11 Planning Your Open Textbook

When writing a textbook, keep “some possible pedagogical use cases in mind.” As the author, you may have an idea of how you would want the textbook to be used, but other instructors will “define reading assignments (textbooks as a whole or portions of it) in function of their pedagogical objectives. These may not be compatible with your original intent as the author.”[1]

How can you ensure that your textbook is of the greatest utility to other instructors? The way that you select and organize your content will determine how useful the book will be as an instructional tool.

Setting Learning Objectives

Before beginning to write, think about planning your book chapters in terms of desired learning objectives. By the end of the chapter, what should students be able to do? Setting learning objectives will help you determine the level of the material, the content you include, and help design any assessments that might be included at the end of each chapter or section. “Usually in textbooks, objectives are not just used to plan the text, but they are made explicit [to readers]. Objectives can be written out at the start of chapters and/or sections or inserted where appropriate.”[2]

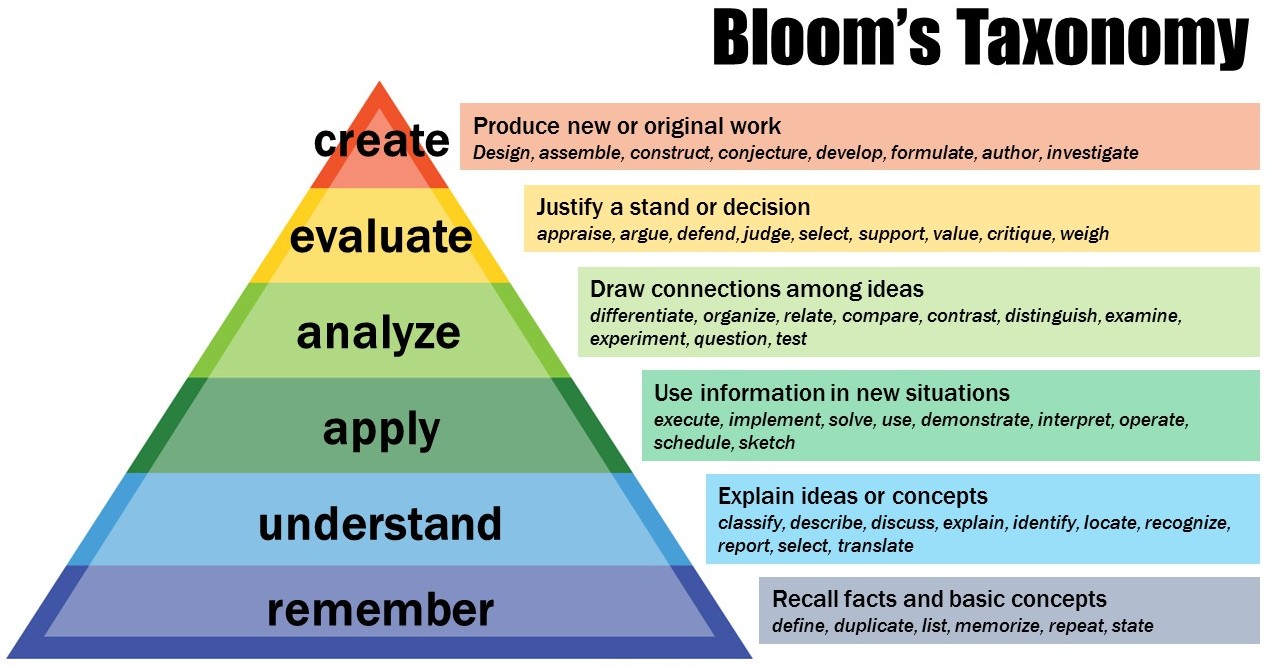

Learning objectives for your textbook can be written using Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The taxonomy has six levels, moving from the least complex type of learning, “Remember,” to the most complex, “Create.” An effective learning objective will use an appropriate action verb to define the level of learning. For example, “By the end of this section, learners will be able to organize their textbook content according to Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives.” By using the verb “organize,” the level of learning is set at the “Analyze” level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to write learning objectives for each chapter can help you keep the level of your textbook consistent (for instance, an introductory textbook aimed at first or second year students may never move past the “apply” level) or to help you structure your chapters so that they build on each other, moving from a low level to a high level of learning.

Selecting and Organizing Your Content

Most textbooks follow a specific framework. For example, chapters typically correspond to major topics, and sections within each chapter correspond to “major subtopics, i.e. a independent unit of instruction. Sub-sections usually cover a concept or procedure to be learned.”[3] The size of your textbook, the number of topics, and the way those topics are divided are determined by how you intend the book to be used. So for example, you could think of a textbook chapter as corresponding “to a week’s work, e.g. two classes and a homework assignment.”[4]

Each chapter and section should follow a consistent pattern. One way to think about designing each chapter is with Robert Gagné’s “Nine Events of Instruction,” as described in Gagné and Briggs’ book, Principles of Instructional Design (1988). The “Nine Events of Instruction” are as follows:

- Gain attention

- Inform the learner of the objectives

- Stimulate the recall of prior learning

- Present the content

- Provide guidance

- Elicit performance (practice)

- Provide feedback

- Assess performance

- Enhance retention and transfer of learning [5]

In his Textbook Writing Tutorial, Daniel Schneider breaks typical textbook chapter elements into four categories – openers, integrated pedagogical devices, interior features, and closers.[6] Each of these categories can be mapped to Gagné’s “Nine Events of Instruction.” Opening elements gain the learner’s attention, inform the learner of the objectives, and stimulate the recall of prior learning. Integrated pedagogical devices and interior features help present the content and provide guidance. Closers elicit performance, provide feedback, allow for self-assessment, and enhance retention and transfer of learning.

According to Schneider, typical elements for each of these categories are as follows:

Opener Elements

- Overviews (or Previews)

- Introductions

- Outlines (can be in text form, bullets or graphics)

- Focus questions (knowledge and comprehension questions)

- Learning goals / objectives / outcomes / competences / skills

- A case problem or relevant real-world example

- In addition one may use “special features” inside chapters, e.g. vignettes, photos, quotations, …

Integrated Pedagogical Devices

- Emphasis (bold face) of words

- Marginalia that summarize paragraphs

- Lists that highlight main points

- Summary tables and graphics

- Cross-references that link backwards (or sometimes forwards) to important concepts

- Markers to identify embedded subjects (e.g. an “external” term used and that needs explanation)

- Study and review questions

- Pedagogical illustrations (concepts rendered graphically)

- Tips (to insure that the learner doesn’t get caught in misconceptions or procedural errors)

- Reminders (ensuring that something that was previously introduced is remembered)

Interior Features

- Case studies

- Profiles

- Problem descriptions

- Debates and reflections

- Primary sources and data

- Models

Closers

- Conclusions and summaries (may include diagrams)

- List of definitions

- Reference boxes

- Review questions

- Self-assessment (usually simple quizzes)

- Small exercises

- Substantial exercises and problem cases

- Fill-in tables (e.g. for “learning-in-action” books) to prepare for a real world task

- Ideas for projects (academic or real world)

- Bibliographies or annotated links

Pressbooks provides a set of pre-made box features that you can use to structure your chapters:

- Learning Objectives

- Key Takeaways (can be relabelled as Key Terms)

- Exercises (or related items such as Answers, Questions)

Learn how to use these features in the Layout section of the Style Guide chapter.

Using Chapter Prototypes

Traditional textbooks publishers often plan out how a textbook will work by developing a chapter prototype. Chapter prototypes can help you plan and embed instructional and assessment strategies, determine an ideal typical chapter length, and work out other design features. You will have the opportunity to think through, for instance, how you will set apart case studies, or if you want assessment questions at the end of each chapter.

By creating a full fledged sample chapter you can work out a road map for how you complete the rest of the book, which can be very useful if you have multiple authors working on the project. It also gives you something to show others to promote your project, even when the rest of the textbook is still in progress. Getting graphic design help to plan the layout of your textbook can also be helpful at this stage, as that can give you a guide for a consistent look of the book as well.

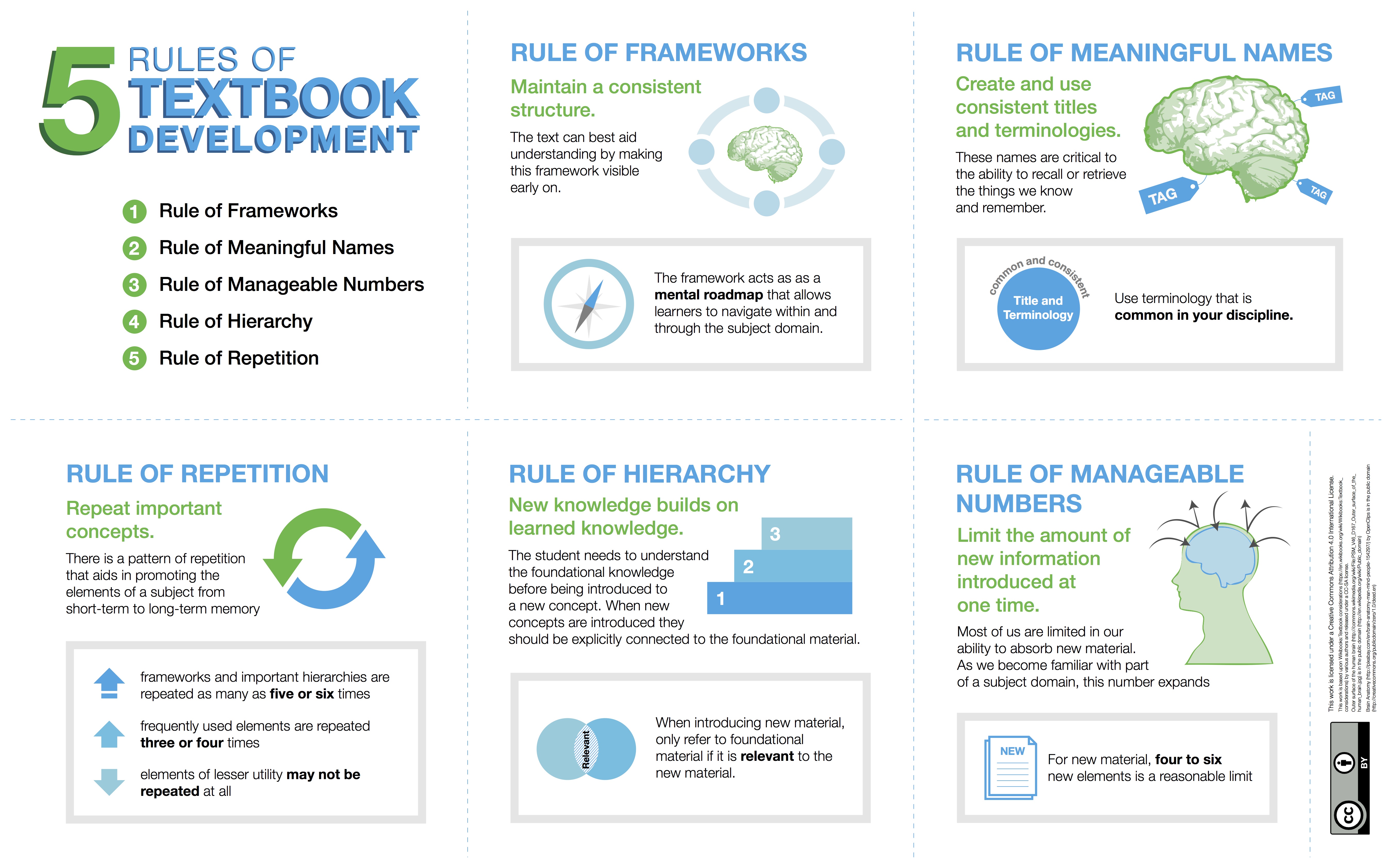

The following image, “5 rules of Textbook Development,” provides a simple set of rules that can help you review your chapter prototype:

- Schneider, D.K. (2008). "Textbook Writing Tutorial." Edutech Wiki. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Gagné, R.M., Briggs, L.J. (1988). Principles of instructional design. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ↵

- Schneider, D.K. (2008). "Textbook Writing Tutorial." Edutech Wiki. ↵