Design

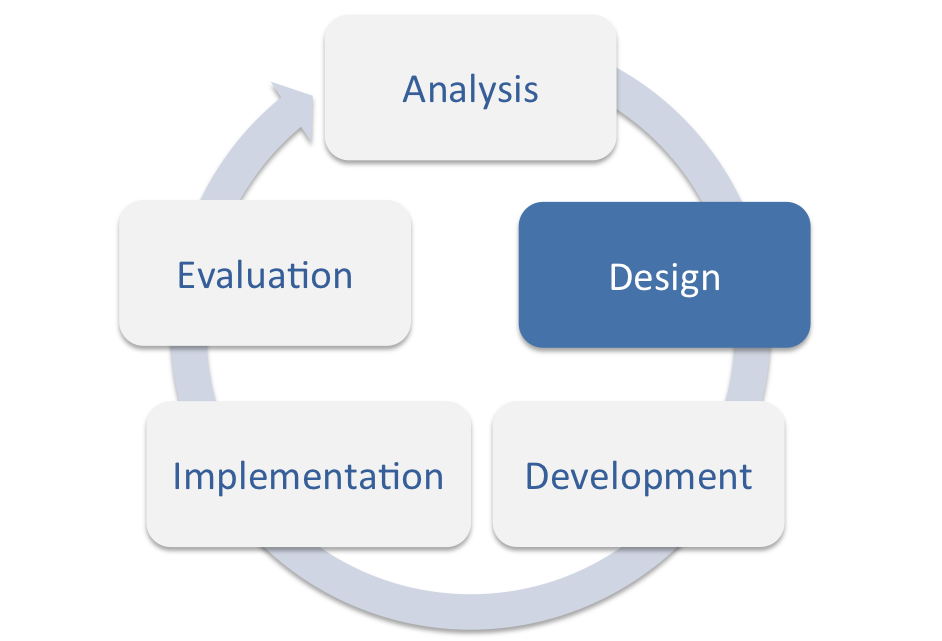

Although experiential learning comes with unique considerations for instruction, the various forms of experiential education fundamentally remain structured and planned educational opportunities, so there is still benefit to applying three effective and connected approaches to course design: Understanding by Design, Backward Design (with a focus on constructive alignment), and Universal Design for Learning. As we consider these three approaches to course design, it is useful, however, to interpret the lessons of these approaches through the filtered lens of the application to specific types of experiential education.

Understanding by Design (for greater detail, see: Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Ascd.) is a planning framework for course design that aims to ensure that students really possess their own learning rather than merely encounter knowledge, which means that what the students do with the core content, essential skills and habits of mind bound up an a course takes priority over what the instructor does with the core content, essential skills and habits of mind during the course design and delivery processes.

As a model, Understanding by Design relies upon a backward design processes. Backward design is an approach to creating curriculum that places intended student learning outcomes are at the heart of lesson planning and that teaching methods and assessments are geared to deepening student learning and helping them to transfer and apply their learning effectively across situations. The simplest way to explain this approach to curriculum design is to say that it begins with the complete set of final, intended learning outcomes in mind and works backwards to consider the ways in which students should be able to demonstrate their knowledge and the most productive teaching methods to help them to develop their competence. This process can seem rather awkward and counter-intuitive to some instructors who typically approach course design by first selecting the content and materials, and then thinking about what they are going to do with lectures, labs and seminars. Understanding by Design asks course instructors to flip that thinking on its head – to start instead by defining what students will be able to do as a result of the course, then develop assessments, and finally build teaching and learning activities designed to support students in the successful completion of assessments and in their achievement of the course learning outcomes. Imagine how this approach to course design would influence your decisions for an experiential education course.

Backward design is based on the collaborative work of two US scholars, Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. Sadly, Dr. Grant Wiggins passed away in 2015, but during his career, he was a teacher of English and Philosophy, founder of Authentic Educator, the author of numerous books and articles, and an active columnist and social media contributor. Jay McTighe was the Director of the Maryland Assessment Consortium and served as a member of the National Assessment Forum. Like his close colleague, Grant Wiggins, McTighe was a prolific scholar and presented his work broadly. Both Wiggins and McTighe are well respected for their work curriculum, assessment and teaching design.

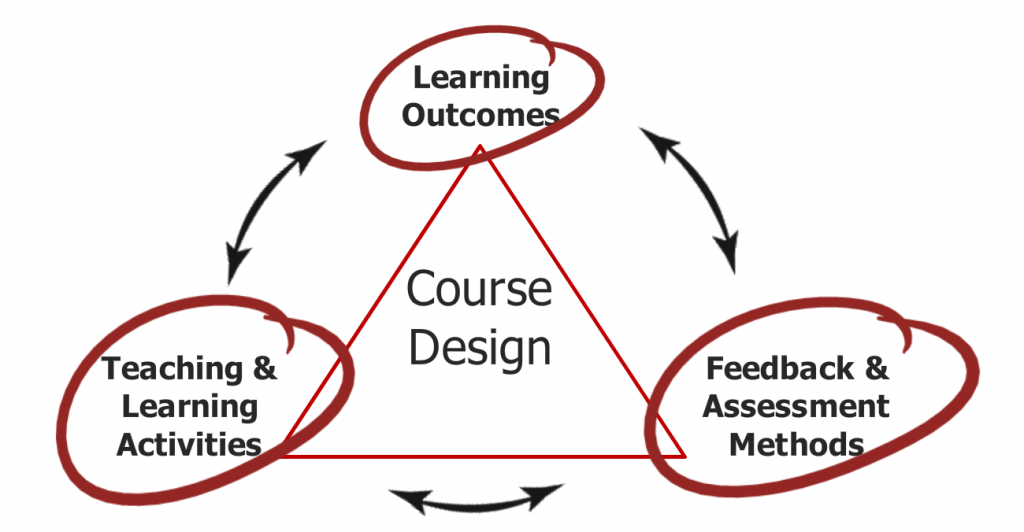

Constructive Alignment

Backward design principles also embrace the idea of constructive alignment in curriculum. John Biggs (see: Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of higher education, 1(1), 5-22.) first promoted the value of ensuring that the depth and breadth and complexity of an intended learning outcome is thoroughly defined, and that the ways in which students are assessed on that learning, and that the instructor works with the material, are all logically aligned. For example, in experiential education, an instructor may intend for the students to identify what it is they do and do not know how to do with ease and without reference to aids when completing a procedure. And so, authentic practice of a skill, under conditions of routine performance, becomes a really good way for students to assess their own capabilities. To consider this more concretely, consider how learning is developed when, for instance, allied health care students are provided with repeated opportunities to complete a client intake process, followed by structured reflection on how well they were able to follow recommended practice, where they have identified improvements in their own practice over time, where they felt the need to improvise, where they struggled and how they might address areas of uncertainty, or how they managed to respond to deviations from expectations in the moment. This repeated, direct experience, followed by engagement in a reflective exercises designed to help the students to think deeply and journal their impressions of their own knowledge and skill, will effectively accomplish the intended learning goals. As students repeat practice and engage in structured reflection tied to their achievement of defined learning outcomes, they can attend deeply to both specific or isolated aspects of performance, as well as the integration of what they have learned and how they are able to apply that knowledge in an increasingly nuanced and holistic way. Understanding by Design principles would also recommend that educators help students to consider the ways in which their learning would, or would not, usefully transfer over for application in other situations and contexts.

In order for any course, including an experiential course, to be constructively aligned, it is important to ensure that the degree of complexity and expectation for the learning outcomes, assessments and teaching and learning activities are at a consistent level. For example, if a learning outcome of an architectural drafting course is to ensure that a student can accurately interpret the symbols on blueprints to identify architectural structures and systems, then the most effective form of assessment might be to provide them with a blueprint and ask that they identify and explain the significance of the symbols that appear. This assessment would be particularly pertinent after the instructor had first modelled and then provided the students with independent, but assisted practice in completing this activity. It would not be as directly relevant to the learning outcomes to ask students to complete a multiple choice or matching exercise for symbols and their meaning out of the context of a blueprint and after merely reading a symbol chart in a textbook. Nor would it be effective to push students beyond the level of the intended learning outcome in an assessment by asking them to mark up a blank blueprint with the appropriate symbols and explain their meaning and purpose, all without instruction or practice on the assessed activity. As educators, as we design and deliver courses, it is really valuable for us to reflect continuously on what exactly we are hoping that students will be able to demonstrate, why and to what degree of sophistication. Having this clearly sorted out in our heads can really help us to create assessments, teaching approaches and learning activities that are connected well for our students.

In order for any course, including an experiential course, to be constructively aligned, it is important to ensure that the degree of complexity and expectation for the learning outcomes, assessments and teaching and learning activities are at a consistent level. For example, if a learning outcome of an architectural drafting course is to ensure that a student can accurately interpret the symbols on blueprints to identify architectural structures and systems, then the most effective form of assessment might be to provide them with a blueprint and ask that they identify and explain the significance of the symbols that appear. This assessment would be particularly pertinent after the instructor had first modelled and then provided the students with independent, but assisted practice in completing this activity. It would not be as directly relevant to the learning outcomes to ask students to complete a multiple choice or matching exercise for symbols and their meaning out of the context of a blueprint and after merely reading a symbol chart in a textbook. Nor would it be effective to push students beyond the level of the intended learning outcome in an assessment by asking them to mark up a blank blueprint with the appropriate symbols and explain their meaning and purpose, all without instruction or practice on the assessed activity. As educators, as we design and deliver courses, it is really valuable for us to reflect continuously on what exactly we are hoping that students will be able to demonstrate, why and to what degree of sophistication. Having this clearly sorted out in our heads can really help us to create assessments, teaching approaches and learning activities that are connected well for our students.

Another consequence of using design thinking in course planning is that it becomes easier to avoid aimless teaching and learning. The purpose of a course, and how it fits into the larger program curriculum, is clearer for the instructor and made more apparent to the students. Designing a course in this way does not preclude serendipitous discovery and learning for students, but it does direct their efforts intentionally toward important learning outcomes that need to be cultivated and helps them to make connections between theory and practice. Given the unique nature of experiential education opportunities, which are often undertaken offsite and involve partners, attention to course design becomes very important to ensure a meaningful learning experience for the students.

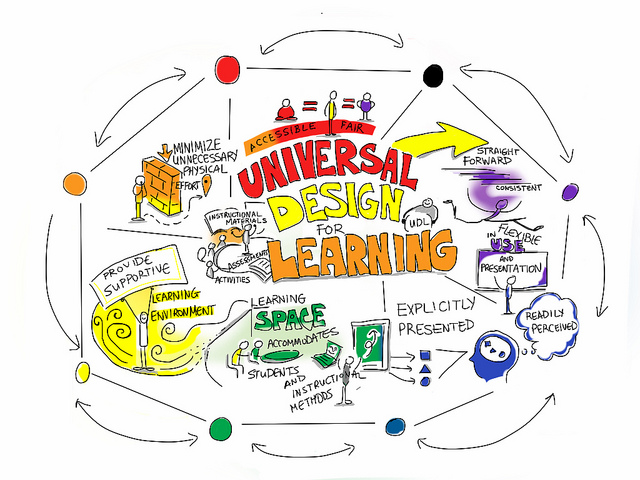

Universal Design for Learning

Ensuring meaningful learning experiences for students requires attention to designing courses for a diversity of learners. The CAST organization in the United States has developed a framework for inclusive course design that serves as a very useful resource for educators committed to supporting all students in becoming “purposeful and motivated; resourceful and knowledgeable; and strategic and goal directed.” (CAST. (n.d.).UDL: The UDL Guidelines. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org/). The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines provides educators with clear direction and examples of how to design courses that allow for multiple forms of engagement, representation, action and expression and are geared toward progressing from accessing, to building, and finally to internalizing options for designing learning opportunities that are effective and rich for all learners.

The UDL principles provide a well-conceived framework that you can use to inform your decisions about how to design a course that removes barriers and enables success for all learners, but the exigencies of course design for experiential education opportunities provoke creative thinking about how to apply UDL Principles effectively for internships, practicum, service-learning, co-operative education and other forms of experiential education. Next, let’s review the UDL framework from CAST and consider its application to course design in experiential education. How might attention to UDL principles influence your considerations about instructional modes and methods and the locations for student learning? How might it change the way that you assess the suitability of experiential learning opportunities and partnerships with industry, community service agencies or in remote locations?

Design: Alan Unwin,

Niagara College, Environmental Management

Design: Tim O’Connell,

Brock University, Outdoor Education

Tim O’Connell’s Outdoor education course outline