Introduction – Scramble for Africa

Though it was Africa where Europe first honed its colonial practices during the fifteenth century, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that Europeans began to make forays beyond Africa’s coastlines. What changed by the mid-1850s was the use of quinine, a medicine produced from the bark of the cinchona tree. Quinine was an effective treatment for malaria and by 1850 had been developed enough to allow for its large-scale use, making it easier for Europeans to live in the tropics without risking lethal illness. As a product found only in the Andes mountains in Peru, and brought to Europe by the Jesuits during the seventeenth century, the medicine usefully reveals the self-fueling cycle of European imperialism whereby a commodity from Spanish America served to underpin Europe’s expansion into Africa.

Access to the interior of Africa held out much promise for Europe and its business elite, whose wealth had grown over the centuries through the militarized exploitation of commodity frontiers and enslaved labour. Furthermore, the raw materials available in Africa- such as palm oil, rubber, cacao beans, and ivory – promised to propel the continent’s further industrialization.

There were two main fronts of European invasion into Africa. Under French direction, the Egyptian government built the Suez Canal during the 1860s, connecting the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. Managed through a private company, by the 1880s, the British had gained control of the canal and most of Egypt and the Sudan. On the other side of the continent, along the banks of the Congo River, France, Portugal, and Belgium all sought inroads and control.

A prominent player in this expansion was American Henry Morton Stanley, who worked on behalf of Belgium’s Leopold II, making treaties that would enable to king to harvest ivory and rubber and claim these territories as his personal possession. By the time Belgium annexed Leopold’s Congo “Free” State, millions of people had died and millions more had been mutilated as a result of quota rules that required victims’ hands as evidence.

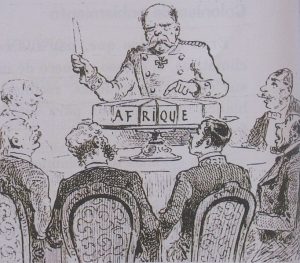

Although European behaviour in Africa was incredibly violent, in order to prevent violence between European powers, in 1884 German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck called together diplomats from most of the European powers (and the United States). The aim of the meetings was to clearly delineate between each nation’s interests in Africa and to set about the terms under which European powers would interact with each other when it came to the continent. No Africans were invited to attend. Before the conference most of Africa remained beyond Europe’s direct influence. By the end of the century, about 90% of the continent was claimed by a European power.

As you read through the agreement struck between the Europeans, consider the following questions:

- What impact would each of the Act’s chapters have on Africans?

- What perspectives did the diplomats take to trade?

- In what ways was the diplomacy in Berlin similar or different from other European practices examined in this book?

This module was last modified in December 2021.