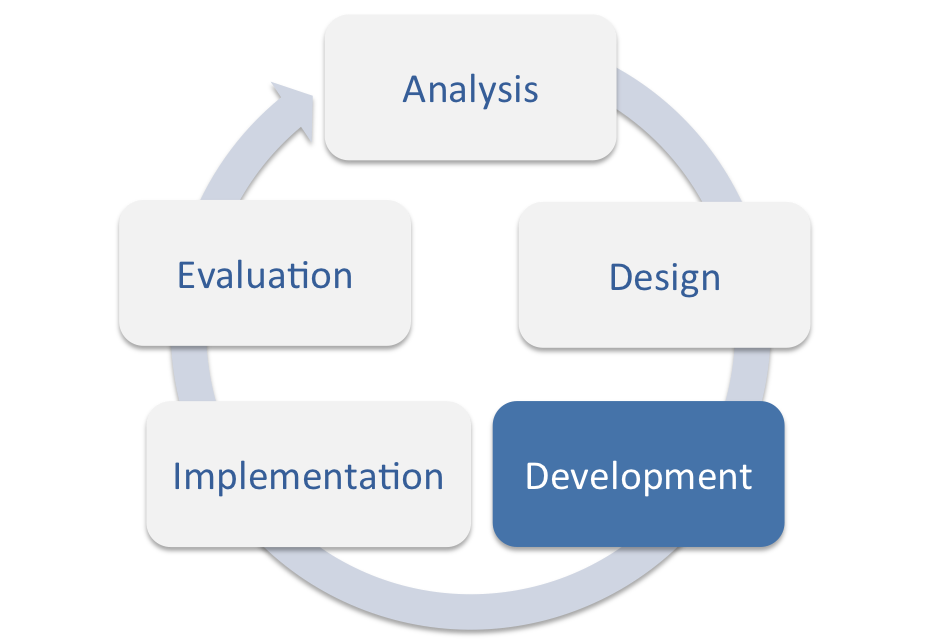

Development

The development phase of the ADDIE process comprises the work of planning and documenting learning activities, assessments and approaches to instruction. Assessment design and lesson planning can be more complicated activities in experiential education courses than they typically might be in more traditional forms of courses simply because the instructor does not have the customary benefits of having as much direct, regular contact with students as other forms of courses allow. When students are on placement, working in the field with employers or community partners, the time that they spend together with their instructor in a synchronous physical or virtual learning space is likely to be different than in other courses. Adjustments in lesson planning, the assignment of student learning activities, and assessments need to be made to ensure that students remain focused on the educational purpose and intended learning outcomes of their experience, that they are prompted to reflect on their progress and connect their experiences to their program of study, and that the chances that they will become overwhelmed or feel adrift or at risk in their learning are lessened.

Try to be both anticipatory and empathetic while developing experiential learning course activities and assessments. As best you can, imagine how you might be able to predict reliably what interventions students will need and when they will need them to advance their learning. Place yourself in the position of your students and endeavour to imagine what learning materials and supports they will need to draw upon at various times during the hands-on experiences that they are engaged in – consider when they will need scaffolding and what that scaffolding might look like for them, when they would benefit most from greater independence and free exploration, and when it might be most conducive to their learning to prompt them to pause and reflect and aggregate their learning. Think about how much time they will really be able to devote to the activity or assessment you assign given the demands of the experience itself and ask yourself when and how you would be most likely to capture and focus their attention best or fairly assess their progress based on their best effort to respond to your assessment activity. Consider as well when your students might learn best from a timely formal lesson, or brief email reminder, or guiding discussion board post, or from the benefit of your presence in physical or virtual office hours or during an organized site visit at the location of their experiential education placement. Develop lesson plans and assessments accordingly.

Also remember that the college or university instructor is not alone in guiding the student along during experiential education. The employer or industry or community service partners are also in contact with the students routinely and involved in coaching them through their experiences on a regular basis. To avoid working at cross purposes with external partners, as an instructor, it is useful to be deliberate in planning the nature of the relationship with the external partner in advance when developing learning activities and assessments and clearly defining roles and responsibilities toward student learning so that the partnership is formed on the basis of trust and understanding. Ensuring that partners understand the intended purpose of the experience in the broader development of student learning in the program of study will lessen the chances that students veer off course, are stretched too far or challenged too little in their experience. Industry or community partners who are alert to the instructor’s teaching and learning plans and assessment priorities, and know how they can contribute to or support those plans specifically, can assist in ensuring that the students have a smooth and coherent learning experience. It is also important for the educational institution (including the instructor) and students to understand and appreciate that the industry or community partner in experiential education may have other priorities than contributing the education of the students, or additional goals for partnering in experiential education. External partners may be more motivated by the opportunity to influence and preview future prospects for employees or benefit from economic, social and political incentives to participate in experiential education. While external partners can provide current and authentic insights into the specific knowledge, skills and values required of their employees, where experiential education leads to credit for learning, colleges and universities have a vital role to play in assisting external partners to understand the ways in which postsecondary institutions endeavour to prepare students for entry into the workforce, as well as cultivate their broad-based skills and love of learning.

Working in advance with the partner(s) to negotiate the substance, pace and organization of the student learning experiences can also help to align experiences with the needs and interests of the external partner(s), the college or university and the students. Linking experiences to the program learning outcomes, and knitting together what the student is doing in their experience with complementary teaching and learning activities and assessments of learning, will help to ensure that the experiential education opportunity does not hang off the side of a program of study. External partners can play a pivotal role in reinforcing and deepening student learning. Negotiations of roles, expertise, and commitments are critically important to the success of the experience for all parties involved. Pause for a moment to consider how instructors and external partners can collaborate effectively on the identification and negotiation of roles, capabilities, goals and priorities with reference to the development of teaching approaches, learning activities, and assessment planning?

In this course, you will need to think carefully about how you will create a complementary plan instruction that will work well for the goals of the academic program, you, your external partner(s), and most importantly, for your diverse students who are busy learning on co-op, practicum, internship, service-learning, or conducting field work or engaging in an applied research project. As you begin to develop your teaching plans and assessment, choose your one week or module carefully, ensuring that it is well suited and well-timed for a formal lesson plan and assessment.

Reflection is a critically important component of experiential education and can be incorporated effectively into both formative and summative assessments. As Mezirow reminds us, “much of what we learn involves making new interpretations that enable us to elaborate, further differentiate, and reinforce our long-established frames of reference or to create new meaning schemes. Perhaps even more central to adult learning than elaborating established meaning schemes is the process of reflecting back on prior learning to determine whether what we have learned is justified under present circumstances.” (Mezirow, J. (1990). How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood, 1, 20.). When we critically reflect upon our learning experiences, we can better determine what knowledge, skills and values we have cultivated and which we need to develop further. We can also consider the range of circumstances, and the extent to which, we might be able to transfer and apply new learning. Consider adopting the three step DEAL (description of experience, examination of experience and assessment of learning) model to guide your efforts to design an effective reflective assessment tool for the students enrolled in your course. You can read more about the DEAL model in Ash and Clayton (see: Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 137-154; and Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning) as well as Stirling et. al. (see: Stirling, A., Kerr, G., Banwell, J., MacPherson, E., & Heron, A. (2016). A Practical Guide to Work-Integrated Learning. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from http://www.heqco.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/HEQCO_WIL_Guide_ENG_ACC.pdf).

.