Chapter 9. Citations and Referencing

9.1 Supporting Your Ideas

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate when to use primary or secondary sources for support

- Explain the two forms of plagiarism and how to avoid them

- Explain the importance of academic integrity and the potential consequences of not abiding by this

In this chapter you are going to learn more about compiling references and citations. You will also learn strategies for handling some of the more challenging aspects of writing a research paper, such as integrating material from your sources, citing information correctly, and avoiding any misuse of your sources. The first section of this chapter will introduce you to broad concepts associated with adding support to your ideas and providing documentation—citations and references—when you use sources in your papers.

Using Primary and Secondary Research

As you write your draft, be mindful of how you are using primary and secondary source material to support your points. Recall that primary sources present firsthand information. Secondary sources are one step removed from primary sources. They present a writer’s analysis or interpretation of primary source materials. How you balance primary and secondary source material in your paper will depend on the topic and assignment.

Using Primary Sources Effectively

Some types of research papers must use primary sources extensively to achieve their purpose. Any paper that analyzes a primary text or presents the writer’s own experimental research falls in this category. Here are a few examples:

A paper for a literature course analyzing several poems by Emily Dickinson

A paper for a political science course comparing televised speeches delivered by two candidates for prime minister

A paper for a communications course discussing gender bias in television commercials

A paper for a business administration course that discusses the results of a survey the writer conducted with local businesses to gather information about their work from home and flextime policies

A paper for an elementary education course that discusses the results of an experiment the writer conducted to compare the effectiveness of two different methods of mathematics instruction

For these types of papers, primary research is the main focus. If you are writing about a work (including non-print works, such as a movie or a painting), it is crucial to gather information and ideas from the original work, rather than rely solely on others’ interpretations. And, of course, if you take the time to design and conduct your own field research, such as a survey, a series of interviews, or an experiment, you will want to discuss it in detail. For example, the interviews may provide interesting responses that you want to share with your reader.

Using Secondary Sources Effectively

For some assignments, it makes sense to rely more on secondary sources than primary sources. If you are not analyzing a text or conducting your own field research, you will need to use secondary sources extensively.

As much as possible, use secondary sources that are closely linked to primary research, such as a journal article presenting the results of the authors’ scientific study or a book that cites interviews and case studies. These sources are more reliable and add more value to your paper than sources that are further removed from primary research. For instance, a popular magazine article on junk food addiction might be several steps removed from the original scientific study on which it is loosely based. As a result, the article may distort, sensationalize, or misinterpret the scientists’ findings.

Even if your paper is largely based on primary sources, you may use secondary sources to develop your ideas. For instance, an analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s films would focus on the films themselves as a primary source, but might also cite commentary from critics. A paper that presents an original experiment would include some discussion of similar prior research in the field.

Jorge, who is preparing his essay on low-carbohydrate diets, knew he did not have the time, resources, or experience needed to conduct original experimental research for his paper. Because he was relying on secondary sources to support his ideas, he made a point of citing sources that were not far removed from primary research.

Tip

Some sources could be considered primary or secondary sources, depending on the writer’s purpose for using them. For instance, if a writer’s purpose is to inform readers about how the American No Child Left Behind legislation has affected elementary education in the United States, a Time magazine article on the subject would be a secondary source. However, suppose the writer’s purpose is to analyze how the news media has portrayed the effects of the No Child Left Behind legislation. In that case, articles about the legislation in news magazines like Time, Newsweek, and US News & World Report would be primary sources. They provide firsthand examples of the media coverage the writer is analyzing.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Your research paper presents your thinking about a topic, supported and developed by other people’s ideas and information. It is crucial to always distinguish between the two—as you conduct research, as you plan your paper, and as you write. Failure to do so can lead to plagiarism.

Intentional and Accidental Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the act of misrepresenting someone else’s work as your own. Sometimes a writer plagiarizes work on purpose—for instance, by copying and pasting or purchasing an essay from a website and submitting it as original course work. This often happens because the person has not managed his or her time and has left the paper to the last minute or has struggled with the writing process or the topic. Any of these can lead to desperation and cause the writer to just take someone else’s ideas and take credit for them.

In other cases, a writer may commit accidental plagiarism due to carelessness, haste, or misunderstanding. For instance, a writer may be unable to provide a complete, accurate citation because of neglecting to record bibliographical information. A writer may cut and paste a passage from a website into her paper and later forget where the material came from. A writer who procrastinates may rush through a draft, which easily leads to sloppy paraphrasing and inaccurate quotations. Any of these actions can create the appearance of plagiarism and lead to negative consequences.

Carefully organizing your time and notes is the best guard against these forms of plagiarism. Maintain a detailed working reference list and thorough notes throughout the research process. Check original sources again to clear up any uncertainties. Allow plenty of time for writing your draft so there is no temptation to cut corners.

To avoid unintentional/accidental plagiarism, follow these guidelines:

- Understand what types of information must be cited.

- Understand what constitutes fair dealing of a source.

- Keep source materials and notes carefully organized.

- Follow guidelines for summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting sources.

Academic Integrity

The concepts and strategies discussed in this section connect to a larger issue—academic integrity. You maintain your integrity as a member of an academic community by representing your work and others’ work honestly and by using other people’s work only in legitimately accepted ways. It is a point of honour taken seriously in every academic discipline and career field.

Academic integrity violations have serious educational and professional consequences. Even when cheating and plagiarism go undetected, they still result in a student’s failure to learn necessary research and writing skills. Students who are found guilty of academic integrity violations face consequences ranging from a failing grade to expulsion. Employees may be fired for plagiarism and do irreparable damage to their professional reputation. In short, it is never worth the risk.

9.2 Documenting Source Material

Learning Objectives

- Identify when to summarize, paraphrase, and directly quote information from research sources

- Identify when citations are needed

- Introduce sources

- Throughout the writing process, be scrupulous about documenting information taken from sources. The purpose of doing so is twofold:

- To give credit to other writers or researchers for their ideas

- To allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired

You will cite sources within the body of your paper and at the end of the paper in your references section. For this assignment, you will use the citation format used by the American Psychological Association (also known as APA style). Within this course and for all of your courses at JIBC, you will need to follow the JIBC APA Reference Guide when formatting citations and references within your papers.

This section covers the nitty-gritty details of in-text citations. You will learn how to format citations for different types of source materials, whether you are citing brief quotations, paraphrasing ideas, or quoting longer passages. You will also learn techniques you can use to introduce quoted and paraphrased material effectively. Keep this section handy as a reference to consult while writing the body of your paper.

Formatting Cited Material: The Basics

In-text citations usually provide the name of the author(s) and the year the source was published. For direct quotations, the page number must also be included. Use past tense verbs when introducing a quote: for example, “Smith found…,” not “Smith finds.…”

Citing Sources in the Body of Your Paper

In-text citations document your sources within the body of your paper. These include two vital pieces of information: the author’s name and the year the source material was published. When quoting a print source, also include in the citation the page number where the quoted material originally appears. The page number follows the year in the in-text citation. Page numbers are necessary only when content has been directly quoted, not when it has been summarized or paraphrased.

Using Source Material in Your Paper

One of the challenges of writing a research paper is successfully integrating your ideas with material from your sources. Your paper must explain what you think, or it will read like a disconnected string of facts and quotations. However, you also need to support your ideas with research, or they will seem insubstantial. How do you strike the right balance?

In your essay, the introduction and conclusion function like the frame around a picture. They define and limit your topic and place your research in context. In the body paragraphs of your paper, you need to integrate ideas carefully at the paragraph level and at the sentence level. You will use topic sentences in your paragraphs to make sure readers understand the significance of any facts, details, or quotations you cite. You will also include sentences that transition between ideas from your research, either within a paragraph or between paragraphs. At the sentence level, you will need to think carefully about how you introduce paraphrased and quoted material.

Earlier you learned about summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting when taking notes. In the next few sections, you will learn how to use these techniques in the body of your paper to weave in source material to support your ideas.

Summarizing Sources

Look back at Section 3.2: Summarizing to refresh your memory of how Jorge summarized the article. As was mentioned there, when you are summarizing, you are focusing on identifying and sharing the main elements of a source. This is when you paraphrase the concepts and put them in your own words, demonstrating you have a firm understanding of the concepts presented and are able to incorporate them into your own paper.

Within a paragraph, this information may appear as part of your introduction to the material or as a parenthetical citation at the end of a sentence. Read the examples that follow.

Summary

Leibowitz (2008) found that low-carbohydrate diets often helped subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood sugar levels.

The introduction to the source material (the attributive tag) includes the author’s name followed by the year of publication in parentheses.

Summary

Low-carbohydrate diets often help subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood sugar levels (Leibowitz, 2008).

The parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence includes the author’s name, a comma, and the year the source was published. The period at the end of the sentence comes after the parentheses.

Formatting Paraphrased and Summarized Material

When you paraphrase or summarize ideas from a source, you follow the same guidelines previously provided, except that you are not required to provide the page number where the ideas are located. If you are summing up the main findings of a research article, simply providing the author’s name and publication year may suffice, but if you are paraphrasing a more specific idea, consider including the page number.

Read the following examples.

Chang (2008) pointed out that weight-bearing exercise has many potential benefits for women.

Here, the writer is summarizing a major idea that recurs throughout the source material. No page reference is needed.

Chang (2008) found that weight-bearing exercise could help women maintain or even increase bone density through middle age and beyond, reducing the likelihood that they will develop osteoporosis in later life (p. 86).

Although the writer is not directly quoting the source, this passage paraphrases a specific detail, so the writer chose to include the page number where the information is located.

Introducing Cited Material Effectively

Including an introductory phrase in your text, such as “Jackson wrote” or “Copeland found,” often helps you integrate source material smoothly. This citation technique also helps convey that you are actively engaged with your source material. Unfortunately, during the process of writing your research paper, it is easy to fall into a rut and use the same few dull verbs repeatedly, such as “Jones said,” “Smith stated,” and so on.

Punch up your writing by using strong verbs that help your reader understand how the source material presents ideas. There is a world of difference between an author who “suggests” and one who “claims,” one who “questions” and one who “criticizes.” You do not need to consult your thesaurus every time you cite a source, but do think about which verbs will accurately represent the ideas and make your writing more engaging. Table 9.1 Strong Verbs for Introducing Cited Material shows some possibilities.

Table 9.1 Strong Verbs for Introducing Cited Material

| ask | suggest | question | recommend | determine | insist |

| explain | assert | claim | hypothesize | measure | argue |

| propose | compare | contrast | evaluate | conclude | find |

| study | sum up | believe | warn | point out | assess |

When to Cite

Any idea or fact taken from an outside source must be cited, in both the body of your paper and the references. The only exceptions are facts or general statements that are common knowledge. Common knowledge facts or general statements are commonly supported by and found in multiple sources. For example, a writer would not need to cite the statement that most breads, pastas, and cereals are high in carbohydrates; this is well known and well documented. However, if a writer explained in detail the differences among the chemical structures of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, a citation would be necessary. When in doubt, cite!

Fair Dealing

In recent years, issues related to the fair use of sources have been prevalent in popular culture. Recording artists, for example, may disagree about the extent to which one has the right to sample another’s music. For academic purposes, however, the guidelines for fair dealing are reasonably straightforward.

Writers may quote from or paraphrase material from previously published works without formally obtaining the copyright holder’s permission. Fair dealing in copyright law allows a writer to legitimately use brief excerpts from source material to support and develop his or her own ideas. For instance, a columnist may excerpt a few sentences from a novel when writing a book review. However, quoting or paraphrasing another’s work excessively, to the extent that large sections of the writing are unoriginal, is not fair dealing.

As he worked on his draft, Jorge was careful to cite his sources correctly and not to rely excessively on any one source. Occasionally, however, he caught himself quoting a source at great length. In those instances, he highlighted the paragraph in question so that he could go back to it later and revise. Read the example, along with Jorge’s revision.

Summary

Heinz (2009) found that “subjects in the low-carbohydrate group (30% carbohydrates; 40% protein, 30% fat) had a mean weight loss of 10 kg (22 lbs) over a four-month period.” These results were “noticeably better than results for subjects on a low-fat diet (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat)” whose average weight loss was only “7 kg (15.4 lbs) in the same period.” From this, it can be concluded that “low-carbohydrate diets obtain more rapid results.” Other researchers agree that “at least in the short term, patients following low-carbohydrate diets enjoy greater success” than those who follow alternative plans (Johnson & Crowe, 2010).

Self-Practice EXERCISE 9.1

Paraphrasing practice is always a good thing! Take a look at Jorge’s “summary” above. Notice he is not really summarizing but rather quoting. While this is technically not plagiarism, it does not show any processing of the information from the original source. It is just copying and pasting; the end result seems very choppy, and a lot of the information can be generalized.

For this exercise, try to rewrite Jorge’s summary in your own words.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

After reviewing the paragraph, Jorge realized that he had drifted into unoriginal writing. Most of the paragraph was taken verbatim from a single article. Although Jorge had enclosed the material in quotation marks, he knew it was not an appropriate way to use the research in his paper.

Summary

Low-carbohydrate diets may indeed be superior to other diet plans for short-term weight loss. In a study comparing low-carbohydrate diets and low-fat diets, Heinz (2009) found that subjects who followed a low-carbohydrate plan (30% of total calories) for four months lost, on average, about 3 kilograms more than subjects who followed a low-fat diet for the same time. Heinz concluded that these plans yield quick results, an idea supported by a similar study conducted by Johnson and Crowe (2010). What remains to be seen, however, is whether this initial success can be sustained for longer periods.

As Jorge revised the paragraph, he realized he did not need to quote these sources directly. Instead, he paraphrased their most important findings. He also made sure to include a topic sentence stating the main idea of the paragraph and a concluding sentence that transitioned to the next major topic in his essay.

Tip

It is extremely important to remember that even though you are summarizing and paraphrasing from another source—not quoting—you must still include a citation, including the last name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

Example

Additionally, marijuana burning creates toxins; this strategy is counterproductive, and there are numerous individual hazards associated with using the plant as medicine (Ogborne, Smart, & Adlaf, 2000).

Example taken from:

Writing Commons. (2014, September). Open Text.Retrieved from http://writingcommons.org/format/apa/675-block-quotations-apa

Writing at Work

It is important to accurately represent a colleague’s ideas or communications in the workplace. When writing professional or academic papers, be mindful of how the words you use to describe someone’s tone or ideas carry certain connotations. Do not say a source “argues” a particular point unless an argument is, in fact, presented. Use lively language, but avoid language that is emotionally charged. Doing so will ensure you have represented your colleague’s words in an authentic and accurate way.

Key Takeaways

- An effective research paper focuses on the writer’s ideas. The introduction and conclusion present and revisit the writer’s thesis. The body of the paper develops the thesis and related points with information from research.

- Ideas and information taken from outside sources must be cited in the body of the paper and in the references section.

- Material taken from sources should be used to develop the writer’s ideas. Summarizing and paraphrasing are usually most effective for this purpose.

- A summary concisely restates the main ideas of a source in the writer’s own words.

- A paraphrase restates ideas from a source using the writer’s own words and sentence structures.

- Direct quotations should be used sparingly. Ellipses and brackets must be used to indicate words that are omitted or changed for conciseness or grammatical correctness.

- Always represent material from outside sources accurately.

- Plagiarism has serious academic and professional consequences. To avoid accidental plagiarism, keep research materials organized, understand guidelines for fair dealing and appropriate citation of sources, and review the paper to make sure these guidelines are followed.

9.3 Making Your Quotes Fit

Learning Objectives

- Apply guidelines for citing sources within the body of the paper

- Evaluating when to use a short or long quote

- Incorporate short quotes with correct APA formatting

- Incorporate long quotations with correct APA formatting

So, now you may have decided after much critical thought, that you definitely have found the most amazing, well-suited quote that cannot be paraphrased, and you want to incorporate that quote into your paper. There are different ways to do this depending on how long the quote is; there are also a number of formatting requirements you need to apply.

Quoting Sources Directly

Most of the time, you will summarize or paraphrase source material instead of quoting directly. Doing so shows that you understand your research well enough to write about it confidently in your own words. However, direct quotes can be powerful when used sparingly and with purpose.

Quoting directly can sometimes help you make a point in a colourful way. If an author’s words are especially vivid, memorable, or well phrased, quoting them may help hold your reader’s interest. Direct quotations from an interviewee or an eyewitness may help you personalize an issue for readers. Also, when you analyze primary sources, such as a historical speech or a work of literature, quoting extensively is often necessary to illustrate your points. These are valid reasons to use quotations.

Less-experienced writers, however, sometimes overuse direct quotations in a research paper because it seems easier than paraphrasing. At best, this reduces the effectiveness of the quotations. At worst, it results in a paper that seems haphazardly pasted together from outside sources. Use quotations sparingly for greater impact.

When you do choose to quote directly from a source, follow these guidelines:

Only use a quote when the original writer has phrased a statement so perfectly that you do not believe you could rephrase it any better without getting away from the writer’s point.

Make sure you have transcribed the original statement accurately.

Represent the author’s ideas honestly. Quote enough of the original text to reflect the author’s point accurately.

Use an attributive tag (e.g., “According to Marshall (2013)….”) to lead into the quote and provide a citation at the same time.

Never use a standalone quotation. Always integrate the quoted material into your own sentence.

Make sure any omissions or changed words do not alter the meaning of the original text. Omit or replace words only when absolutely necessary to shorten the text or to make it grammatically correct within your sentence.

Use ellipses (3) […] if you need to omit a word or phrase; use (4) [….] when you are removing a section—maybe a complete sentence—that would end in a period. This shows your reader that you have critically and thoroughly examined the contents of this quote and have chosen only the most important and relevant information.

Use brackets [ ] if you need to replace a word or phrase or if you need to change the verb tense.

Use [sic] after something in the quote that is grammatically incorrect or spelled incorrectly. This shows your reader that the mistake is in the original, not your writing.

Use double quotation marks [“ ”] when quoting and use single quotation marks [‘ ’] when you include a quote within a quote (i.e., if you quote a passage that already includes a quote, you need to change the double quotation marks in the original to single marks, and add double quotations marks around your entire quote).

Remember to include correctly formatted citations that follow the JIBC APA Reference Guide.

Jorge interviewed a dietitian as part of his research, and he decided to quote her words in his paper. Read an excerpt from the interview and Jorge’s use of it, which follows.

Source

Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype about low-carbohydrate miracle diets like Atkins and so on. Sure, for some people, they are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.

Summary

Registered dietitian Dana Kwon (2010) admits, “Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype.… Sure, for some people, [low carbohydrate diets] are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.”

Notice how Jorge smoothly integrated the quoted material by starting the sentence with an introductory phrase. His use of an ellipsis and brackets did not change the source’s meaning.

Short versus Long Quotations

Remember, what you write in essays should be primarily your own words; your instructors want to know what your ideas are and for you to demonstrate your own critical thinking. This means you should only use the ideas of experts in the form of quotes to support your ideas. A paper that consists of mostly quotes pieced together does not demonstrate original thought but rather that you are good at cutting and pasting. Therefore, you should strive to state your ideas, develop them thoroughly, and then insert a supporting quote, and only if necessary. Focus on paraphrasing and integrating and blending those external sources into your own ideas (giving the original author credit by using a citation, of course). When deciding to use any quotation as opposed to paraphrasing, you need to make sure the quote is a statement that the original author has worded so beautifully it would be less effective if you changed it into your own words. When you find something you would like to include verbatim (word for word) from a source, you need to decide if you should include the whole paragraph or section, or a smaller part. Sometimes, you may choose to use a longer quote but remove any unnecessary words. You would then use ellipses to show what content you have removed. The following examples show how this is done.

Original

According to Marshall (2010), “Before the creation of organized governmental policing agencies, it was citizens possessing firearms who monitored and maintained the peace” (p. 712).

With Ellipses

According to Marshall (2010), “Before the creation of organized governmental policing agencies, … citizens possessing firearms … monitored and maintained the peace” (p. 712).

Short Quotations

A short quote can be as one word or a phrase or a complete sentence as long as three lines of text (again, removing any unnecessary words). Generally, a short quotation is one that is fewer than 40 words. Whether you use a complete sentence or only part of one, you need to make sure it blends in perfectly with your own sentence or paragraph. For example, if your paragraph is written in the present tense but the quote is in the past, you will need to change the verb, so it will fit into your writing. (You will read about on this shortly.) Using an attributive tag is another way to help incorporate your quote more fluidly. An attributive tag is a phrase that shows your reader you got the information from a source, and you are giving the author attribution or credit for his or her ideas or words. Using an attributive tag allows you to provide a citation at the same time as helping integrate the quote more smoothly into your work.

Example

According to Marshall (2010), “Before the creation of organized governmental policing agencies, it was citizens possessing firearms who monitored and maintained the peace” (p. 712).

In the example above, the attributive tag (with citation) is underlined; this statement is giving Marshall credit for his own words and ideas. You should note that this short quotation is a complete sentence taken from Marshall’s bigger document, which is why the first word, Before, is capitalized. If you were to include only a portion of that sentence, perhaps excerpting from the middle of it, you would not start the quote with a capital.

Example

Marshall (2010) argues that vigilantism in the Wild West was committed by “citizens possessing firearms who monitored and maintained the peace” (p. 712).

In this example, notice how the student has only used a portion of the sentence, so did not need to include the capital.

Tip

If you do not use an attributive tag because the quote already fits smoothly into your sentence, you need to include the author’s name after the sentence in parentheses with the date and page number.

Example

Vigilantism in the Wild West was committed by “citizens possessing firearms who monitored and maintained the peace” (Marshall, 2010, p. 712).

Formatting Short Quotations

For short quotations, use quotation marks to indicate where the quoted material begins and ends, and cite the name of the author(s), the year of publication, and the page number where the quotation appears in your source. Remember to include commas to separate elements within the parenthetical citation. Also, avoid redundancy. If you name the author(s) in your sentence, do not repeat the name(s) in your parenthetical citation. Review following the examples of different ways to cite direct quotations.

Chang (2008) emphasized that “engaging in weight-bearing exercise consistently is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (p. 49).

The author’s name can be included in the body of the sentence or in the parenthetical citation. Note that when a parenthetical citation appears at the end of the sentence, it comes after the closing quotation marks and before the period. The elements within parentheses are separated by commas.

Weight Training for Women (Chang, 2008) claimed that “engaging in weight-bearing exercise consistently is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (p. 49).

Weight Training for Women claimed that “engaging in weight-bearing exercise consistently is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (Chang, 2008, p. 49).

Including the title of a source is optional.

In Chang’s 2008 text Weight Training for Women, she asserts, “Engaging in weight-bearing exercise is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (p. 49).

The author’s name, the date, and the title may appear in the body of the text. Include the page number in the parenthetical citation. Also, notice the use of the verb asserts to introduce the direct quotation.

“Engaging in weight-bearing exercise,” Chang asserts, “is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (2008, p. 49).

You may begin a sentence with the direct quotation and add the author’s name and a strong verb before continuing the quotation.

Tip

Although APA style guidelines do not require writers to provide page numbers for material that is not directly quoted, your instructor may wish you to do so when possible. Check with your instructor about his or her preferences.

Long (Block) Quotations

Long quotations should be used even more sparingly than shorter ones. Long quotations can range in length from four to seven or eight lines (40 words or more, and should never be as long as a page. There are two reasons for this: First, by using a long quote, you are essentially letting the original author do all the thinking for you; remember that your audience wants to see your ideas, not someone else’s. Second, unless all the information and every word in the long quote is essential and could not be paraphrased (which is highly doubtful with a long passage), you are not showing your audience you have processed or evaluated the importance of the source’s critical information and weeded out the unnecessary information. If you believe you have found the perfect paragraph to support your ideas, and you decide you really want or need to use the long quote, see if you can shorten it by removing unnecessary words or complete sentences and put ellipses in their place. This will again show your reader that you have put a lot of thought into the use of the quote and that you have included it just because you did not want to do any thinking.

Tip

Be wary of quoting from sources at length. Remember, your ideas should drive the paper, and quotations should be used to support and enhance your points. Make sure any lengthy quotations that you include serve a clear purpose. Generally, no more than 10 to 15 percent of a paper should consist of quoted material.

Long Quotations: How to Make Them Fit

As with short quotations, you need to make sure long quotations fit into your writing. To introduce a long quote, you need to include a stem (this can include an attributive tag) followed by a colon (:). The stem is underlined in the example below.

Example:

Marshall uses the example of towns in the Wild West to explain that:

Much of the population—especially younger males—frequently engaged in violence by participating in saloon fights and shootouts and gun fights. [However,] crimes committed by females, the elderly, or the infirm were rare occasions were much rarer because of those individuals being less likely to frequent such drinking establishments. (2010, p. 725)

In example, you can see the stem clearly introduces the quote in a grammatically correct way, leading into the quote fluidly.

Formatting Longer Quotations

When you quote a longer passage from a source—40 words or more—you need to use a different format to set off the quoted material. Instead of using quotation marks, create a block quotation by starting the quotation on a new line and indented five spaces from the margin. Note that in this case, the parenthetical citation comes after the period that ends the sentence. If the passage continues into a second paragraph, indent a full tab (five spaces) again in the first line of the second paragraph. Here is an example:

In recent years, many writers within the fitness industry have emphasized the ways in which women can benefit from weight-bearing exercise, such as weightlifting, karate, dancing, stair climbing, hiking, and jogging. Chang (2008) found that engaging in weight-bearing exercise regularly significantly reduces women’s risk of developing osteoporosis. Additionally, these exercises help women maintain muscle mass and overall strength, and many common forms of weight bearing exercise, such as brisk walking or stair climbing, also provide noticeable cardiovascular benefits.

It is important to note that swimming cannot be considered a weight-bearing exercise, since the water supports and cushions the swimmer. That doesn’t mean swimming isn’t great exercise, but it should be considered one part of an integrated fitness program. (p. 93)

Self-Practice EXERCISE 9.2

Look at the longblock quotation example above. Identify four differences between how it is formatted and how you would format a short quotation.

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

Tip

To format a long quote, you need to remember the following:

You may want to single space the quote, but not the main part of your essay. This will allow the long block quotation to stand out even more.

Indent on both sides of the quote; you can use left or full justification.

Do not use quotation marks; they are unnecessary because the spacing and indenting (and citation) will tell your reader this is a quote.

Do not put the quote in italics.

Include the end period (.) before the citation. See the example above.

9.4 Citation Guidelines

Learning Objectives

- Apply APA guidelines for citing sources within the body of the paper for various source types

In-Text Citations

Throughout the body of your paper, you must include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. The purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; you will provide more detailed information for each source you cite in text in the references section. (Refer to your JIBC APA Reference Guide for guidance on compose citation—for quotes or paraphrasing—under the referencing example for each type of source.)

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, you must include the page number where the quote appears in the work being cited. This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that in this example the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can use the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually straightforward. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews.

Self-Practice EXERCISE 9.3

In each of the sentences below, identify the mistakes with how the quote was incorporated. Look carefully; some of them are tricky and have more than one error.

One researcher outlines the viewpoints of both parties:

Freedom of research is undoubtedly a cherished ideal in our society. In that respect, research has an interest in being free, independent, and unrestricted. Such interests weigh against regulations. On the other hand, research should also be valid, verifiable, and unbiased, to attain the overarching goal of gaining obtaining generalisable knowledge (Simonsen, 2012, p. 46).

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

2.

According to a recent research study, ‘that women aged 41 and over were 5 times less likely to use condoms than were men aged 18 and younger’ (2007, p. 707).

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

3.

According to Emlet, the rate in which older adults have contracted HIV has grown exponentially. Currently, “approximately 20% of all HIV cases were among older adults”. (Emlet, 2008).

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

Examples taken from:

Writing Commons. (2014, September). Open Text. Retrieved from http://writingcommons.org/format/apa/675-block-quotations-apa

Answers

1.

The quote is not indented on either side.

[sic] is required after “obtaining”because it is a mistake in the original.

The period is placed after the citation not before.

2.

“That” should have been removed to make the quote flow with the rest of the sentence.

There is no attributive tag and no mention of the authors in the citation: Sormanti & Shibusawa

Single quotation marks are used instead of double quotation marks.

3.

The writer used an attributive tag with the name of the source’s author, then gave the name again in the citation at the end. The second one is redundant.

The original quote used the past tense (“were”), but the transition word “currently” requires this verb to be changed to present tense (“are”) inside square brackets to make it fit.

There is an extra period before the citation. With a short quote, you put the end punctuation after the citation.

Formatting In-Text Citations

The following subsections discuss the correct format for various types of in-text citations. Read them through quickly to get a sense of what is covered, and then refer to them again as needed.

Print Sources

This section covers books, articles, and other print sources with one or more authors.

A Work by One Author

For a print work with one author, follow the guidelines provided in the JIBC APA Reference Guide. Always include the author’s name and year of publication. Include a page reference whenever you quote a source directly. (See also the guidelines presented earlier in this chapter about when to include a page reference for paraphrased material.)

Chang (2008) emphasized that “engaging in weight-bearing exercise consistently is one of the single best things women can do to maintain good health” (p. 49).

Chang (2008) pointed out that weight-bearing exercise has many potential benefits for women.

Two or More Works by the Same Author

At times, your research may include multiple works by the same author. If the works were published in different years, a standard in-text citation will serve to distinguish them. If you are citing multiple works by the same author published in the same year, include a lowercase letter immediately after the year. Rank the sources in the order they appear in your references section. The source listed first should include an a after the year, the source listed second should include a b, and so on.

Rodriguez (2009a) criticized the nutrition supplement industry for making unsubstantiated and sometimes misleading claims about the benefits of taking supplements. Additionally, he warned that consumers frequently do not realize the potential harmful effects of some popular supplements (Rodriguez, 2009b).

The author’s last name is again mentioned in the final citation despite it being used in the attributive tag. In this case, this is acceptable because this is referring to a different source written by the same person.

Works by Authors with the Same Last Name

If you are citing works by different authors with the same last name, include each author’s initials in your citation, whether you mention them in the text or in parentheses. Do so even if the publication years are different.

J. S. Williams (2007) believes nutritional supplements can be a useful part of some diet and fitness regimens. C. D. Williams (2008), however, believes these supplements are overrated.

According to two leading researchers, the rate of childhood obesity exceeds the rate of adult obesity (K. Connelley, 2010; O. Connelley, 2010).

Studies from both A. Wright (2007) and C. A. Wright (2008) confirm the benefits of diet and exercise on weight loss.

A Work by Two Authors

When two authors are listed for a given work, include both authors’ names each time you cite the work. If you are citing their names in parentheses, use an ampersand (&) between them. (Use the word and, however, if the names appear in your sentence.)

As Garrison and Gould (2010) pointed out, “It is never too late to quit smoking. The health risks associated with this habit begin to decrease soon after a smoker quits” (p. 101).

As doctors continue to point out, “It is never too late to quit smoking. The health risks associated with this habit begin to decrease soon after a smoker quits” (Garrison & Gould, 2010, p. 101).

A Work by Three to Five Authors

If the work you are citing has three to five authors, list all the authors’ names the first time you cite the source. In subsequent citations, use the first author’s name followed by the abbreviation et al. (Et al. is short for et alia, the Latin phrase for “and others.”)

Henderson, Davidian, and Degler (2010) surveyed 350 smokers aged 18 to 30.

One survey, conducted among 350 smokers aged 18 to 30, included a detailed questionnaire about participants’ motivations for smoking (Henderson, Davidian, & Degler, 2010).

Note that these examples follow the same ampersand conventions as sources with two authors. Again, use the ampersand only when listing authors’ names in parentheses.

As Henderson et al. (2010) found, some young people, particularly young women, use smoking as a means of appetite suppression.

Disturbingly, some young women use smoking as a means of appetite suppression (Henderson et al., 2010).

Note how the phrase et al. is punctuated. There is no period comes after et, but there is one with al. because it is an abbreviation for a longer Latin word. In parenthetical references, include a comma after et al. but not before. Remember this rule by mentally translating the citation to English: “Henderson and others, 2010.”

A Work by Six or More Authors

If the work you are citing has six or more authors, list only the first author’s name, followed by et al., in your in-text citations. The other authors’ names will be listed in your references section.

Researchers have found that outreach work with young people has helped reduce tobacco use in some communities (Costello et al., 2007).

A Work Authored by an Organization

When citing a work that has no individual author but is published by an organization, use the organization’s name in place of the author’s name. Lengthy organization names with well-known abbreviations can be abbreviated. In your first citation, use the full name, followed by the abbreviation in square brackets. Subsequent citations may use the abbreviation only.

It is possible for a patient to have a small stroke without even realizing it (American Heart Association [AHA], 2010).

Another cause for concern is that even if patients realize that they have had a stroke and need medical attention, they may not know which nearby facilities are best equipped to treat them (AHA, 2010).

A Work with No Listed Author

If no author is listed and the source cannot be attributed to an organization, use the title in place of the author’s name. You may use the full title in your sentence or use the first few words—enough to convey the key ideas—in a parenthetical reference. Follow standard conventions for using italics or quotations marks with titles:

Use italics for titles of books or reports.

Use quotation marks for titles of articles or chapters.

“Living With Diabetes: Managing Your Health” (2009) recommends regular exercise for patients with diabetes.

Regular exercise can benefit patients with diabetes (“Living with Diabetes,” 2009).

A Work Cited within Another Work

To cite a source that is referred to within another secondary source, name the first source in your sentence. Then, in parentheses, use the phrase as cited in and the name of the second source author.

Rosenhan’s study “On Being Sane in Insane Places” (as cited in Spitzer, 1975) found that psychiatrists diagnosed schizophrenia in people who claimed to be experiencing hallucinations and sought treatment—even though these patients were, in fact, imposters.

Two or More Works Cited in One Reference

At times, you may provide more than one citation in a parenthetical reference, such as when you are discussing related works or studies with similar results. List the citations in the same order they appear in your references section, and separate the citations with a semicolon.

Some researchers have found serious flaws in the way Rosenhan’s study was conducted (Dawes, 2001; Spitzer, 1975).

Both of these researchers authored works that support the point being made in this sentence, so it makes sense to include both in the same citation.

A Famous Text Published in Multiple Editions

In some cases, you may need to cite an extremely well-known work that has been repeatedly republished or translated. Many works of literature and sacred texts, as well as some classic nonfiction texts, fall into this category. For these works, the original date of publication may be unavailable. If so, include the year of publication or translation for your edition. Refer to specific parts or chapters if you need to cite a specific section. Discuss with your instructor whether he or she would like you to cite page numbers in this particular instance.

In New Introductory Lectures on Psycho Analysis, Freud explains that the “manifest content” of a dream—what literally takes place—is separate from its “latent content,” or hidden meaning (trans. 1965, lecture XXIX).

In this example, the student is citing a classic work of psychology, originally written in German and later translated to English. Since the book is a collection of Freud’s lectures, the student cites the lecture number rather than a page number.

An Introduction, Foreword, Preface, or Afterword

To cite an introduction, foreword, preface, or afterword, cite the author of the material and the year, following the same format used for other print materials.

Electronic Sources

Whenever possible, cite electronic sources as you would print sources, using the author, the date, and where appropriate, a page number. For some types of electronic sources—for instance, many online articles—this information is easily available. Other times, however, you will need to vary the format to reflect the differences in online media.

Online Sources without Page Numbers

If an online source has no page numbers but you want to refer to a specific portion of the source, try to locate other information you can use to direct your reader to the information cited. Some websites number paragraphs within published articles; if so, include the paragraph number in your citation. Precede the paragraph number with the abbreviation for the word paragraph and the number of the paragraph (e.g., para. 4).

As researchers have explained, “Incorporating fresh fruits and vegetables into one’s diet can be a challenge for residents of areas where there are few or no easily accessible supermarkets” (Smith & Jones, 2006, para. 4).

Even if a source does not have numbered paragraphs, it is likely to have headings that organize the content. In your citation, name the section where your cited information appears, followed by a paragraph number.

The American Lung Association (2010) noted, “After smoking, radon exposure is the second most common cause of lung cancer” (What Causes Lung Cancer? section, para. 2).

This student cited the appropriate section heading within the website and then counted to find the specific paragraph where the cited information was located.

If an online source has no listed author and no date, use the source title and the abbreviation n.d. in your parenthetical reference.

It has been suggested that electromagnetic radiation from cellular telephones may pose a risk for developing certain cancers (“Cell Phones and Cancer,” n.d.).

Personal Communication

For personal communications, such as interviews, letters, and emails, cite the name of the person involved, clarify that the material is from a personal communication, and provide the specific date the communication took place. Note that while in-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, personal communications are an exception to this rule. They are cited only in the body text of your paper.

J. H. Yardley, M.D., believes that available information on the relationship between cell phone use and cancer is inconclusive (personal communication, May 1, 2009).

Writing at Work

At work, you may sometimes share information resources with your colleagues by photocopying an interesting article or forwarding the URL of a useful website. Your goal in these situations and in formal research citations is the same: to provide enough information to help your professional peers locate and follow up on potentially useful information. Provide as much specific information as possible to achieve that goal, and consult with your supervisor or professor as to what specific style he or she may prefer.

Key Takeaways

- In APA papers, in-text citations include the name of the author(s) and the year of publication whenever possible.

- Page numbers are always included when citing quotations. It is optional to include page numbers when citing paraphrased material; however, this should be done when citing a specific portion of a work.

- When citing online sources, provide the same information used for print sources if it is available.

- When a source does not provide information that usually appears in a citation, in-text citations should provide readers with alternative information that would help them locate the source material. This may include the title of the source, section headings and paragraph numbers for websites, and so forth.

- When writing a paper, discuss with your instructor what particular standards you should follow.

9.5 Creating a References Page

Learning Objectives

- Navigate and find examples of references in the JIBC APA Reference Guide

- Compose an APA-formatted references page

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive information, which allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

In-text citations are necessary within your writing to show where you have borrowed ideas or quoted directly from another author. These are kept short because you do not want to disrupt the flow of your writing and distract the reader. While the in-text citation is very important, it is not enough to enable yourreaders to locate that source if they would like to use it for their own research.

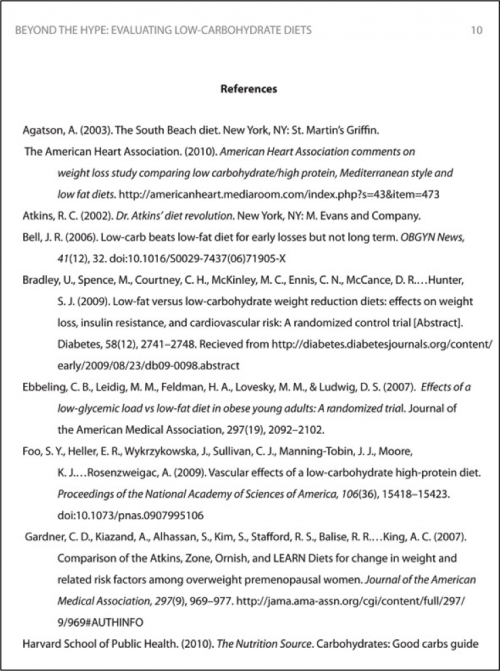

The references section of your essay may consist of a single page for a brief research paper or may extend for many pages in professional journal articles. This section provides detailed information about how to create the references section of your paper. You will review basic formatting guidelines and learn how to format bibliographical entries for various types of sources. As you create this section of your paper, follow the guidelines provided here.

Formatting the References Page

To set up your references section, use the insert page break feature of your word processing program to begin a new page. Note that the header and margins will be the same as in the body of your paper, and pagination will continue from the body of your paper. (In other words, if you set up the body of your paper correctly, the correct header and page number should appear automatically in your references section.) The references page should be double spaced and list entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces, or one tab space; this is called a “hanging indent.”

What to Include in the References Section

Generally, the information to include in your references section is:

The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

The full title of the source

For books, the city of publication

For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

Before you start compiling your own references and translating referencing information from possibly other styles into APA style, you need to be able to identify each piece of information in the reference. This can sometimes be challenging because the different styles format the information differently and may put it in different places within the reference. However, the types of information each of the referencing styles requires is generally the same.

Navigating Your Reference Guide

The JIBC APA Reference Guide is organized into types of sources—print, online, mixed media—and by number of authors (or if there is no author). Once you find the referencing format you need in the guide, you can study the example and follow the structure to set up your own citations. (The style guide also provides examples for how to do the in-text citation for quotes and paraphrasing from that type of source.)

You may be asking yourself why you cannot just use the reference that is often provided on the first page of the source (like a journal article), but you need to remember that not all authors use APA style referencing, or even if they do, they may not use the exact formatting you need to follow.

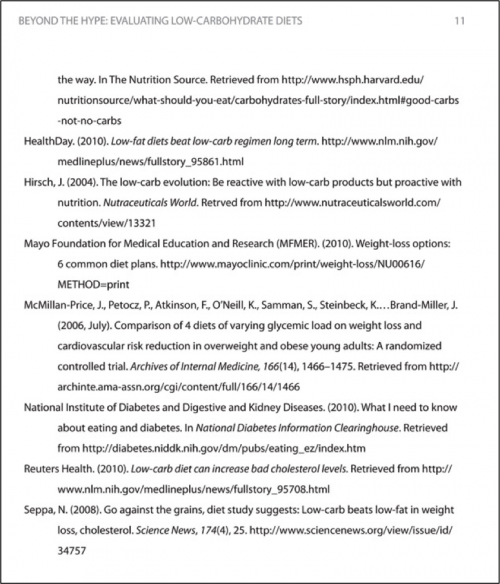

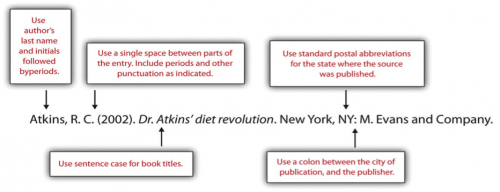

Putting together a references page becomes a lot easier once you recognize the types of information you continually see in references. For example, anytime you see something italicized for APA or underlined (in MLA), you know it is the title of the major piece of writing, such as a book with chapters or an academic journal with multiple articles. Take a look at the examples below.

Sample Book Entry

Sample Journal Article Entry

Tip

If you are sourcing a chapter from a book, do not italicize the title of the chapter; instead, use double quotes. You also need to include the pages of the chapter within the book. (You do italicize the title of the book, similar to the journal article example above.)

The following box provides general guidelines for formatting the reference page. For the remainder of this chapter, you will learn about how to format reference entries for different source types, including multi-author and electronic sources.

Formatting the References Section: APA General Guidelines

Include the heading References, centred at the top of the page. The heading should not be boldfaced, italicized, or underlined.

Use double-spaced type throughout the references section, as in the body of your paper.

Use hanging indentation for each entry. The first line should be flush with the left margin, while any lines that follow should be indented five spaces. (Hanging indentation is the opposite of normal indenting rules for paragraphs.)

List entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. For a work with multiple authors, use the last name of the first author listed.

List authors’ names using this format: Smith, J. C.

For a work with no individual author(s), use the name of the organization that published the work or, if this is unavailable, the title of the work in place of the author’s name.

For works with multiple authors, follow these guidelines:

- For works with up to and including seven authors, list the last name and initials for each author.

- For works with more than seven authors, list the first six names, followed by ellipses, and then the name of the last author listed.

- Use an ampersand before the name of the last author listed.

Use title case for journal titles. Capitalize all important words in the title.

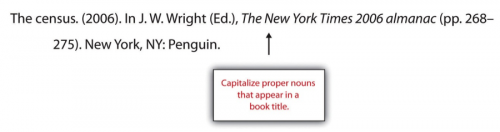

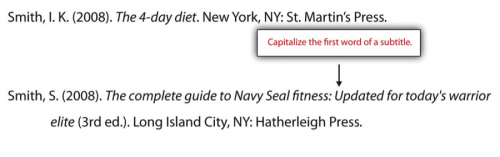

Use sentence case for all other titles—books, articles, web pages, and other source titles. Capitalize the first word of the title. Do not capitalize any other words in the title except for the following:

- Proper nouns

- First word of a subtitle

- First word after a colon or dash

Use italics for book and journal titles. Do not use italics, underlining, or quotation marks for titles of shorter works, such as articles.

Tip

There are many word processing programs and websites available that allow you to just plug in your referencing information and it will format it to the style required. If you decide to use such a program, you must still check all your references against your referencing guide because the way those programs and sites piece the information together may not be the exact way you are expected to do so at your school. Always double check!

Writing at Work

Citing other people’s work appropriately is just as important in the workplace as it is in school. If you need to consult outside sources to research a document you are creating, follow the general guidelines already discussed, as well as any industry-specific citation guidelines. For more extensive use of others’ work—for instance, requesting permission to link to another company’s website on your own corporate website—always follow your employer’s established procedures.

Formatting Reference Page Entries

As is the case for in-text citations, formatting reference entries becomes more complicated when you are citing a source with multiple authors, various types of online media, or sources for which you must provide additional information beyond the basics listed in the general guidelines. The following sections show how to format reference entries by type of source.

Print Sources: Books

For book-length sources and shorter works that appear in a book, follow the guidelines that best describe your source.

A Book by Two or More Authors

List the authors’ names in the order they appear on the book’s title page. Use an ampersand (&) before the last author’s name.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

An Edited Book with No Author

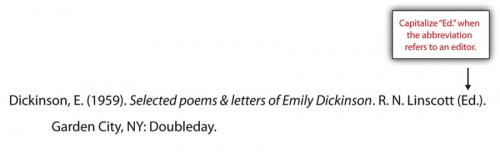

List the editor or editors’ names in place of the author’s name, followed by Ed. orEds. in parentheses.

Myers, C., & Reamer, D. (Eds.). (2009). 2009 nutrition index. San Francisco, CA: HealthSource, Inc.

An Edited Book with an Author

List the author’s name first, followed by the title and the editor or editors. Note that when the editor is listed after the title, you list the initials before the last name.

Tip

The previous example shows the format used for an edited book with one author—for instance, a collection of a famous person’s letters that has been edited. This is different from an anthology, which is a collection of articles or essays by different authors. For citing works in anthologies, see the guidelines later in this section.

A Translated Book

Include the translator’s name after the title, and at the end of the citation, list the date the original work was published. Note that for the translator’s name, you list the initials before the last name.

Freud, S. (1965). New introductory lectures on psycho-analysis (J. Strachey, Trans.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton. (Original work published 1933).

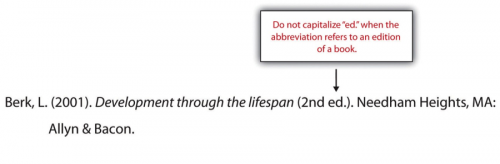

A Book Published in Multiple Editions

If you are using any edition other than the first, include the edition number in parentheses after the title.

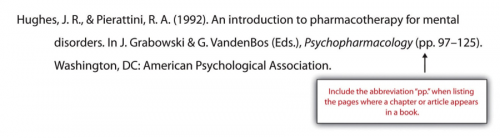

A Chapter in an Edited Book

List the name of the author(s) who wrote the chapter, followed by the chapter title. Then list the names of the book editor(s) and the title of the book, followed by the page numbers for the chapter and the usual information about the book’s publisher.

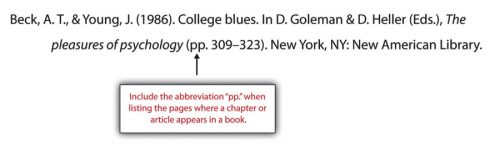

A Work That Appears in an Anthology

Follow the same process you would use to cite a book chapter, substituting the article or essay title for the chapter title.

An Article in a Reference Book

List the author’s name if available; if no author is listed, provide the title of the entry where the author’s name would normally be listed. If the book lists the name of the editor(s), include it in your citation. Indicate the volume number (if applicable) and page numbers in parentheses after the article title.

Two or More Books by the Same Author

List the entries in order of their publication year, beginning with the work published first.

Swedan, N. (2001). Women’s sports medicine and rehabilitation. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers.

Swedan, N. (2003). The active woman’s health and fitness handbook. New York, NY: Perigee.

If two books have multiple authors, and the first author is the same but the others are different, alphabetize by the second author’s last name (or the third or fourth, if necessary).

Carroll, D., & Aaronson, F. (2008). Managing type II diabetes. Chicago, IL: Southwick Press.

Carroll, D., & Zuckerman, N. (2008). Gestational diabetes. Chicago, IL: Southwick Press.

Books by Different Authors with the Same Last Name

Alphabetize entries by the authors’ first initial.

A Book Authored by an Organization

Treat the organization name as you would an author’s name. For the purposes of alphabetizing, ignore words like the in the organization’s name (e.g., a book published by the American Heart Association would be listed with other entries whose authors’ names begin with A.)

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV (4th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

A Book Authored by a Government Agency

Treat these as you would a book published by a non-governmental organization, but be aware that these works may have an identification number listed. If so, include the number in parentheses after the publication year.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). The decennial censuses from 1790 to 2000(Publication No. POL/02-MA). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Offices.

Print Sources: Periodicals

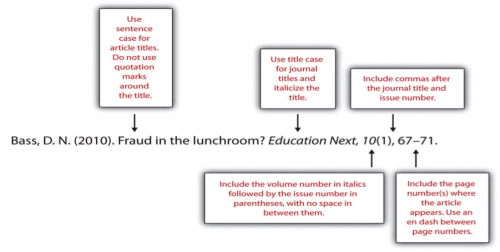

An Article in a Scholarly Journal

Include the following information:

Author or authors’ names

Publication year

Article title (in sentence case, without quotation marks or italics)

Journal title (in title case and in italics)

Volume number (in italics)

Issue number (in parentheses)

Page number(s) where the article appears

DeMarco, R. F. (2010). Palliative care and African American women living with HIV. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(5), 1–4.

An Article in a Journal Paginated by Volume

In journals, page numbers are continuous across all the issues in a particular volume. For instance, the winter issue may begin with page 1, and in the spring issue that follows, the page numbers pick up where the previous issue left off. (If you have ever wondered why a print journal did not begin on page 1, or wondered why the page numbers of a journal extend into four digits, this is why.) Omit the issue number from your reference entry.

Wagner, J. (2009). Rethinking school lunches: A review of recent literature. American School Nurses’ Journal, 47, 1123–1127.

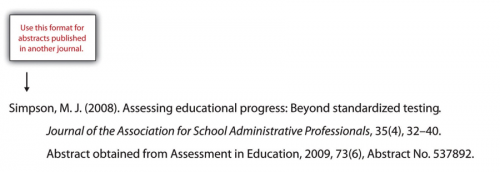

An Abstract of a Scholarly Article

At times you may need to cite an abstract—the summary that appears at the beginning of a published article. If you are citing the abstract only, and it was published separately from the article, provide the following information:

Publication information for the article

Information about where the abstract was published (for instance, another journal or a collection of abstracts)

A Journal Article with Two to Seven Authors

List all the authors’ names in the order they appear in the article. Use an ampersand before the last name listed.

Barker, E. T., & Bornstein, M. H. (2010). Global self-esteem, appearance satisfaction, and self-reported dieting in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(2), 205–224.

Tremblay, M. S., Shields, M., Laviolette, M., Craig, C. L., Janssen, I., & Gorber, S. C. (2010). Fitness of Canadian children and youth: Results from the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Reports, 21(1), 7–20.

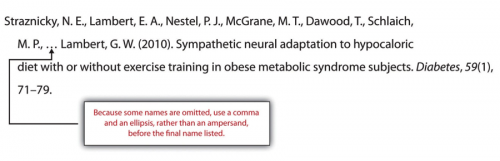

A Journal Article with More Than EightAuthors

List the first six authors’ names, followed by a comma, an ellipsis, and the name of the last author listed. The article in the following example has 16 listed authors; the reference entry lists the first six authors and the 16th, omitting the seventh through the 15th.

Writing at Work

The idea of an eight-page article with 16 authors may seem strange to you—especially if you are in the midst of writing a 10-page research paper on your own. More often than not, articles in scholarly journals list multiple authors. Sometimes, the authors actually did collaborate on writing and editing the published article. In other instances, some of the authors listed may have contributed to the research in some way while being only minimally involved in the process of writing the article. Whenever you collaborate with colleagues to produce a written product, follow your profession’s conventions for giving everyone proper credit for their contribution.

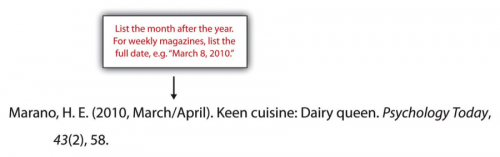

A Magazine Article

After the publication year, list the issue date. Otherwise, magazine articles as you would journal articles. List the volume and issue number if both are available.

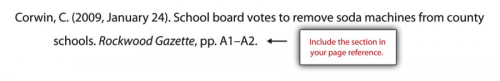

A Newspaper Article

Treat newspaper articles as you would magazine and journal articles, with one important difference: precede the page number(s) with the abbreviation p. (for a single-page article) or pp. (for a multipage-page article). For articles that have non-continuous pagination, list all the pages included in the article. For example, an article that begins on page A1 and continues on pages A4 would have the page reference A1, A4. An article that begins on page A1 and continues on pages A4 and A5 would have the page reference A1, A4–A5.

A Letter to the Editor

After the title, indicate in brackets that the work is a letter to the editor.

Jones, J. (2009, January 31). Food police in our schools [Letter to the editor]. Rockwood Gazette, p. A8.

A Review

After the title, indicate in brackets that the work is a review and state the name of the work being reviewed. (Note that even if the title of the review is the same as the title of the book being reviewed, as in the following example, you should treat it as an article title. Do not italicize it.)

Electronic Sources

Citing Articles from Online Periodicals: URLs and Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs)

Whenever you cite online sources, it is important to provide the most up-to-date information available to help readers locate the source. In some cases, this means providing an article’s URL, or web address. (The letters URL stand for uniform resource locator.) Always provide the most complete URL possible. Provide a link to the specific article used, rather than a link to the publication’s homepage.

As you likely know, web addresses are not always stable. If a website is updated or reorganized, the article you accessed in April may move to a different location in May. The URL you provided may become a dead link. For this reason, many online periodicals, especially scholarly publications, now rely on DOIs rather than URLs to keep track of articles.

A DOI is a digital object identifier—an identification code provided for some online documents, typically articles in scholarly journals. Like a URL, its purpose is to help readers locate an article. However, a DOI is more stable than a URL, so it makes sense to include it in your reference entry when possible. Follow these guidelines:

If you are citing an online article with a DOI, list the DOI at the end of the reference entry.

If the article appears in print as well as online, you do not need to provide the URL. However, include the words electronic version after the title in brackets.

In all other respects, treat the article as you would a print article. Include the volume number and issue number if available. (Note, however, that these may not be available for some online periodicals.)

An Article from an Online Periodical with a DOI

List the DOI if one is provided. There is no need to include the URL if you have listed the DOI.

Bell, J. R. (2006). Low-carb beats low-fat diet for early losses but not long term. OBGYN News, 41(12), 32. doi:10.1016/S0029-7437(06)71905-X

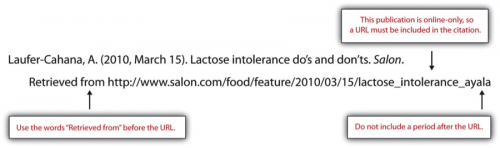

An Article from an Online Periodical with No DOI

List the URL. Include the volume and issue number for the periodical if this information is available. (For some online periodicals, it may not be.)

Note that if the article appears in a print version of the publication, you do not need to list the URL, but do indicate that you accessed the electronic version.

Robbins, K. (2010, March/April). Nature’s bounty: A heady feast [Electronic version]. Psychology Today, 43(2), 58.

A Newspaper Article

Provide the URL of the article.

McNeil, D. G. (2010, May 3). Maternal health: A new study challenges benefits of vitamin A for women and babies. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/04/health/04glob.html?ref=health

An Article Accessed through a Database

Cite articles accessed through a database the same way you would normally cite a print article. Provide database information only if the article is difficult to locate.

Tip

APA style does not require the item number or accession number for articles retrieved from databases. You may choose to include it if the article is difficult to locate or the database is an obscure one. Check with your instructor for specific requirements for your course.

An Abstract of an Article

Format article abstracts as you would an article citation, but add the word Abstract in brackets after the title.

Bradley, U., Spence, M., Courtney, C. H., McKinley, M. C., Ennis, C. N., McCance, D. R.…Hunter, S. J. (2009). Low-fat versus low-carbohydrate weight reduction diets: Effects on weight loss, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular risk: A randomized control trial [Abstract]. Diabetes,58(12), 2741–2748. http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/early/2009/08/23/db00098.abstract

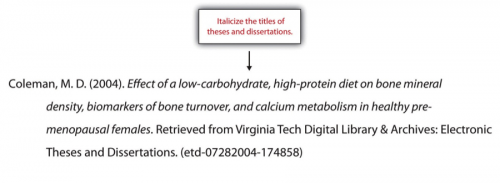

A Nonperiodical Web Document

The ways you cite different nonperiodical web documents may vary slightly from source to source, depending on the information available. In your citation, include as much of the following information as you can:

Name of the author(s), whether an individual or organization

Date of publication (Use n.d. if no date is available.)

Title of the document

Address where you retrieved the document

If the document consists of more than one web page within the site, link to the homepage or the entry page for the document.

American Heart Association. (2010). Heart attack, stroke, and cardiac arrest warning signs. Retrieved from http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3053

An Entry from an Online Encyclopedia or Dictionary

Because these sources often do not include authors’ names, you may list the title of the entry at the beginning of the citation. Provide the URL for the specific entry.