my own life a couple of times as well. And this was . . . as young, as eight, nine. . . . I responded in sort of internalizing a lot of that and wanting to self-destruct in many ways.

Sandiran continued:

And then, I think, just over the course of my university. . . I was also going through like quite a bit of mental health challenges, internally. Tried to get help in different ways, but it’s, it’s, I think a lot of our mental health structures just don’t understand the interplay of trauma, structural and social factors. . . . I visited [Sri Lanka] because I wanted to essentially go and listen to people’s stories. . . . I wanted to know about my parents prior to them being my parents too. But what ended up happening was that it was a very stressful environment . . . and that really set me off. And I essentially like developed like very harmful thoughts that were pre-sort-of psychosis and like had some forms of delusional thinking as well. And, you know, it’s, and then I reacted in ways where I was very aggressive, not physically, but more emotionally like with my mum. I was very impatient; I was yelling, you know, internalized a lot of the ways. . . . I saw my parents react to their mental health; I repeated that in my own circumstances, and . . . after coming back, I developed some worse situations of psychosis and ended up like almost taking my life as well. . . . As a person, I was disintegrating, and it was like, I could feel the devil within me . . . I could see myself change in the mirror; I could see, like, when I was walking through the world, it was like I had holes in me where things were passing through.

Sandiran’s narrative paints a vivid picture of the impact of experiencing FV and the incremental worsening of the impact over time. Sandiran’s construction of the world and isolation from others indicates the meaning they made from the lack of support their family received from extended family members, the ethnic community and the larger society. The excerpt also shows that their mental health challenges magnified and took a much more severe form without timely support. Sandiran’s reflections on the lack of mental health services that address the impact of war trauma and structural and social barriers are significant if individuals and families like Sandiran’s are to be supported.

Suicide attempts, nightmares, panic attacks, depression, and PTSD

Adriana described repeated suicide attempts and the panic attacks she suffered while living with her abusive father, and her ongoing battle with depression as an outcome of the trauma she experienced:

For me personally, as a result of this, I considered suicide multiple times. I felt like there was no escape, you know, even if at that time when I was 16 years old, it felt like even if I managed to run away from home, where would I go. . . . I had no one to trust, no one who could help me, you know, the law wasn’t going to protect me in that case; they would return me to him [father]. And I felt very hopeless, I felt very helpless, and so I considered suicide. . . . I tried to burn myself on the radiator. I tried to swallow toothpaste to make myself sick to go to the hospital because going to the hospital was like a holiday to me. . . . I would have nightmares. . . . In my nightmares . . . my father would abuse me or my mother, my nights would be very restless, I would not be able to get enough sleep, and then second of all, the sleep quality wasn’t that good either, even if I managed to get some. . . . In my nightmares, I’m always being chased by my family, I’m always being stabbed by my father. There were multiple occasions in my nightmares where my father stabbed all of my friends whom he believed that has helped me, and I saw all of my friends get killed because of me. . . . For a long time after I left and after that incident where they dragged me from this seventh floor to the first floor, every time I opened the door afterwards, I would pause for a second . . . I would take a deep breath. I would stop breathing actually until I open the door and make sure that no one is in there, then I would be able to take a deep breath. . . . Whenever I saw a car in the street that looks like my father’s car I would, you know, stop for a second, you know, and think “Do I need to run, should I run?” . . . So I would say the most severe impact is definitely mentally. Even though I’m physically removed from that situation, however, the psychological damage is very hard to repair, especially when it’s a sensitive person. I still experience nightmares. I do have panic attacks and mental breakdowns sometimes. I am currently waiting to have a psychological evaluation, and I am taking antidepressants, yep.

This excerpt reveals how an individual’s experience and perceptions affect the impact of FV on their physical and emotional/mental health. The excerpt also conveys the significant impact of FV on the participants regardless of when and for how long the FV lasted. Its impact persisted as they grew into adults, and in some cases, this is when the impact became more vigorous because they were more conscious of the reality of events. The findings also demonstrate the urgent need for trauma-informed mental health supports and redressal of structural and social barriers experienced by racialized immigrant families like Sandiran’s.

Supports accessed for emotional and mental health

The interviews revealed that several participants accessed counselling services to address the continuing impact of FV. Chiairo, Sandiran, Abi, Samantha, and Jasmine accessed counselling services at their universities, and Maria and Sonia accessed private counselling services. While in high school, Maria went for counselling, and Sonia went for counselling after her father’s arrest in the recent past. Jasmine was satisfied with the counselling she received. Abi and Chiairo are still going for counselling, and for Abi, counselling has helped re-establish her broken relationship with her mother. Chiairo is accessing various types of psychiatric treatment for her depression.

Despite her diagnosis of depression and PTSD, Samantha has not accessed any support, as she does not feel the need. Maria, Sonia, and Sandiran accessed counselling services but found them unhelpful and discontinued them. For Maria, counselling did not help her with her self-harming behaviour, and for Sonia, it did not offer anything beyond a cathartic release, which she felt she could do on her own. Sandiran found that counselling is designed on the cultural norms of the dominant western society and did not acknowledge war trauma and structural and social barriers experienced by racialized immigrants in Canada.

Impact on education

Several participants spoke about the impact FV had on their education. While some participants struggled to focus on their education, others used school as an escape and a coping mechanism.

A rocky, evolving journey towards success

Jasmine talked about her difficulty focusing on her education. She felt that she did not experience a normal childhood in her home:

When I was in university . . . I chose to distract myself with life, other things, fun things, parties, friends. Things that I probably should have focused on when I was younger. But when I was younger, I didn’t really have a chance to do that, you know. I was sheltered; I wasn’t allowed to go to parties, or sleepovers or hang out with my friends every weekend. I didn’t have those normal childhood experiences. I was home a lot . . . school was the least of my worries. . . . My grades only got better once I left university and started the [attending an assaulted women’s support program]. I had a better handle of myself and my mental health, and my parents were also communicating with me better.

Jasmine’s experiences reflect that of many racialized immigrant communities where parents want their children to focus on education. Sandiran referred to this as “model-minority pressure,” which we discuss below.

In her interview, Chiario stated,

I still worry about her [mother] a lot . . . you know she’s dating again. And I’m, I’m constantly worried . . . it’s gonna happen again, and I think that that is distracting, and that does sometimes make school quite hard.

Samantha’s journey in education evolved over the years. As a student in Canada, she started from a low point but excelled over the years when she realized that her school was the only source of stability and refuge. She narrated her journey thus:

I was a very bad student. You know my report cards, they are like Cs and Bs cuz I was out of school. You know I had very bad English surprisingly . . . I had to repeat kindergarten like one year because . . . they said that she’s just so lagging, mentally, like let’s put her through one more year . . . then I moved back to Canada. I could not directly talk to other people normally, right, because the kids that their worries were like video games, and I was like, you cannot connect with them. So I think academically I was challenged at that point because of the social environment. . . . And then, throughout until grade eight, I started getting really good grades, and in grade eight, I actually ended up being valedictorian, so it was like, the top academics, like everything right and from math and science specifically. And I was surprised. I got this like award for leadership, and like, I got to give a speech and stuff for my class, right? And you have to understand, like that same year, like I had been staying with family friends and trying not to get in foster care and stuff, right? So for me, like, it [school] provided a lot of stability. I liked it, I loved reading and stuff, so I think once that happened, academically, and so I thought I found a lot of refuge in school personally. I continued to do well in high school. I got a full scholarship to [name of the university in Ontario].

Contrary to Samantha’s description of the school as a source of stability and refuge, Maria talked about teachers who judged her and discouraged her from becoming a nurse. This caused her to lose her focus and motivation to study. It was not until Maria switched to psychology and found nonjudgmental professors that she began to excel in school. As she described, studying psychology allowed her to fall in love with herself and understand those around her more.

Unlike Samantha and Maria, Maya’s performance in school was affected by her caregiving responsibilities toward her siblings, which curtailed her opportunities to focus on her studies and take up extracurricular activities. However, Maya realized the negative consequences of not doing well in school. On receiving advice from her grandmother, a nurse herself, to pursue nursing, she found a goal and direction to do well in school. She also found ways to engage in extracurricular activities and transition to becoming an academically strong student.

This theme highlights the factors contributing to participants’ motivation to study and succeed academically. Even though their journey was difficult, they succeeded by using their capacities of critical thinking and reframing, openness and receptivity towards others’ ideas, and creativity in developing conducive conditions for their success.

Goal-directed journey towards success

Sandiran spoke of their focus on academics amidst the challenges posed by FV:

I remember this, like, very clearly, I had a biology test right before the first crisis with my sister, and she had tried to hurt my mom, and I was terrified. I called the cops, you know, gotten her to the emergency. . . . I had spent the night with her at the emergency, and the next day I went in to write my bio test and . . . it was so seamless in a way just because it was such a constant in my life to have to do that, to have to deal with something so chaotic in my home life and then be able to go to school and then, it was all normal, it was okay. It was . . . ridiculous in some ways, but it, I think, it affected my school to a certain degree where I was able to have the language now, like I was able to use these lived experiences to enhance my learning . . . There was just a dissonance between academic life and life in reality.

Sandiran elaborates further on the challenges of studying during the pandemic: