12 OpenTextbooks in Canadian History

John Belshaw

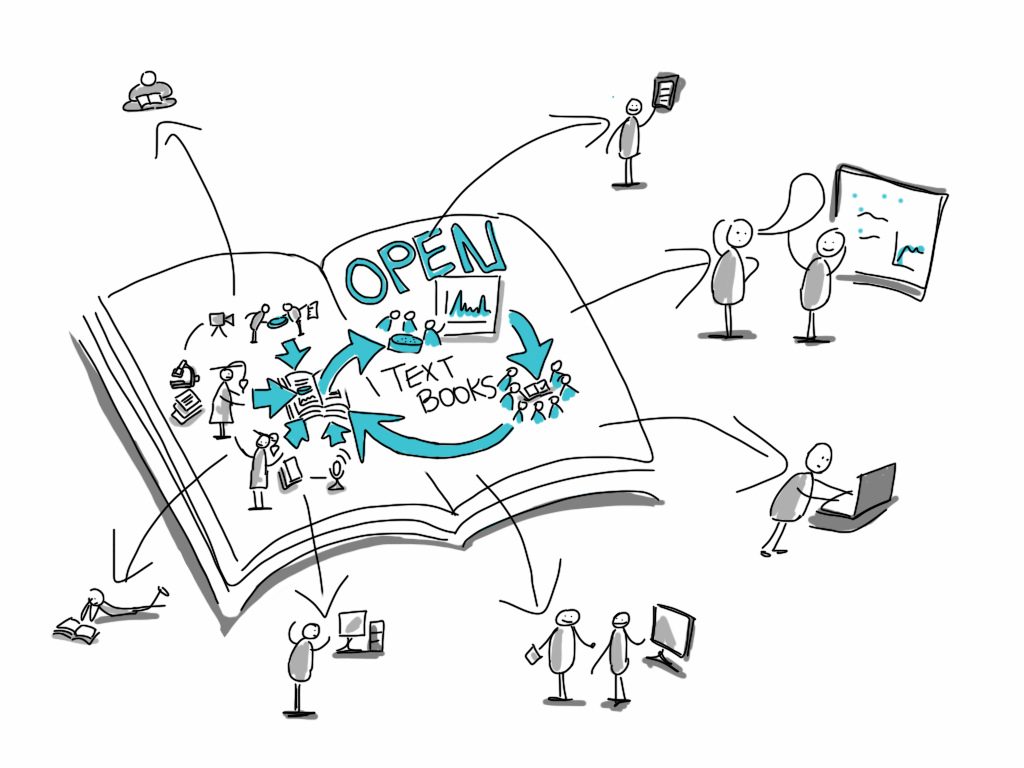

I had this ‘eureka’ moment in the barber’s chair. Well, I thought, if a book is like a railway line, heading in one direction from west to east, then an e-book is more like a mine elevator, heading from the surface into the depths, from top to bottom or, perhaps, from north to south. If that’s the case, then an OpenTextbook is like a hive. It is living, fluid, with junctions that run up, down, outward in several horizons but also in three dimensions. It offers options rather than a singular pathway, complexity rather than guiderails, a little more risk but the possibility of greater rewards.

Moving from metaphor to practicality, the OpenTextbook is just plain different from conventional textbooks. For starters, it’s smart. It can evolve. Instead of waiting for the (inevitable) umpteenth edition, you (the prof) can refine and effectively create the newest edition. What if your textbook could be made to look more like something from Harry Potter, with moving images on the page? What if it could function differently?

What if it was available for free?

A couple of years ago the Province of British Columbia’s Ministry of Advanced Education was asking questions about the costs of post-secondary and the barriers students faced to accessing higher ed. One cost, of course, is textbooks. At that time, for example, the text we were using in our courses at Thompson Rivers University – Open Learning cost $88. Other intro texts in the Social Sciences, English, and the Sciences – the usual suite of courses taken by first and second years – generally sell for much more. It’s quite possible that a first-year student could spend over $1,000 on textbooks.

Or not. And that’s what the research points to. Potential students decide to forego higher ed because they cannot afford it. Or they enroll and balk at paying hundreds of dollars for texts that they can’t resell later on because (you know what’s coming) the next edition has rendered them unusable. The planned obsolescence of the university textbook has thus become a real hindrance to students maximizing their learning potential. Sure, some photocopy like mad (thereby violating all kinds of copyright) and some share, but it would appear that many – reckoned to be between a quarter and a third of a class – simply don’t read the text.

On October 16, 2012 at the annual OpenEd conference in Vancouver the then Minister of Advanced Education, John Yap, announced the BC Open Textbook Project with support provided by BCcampus. The goal was to make higher education more accessible by reducing student cost through the use of openly licensed textbooks. Specifically, BCcampus was asked to create a collection of OpenTextbooks aligned with the 40 highest-enrolled subject areas in the province. And it came to pass that I authored the one on Pre-Confederation Canadian History.

Writing a survey text is a very different proposition from preparing an original monograph. Writing an OpenTextbook is still more different. Both require a careful synthesis of existing research, which is fairly obvious. But when one begins that process it rather quickly becomes clear that the meta-narrative might need a bit of tweaking. It’s no surprise that we get stuck in well-worn channels of thinking and that, despite our best intentions, we find ourselves in Week 13 marching down the “Road to Confederation.” Immersed in as much new literature as one can manage and carefully reading familiar narratives obliges the writer of the synthesized text to ask questions about why we think things happened the way they did and why we apportion importance to one event but not to others. What was the turning point? What was the agenda?

That’s what’s common to both the hardcopy and OpenTextbook project, but what distinguishes them is two things, one obvious and the other less so. Obviously, the OpenTextbook exists in an electronic form principally, although it can be printed out. That creates opportunities for experimentation with and inclusion of different media. You no longer have to worry about printing costs so all kinds of bells and whistles can be packed into sidebars and hyperlinks. It can become a vastly enriched document. The second difference is that the world of OpenTextbooks adheres to different rules. When you first encounter a herd of OpenTexts they will be running free across the Creative Commons. They dwell outside the boundaries of conventional copyright.

There are three reasons why anyone teaching or studying introductory history ought to be excited – or at least curious – about OpenTextbooks. First and foremost – and most likely to appeal to us cheapskate Canucks – is that they are free to use, order, assign, etc.

By “free,” I mean, um, free. There is no charge to use them. They don’t come cheaper in a bundle , there’s no special password that you’ll have to buy, no account info you have to submit, there’s no clock ticking in the background and there’s no best-before date. They’re free. Free of charge. Anytime, anywhere. I just looked at one on my smartphone. I paid for the electricity, yes, okay, that’s true. You got me there.

It’s the two extraordinary things one can do with OpenTextbooks, however, that make them most appealing. First off, any instructor can edit the textbook. It might be something simple, like changing up the Suggested Readings. Or perhaps the little learning tasks currently in the OpenText don’t work in your course or in your jurisdiction. It’s a work of synthesis so it is completely possible that some of the information is even now out of date. Or wrongly synthesized. Perhaps you know something about a particular issue, something that no one else is likely to know. Or you find an error (that happens, sure, mea culpa). So change the textbook. Fix the mistakes, add details, write a whole new chapter, or excise one that you don’t like.

In short, instructors using the OpenTextbooks are, for once, not excluded from the process of creating the teaching instrument. You can do as little or as much as you like.

Better still, consider having your students do so. This option allows you to move beyond the “disposable assignment” and create something of lasting value. In all likelihood there are some chestnut assignments that show up in your course. Perhaps it is that perennial essay on the causes of the Rebellions of 1837 or the good ol’ Origins of Confederation. Consider asking a group of students to look at several different interpretations of such topics. They can highlight the differences between historians’ positions, the kind and use of evidence, the ways in which successive takes on the event(s) have been shaped by the historiography. They could write that up and, if it passes muster, you can add it to the OpenTextbook.

Or take a bigger risk: have them create a visual debate. One of the best I’ve seen thus far in this kind of environment involved stripping the sound from a video of the Nixon-Kennedy debate of 1960 and providing voice-overs for the two grainy figures as they discuss some aspect of the course material. (I’m part of a team that is interviewing historians on their areas of expertise for a set of HD videos: we’re going to drop them directly into the text. Your students could do something similar.)

The point is, the textbook is no longer sealed in shrink-wrap. It’s yours to play with. Reuse, remix, revise, retain, redistribute – the five Rs of open education resources. This is possible because OpenTextbooks are leased using a Creative Commons license. As most readers of ActiveHistory will know, the Creative Commons is the organization that develops, supports, and stewards the sharing of materials through their free legal tools, like the CC license. a place in which writing and visual records (and other artifacts) are shared. Depending on the kind of license in place, the document may be copied, modified, and repurposed with attribution but without written permission of the copyright holder. OpenTextbooks are part of that tradition and set of practices.

I look forward to discussion about how this might unfold. There have been many survey textbooks before, competing in the marketplace of academia for adoptions. There was a wonderful CD-Rom on Post-Confederation that came out about a dozen years back. At the end of the day, however, the question was essentially, “which of these do you want your students to buy?” Now, the question is “why would you ask your students to pay for something static when there is something dynamic and freely available, something that you can yourself tailor to meet your needs?”